The Ghost Budget: U.S. War Spending & Fiscal Transparency

Most experts maintain that oversight, including ex post oversight, is critical to ensure that government actions are transparent and accountable to its citizens. But despite a global push for greater transparency in government, the level of transparency over national security and public spending in many countries is limited. This essay shows that since 9/11, the conduct of the United States in the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the wider region has diminished oversight over military spending by funding operations with “emergency” appropriations and other special budgetary vehicles, financing with debt, concealing expenses through poor accounting, and integrating the private sector into core military activities. This combination of policies, which I term the Ghost Budget, has resulted in less accountability for war spending, lower civic engagement, greater corruption, higher total expenditures, and prolonged conflicts.

In recent decades, the push for government transparency, championed by entities such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and United Nations, has gained significant global momentum. Transparency, defined as “enabling public insight into government operations,” is now supported by Right to Information (RTI) laws in more than 130 countries, up from nineteen countries three decades ago.1 Advocates link transparency to increased civic engagement, enhanced accountability, and reduced corruption.2 In democratic societies, transparency is seen as a citizen’s right, foundational to government accountability and civic participation.3

The role of transparency in governance traces back to the Enlightenment. Sir Francis Bacon wrote in 1597 that ipsa scientia potestas est (“knowledge itself is power”).4 The concept is also linked to better human behavior. For example, Jeremy Bentham argued that “the more strictly we are watched the better we behave.”5 Bentham specifically connected transparency to fiscal disclosure, urging that public accounts and fees should be published and open to general view.

The belief that transparency influences how we act forms the basis for much of the legal, regulatory, and governmental structure of modern societies. American presidents routinely pay homage to the idea that transparency, including in fiscal policy, is necessary to hold governments accountable.6 America’s founders wrote the U.S. Constitution during the same period Bentham was exploring these ideas. They codified the notion that citizens are entitled to know what their government is doing (in most cases), and that they need to know it to ensure that the government acts in the public interest. As James Madison famously inscribed, “A popular government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but prologue to a farce or a tragedy; or perhaps both. . . . A people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.”7

There are two major obstacles to this lofty ideal. The first is limitations in national security. Even the staunchest supporters of transparency admit that there may be limits to transparency when national security is at stake. The second obstacle is that most governments provide less transparency on spending and budgets than in any other area. For example, over half of the countries with RTI laws fail to meet basic budget transparency standards.8 Since one of the largest expenditures—in many countries, the single largest expenditure—in the budget is national security (including defense, military activity, intelligence gathering, and veterans spending), the lack of fiscal transparency over national security spending makes it one of the government functions least accountable to the public.

The secrecy dilemma is that government decisions about national security require the fullest transparency so the public can hold government accountable, yet, at the same time, even minor disclosures of such information may pose risks to national security.9 The “mosaic theory,” for example, holds that disparate pieces of information may be significant if combined with other pieces of information, even if they have no value individually.10

This dilemma has often been debated, including in the aftermath of Watergate, Vietnam, and the Cold War, as well as during the post-9/11 environment and the “global war on terror.”11 Some have argued that national security outranks transparency in the interest of protecting the public.12 Others believe that withholding too much information impairs national security. For example, political scientist Harold Lasswell avows that “overzealousness” in support of national defense weakens national security, in part because withholding key information from the public will “dry up” informed public opinion and weaken Congress’s ability to control the executive.13

Secrecy can also lead to mistakes. Daniel Patrick Moynihan argued that excessive secrecy and overclassification of national security data led to some of the worst mistakes during Vietnam and the Cold War.14 Governance scholar Alasdair Roberts has written that “fatigue, confusion and ignorance about key facts” led to a series of missteps in Vietnam, for which America paid an “incalculable price.”15 Economist Joseph Stiglitz and I, as well as the 9/11 Commission and others, have posited that justification for the Iraq War was based on flawed information whose secrecy compounded the analytical weaknesses of the intelligence services.16

Fiscal transparency refers to openness in budgetary and spending practices that enables citizens to track how public funds are used. Apart from the national security arena, most governments agree that “open budget” practices are desirable and can reduce waste and corruption and improve government efficiency.17

Nevertheless, there are several factors that restrict the flow of information on budgets and fiscal matters. First, there is a difference between “nominal” and “effective” transparency.18 Nominal transparency includes things like scoring on indices or enacting RTI laws, while effective transparency entails genuine access to comprehensible fiscal information.

Economists George Akerlof, George Stigler, Andrew Weiss, and Joseph Stiglitz, among others, have shown that in order for technical information (such as financial accounts, budgets, and fiscal projections) to be fully transparent, there needs to be a knowledgeable audience to receive and interpret it.19 If the government does not provide data in a way that recipients can understand, or if the price of securing the information is too high, then the government will likely not achieve the benefits of transparency, including civic engagement and accountability.20

There are also distinctions between different types of secrets, such as “deep” versus “shallow” secrets. A shallow secret might be knowing that your boss is holding a meeting about you without knowing what is being said, while a deep secret would be not knowing the meeting is happening at all. Former U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld captured this idea in his famous remark: “There are known knowns—things we know we know. There are known unknowns—things we know we don’t know. And there are unknown unknowns—things we don’t know we don’t know.”21

There is also a key difference between information produced in the private sector and that produced in the public sector. In private business, financial information is typically proprietary, and private government contractors operate under different regulatory and incentive structures than public entities. By contrast, information collected by the government and funded by taxpayers should rightly belong to the public.22 This poses a challenge to fiscal accountability for U.S. defense spending, of which some 50 percent goes to private contractors.23 And although the United States has “freedom of information” laws (in particular, the Freedom of Information Act), contractors can avoid financial disclosure by claiming they are protecting their trade secrets.24

The World Bank, the IMF, and other organizations have produced a copious amount of material on fiscal transparency related to budget preparation, audits, report reliability, and integrity. They maintain that “effective” fiscal transparency has five requirements: robust financial reporting and accounting, timely public dissemination, rigorous monitoring, alignment of budgetary and fiscal reports, and an overall open process.25 Accountancy scholar David Heald has further distinguished between “intrinsic” barriers (such as poor accounting and technical complexity) and “constructed” barriers (including off-budget funding and future unaccounted expenses).26

Applying this model to U.S. fiscal transparency during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars reveals deficiencies in each area. Throughout the two decades of these conflicts, the U.S. government failed to account fully for war-related expenses. Information was restricted both on military matters—such as casualty data and records of injuries and medical evacuations, which remained classified for much of the war—and on expenditures, particularly those related to defense contractors, due to a lack of transparency.

Oversight is often identified as the solution to the secrecy dilemma—particularly over wartime finance. Many scholars have highlighted that if the public has a right to know about military operations, then oversight, either concurrent or ex post (such as audits, legislative reviews, program evaluations, reports, investigations, and commissions), is essential.27 Thus, if real-time oversight is not being conducted, it is critical to produce data that will permit retrospective oversight.28

On paper, the United States has a robust set of institutions that are equipped to perform oversight. The Constitution gives Congress the “power of the purse.” It has final discretion over public spending and controls legislative hearings, the budget, and evaluation agencies (like the Congressional Research Service and Congressional Budget Office) and audit agencies (such as the Government Accountability Office [GAO]). It also has access to the executive agencies, to inspectors general and quasigovernmental entities, and to think tanks, media, and civil society organizations. After 9/11, the United States also set up special oversight bodies, including the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan and the Special Inspector General for Iraq (SIGIR) and Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR).

Despite this vast framework of “nominal transparency,” the nation largely failed to track and account for the costs of the post-9/11 Iraq and Afghanistan wars, which together were likely the most expensive conflicts in U.S. history.29 The budgetary gimmicks used to appropriate funds for the wars, the financing methods used to pay for them, and the conduct of the wars themselves all limited oversight and illustrate the consequences when there is little accountability.

The United States employed four mechanisms that had the effect of restricting fiscal oversight throughout and after the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: 1) funding the conflict entirely through debt, 2) using emergency supplemental and other special vehicle budget mechanisms, 3) poor accounting, and 4) excessive use of private-sector contractors. These mechanisms collectively hindered the availability, accuracy, and auditability of wartime financial data, undermining accountability structures necessary for public oversight.

Prior to the twenty-first century wars on terror, the United States financed every major conflict through a combination of tax increases, cuts to nonwar funding, and limited borrowing (see Table 1). The government appealed to the public directly, using presidential speeches, memoranda, and other communications to justify such measures. During World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to paying higher taxes for the war as a “privilege.”30 President Harry Truman, while raising top marginal tax rates to 92 percent, gave more than two hundred speeches calling for a “pay as we go” approach to financing the Korean war.31

We could try to escape the financial cost of defense by borrowing—but that would only transfer the financial problem to our children, and would increase the danger of inflation with its grossly unfair distribution of the burden. The sensible and honest thing to do now is to tax ourselves enough, as we go along, to pay the financial costs of defense out of our current income.32

President Lyndon B. Johnson, who reluctantly imposed a tax surcharge to pay for the Vietnam War in order to stem inflation, told reporters that he had to figure “how to pay for these fucking wars and keep my commitment to feed, educate and care for the people of this country.”33

The post-9/11 funding pattern, however, was unprecedented in the history of U.S. military conflicts.34 For the first time since the American Revolutionary War, war costs were paid for almost entirely by debt. There were no wartime tax increases or cuts in spending. Quite the reverse: far from demanding sacrifices, President George W. Bush slashed federal taxes in 2001 and again in 2003, just as the United States invaded Iraq; President Donald Trump reduced taxes further in 2017.

| War of 1812 | Civil War | Spanish-American War | WWI | WWII | Korean War | Vietnam War | Gulf War | Post-9/11 Wars | |

| Tax Increases | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Non-War Budget Cuts | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Source: Table from Linda J. Bilmes, “The ‘Ghost Budget’: Explaining U.S. Budgetary Deviations during the Post-9/11 Wars” (PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2020). | |||||||||

The decision to finance the wars with debt reduced congressional oversight on war spending. During prior wars, the Senate and House fiscal committees, which control tax policy in the country, were obligated to hold hearings on the financing of the wars because Congress is required to approve any tax increases. These committees were forced to address the issue of how to pay for the wars. Comparing the hearings of the committees in charge of tax policy (the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee) from the Korea, Vietnam, and post-9/11 periods, it is evident that these committees devoted far less time to evaluating the cost of the post-9/11 wars than they had during previous wars (see Table 2).35

| Korea (1950–1953) | Vietnam (1965–1973) | Post-9/11 (2001–2018) | ||

| Senate Finance Committee | Total Hearings | 55 | 134 | 681 |

| Relevant Hearings * | 9 | 10 | 20 | |

| Mentions | 5 | 7 | 1 | |

| Percent Mentioned | 56 | 70 | 5 | |

| House Ways & Means Committee | Total Hearings | 49 | 200 | 612 |

| Relevant Hearings * | 7 | 19 | 47 | |

| Mentions | 5 | 14 | 7 | |

| Percent Mentioned | 71 | 74 | 15 | |

* Excludes hearings on topics such as trade agreements, tariffs, customs duties, banking, bonded debt, Social Security, and confirmation of appointees. Source: Table from Linda J. Bilmes, “The ‘Ghost Budget’: Explaining U.S. Budgetary Deviations during the Post-9/11 Wars” (PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2020). | ||||

Congress was not required to discuss and approve painful tax increases that would have signaled the snowballing cost to the public. Rather, the financial cost of the conflicts was deferred to future generations through increasing government borrowing. Overall, federal taxes declined from 18.8 percent of GDP in 2001 to 16.2 percent by the start of 2020. In the same period, outstanding federal debt held by the public rose from $3.5 trillion to more than $20 trillion.36

The absence of tax increases also changed how the public viewed the expense of the conflict. As political scientist Sarah Kreps has proved, the public experiences debt differently from paying taxes. Taxes are painful, so people pay attention to higher taxes. The public is more attentive to the costs and the duration of a conflict if it is financed through taxation. Kreps argues that debt financing severs this relationship, since the public no longer associates the value of war with the level of taxation.37

Not only was the debt-financing strategy unprecedented, but the budgetary mechanism used to approve the vast post-9/11 wartime spending also diverged radically from the past. In previous conflicts, the United States paid for wars as part of its regular defense appropriations (the defense “base budget”), after the initial period (one to two years) of supplemental funding bills.

By contrast, the United States paid for the first decade of its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, from FY 2001 to FY 2011, using “emergency supplemental appropriations.” “Emergency funding” refers to the practice of allocating resources outside of the regular budget cycle and vetting processes, ostensibly to deal with unexpected emergencies such as natural disasters.38 Such emergency spending measures are exempt from regular vetting and procedural rules in Congress because the intent is to disburse money quickly when delay would be harmful. However, the regulatory guidelines for what qualifies for the “emergency” designation are vague. In the United States, such spending is supposed to meet five criteria: a need that is “necessary, sudden, urgent, unforeseen, and not permanent.”39 There is no mechanism to determine whether a particular item meets these criteria, which means that effectively anything may be labeled as “emergency.”

Congress continued to enact “emergency supplemental appropriations” even as the war effort expanded. In 2003, the United States sent 130,000 military personnel to Iraq (alongside troops from coalition countries). By 2009, the United States had 187,200 U.S. “boots on the ground” in Iraq and Afghanistan, plus a similar number of military contractors, with nearly five hundred U.S. military bases set up across Iraq, yet the conflict was still being paid for as a temporary, unforeseen “emergency.”40

Emergency spending also takes the form of “special spending” categories. In FY 2012, President Barack Obama shifted from using emergency supplemental funding to a newly designated special category called Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). The OCO category was designed explicitly to be exempt from regular congressional spending limits and direct oversight.

Between 2001 and 2021, Congress enacted more than $2 trillion in direct appropriations for the wars, all but two of which were designated as “emergency” or OCO.41 This approach minimized congressional scrutiny and discouraged detailed tracking of war-related costs. The House and Senate appropriations committees were not required to make trade-offs between war spending and regular spending; consequently, they too held fewer hearings on these topics. Comparing the number of hearings at which these topics were discussed during the Korean, Vietnam, and post-9/11 war years, the decrease in oversight is apparent (see Table 3).

| Korea (1950–1953) | Vietnam (1965–1973) | Post-9/11 (2001–2018) | ||

| Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense | Total Relevant Hearings * | 17 | 53 | 29 |

| Mentions | 6 | 42 | 5 | |

| Percent Mentioned | 35 | 79 | 17 | |

| House Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense | Total Relevant Hearings * | 10 | 65 | 39 |

| Mentions | 8 | 35 | 3 | |

| Percent Mentioned | 80 | 54 | 15 | |

* Reflects data-mining of all hearings in the three periods. Excludes hearings regarding individual topics, such as specific line items (military construction items, naming of ships, specific contracts, service requests, items unrelated to the post-9/11 wars, and so on). Source: Table from Linda J. Bilmes, “The ‘Ghost Budget’: Explaining U.S. Budgetary Deviations during the Post-9/11 Wars” (PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2020). | ||||

Over time, the Pentagon grew accustomed to receiving a steady stream of war funding that bypassed the department’s regular internal budget prioritization system, which is part of the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) process that allocates resources to support the department’s missions. Some two-thirds of OCO funds went into the Pentagon’s Operations & Maintenance (O&M) account compared with only one-third of the funds from the regular defense appropriations going into that account. This gave DOD far greater discretion, since O&M is the most flexible account and can be used for a wide range of purposes, including payments to private contractors. The emergency/OCO vehicle also became a convenient way for Congress and the military to avoid making offsetting cuts elsewhere in the budget. And the Pentagon used Iraq and Afghanistan OCO funds to cover unrelated expenses, including more than $25 billion for the “European Reassurance Initiative,” which funded a military buildup in Europe and Ukraine following Russia’s 2014 takeover of Crimea.42

Labeling nonurgent spending as emergencies had several political advantages. It enabled lawmakers to circumvent congressional political and budgetary dysfunction that may have delayed regular budget appropriations. It also enabled the Bush, Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations to avoid spending caps, to minimize future deficit projections, and to maintain the illusion that funding was temporary. However, emergency spending has multiple drawbacks. Due to the vagueness of the category and lack of defined reporting requirements, it decreases transparency and increases overall spending, with serious consequences for budget integrity.

This Ghost Budget made it effectively impossible to measure the total costs of the wars: estimates have ranged from $1.8 trillion to more than $8 trillion. The one constant among those who have attempted to tally it up is that no one really knows.43 This uncertainty fit neatly with successive governments’ desire to obscure rising war costs from an increasingly skeptical electorate.

Formal accounting such as year-end audits and financial reporting are critical forms of ex post oversight. During the post-9/11 wars and subsequently, the United States has notably failed to ensure such accountability.

First, the emergency supplemental process reduced the requirements for information during the budget formulation and justification stages. At some points, nearly one-quarter of the total defense budget was going to the war, yet the Pentagon provided no pages of budget justification (see Table 4). This lack of upfront information made it difficult for the regular oversight agents to understand costs; for example, eight years into the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) reported that even taking into account “known factors” such as operating tempo of the war, the size of the troop force, and the use of equipment and weapons, “none of these factors appear to be enough to explain the size of and continuation in increases in cost.”44

| Budget Year | Total # of Pages of DOD Budget Submission | # of Pages on OCO War Budget | % of Pages on OCO War Budget | Estimated % of U.S. Military Budget for OCO |

| FY 2005 | 227 | 3 | 1.3 | 15.8 |

| FY 2010 | 209 | 0 | 0 | 23.5 |

| FY 2015 | 275 | 14 | 5.0 | 11.2 |

| FY 2019 | 109 | 8 | 7.3 | 10 |

Source: Table from Linda J. Bilmes, “The ‘Ghost Budget’: Explaining U.S. Budgetary Deviations during the Post-9/11 Wars” (PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2020). For DOD budgets, see Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2005 (U.S. Department of Defense, 2004); Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2010 (U.S. Department of Defense, 2009); Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2015 (U.S. Department of Defense, 2013); and Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2019 (U.S. Department of Defense, 2018). | ||||

Second, the war budgets made no provision for the considerable future costs of the wars. During this period, the Pentagon significantly expanded programs, benefits, and eligibility rules for military personnel. For example, compensation and benefits were raised by 47 percent for Reservists and members of the National Guard from 2001 to 2006, primarily in the form of long-term deferred benefits.45 Other deferred spending included the authorization of $40 billion in concurrent military benefits, adjustments to Social Security Disability Insurance, and payments for contractor disability claims.46 Benefits for veterans were expanded and upgraded throughout the wars, including higher stipends, expanded medical and education entitlements, broader eligibility, and longer time limits for claiming such benefits. The present value of the disability and medical benefits already awarded but not yet paid out to the service members and their families from the FY 2001 to FY 2021 Iraq and Afghanistan operations is estimated to exceed $2.2 trillion, excluding benefits payable due to exposure to burn pits.47 U.S. financial statements, however, account for only a fraction of this total, and exclude accrued medical benefits entirely.48

Third, the financial reporting and accounting systems within the Defense Department are chronically weak. The Pentagon only began auditing its accounting systems in 2018; it was the last department to do so after Congress required the practice across all government agencies in 1990. It remains the only federal department that has never passed a comprehensive audit. The Defense Department can only account for less than 40 percent of its $3.5 trillion in assets and, according to the GAO, it has made almost no progress toward corrective improvements over the past six years. As the GAO points out, the system is so ineffective that a single cargo truck could be valued between $0 and $497,562 “depending on [the] valuation method used.”49

These accounting flaws have continued to thwart effective oversight of U.S. military operations, including funding to Ukraine and Israel from 2022 to 2024. For example, in 2022, the DOD identified $6.2 billion in “underspend” on munitions drawdown in U.S. inventories, which had the effect of “freeing up” an additional $6.2 billion for Ukraine.50 In July 2024, the Pentagon identified another $2 billion accounting “error,” in which it reportedly used “replacement value” instead of “depreciated value” to determine costs of Ukraine aid. This maneuver produced an unexpected $2 billion in extra munitions available for the United States to send to Ukraine.51 Regardless of the benefits of the outcome, the accounting system has been widely pilloried, including in the British satirical magazine Private Eye.52

The conduct of the war served to further obscure fiscal transparency in several ways. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were the first major U.S. conflicts fought entirely by a combination of an “all-volunteer” military force and large-scale reliance on private contractors. The percentage of Americans serving in the armed forces was smaller than at any time in U.S. history, apart from the brief peacetime era between World War I and II. Less than 1 percent of the adult U.S. population was deployed to the combat zones in Afghanistan and Iraq, with no threat of conscription for the remainder.

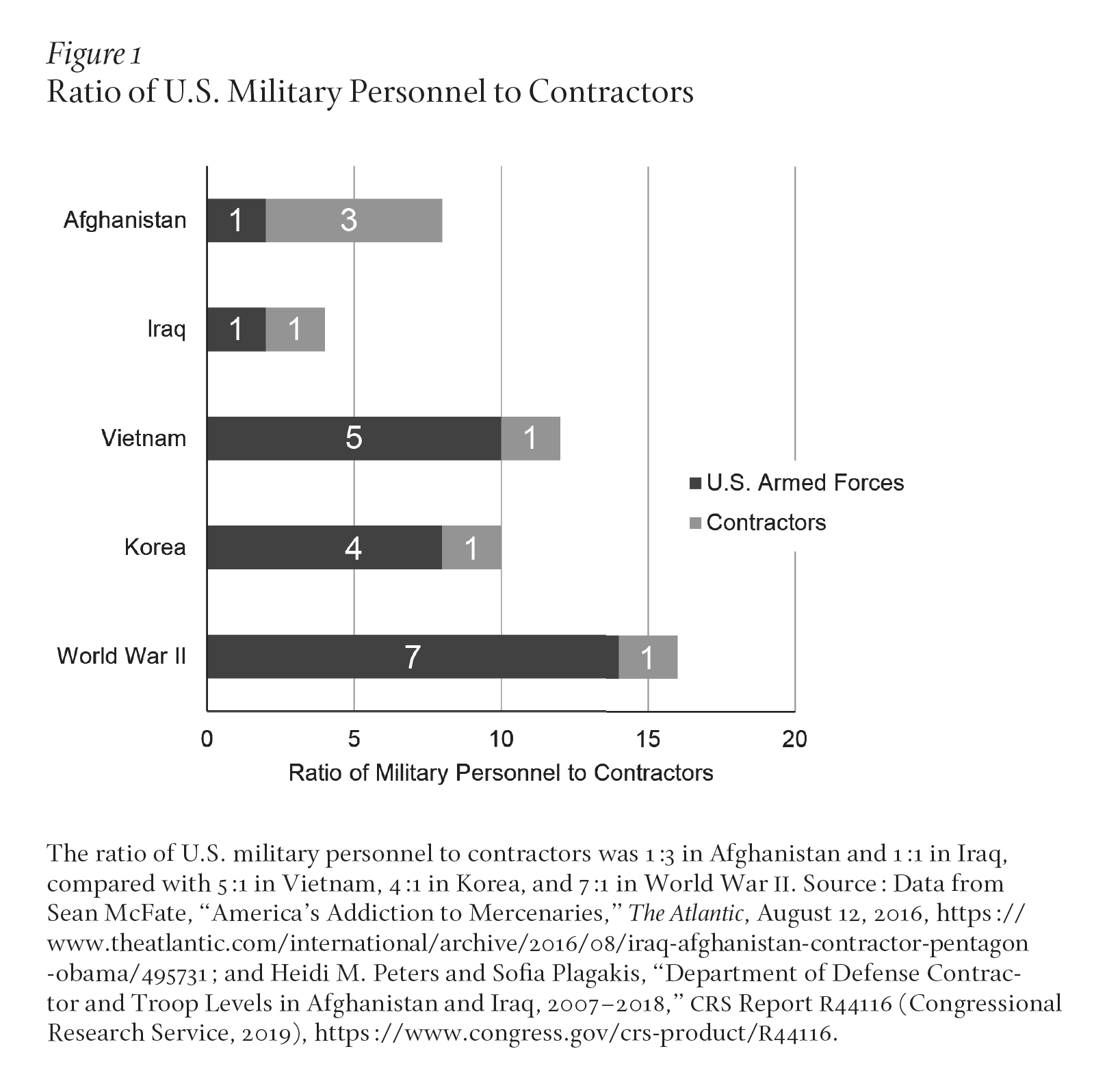

Virtually every activity and line item in the war appropriations included activities performed by private contractors. For the majority of two decades, the number of private contractors working in the Iraq and Afghanistan war zones exceeded the number of uniformed military troops (see Figure 1).

Under the umbrella of emergency spending, contracts were frequently awarded without a competitive tendering process, opening up opportunities for grift and corruption. Moreover, the disclosure rules that apply to private contractors are primarily focused on financial disclosures designed to protect their investors, rather than informing taxpayers at large. Consequently, tracking complex, long-term military projects and their associated risks is exceedingly difficult with a decentralized network of private contractors.53

For example, Senator James Webb, a member of the Commission on Wartime Contracting, remarked:

One of the eye-openers for me as a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was when we had testimony from the State Department discussing $32 billion of programs for Iraq reconstruction. As someone who spent time as a bean-counter in the Pentagon, I asked if they would provide us . . . a list of the contracts that had been let, the amounts of the contracts, a description of what the contracts were supposed to do, and what the results were. They could not provide us that list. For months we asked them. And they were unable to come up with a list of the contracts that had been let.54

Private contracting was subject to minimal scrutiny with respect to transparency and auditability. This opacity was compounded by vague reporting structures, contractor turnover, and insufficient access to performance metrics.

The public did not have to pay the financial costs of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in the form of higher taxes because of the historically unprecedented reliance on debt financing. Consequently, the cost of the wars was transferred to future generations. The ensuing public apathy enabled the president and Congress to continue funding the wars outside the existing budgetary process for two decades, neutering regular budgetary scrutiny and evading formal caps on overall government spending. Research provides support for such an outcome, showing that Americans are most interested in foreign policy when it has the greatest potential to affect them directly, and that public opinion can influence the level of military spending.55

This combination of reduced transparency and oversight yielded outcomes often predicted by transparency advocates: low public engagement, increased potential for corruption, and poor government accountability. Although the government may not have intended to hide the costs and information explicitly, the resultant opacity aligned the system more closely with secrecy, highlighting the tension between transparency ideals and practical governance during wartime. There was little public discussion or debate about trade-offs and allocation of scarce budgetary resources, as evidenced by the lack of attention to war spending by congressional committees and the almost complete absence of speeches by successive presidents on the cost of the conflicts.

The lack of oversight and transparency translated into large-scale profiteering and corruption. Private defense contractors in the United States experienced a huge surge in profits, as reflected in stock prices that outperformed the S&P 500 by more than 60 percent over the period.56 The Special Inspectors General appointed to report on spending in Iraq and Afghanistan cited numerous instances of profiteering, corruption, and “ghost” projects and personnel that did not in fact exist.

This case demonstrates that nominal oversight is not sufficient to ensure real accountability. Clear, accurate, and available data are critical to ensure transparency, but they were missing due to several major systemic failures. First, the disclosure system for private contractors was not designed to ensure public accountability. Contractors could in theory have been a mechanism for accountability if performance targets were clear and carefully structured. But the contractors themselves clearly preferred to avoid transparency, and the Pentagon, flush with emergency funding and in a rush to execute military operations, did not insist. Given the importance of contractors in these wars, this dynamic immediately created a serious oversight gap.

Second, chronically weak accounting systems at the Pentagon precluded any forensic ex post investigation of military spending. A clear audit trail, with standardized accounting principles, enables oversight bodies to “follow the money.” Such a capability is especially important for oversight of military spending given the cost and technological complexity of modern weapons systems. But in this case, it was almost totally absent.

Unfortunately, most of the elements of fiscal opacity discussed here have lived on beyond the military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan. The accounting deficiencies continue. Thus, for example, the Defense Department was able to “find” significantly more money for military assistance to Ukraine simply by redefining accounting valuations for its weapons inventory. Military assistance to Israel is subject to virtually no oversight and Israel is (uniquely) exempted from the requirement to subject its U.S. weapons purchases to congressional review.

Since 9/11, U.S. wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the broader region have reduced oversight of military spending. The Ghost Budget refers to the combination of policies that have led to less accountability, lower civic engagement, increased corruption, higher expenditures, and prolonged conflict.

The U.S. government failed to fully account for war-related expenses during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, restricting information on military matters and expenditures, particularly those involving defense contractors who were often awarded contracts without competitive tendering and with limited disclosure. War costs were financed almost entirely by debt, without the tax increases or spending cuts that accompanied all previous U.S. wars. The government used “emergency” supplemental appropriations and special categories like OCO to bypass regular budget processes and minimize scrutiny. Additionally, the Pentagon’s chronically weak financial reporting systems prevented even nominal oversight of military spending.

These practices diminished congressional oversight and hindered the government’s ability to evaluate war spending. Even as the United States withdrew from Afghanistan after two decades of war and occupation and reduced its military operations that involve boots on the ground, these entrenched practices continue to shape funding for military activities in theaters including Ukraine and the Middle East. This lack of transparency has not only eroded public engagement but also made it easier for the United States to remain locked in an endless cycle of war with little accountability.