How We Will Think about the Past in the Future?

How will we think about the past in the future? The central question for this Dædalus issue asks artists and scholars to speculate about what aspects of our present historical moment will enrapture, haunt, and/or plague thinkers in the future. The contributors–scientists, social scientists, humanists, and artists–conjure up the methodologies, theories, and scholarly and artistic practices we will need not only to rectify current harms, but also to usher in more equitable futures.

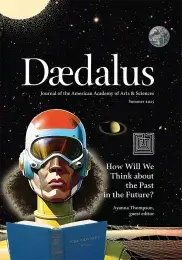

This edition of Dædalus looks very different. Altering a seventy-year tradition of text-only, monochromatic, or partially illustrated covers, this edition features a striking design by graphic designer Katie Burk that challenges us to imagine who or what will be looking to the past in the future.1 The jolt of that change is meant to provoke: Is that what your imagined future looks like? Is that how you see the future relating to the past? In many ways, this issue of Dædalus will surprise, shake, and jar the reader because it breaks with so many of the journal’s recent practices—in this issue, there are works of art, poetry, fiction, and drama interspersed among the academic essays, and everything is written from a speculative viewpoint. And yet, in just as many ways, this issue of Dædalus is deeply historical, returning to topics, themes, and approaches that have been explored in past volumes. For example, poetry and fiction were staples in Dædalus between 2001 and 2009, and speculative thinking was highlighted as far back as 1967, when an entire issue was dedicated to imagining a far distant future, “Toward the Year 2000.”2 This push and pull between exploring new and novel approaches and honoring past traditions rests at the heart of speculative thinking and creation.

As a Shakespeare scholar, I am all too familiar with the fact that how we think about the past frequently changes. Shakespeare, after all, played fast and loose with time and history in his plays. No matter when and where his plays were set—ancient Rome, medieval Denmark, Renaissance Venice—they seemed to be as much about contemporary, seventeenth-century England as anything else. In fact, the only extant drawing from a Shakespearean performance made during Shakespeare’s lifetime, the Longleat manuscript, also known as the Peacham drawing, makes it clear that the costumes for Shakespeare’s plays were time-tripping too. Despite the fact that the play depicted in the drawing, Titus Andronicus, ostensibly takes place in ancient Rome, the costumes seem an odd mixture of ancient Roman, early modern English, early modern Spanish, and medieval English styles. As Shakespeare scholar Jonathan Gil Harris has argued, time, for Shakespeare, was “untimely”: that is, “polychronic and multitemporal.”3 Shakespeare was the OG of time travel.

Moreover, our narratives about the historical, literary, and theatrical figure of William Shakespeare have changed with each new era. Shakespeare does not stay put in history; rather, he moves around like the “inconstant moon,” to borrow a line from his Juliet, reflecting back our light as his own.4 In the Restoration, for example, he was an artist whose works needed frequent improvement and rewriting—a flawed, working playwright according to Restoration authors like John Dryden. By the late eighteenth century, however, Shakespeare was viewed as almost godlike in his gifts as a creator; he was worshipped in the age of Bardolatry. How we think about the past is frequently a litmus test for what preoccupies us in the present. But how we imagine what should preoccupy us in the future offers the possibility to inspire entirely new paths forward.

So how will we think about the past in the future? The central question for this Dædalus issue asks artists and scholars to speculate about what aspects of our present historical moment will enrapture, haunt, and/or plague thinkers in the future. Inspired by Bennett Capers’s speculative law article about the future of policing in 2044, when the United States is projected to become a majority-minority country, I asked the contributors to conjure up the methodologies, theories, and scholarly and artistic practices we will need not only to rectify current harms but also to usher in more equitable futures.5 As Afrofuturist theorist Ytasha Womack has articulated, speculative thinking is “a way of bridging the future and the past and essentially helping to reimagine” the experiences of the many who are disadvantaged.6 Speculative thinking encourages us to envision ourselves outside of any obsolete, dated, and/or invalid systems, structures, and practices.

Part of the central claim for this issue of Dædalus is that scholars and artists in all disciplines need the space, time, and encouragement to think capaciously about the future. As the fall 2022 issue of Dædalus on “Institutions, Experts & the Loss of Trust” demonstrated, many in the public believe that our current institutions are broken. In their introduction, Henry E. Brady and Kay Lehman Schlozman write, “our times present challenges akin to previous revolutionary moments, such as the invention of the printing press, the French Revolution, or the industrial revolution, when old authorities were overthrown and new paradigms emerged. We must reestablish authority by finding new ways to legitimate institutions.”7 With respect, I would alter their final claim by proposing that we need to reestablish authority by granting Americans the license to imagine what this moment will look like in the future; the license to imagine what methodologies, archives, artistic works, theories, and pedagogies will need to exist to create institutions that will be deemed legitimate in the future; the license to both reestablish and establish anew.

Thus, the essays in this issue are intentionally eclectic and diffuse and yet also recursive and circular. Though the authors span from the natural sciences to the social sciences to the humanities and arts, they seem haunted by some similar issues like climate change and its impacts on our future lives, the role of AI and the future of human existence, which institutions will endure and which will fade away, and the future of knowledge production both within the academy (in its potential future iterations) and outside of it. The essays are written from different moments in the future, ranging from 2050 to 2100 to unspecified periods in the post–climate apocalypse. The authors may circle around topics that have been explored in previous issues of Dædalus, but they often end in surprising places. The invitation to think speculatively opens up doors to new vistas and vantage points.

Natalie Diaz’s moving poem “Indexing a Performance—: Let slip, hold sway” opens this issue, reminding the reader that “The Future is usually someone else’s. / We are in one right now—A Future, among many.” We are living in the future tense of our ancestors, those who came before us, and we are living in the past tense of our descendants, those who will come after us. For Diaz, a Pulitzer Prize–winning poet who was born on the Fort Mojave Indian Village in Needles, California, and who is an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Tribe (Akimel O’odham), past and future shimmer together in the form of the sequin: “Look at it move. That’s energy and I’m the one who put it there.”8

Since I was inspired by Bennett Capers’s aforementioned article “Afrofuturism, Critical Race Theory, and Policing in the Year 2044,” his is the first essay in this issue. He situates speculative thinking within an Afrofuturist tradition and imagines a future when our descendants will look back in dismay at our use of policing technologies. For Capers, a legal scholar at Fordham University, there is the possibility of a future in the aftermath of race-making, but it will require concerted and intentional changes to who makes our current technologies.9

In “Back to the Future for Taxation,” Ameek Ashok Ponda, a tax lawyer and partner at Sullivan & Worcester, writes from the vantage point of 2075, when the twentieth-century American taxation models (based on income and general consumption) have been overthrown. Imagining a future in which AI has been fully ensconced in our society, Ponda believes that we will have to reckon with ways to level the playing fields between humans and machines, and that our descendants will look back in shock at our inability to find a way out of our current regressive taxation models.10

Oskar Eustis, artistic director of The Public Theater in New York, likewise imagines that our descendants will look back at us with horror: in this case, feelings of horror about our current commodification of the arts. Arguing that most of human history has treated the arts, and theater in particular, as a human right, he imagines that our descendants will applaud public works programs like the Federal Theater Project in the 1930s, the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts in the 1960s, and the creation of a regional theater network in the 1970s as attempts to right the ship. He writes that in the future, “artistry will be recognized as a central attribute of being human.”11

Matt Bell, an award-winning novelist, provides a wry, humorous, and horrifying portrait of an apocalyptic climate-ravished future whose inhabitants try to imagine if we enjoyed our current lives preapocalypse. In his short story “Home Sweet NewHome,” corporate greed and its handmaiden civil/civic disregard render life surveilled and commodified in terms that echo Capers and Eustis.12

John Palfrey’s essay, “Future Problem-Solving: Artificial Intelligence & Other Wildly Complex Issues,” on the other hand, strikes a more optimistic tone, arguing that philanthropy is always futuristic, especially systems change–based philanthropy. For Palfrey, the president of the MacArthur Foundation, a more just future lies within our grasp if philanthropists can work collectively to help shape the future of AI. His view of the future focuses on the agency we have now.13

Similarly, Michael M. Crow and William B. Dabars’s essay locates fundamental shifts that academic institutions can pursue now to shape higher education in 2100. Thinking deeply about both scope and scale, Crow, the president of Arizona State University (ASU), and Dabars, a senior research fellow at ASU, examine the need to recognize the plurality of academic cultures. They argue that it is imperative to act now to meet the entangled challenges ahead. Eschewing doom scenarios about the future, they see the Age of Entanglement as offering new possibilities for knowledge production—once we are willing to change academic models rooted in the Age of Enlightenment.14

If the first set of essays focuses on American institutions that will radically change in the next century or more, the next set explores how knowledge production will or should change in the future. Perhaps offering the most optimistic vision of the future’s view of our current moment is Joshua LaBaer, an MD-PhD and leading expert in the field of personalized diagnostics. He projects that our descendants will recognize and applaud the seismic shift in biomedical practice that has occurred in the last hundred years. Moving from a scientific and medical model based on doctrine and legacy to one based on evidence and the scientific method, he predicts a future that will be grateful for our ability to shift models as quickly as we did.15

Joy Connolly, the president of the American Council for Learned Societies (ACLS), provides a bleaker portrait of knowledge production. Looking toward 2069, the 150th anniversary of the founding of the ACLS, Connolly imagines a future in which ancient studies is available only to students at elite schools; a luxury offered to and afforded by the few. As a challenge to this bleak future, Connolly offers an alternative: the creation of a new field of study of the ancient past that is not only global but also planetary in scope and scale.16

Madeline Sayet, an award-winning playwright, director, and actor, offers a short play that also considers which scopes and scales humans can understand. Let’s Get Lost in the Cycle of Time Together explores the interconnectedness of life over generations, and portrays humanity’s repeated, misguided attempts to isolate itself despite this interconnectedness.17

Choosing 2050 as the frame for his speculative thinking, Dan-el Padilla Peralta, a professor of classics at Princeton University, imagines a future awash in spoken languages, including ancient and alien ones. His essay “Speaking in Future Tongues: Languaging & the Gifts of Spirit” is a beautiful recitation on language, self, community, and what it takes to move beyond commodification. One of the few pieces to include thoughts on spirituality, Padilla Peralta’s essay offers hope for a more united future.18

Rounding out the knowledge production section, Jericho Brown’s poem “The Ground” provides a haunting portrait of a father and son digging in a garden. Like Padilla Peralta’s use of family memories to anchor his essay, Brown, a Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, examines how time, memory, and knowledge work through a family.19

The final pieces place climate change at the heart of their visions for the future. Lindy Elkins-Tanton, a planetary scientist whose research concerns terrestrial planetary evolution, thinks about a future with looming apocalypses and imagines that our future selves might be less separated from technology and, in some cases, from each other. Offering three different future possibilities—population decline, the creation of self-sustaining “Throughline” communities, and the eventual discovery of alien life—Elkins-Tanton sees different possible futures with divergent viewpoints about us, the Before Time people, as barbarians or, conversely, as technological gods.20

“Horseplay,” Leah Newsom’s short story, is set in a world that is post–climate disaster. Newsom, a novelist and short story writer, imagines that familiarity and the recursive will become fundamental to survival in this postapocalyptic world. And for those paying close attention, you will notice connections and similarities between Newsom’s story and Sayet’s short play: clipclopclipclopclipclop may be the sound of horse hooves, humans with coconuts, or the metronome of time, continuously ticking even as human life expires.21

I would be remiss if I did not mention the internal artwork in this issue. Like the cover art, the internal art is designed by Katie Burk of Good Work Burk, and the images capture three of the issue’s central themes: climate change, institutional change, and knowledge production change. And like every piece in this issue of Dædalus, the artworks are meant to provoke. What will our landscape look like in the future, and how does that landscape reflect where we are now? Which institutions will crumble, and how can our present actions stem, speed up, or alter that deterioration? How does AI and “model collapse” impact how knowledge production will occur in the future? And how will our actions look to us when we are faced with an Anne Boleyn-style six-fingered future?

I am left with the feeling that speculative thinking should be—needs to be—cultivated among our citizenry. We need to learn to flex our creative thinking about our institutions and the methods and archives we use to analyze and assess them. I am grateful to the writers included in this issue—the creative writers, humanists, social scientists, and scientists—for being willing to engage in this experiment, for being willing to dream up how we will think about our present historical moment in the future.

An enduring sense of recursiveness ends this issue of Dædalus with Anne Carson’s poem “How Pants.” Carson, the award-winning poet, playwright, and translator of ancient Greek, makes the reader consider time through repetition. The last line of her poem is “linger,” and I cannot imagine a better way to end the issue.22 What will linger? What will last? What will stay with our descendants in 2050, 2069, 2075, 2100, and beyond?