Lessons from the Digital Coalface in the Post-Truth Age: Researching the Middle East Amid Authenticity Vacuums, Transnational Repression & Disinformation

Drawing on thirteen years of personal experience researching Middle Eastern politics, I examine how digitality has eroded traditional boundaries between safety and danger, public and private, and democratic and authoritarian spaces. While digital tools initially promised to make research more accessible and secure, they have instead created new vulnerabilities through sophisticated spyware, state-sponsored harassment, and transnational repression. These challenges are compounded by the neoliberal university, which pushes researchers toward public engagement while offering little protection from its consequences. Moreover, the integrity of digital data itself has become increasingly questionable, as state actors and private companies deploy bots, fake personas, and coordinated disinformation campaigns that create “authenticity vacuums” in online spaces. This essay argues that these developments necessitate a fundamental reconsideration of digital research methodologies and ethics, offering practical recommendations for institutions and researchers to navigate this complex landscape while maintaining research integrity and protecting both researchers and their subjects.

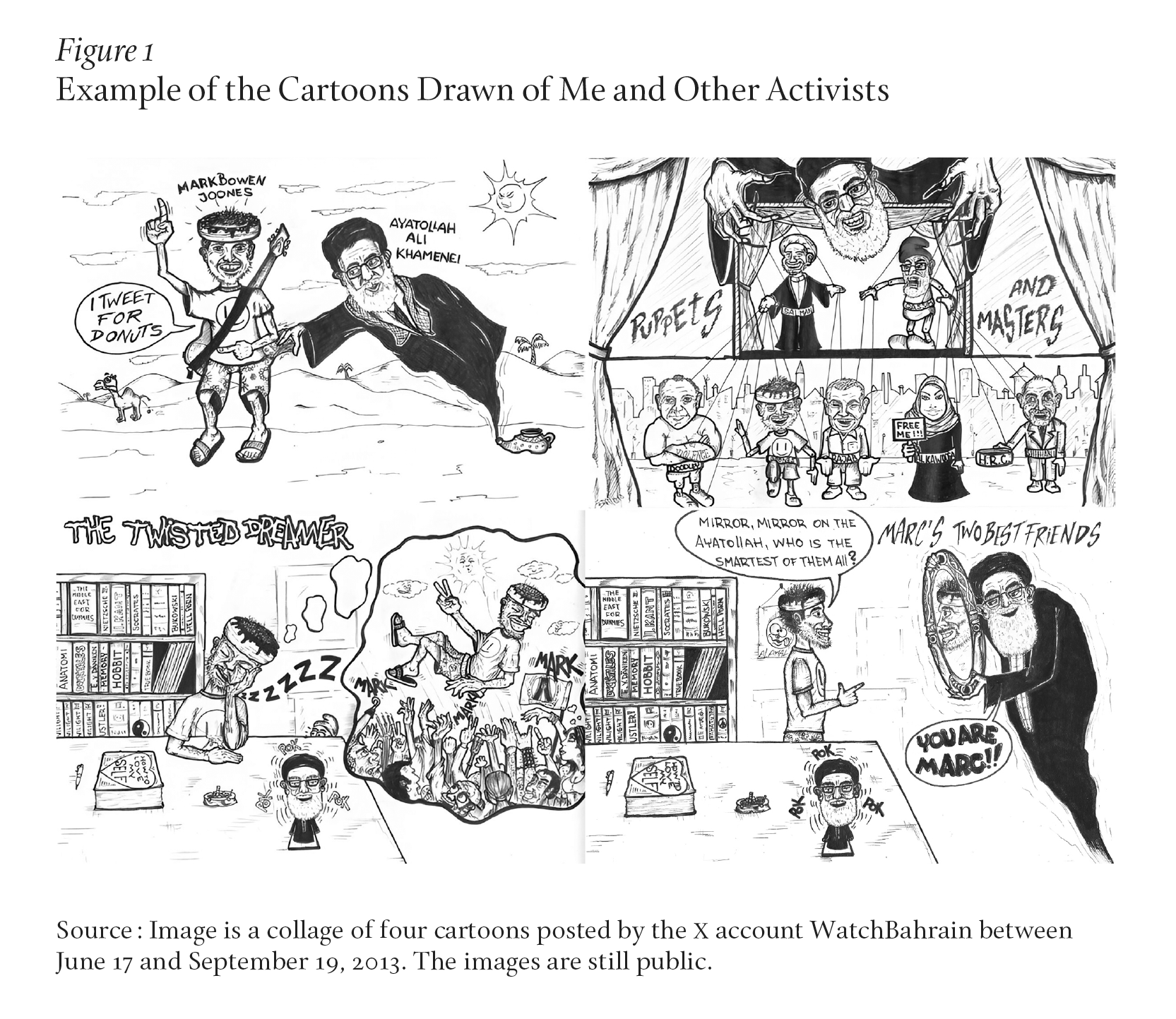

Since the Arab Spring, I’ve become an unwitting magnet for online harassment due to my writing on Gulf, and especially Bahraini, politics. I’ve received death and rape threats, been depicted as an Iranian puppet wearing a donut-shaped turban in (surprisingly good) caricatures, and even had social media impersonators spout opinions I don’t hold. According to my attackers, I’m somehow both gay and homophobic, a Qatari and Iranian stooge, Shiʿa, atheist, and a Western secret agent rolled into one. My friends have had their devices bugged, and I have mine checked regularly for intrusive electronic surveillance. I’ve drank coffee with activists arrested for merely sending a tweet. In 2012, I was banned from returning to Bahrain, the country where I grew up, for criticizing government repression on social media. Amid all this, I’ve watched the relentless online abuse take a serious toll on both me and others.

At the same time, I’ve also researched the sheer amount of deception, disinformation, and fakery online. I’ve identified countless bots, I’ve exposed journalists who do not even exist, and helped get online trolls suspended. All things considered, I’ve seen the dark side of researching with, on, and through social media in the “post-truth” age. In this essay, I draw on my thirteen years of personal experience conducting online research in the Middle East and highlight the challenges of digital research in difficult political climates and within a broader context of the neoliberal and reputational university. I discuss the challenges of dealing with social media companies, the impact of targeted harassment campaigns on researchers, and the constantly changing nature of digital threats. Crucially, I also explore the epistemic problems and assumptions of digital data, an increasingly important component of contemporary research, especially as we enter an era of generative AI. Understanding these issues is vital to developing training and strategies to help researchers conduct their work responsibly and safely, but also with validity.

Digital technology has had a multifaceted impact on academia. It has changed both how research can be done and the nature of the research questions asked. It has impacted how research is disseminated. It has transformed the dangers and ethical dilemmas faced by those involved in research. For many social scientists and humanities scholars, including area-studies experts, digital tools and platforms were initially welcomed, as they allowed researchers to engage with their work remotely and connect with the places and people they study in new ways. However, this shift to digital introduces significant challenges to researchers, and especially to those researching authoritarian and illiberal contexts. The same digital technologies that keep researchers connected to their subjects also prevent them from entirely escaping the reach of the people and institutions in power in the regions they are studying. Similarly, digital technology has raised questions about data reliability, and sharpened questions about the blurring and fracturing of barriers between truth and fiction, safety and danger, and authoritarian and democratic contexts.

Digitality here means nothing more than the condition of living in a digital culture, especially with regard to the seeming ubiquity of social networking sites, streaming platforms, blogs, and mobile devices. For many academics, digitality is unavoidable. However, its inexorable rise is not devoid of political and economic drivers. In many regards, the neoliberal context has foisted digitality upon us. There has been growing pressure on researchers to make their work “impactful” and widely recognized.1 There is a logic to this, of course. There are numerous benefits of public scholarship, such as increased visibility, professional advancement, and the presumed positive impact on society, academia, and individual researchers.2 In a post-truth age, the public’s declining trust in media and academia only intensifies the need for experts to contribute their knowledge. Academics still hold a significant trust advantage over journalists, and their contributions can help improve the accuracy and credibility of news.3 Social media can also serve as a powerful tool for uncovering abuses of power. Like legacy media, it has been instrumental in bringing to light instances of misconduct, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and various other types of discrimination, harassment, and violence.4

However, even when social media serves as a tool to expose injustice, it can raise ethical dilemmas. In one instance, for example, in 2020, an American academic was forced to withdraw from a project on women’s entrepreneurship in Qatar after a screenshot of a long-deleted blog post from 2008 resurfaced online. The blog post, which featured a forwarded email, contained numerous racist and xenophobic comments about “locals” in Qatar.5 This occasion raised another potentially troubling dimension of social media: a more-than-decade-old deleted post can cast a long, apparently indelible shadow, pointing to what has been called “context collapse.”6 Context collapse is the process by which multiple audiences across time and place are flattened into a single “context.” Social media allows us, academics or otherwise, to be “perpetually or periodically stigmatized as a consequence of a specific action performed in the past.”7 The persistence of digital content over time—also known as “time collapse”—is one of several dimensions in which digitality appears to contribute to the dissolution of conventional boundaries, as between the public and private, the professional and social, the past and present.8 Indeed, it can be weaponized to attack and undermine the human capacity to change and develop.

In addition to these pull factors, which make academics enthusiastic about using social media to promote their own research, are push factors, which might pressure otherwise reluctant academics to use social media. The rise of branding within the neoliberal university environment has also pushed communications teams and reputation to the forefront of universities’ agendas. Paraphrasing Dan Schawbel, media scholar Alison Hearn argues, “new forms of social media have inaugurated the rise of a reputation economy, where aggregated reputation, generated by branding and promotion online and off, threatens to displace all other forms of value.”9 Hearn further claims that “the function of university branding is to legitimate and perpetuate the university’s new role as a site for the circulation and accumulation of global finance and knowledge capital.”10 Thus, on the one hand, academics are encouraged to engage with the public so the university can leverage its own reputational benefits for its brand but, on the other hand, they are subject to scrutiny and face the possibility that their contributions are perceived as detrimental to the university’s reputation. Thus, anything that might adversely impact brand or reputational value, such as the opinions of its employees, are a potential reputational cost. Consequently, many academics believe their social media posts are monitored for perceived criticism or anything harmful to their university’s brand.11 Indeed, as Brady Robards and Darren Graf write: “This hidden curriculum of surveillance works to produce compliant, self-governing citizen-employees. They are pushed to curate often highly sterile representations of their lives on social media, always under threat of employment doom.”12

As a case in point, while employed as faculty at a university in the United Kingdom, I sent a tweet from an account I ran that was connected to a university institute. The central administration immediately contacted the department administrator to find out who sent the tweet. They feared the phrasing of my tweet drew too much attention to recent accusations of Islamophobia at the university, and deleted it without my consent. They also advised “whoever” sent it to take social media training. Ironically, my domain of expertise happens to be social media. Similar stories abounded during academic pension strikes in 2018. These strikes, the largest in the history of UK higher education, revolved around changes to academic pensions schemes.13 Thousands of academics around the United Kingdom, including myself, formed picket lines and went on strike. As with other protest movements, social media was an important tool for mobilization, documentation, and solidarity. However, academics in various institutions were censured by their administrations for the “wrong” type of social media activity—that is to say, any activity that may have cast the university in negative light.14

Beyond the professional sphere, the existence of context and time collapse on social media also means that academics’ private and social lives are increasingly difficult to keep separate. Private activities disclosed on social media platforms may also be used against the academic to attack their credibility. This could be anything from their sexuality, their lifestyle choices, or their religious beliefs, to name a few examples. Digitality, plus the rise of the reputational university, raises issues of how scandal itself, irrespective of veracity or the presence of wrongdoing, is sufficient to censure the academic who is the subject of it. Digital media has created a blurring, a dissolving of boundaries, between public and private, the scientist and public intellectual, past and present, traditional versus digital methodologies, professional profile and anonymity, and, as we shall see, safety and danger, fact and fiction.

Scholars increasingly face harassment from politically partisan and sometimes openly bigoted groups on social media. Studies indicate that this issue disproportionately affects minorities and women, subjecting them to hate and discrimination including racism, sexism, transphobia, xenophobia, and ableism.15 Examples abound: In one instance, an educator was fired for posting photos of herself at a drag show on her personal Facebook account.16 In the Middle East and North Africa region, authorities have targeted lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals on social media and dating apps, subjecting them to online extortion, harassment, and public exposure. They have also used unlawfully obtained digital photos, chats, and other private information as evidence in prosecutions, violating the defendants’ rights to privacy, due process, and other fundamental human rights.17

X (formerly Twitter) is often used to intimidate academics into silence. Such attacks can “terrify and paralyze” academics, as attackers try to “silence, shame, humiliate, bully, intimidate, threaten, terrorize and virtually destroy their human target.”18 This abuse can be augmented by the “online disinhibition effect”: that is, how the internet and anonymity enable people to behave and self-disclose in ways they would not face-to-face.19 Here, the boundaries of the “self” are also eroding. As psychologist John Suler adds, “The absence of face-to-face cues, combined with text-based communication, can significantly alter an individual’s sense of self-boundaries. People may feel as if their minds have merged with that of their online companions.”20

Unlike academic critiques (usually), these online attacks can be deeply offensive and personal, causing significant emotional and psychological distress. The visibility of academics, especially when their contact information is easily accessible through institutional websites, increases their vulnerability to these attacks, exposing them to both online and offline harassment. Being on social media increases the risk of harassment such that it “compromises well-being at work.”21 Indeed, the rise of post-truth populist politics has been characterized by attacks on “experts.” The role of legacy media, particularly sensationalist outlets, can exacerbate the situation by negatively framing academic efforts for social change, further inciting public backlash against the researcher and their work. This is particularly true for scholar-activists, who often require or obtain publicity through their efforts to create social or political change. This creates a hostile environment that not only affects the individual but can also deter others from engaging in impactful research due to fear of similar treatment.

Activists’ and academics’ timelines are often mined for potential “gotcha” moments. During Israel’s ongoing blockade and illegal occupation of Gaza, and immediately following the October 7 Hamas-led attacks against Israel, criticism of Israel’s campaign in Gaza as genocidal led to provocative and dangerous charges of antisemitism in the press against those critics. A journalist from the mainstream but right-wing British newspaper The Daily Telegraph began combing through my tweets and those of other fellow board members of the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), an NGO committed to highlighting human rights abuses in Bahrain, for any content they could misrepresent as antisemitic. (BIRD also acts as the secretariat for the UK’s All-Party Parliamentary Group on Democracy and Human Rights in the Gulf.) The Telegraph’s main target was Sayed AlWadaei, a Bahraini activist living in exile in the United Kingdom and a board member of BIRD. The journalist was attempting a character assassination of AlWadaei, who had recently won a court case against Tory MP Bob Stewart (and thus provoked Tory ire) for a racially aggravated public order offense.

Although the journalist had initially wished to include me in the piece, the main intent was clearly to try to discredit AlWadaei (and his colleagues) by characterizing his use of the terms “genocide” and “apartheid” as somehow “antisemitic.”22 Of course, the tweets were not antisemitic, but this highlights how journalists working with a particular agenda can mine social media for spurious accusations to attack those they see as political adversaries. Whether through misrepresentation or decontextualizing information, social media timelines can be easily repurposed for audiences who have no knowledge of those being targeted. For activists like AlWadaei, these types of harassment and smear campaigns can potentially jeopardize the work they do, as they give a veneer of media legitimacy to those (such as the Bahrain government) who might wish to pass similar deleterious press clippings on to funders or politicians.

Perpetrators of this kind of defamation often face little to no repercussions, leaving victims to cope with the abuse largely on their own. This situation highlights the necessity for universities and other institutions to develop robust support systems and protective measures for academics engaging with the public, particularly in the volatile space of social media. Protective measures are crucial in safeguarding the well-being of researchers and the integrity of their work. Unfortunately, academic institutions may encourage impact but renege on their responsibility to protect academics, especially when they fear reputational costs. While colleagues may offer sympathy, the institutions themselves often lack the mechanisms or policies to protect and support their staff effectively in the face of public scrutiny and backlash.

In such cases, universities should help their faculty through instances of harassment and provide legal support, should instances of defamation occur. Occupational support, like specialized trauma counseling, should also be offered to affected faculty. And university communications teams should pursue “right of reply” opportunities on behalf of or by those targeted to give them an opportunity in a suitably high-profile publication to defend their position.

While the neoliberal university brings with it its own set of issues with regard to the growth of digitality, for researchers studying the Middle East or other authoritarian contexts, there are additional sets of problems. The rise of spyware, automated bots, and misinformation campaigns present real threats to their safety and the accuracy of their research, regardless of their physical location. In many ways, a new form of context collapse—spatial collapse—has occurred in the research field. Communicative technologies transcend physical and geographic barriers. The digital space has eroded sovereign boundaries between authoritarian and nonauthoritarian contexts.

Despite this, the techno-utopianism that tends to follow groundbreaking changes in technology (such as the rise of social media or generative AI) has tended to focus the debate on the positives. There is good reason for this, especially in terms of methods. For example, researchers have noted that research can be improved by a combination of in-person and digital ethnography. Social media scholar Dhiraj Murthy has argued “that a balanced combination of physical and digital ethnography not only gives researchers a larger and more exciting array of methods, but also enables them to demarginalize the voice of respondents.”23

This generally positive assessment has been reflected in some work on the Middle East, especially as the violence and instability that resulted from the Arab uprisings sparked interest in remote methodologies. Anthropologist Marieke Brandt has argued that while anthropology traditionally values in-person fieldwork, political instability necessitated a shift to digital research methods, which allowed continued contact with displaced populations and inaccessible regions.24 Brandt highlights several advantages of digital research: increased openness from participants due to anonymity, more genuine dialogues free from self-censorship, extended engagement opportunities, and efficient data transcription. She notes that digital communication eroded distances and borders, while on-the-ground realities revealed “militarised sites of immobility and surveillance, controlling and restricting our movements.”25 This juxtaposition underscores a recurring theme of blurring boundaries in digital research contexts. Even here, Brandt infers the breaking down of “barriers” through the digital: between militarized and nonmilitarized, or surveillance and absence of surveillance, or local and “non-local.”

Furthermore, the dangers faced by researchers working in the Middle East have also validated some concerns about the risks of in-person research. Matthew Hedges, a British PhD student, was arrested in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), kept in solitary confinement where he was reportedly fed a cocktail of drugs, and found guilty of espionage and sentenced to life imprisonment (before he received a pardon).26 Kylie Moore-Gilbert, an Australian academic, was imprisoned in Iran on accusations of espionage after being invited to a summer school at an Iranian university.27 One of the most well-publicized cases was Giulio Regeni, the Italian PhD student at Cambridge University who was tortured and murdered by Egyptian security forces while doing field research in Egypt.28 These examples highlight potential dangers faced by Western researchers in the Middle East. Some, such as the case of Matthew Hedges, have revealed how even research in authoritarian countries traditionally considered “safe” (such as the UAE) can be unpredictable for researchers.

Yet the solution to the challenges of in-person research may not be the quick digital fix that the optimists hoped for. While such effusive narratives tended to coincide with the initial buzz around new technology, experience has tempered such enthusiasm. The counterrevolution that followed the Arab uprisings has resulted in the increased securitization of the digital space.29 Digital technology has increasingly been co-opted as a space of surveillance and monitoring. Collecting ethnographic data digitally presents distinct obstacles for social scientists because interactions are mediated through computers that may or may not be secure. Recognizing the potential risks faced by participants from vulnerable groups, the necessary sensitivity of researchers in managing social relations can thereby influence the wider practice of digital ethnography. Ethical considerations include focusing on the selection of the field, the researcher’s role, the subjects, and how data are represented.30

Indeed, the digital can become a risk itself. As projects rely on technology for communication, data storage, and collaborative analysis, local research assistants (RAs) are burdened with ensuring secure internet connections, safe communication technologies, and reliable data storage methods. This is especially concerning in areas under heavy surveillance, where authorities closely monitor researchers’ communications.31 Specifically, the researcher, or the researcher’s RA, if active online, may be exposed to digital harm through surveillance, harassment, and doxing. It may also create a more exploitative dynamic between the locally situated RA and the researcher. Choosing to use a local RA on the basis that the “field” is too dangerous for the researcher (but apparently not for the RA) raises issues of power dynamics between those in positions of privilege and those who are not.

While this has had a chilling effect on some academics who have chosen to avoid visiting certain regions, developments in technology and states’ willingness to deploy it have meant that researchers working from afar are still not beyond the reach of authoritarian regimes, whether in liberal democracies or otherwise. There are dangers for both researchers and subjects themselves. Digital technology and projects can form part of the architectures of control. Although there is less time to investigate these more meta levels of surveillance, the affordances of digital technology to allow “remote” fieldwork can lead to a false sense of security. The new affordances of technologies have also benefited authoritarian and illiberal governments, lowering the costs for censorship and extending the reach of remote repression. In other words, staying in one’s home institution and eschewing fieldwork in the country does not obviate the dangers wrought by digital technology.

The development of sophisticated spyware and its use by unaccountable authoritarian regimes is threatening privacy as we know it. One example is Pegasus spyware. Developed by the Israeli cyberarms firm NSO Group, Pegasus is a highly sophisticated malware that infiltrates iOS and Android devices to enable the remote surveillance of users. Once installed, it can read text messages, track calls, collect passwords, trace the phone’s location, access the target device’s microphone and camera, and gather information from apps. Pegasus is known for its stealthy operation and ability to exploit vulnerabilities in smartphone software, making it a powerful tool for spying on individuals, including journalists, activists, and government officials.32

We know transnational repression via spyware is widespread. NSO claims clients in forty countries, among them several national governments. When The Guardian (and others) accessed a list of targets of Pegasus, the extent of surveillance was shocking. Included on the list were figures “such as Roula Khalaf, the editor of The Financial Times, who was deputy editor when her number appeared in the data in 2018.”33 Also targeted was the human rights lawyer Rodney Dixon KC, who has acted as counsel for Matthew Hedges and the fiancé of murdered Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Hatice Cengiz. Analysis of the data suggests Dixon’s number was among a small group of UK numbers that appear to have been targeted for surveillance by Saudi Arabia.34

More than a dozen academics from at least five different countries were also targeted by Pegasus.35 One of these was Madawi al-Rasheed, a Saudi Arabian scholar who resided in the United Kingdom and who was at the time a visiting professor at the London School of Economics.36 Al-Rasheed wrote, “My work to expose the crimes of the Saudi regime led to a hacking attempt on my phone. Today, I am overwhelmed by feelings of vulnerability and intrusion.”37

Some of the biggest customers of Pegasus have included Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and possibly Morocco. Hedges, after his imprisonment and torture in the UAE, warned journalists and campaigners attending the COP28 climate conference in Dubai to take precautions for their physical and digital security. Hedges’s concerns were based on the fact that his phone number was on a list of Pegasus Spyware targets. This also raises issues for academic events (or any events) that might be held in countries that have access to such spyware. Should conference organizers, for example, consider the possibility of intrusive electronic surveillance when organizing conferences?

Pegasus was not the first and will not be the last form of sophisticated spyware. Before Pegasus was FinFisher, developed by the European company Gamma International. Ala’a Shehabi, a British-Bahraini journalist, university lecturer, and activist who lives in London, was among those targeted using FinFisher.38 As a colleague of Shehabi in the NGO Bahrain Watch, I was concerned. Scholars, activists, and scholar-activists tend to find themselves incurring the wrath of authoritarian or illiberal regimes. The spyware targeting prompted a degree of paranoia. Had we also been targeted? What if our devices had been infected? If compromised, how might this impact our vulnerable contacts, particular those in Bahrain?

Digitality has also widened the dragnet of surveillance. The functionalities and affordances of surveillance technology should prompt a renewed “critical interrogation of the one-sided focus on researcher safety and troubles notions of researcher responsibility.”39 Indeed, while there has been a tendency to focus on researcher safety, especially for those in the Global North, spyware can implicate those connected communicatively to the researcher. What many fail to understand about spyware is that infection of an individual also compromises their network of contacts. For example, in the case of Madawi al-Rasheed, while her device was the one compromised, it could theoretically allow the hacker to read messages that al-Rasheed’s contacts sent to her. Thus, the net cast is much wider than the individual. These attacks were, in many ways, violations of sovereignty by British allies—a blurring of sovereign boundaries, but also a blurring of the individual, al-Rasheed, and her personal social network. Unfortunately, there seems to be a lack of consequences for allies who engage in this form of surveillance.

It is important to bear in mind that these attacks by foreign states are examples of transnational repression: attacks on people by foreign states outside their sovereign borders. While surveillance by foreign states of perceived “dissidents” abroad is not new, the safety of territoriality has been altered by digital technology, as has the way we store personal information and that of informants. We must be protective of our privacy not just for our own sake, but for the sake of those digitally connected to us.

Having said that, while it’s crucial for everyone to focus on data privacy and safety, they must not give in to the anxiety and dread that malicious actors aim to instill. According to cyber researcher John Scott-Railton, “that fear is what these organizations feed on.”40 Well-documented violations of privacy can discourage or discredit research on authoritarian regimes. In many ways there is an inherent paradox: raising awareness and knowledge of digital spyware can also promote a chilling effect. The more we know, the more we may fear. The antidote to this is of course more digital literacy, through which we feel confident and empowered in our own digital hygiene. Assistance from our institutions, whether through up-to-date training or technical support, would be most valuable. Even if universities cannot offer in-house technical support, there should be some mechanism or entity tasked with providing such services to researchers. In my own experience, having one’s phone checked for spyware is often done through personal contacts and networks. This informal, ad-hoc approach is suboptimal.

Beyond sophisticated spyware, self-disclosure on social media has also prompted states to punish activists and academics—a component of rhizomatic surveillance (the idea that surveillance networks can be nonhierarchical and connect at any point).41 In Bahrain in 2011, for example, students and activists who posted critically of the government or ruling family on Facebook and YouTube were punished, either by losing their scholarships or being arrested.42 Comparative humanities scholar Mike Diboll was fired from Bahrain Polytechnic in 2011 due to his social media activity. His Facebook activity was printed out during a disciplinary hearing as evidence of his “deviance.”43 In such cases, the “honeymoon” period of these new technologies, when people perhaps abandoned caution in part due to the utopian narratives around social media, may have led people to engage in dangerous behaviors. After the honeymoon, academics and activists in Bahrain stopped communicating using social media due to fears that the mukhabarat (intelligence agencies) monitored it and that any visible association with someone critical of the regime would be sufficient to prompt suspicion.

Indeed, the nuances of specific social media platforms must also be learned by academics wishing to use them for research. As a case in point, during the Arab uprisings, it was common for anonymous accounts to tag the respective ministry of interior’s account with people they deemed critics of the government. While the minister of interior probably did not monitor their replies, this was enough to generate substantial anxiety for some people tagged.44 On other occasions, limited privacy settings meant progovernment supporters could trawl the social media accounts of others, looking for “evidence” of disloyalty and subsequently doxing critics. I was informed by my own contact in Bahrain that my social media activity (albeit public) had essentially been the reason for me being banned from entering the country.

The emergence of cyber vigilantes, who name and shame government critics, has also been a disturbing phenomenon. I heard from people who, after being men-tioned by certain progovernment accounts, would pack a suitcase and put it by their door, waiting for the knock at 3 a.m. by security forces.45 In Bahrain in 2011, the pitch of online harassment was so severe that one prominent Twitter troll called 7areghum (translation: the one that burns them) was singled out by an independent legal committee tasked with investigating the Bahrain uprising. The committee argued that the account targeted antigovernment protesters, revealing their locations and personal information and subjecting them to harassment, threats, and defamation. The committee even concluded that the account placed individuals in immediate danger and likely breached international law. Despite this, nothing was done, and no one was arrested.

The fear of surveillance can end relationships. Even an academic friend of mine no longer wishes to risk communicating with me via digital technology, regardless of what country we are in or what technology we use. The perception that the authorities of their particular government, based on a good understanding of their capabilities, have eyes and ears everywhere is such that our friendship cannot actually exist in any form. This has made for some awkward social occasions at mutual friends’ events, where extra attention must be paid to not accidentally appear in photos together (although even this must be coordinated without directly communicating).

Governments and state-aligned entities often employ trolling as a technique to attack critics. The affordances of digital technology allow for large-scale digital violence, sometimes called mobbing or brigading. As I have written elsewhere, “The sheer velocity of tweets, the virality, and the ‘breakout’ is in itself a distinct aspect of a modality of violence. The velocity accentuates the severity of the attack, just as a savage beating is different from a single punch.”46 While undertaking my PhD on political repression in Bahrain, I came under all sorts of attacks on social media. From death threats and threats of rape to websites devoted to attacking me and other activists or researchers. A website traced back to the Czech Republic even published caricatures of me and other activists, accusing us of being “Iran-backed” agents (Figure 1). In one instance, I received a threat of legal action if I did not refrain from commenting online about the dubious credentials of an academic who had misled others about his qualifications and was subsequently acting as an apologist for the Bahrain government’s killing of protesters.

Cyber-vigilantism can often take on a far more systematic and seemingly institutional form. The pro-Israel website Canary Mission is perhaps one of the most well-organized and established means of attacking academics online. Canary Mission is essentially a name-and-shame platform. The website documents academics and students deemed to be critical of Israel. Students have reported that appearing on the website has given them anxiety and in some cases forced them to step back from activism.47 Among my own experiences, I had a student who decided against doing research on the Canary Mission website due to fear of it resulting in her being put on the website. Needless to say, much of the “evidence” provided by Canary Mission consists of social media posts. How universities respond to cyber-vigilantism and spurious smear campaigns should also be scrutinized. In 2025, Goldsmiths University in London apologized and paid damages to lecturer Ray Campbell after suspending him for five months over allegations of antisemitism on social media. The allegations, which were later dismissed as unfounded following an investigation, were based on social media posts collected by GnasherJew, an anonymous pro-Israel monitoring group.48 The use of vexatious and ultimately unwarranted complaints against academics’ social media activity to suspend and discredit scholars reflects a troubling “punish now, ask questions later” approach by the reputational university.

Indeed, criticism of Israel, especially in the United States, has been used as a means of denying opportunities to people at academic institutions. Kenneth Roth, for example, was initially denied a fellowship at Harvard for his criticism of Israel in the course of his job as director at Human Rights Watch.49 In late 2023, various students had job offers withdrawn due to their criticism of Israel. In some cases, social media posts were used as the basis to rescind offers.50 A decade earlier, a professor was refused tenure for tweeting critically about Israel.51 Other academics were harassed en masse, such as Nader Hashemi for saying on a podcast that Mossad could have been one of several entities involved in the attack on Salman Rushdie.52 Again, these illiberal practices demonstrate how regimes or other entities, regardless of whether they are authoritarian or democratic, are using social media and self-disclosure to punish academics. In this way, digitality facilities witch hunts and evidentiary trails that may be used to harm the career or life chances of academics. Even now, my colleagues are debating whether it is safe to attend conferences in the United States after a French scientist was denied entry because border agents found private communications criticizing the Trump administration’s research policy. This has been compounded by the fact the U.S. administration has announced they will use generative AI to scan student timelines for “pro-Hamas” content. Often the term “pro-Hamas” just means sympathy to Palestine or criticism of Israel.53

A key element of “blurring” boundaries enabled by digital technology is the proliferation of digital data, itself increasingly an object of study, whether from social media, databases, or secondary sources on websites or forums. However, while a lot has been written on the ethics of researcher and subject safety as well as new digital forms of harm, less attention has been given to the truthfulness and veracity of the data being collected. It is important to consider the nature of the data being collected. Working remotely does not necessarily only entail traditional ethnographic techniques such as interview or observation being mediated by technology, it also involves the study of new forms of data, big or small, textual or visual. The study of social media has also transcended disciplines, becoming a zeitgeist in its own right. The term “social media analytics” has gained a great deal of attention. It is defined as “an emerging interdisciplinary research field that aims on combining, extending, and adapting methods for analysis of social media data.”54 Key to data collection are the four Vs: volume, velocity, variety, and veracity. Of particular relevance here is “veracity.”55 Researchers Tatiana Lukoianova and Victoria L. Rubin define the three dimensions of veracity as objectivity, truthfulness, and credibility.56 “Social media promise a complete and real-time record of ‘natural’ user activities.” However, “spam and missing data both compromise the veracity of the data.”57 Added to this is the fact that the researcher cannot determine the veracity of such large amounts of data. Put simply, how do they know who is truly behind the comments they are collecting? If not, then what, or who, can we say it represents?

The existence of troll and bot farms—organized entities composed of internet trolls or automated bots that aim to manipulate public discourse, influence political narratives and disrupt decision-making processes within a given society—is a serious problem on social media.58 In my own work examining the nature of online interactions, it is clear that social media data are not only not a reflection of public opinion (and never were) but are also corrupted by a multitude of factors. I’ve found bot and troll networks operating all across the MENA region, from Tunisia and Algeria to Lebanon and Yemen. Most of the time, it is difficult to determine who is behind them. There are exceptions of course. In a study of online hate speech, I found that thousands of the tweets I was analyzing were produced by bots belonging to a Saudi TV channel. Bots are fake, automated accounts that are designed to look like real individuals but are controlled centrally by a software program created by a particular entity. The bots I identified were promoting anti-Shiʿa sectarian hate speech. This would give a layperson, or at least someone not well versed in digital technology, the illusion that genuine anti-Shiʿa hate speech was much more endemic than might be the case.59 This was at a time when scholars were documenting the prevalence and distribution of hate speech online but were not sure of (or were not upfront about) to what extent bots might have impacted their data. Similarly, during the Gulf crisis of 2017, when Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt severed relations with Qatar, I found that for months, the majority of tweets mentioning the word “Qatar” were being produced by bots or trolls. In other words, anyone doing digital research about Qatar, or indeed the Gulf, would have a greater probability of finding a post by a bot or troll spreading propaganda.60 Technology such as generative AI is only going to exacerbate the problem. In 2024, for example, I exposed an astroturfing campaign later linked to STOIC, a Tel Aviv–based firm. This campaign, reportedly funded by the Israeli Ministry of Diaspora Affairs, used AI-generated content, sockpuppet accounts, and manipulated narratives to push pro-Israel messaging, stoke anti-Muslim sentiment, and undermine solidarity movements in the United States and Canada.61

It would be fair to assume that many people believe that social media companies are concerned about data “veracity.” My interactions with Twitter suggested otherwise. When I raised the issue of hate speech bots with Twitter in 2016, they thanked me, but did not acknowledge the accounts as bots or automatons, only that they had engaged in “spam-like” behavior. In this regard, the accounts were only deleted because their spam-like behavior was a problem. They were not deleted because they were fake accounts trying to give the illusion of grassroots public opinion. An unwillingness to recognize this problem or phenomenon again reflects how social media companies have become gatekeepers on what might be considered legitimate communicative activity in the digital public sphere, and who may be considered legitimate online personas. Authenticity, or inauthenticity, did not seem to be a major concern.

Political pressure on Twitter eventually caused them to adopt some measures of transparency. For a brief period of time, Twitter published lists of bot and troll accounts that were suspended due to being part of state-backed influence operations. Interestingly, collating this data revealed that the biggest government manipulators of Twitter in terms of total accounts suspended were Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain. Similarly, Meta, since around 2018, has published reports on what they call “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” These are attempts by states or other actors to manipulate public conversations and interfere in the research field. That Meta uses the term “inauthentic” is a particularly pertinent reminder of how data created on social media may not be an appropriate reflection of what real people think. Nonetheless, this type of documentation, which consists mostly of summaries, does little to help academics beyond making them aware that the data are manipulated. What’s more, these reports reveal only what social media companies want people to know. Indeed, absent from Twitter’s list were bot or sockpuppet accounts used, for example, by democracies such as the United States, even though we know the U.S. military has deployed such campaigns.62 This raises questions about whose manipulation of reality is subject to transparency and scrutiny.

Indeed, the more I conduct online research, the more uncertain I am that veracity of data should even be a default assumption in digital research. For so long, an epistemological assumption of social media data has been that a social media account represents a living, real individual who is not acting with ulterior motives or under duress. A necessary precaution for digital research may be to challenge or even reverse this assumption. This has become a more pressing issue since, for example, the takeover of Twitter by Elon Musk. Musk’s changes to X undermined previous attempts to ensure that people could have their identity corroborated, or “verified.” Now anyone with a credit card can obtain verification, enabling propagandists who pay for verification to create fake accounts that subsequently spread progovernment propaganda (with verified accounts receiving preferential treatment in terms of visibility on other users’ timelines). For example, a research investigation I conducted showed a number of verified-but-fake X accounts spreading pro-UAE propaganda around the COP28 summit.63 This deception can then spiral and go beyond social media and infiltrate other sources, such as news outlets. Indeed, many of the verified-but-fake accounts or “trolls” spreading propaganda about COP28 were then used as “vox pops” in other media.64 This process, known as “breakout,” is when narratives from social media are picked up and amplified in legacy media. If these subsequent reports then provide the basis for other secondary data collection, they compound the problem of data integrity—a sort of botception, if you will.

Research has already demonstrated that online conversations in the Gulf tend to be elite-driven.65 There is “strong evidence of state actors manipulating discourse on Twitter through direct intervention, offline coercion, or co-optation of existing social media ‘influencers,’ and the mass production of online statements via automated ‘bot’ accounts.” The purpose of pro-regime bots is to manipulate and secure “organic participation from supportive publics.”66 In addition to the prevalence of fake accounts or limited numbers of co-opted influencers, as knowledge of surveillance increases, so has caution and trepidation about interacting with researchers online. Fear of surveillance compromises the ability of digital technology to be used as a means of articulating rights claims and engaging in the discursive contestation of political or social issues. This may create “authenticity vacuums,” in which genuine online speech, undertaken without fear or favor, is missing. In most Gulf countries, for example, online dissent (however broadly conceived) is prohibited and actively discouraged. The internet is seen as an opportunity to build reputational capital, presenting the countries as a magnet for foreign investment and tourism. In this context, nation branding is essential. Consequently, the only forms of discourse that are encouraged are those that glorify the regime, commend government accomplishments, support capital flow, or aid in developing the “internet of things.” The occurrence of “pro-authoritarian” rhetoric, when organic, is also indicative of the potential vacuum left due to the fear people might feel about engaging in criticism.67 Taken together, the absence of real people engaging in discussions online, along with the proliferation of bots and loyalists boosting state propaganda, may result in social media spaces becoming an “autonomous civil society.”68 In this context, autonomous does not mean self-sustaining but rather a place of automatons. One has to wonder what kind of sociological questions may be asked of the social media data being produced in such contexts.

Academics also need to be cautious about being instrumentalized as part of influence operations. After all, academics generally may be seen as credible interlocutors on matters of political importance, and thus viewed as influential in adjacent policy fields. In one instance, a Saudi activist in Washington, D.C., was approached on Twitter by an account later linked to an Iranian influence operation. The account, a classic honeytrap, asked the academic to share links to fabricated articles masquerading as content on legitimate websites.69 The articles in question reflected a pro-Iranian position. In another instance, a colleague was approached by a journalist asking him to share articles published on real news outlets, including Newsmax and The National Interest. The articles themselves focused on critiques of political Islam. However, the author in question, who had written numerous articles for high-profile outlets, was using the stolen image of an entrepreneur from California. In other words, he did not exist.

The rise of deception has even made secondary sourcing on less dynamic platforms risky. News websites are not immune to manipulation. Sometimes the scale of the deception is staggering. An investigation conducted by me and Adam Rawnsley for the Daily Beast uncovered an astonishing and widespread operation.70 Nearly fifty international news outlets together published more than one hundred op-eds by journalists who did not exist. A bad actor, most likely a PR firm contracted by a government, had created fake profiles of journalists using stolen Facebook photos and AI-generated images. They then convinced editors to publish propagandistic articles about Middle East politics.71 This type of deception is increasingly common. If researchers had taken such articles as valid secondary sources, they too would be reproducing “tainted data” of unclear provenance. The reason this campaign worked was disturbingly simple: the editors did not do a video interview with the journalists who submitted articles. If they had, they would have seen that the “journalists” submitting articles were not the same person as in their photos. Of course, AI can now even generate convincing video clones, highlighting the need to develop new detection strategies. The whole incident suggests an unhealthy trust in an increasingly complex digital space. Again, digital literacy courses at universities using comprehensive cases studies would help mitigate such risks.

Although we did not discover who was behind this operation, such campaigns are often run by corporations working on behalf of state clients. It’s important to reemphasize that those responsible for such disinformation campaigns or manipulations of information integrity are not always authoritarian states. Indeed, the existence of an “influence industry,” in which companies, often in Western democracies, sell what is essentially disinformation and propaganda to wealthy clients (states or otherwise), is a key aspect of the distorting of public discourse in the digital sphere. These deception supply chains, as I term them, generate illiberal practices that unite corporations and/or elites across political and geographic boundaries.72 There are many examples, the most famous being perhaps Bell Pottinger, a British company that stirred up racial tensions in South Africa by creating fake social media accounts to promote a racially divisive political campaign on behalf of their client, the wealthy Gupta family, who wanted to draw attention away from their own corrupt dealings in South Africa.73

Beyond the role of the influence industry, the broader ethics of the social media industry must also be considered. “Data colonialism” has been used to describe the way in which Western corporations profit from the commodification of data in the Global South without substantial returns to the users.74 In other words, data are monetized to the disproportionate benefit of Western corporations. That these platforms have been implicated in hate speech that has facilitated genocide raises questions about them being valid spaces for social study.75 The fact that their algorithms disproportionately censor, for example, pro-Palestinian voices also raises questions about “missing data.” And how can we use social media data in a meaningful way without first confronting the ethical dilemmas of studying the discourses either promoted or attenuated by unaccountable big tech corporations?

The nature of academia itself is further cause for caution. Particularly within the neoliberal university, the pursuit of studying the latest zeitgeist, whether social media in 2011 or generative AI in 2024, is a powerful force. Frequently, and especially where corporate tie-ins and grant funding applications demand, such research is encouraged because it is more likely to receive funding. This reality aligns with the increasing fetishization of digital practices and the broader tech industry, inherent in the neoliberal university.76 Again, the context of the neoliberal university prompts the sometimes-uncritical embrace of studying technologies without due care of what that really should, ethically, entail.

The digital age has transformed academic research, particularly in authoritarian and illiberal contexts, creating a complex landscape that blurs traditional boundaries and poses new challenges for researchers. This essay has explored the multifaceted impact of digitality on academia, highlighting forms of spatial, time, and context collapse, and examined the erosion of distinctions between public and private spheres, professional and personal identities, past and present, and even democratic and authoritarian contexts.

The rise of sophisticated surveillance technologies, state-sponsored trolling, and widespread disinformation campaigns has significantly altered the research environment. Researchers now face unprecedented risks to their safety, even when physically removed from their field of study. The integrity of digital data itself has emerged as a pressing concern. The prevalence of bots, inauthentic accounts, and manipulated online discourses should cause us to revisit our epistemological assumptions about social media data. The concept of “authenticity vacuums” introduced above highlights the potential for entire online spaces to be dominated by artificial or coerced narratives, raising profound questions about the veracity or value of digital data in academic research.

There is much that can be done to improve research practices or to mitigate against many of the dilemmas raised here, whether in terms of researcher safety or data integrity. At the very least, researchers need up-to-date and constantly revised digital literacy courses to understand issues that may compromise themselves, their networks, and their data. Research methodologies must evolve to integrate critical analysis of deception supply chains, acknowledging the role of nonstate actors and states in shaping digital discourses. Similarly, the prevalence of elite-driven conversations and “authenticity vacuums” needs to be recognized within methodological trainings ahead of fieldwork. In terms of safety, institutions must provide support systems for researchers dealing with the psychological impacts of online harassment and exposure to distressing digital content. Moreover, institutions should implement robust protocols for responding to transnational digital threats, including providing or facilitating legal and technical support for researchers targeted by malicious actors—states or otherwise.

These challenges are further compounded by the pressures of the neoliberal university system, which often prioritizes impact, visibility, and reputation over the safety and ethical concerns of researchers. The tension between institutional demands and the need for cautious, ethical research practices in digital spaces creates additional dilemmas for academics. As we enter an era increasingly dominated by AI and other emerging technologies, the ability to discern between authentic and inauthentic data, to protect researcher and subject safety, and to maintain the integrity of academic inquiry will be more crucial than ever.