Research has shown that creating a more educated work force by increasing college completion can both improve the economy and help more people enter the middle class. But a substantial increase in national completion rates will likely be expensive.

A new paper from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences seeks to determine when the economic benefits to individuals and the national economy of such a completion boost would begin to outweigh investment costs.

“The analysis shows that beginning in the 11th year of the program, the cost-benefit balance begins to turn around, and in every year thereafter output and earnings in the economy are higher than they would have been without the investment,” said Michael S. McPherson, who co-chairs the academy’s Commission on the Future of Undergraduate Education.

That bottom-line finding comes with plenty of caveats. The paper is based on a wide range of assumptions about wage and productivity gains. And questions remain about how best to boost completion at a large scale, the paper said, and how much those efforts would cost.

McPherson, an economist who is president emeritus of the Spencer Foundation and the former president of Macalester College, said “no precise or definitive answer to this question is possible.” However, he said, it was worthwhile to attempt a well-informed estimate of the costs and benefits of a “systematic program of investment in improved college completion.”

The paper is part of the broader commission’s work, which will include a final report on college quality, completion and affordability, which is slated for release in late November.

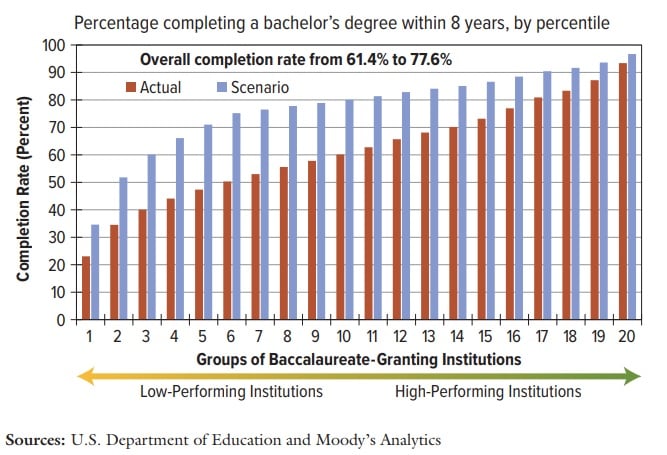

For this study, the commission partnered with Moody’s Analytics, an economic consulting and forecasting firm. Moody’s compared a baseline model, where recent trends in college completion and degree production continue, with a scenario where completion rates increase significantly.

Currently, at four-year institutions, just 60 percent of first-time, full-time college students earn a bachelor’s degree, the paper said, with an average time to completion of six years. Likewise, 30 percent of students who enroll in a certificate or associate-degree program earn a credential within three years.

The economic benefits of attending college tend to require getting to graduation. And students who drop out with even relatively small amounts of debt face a substantial risk of default, previous research has found.

Some institutions have been successful in improving completion rates. And lessons learned by those colleges became part of the college completion push led by the Obama administration, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Lumina Foundation.

As examples, the new paper cites programs from Georgia State University and the City University of New York, which feature scholarship funding, transportation assistance and having trained advisers monitor student progress and intervene when necessary.

With these and other investments applied nationwide, the study assumes a gradual increase in completion rates over a 10-year period. Colleges with a completion rate under 50 percent increase their rates by half, the paper assumes, while those with completion rates over 50 percent see noncompletion decreasing by half.

Big Gains, Big Investments

The baseline model estimates that the proportion of the U.S. population with a bachelor’s degree will rise from 31 percent in 2016 to 40 percent in 2046. Under the higher-completion scenario, 46 percent of Americans would hold a bachelor’s degree by 2046.

The share of Americans with an associate degree would rise to 15 percent from 10 percent currently, compared to 12 percent for the baseline estimate.

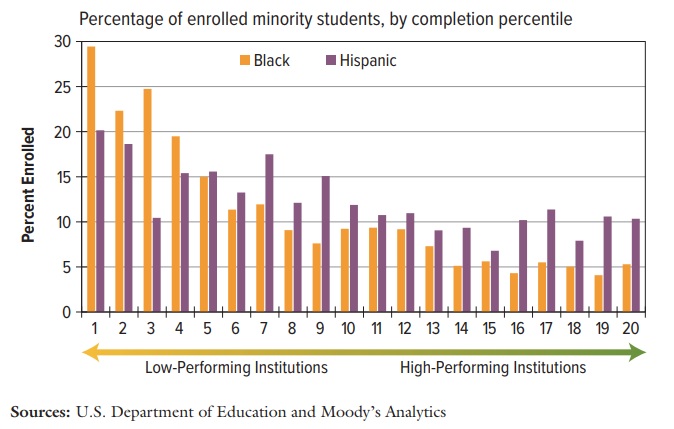

Benefits of such an increase would be particularly important for students from low-income backgrounds and minority groups, the paper said, as they disproportionately attend colleges with low completion rates.

In addition, McPherson took on the increasingly common argument that too many students are attending college.

“Some people claim that we are already educating nearly everybody who can benefit,” he wrote, “but that claim is dubious in light of the fact that a number of other countries now have a larger fraction of their younger cohorts completing college than the United States does.”

Even so, a moon-shot style investment in getting many more students to graduation comes with an estimated price tag that would make NASA blush.

“While schools and colleges, even as they make these investments, may be able to save money in other ways, perhaps through technology or cutting back on lower-priority programs,” said McPherson, “it would be wishful thinking to assume that we can substantially improve educational success for disadvantaged students without investing money in the effort.”

Direct costs for completion programs during the first decade of such a project would come from both private and public sources. And with dropout rates down, more students would be in college and out of the work force, while older students would leave jobs to invest in going to college. Those indirect costs also would put a drag on the economy, the paper said.

As for government spending, the analysis assumes that additional completion funding would be financed by debt rather than tax hikes. The estimated greater spending on higher education would result in a peak impact on the federal deficit of $138 billion in 2025. The increase in U.S. debt related to the effort would peak at $1.9 trillion in 2041.

However, the effect on the deficit would begin to decline in 2026, due to employment and wage gains, and eventually be lower than the estimated baseline deficit. The debt impact also would decline to $1.6 trillion by 2046, an increase of 2.6 percent compared to the baseline. (A lower-cost model found less impact on deficits and debt.)

“Increased earnings and productivity will expand the economy in the long run, translating to higher wages, employment and gross domestic product,” the report said. “However, using illustrative estimates of the likely costs, the net effect on the federal government deficit will be negative for some time.”

Average earnings would increase by 3.1 percent under the higher-college-completion model, according to the paper, while employment would increase by 0.5 percent. Likewise, total real GDP would be 2.5 percent larger than under the baseline.

McPherson compares the long-term impact of an ambitious completion push to physical infrastructure investments like the federal government’s creation of the Interstate Highway System in the 1950s and 1960s. That project also came with big costs, disruptions and dislocations.

Over time, however, the speed and reliability of highway travel and commerce yielded economic benefits that far outweigh the costs.

“We can expect to see the same pattern again should we embark on new infrastructure programs like repairing the nation’s bridges, improving urban transit systems or combating global warming through developing cleaner energy sources,” McPherson said. “And education investments are among the longest lasting in economic terms. A student taking a few years out of the work force to earn a degree will typically receive an earnings benefit (and the economy will receive a productivity boost) that will continue for 30 or 40 years -- longer than most bridges or highways last.”