The Effects of Violence on Communities: The Violence Matrix as a Tool for Advancing More Just Policies

In this essay, I illustrate how discussions of the effects of violence on communities are enhanced by the use of a critical framework that links various microvariables with macro-institutional processes. Drawing upon my work on the issue of violent victimization toward African American women and how conventional justice policies have failed to bring effective remedy in situations of extreme danger and degradation, I argue that a broader conceptual framework is required to fully understand the profound and persistent impact that violence has on individuals embedded in communities that are experiencing the most adverse social injustices. I use my work as a case in point to illustrate how complex community dynamics, ineffective institutional responses, and broader societal forces of systemic violence intersect to further the impact of individual victimization. In the end, I argue that understanding the impact of all forms of violence would be better served by a more intersectional and critical interdisciplinary framework.

Rigorous interdisciplinary scholarship, public policy analyses, and the most conscientious popular discourse on the impact of violence point to the deleterious effects that violence has on both individual health and safety and community well-being. Comprehensive justice policy research on topics ranging from gun violence to intimate abuse support the premise that the physical injury, psychological distress, and fear that are typically associated with individual victimization are directly linked to subsequent social isolation, economic instability, erosion of neighborhood networks, group alienation, and mistrust of justice and other institutions. This literature also points to the ways that structural inequality, persistent disadvantages, and structural abandonment are some of the root causes of microlevel violent interactions and at the same time influence how effective macrolevel justice policies are at responding to or preventing violent victimization.1

The most exciting of these analyses have emerged from the subfields of feminist criminology, critical race theory, critical criminology, sociolegal theory, and other social science research that take seriously questions of race and culture, gender and sexuality, ethnic identity and class position, exploring with great interest how these factors influence the prevailing questions upon which practitioners in our field base their practice; questions such as how to increase access to justice, the role of punishment in desistance, the factors that lead to a disproportionate impact of institutional practices, and the perceptions about, and possibilities for, violence prevention and abolitionist practices.2 Discussions about the future of justice policy would be well served by attending to this growing literature and the critical frameworks that are advanced from within it.

In this essay, I will attempt to illustrate how discussions of the effects of violence on communities are enhanced by the use of a critical framework that links various microvariables with macro-institutional processes. Drawing upon my work on the issue of violent victimization toward African American women and how conventional justice policies have failed to bring effective remedy in situations of extreme danger and degradation, I argue that a broader conceptual framework is required to fully understand the profound and persistent impact that violence has on individuals embedded in communities that are experiencing the most adverse social injustices. I use my work as a case in point to illustrate how complex community dynamics, ineffective institutional responses, and broader societal forces of systemic violence intersect to further the impact of individual victimization. In the end, I argue that understanding the impact of all forms of violence would be better served by a more intersectional and critical interdisciplinary framework.

Following a review of the data on violent victimization against African American women, I describe the violence matrix, a conceptual framework that I developed from analyzing data from several research projects on the topic.3 I do so as a way to make concrete my earlier claim: that the effect of violence on communities must be understood from a critical intersectional framework. That is, my central argument here is an epistemological one, suggesting that in the future, the most effective and indeed “just” policies in response to violence necessitate the development of critical far-reaching systemic analysis and social change at multiple levels.

Violent victimization has been established as a major problem in contemporary society, resulting in long-term physical, social, emotional, and economic consequences for people of different racial/ethnic, class, religious, regional, and age groups and identities.4 However, like most social problems, the impact is not equally felt across all subgroups, and even though the rates may be similar, the consequences of violent victimization follow other patterns of social inequality and disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minority groups.5 When impact and consequences are taken into account, it becomes clear that African American women fare among the worst, in part because of the ways that individual experiences are impacted by negative institutional processes.6

While qualitative data suggest that there is a link between social position in a racial hierarchy and Black women’s subsequent vulnerability to violence, the specific mechanism of that relationship has yet to be described or tested.7 However, despite new research that examines the effects of race/ethnicity and gender in combination, there has been a lack of systematic analysis of the intersection of race and gender with a specific focus on the situational factors, cultural dynamics, and neighborhood variables that lead to higher rates and/or more problematic outcomes of violent victimization in the lives of African American women.8

These unanswered questions led to the years of fieldwork that informed the development of the violence matrix. I was interested in broadening the understanding of violence by analyzing the contextual and situational factors that correlate with multiple forms of violent victimization for African American women, incorporating the racial and community dynamics that influence their experiences. I was also concerned about the ways that state-sanctioned violence and systemic oppression contributed to the experience and impact of intimate partner abuse and looked for a way to incorporate “ordinary violence” and “the injustices of everyday life” into an analytic model. I offer this conceptual approach as a potential epistemological model because it proposes to enhance the scientific understanding of violent victimization of African American women by looking at gender and race, micro and macro, individual, community, and societal issues in the same analysis, whereas in most other research, rates of victimization are described either by gender or race, and typically not from within the contexts of household, neighborhood, and society.

More specifically, domestic violence, sexual abuse, and other forms of violence typically understood to be associated with household or familiar relationships are usually studied as a separate phenomenon constituting a gender violence subfield distinct from other forms of victimization that are captured in more general crime statistics.9 The more general research that documents crimes of assault, homicide, and so on does not typically isolate analyses of the nature of the relationship between the perpetrator and the victim, even if it is noted. As a result, gender violence and other forms of violent victimization against women are studied separately, and their causes and consequences, the intervention and prevention strategies, and the needs for policy change are not linked analytically to each other. This leaves unexamined the significant influence of situational factors (such as intimacy) or contextual factors (such as negative images of African American women) on victimization, and on violence more generally.

Prior to describing the violence matrix, readers may benefit from a brief overview of the problems that it was designed to account for. African American women experience disproportionate impacts of violent victimization.10 As the following review of the literature shows, the rates are high and the consequences are severe, firmly establishing the need to focus on this vulnerable group. The goal is not to suggest it is the only population group at risk or that racial/ethnic identity has a causal influence on victimization, but rather to look specifically at how race/ethnicity and gender interact to create significant disproportionality in rates of, perceptions about, and consequences of violence, and to develop an instrument to collect data that can be analyzed conceptually and discussed in terms of contextual particularities.

Assault. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, in 2005, Black women reported experiencing violent victimization at a rate of 25 per 1,000 persons aged twelve years or older.11 In an earlier report, Black women reported experiencing simple assaults at 28.8 per 1,000 persons and serious violent crimes at 22.5 per 1,000 persons, twelve years or older. Black women are also more likely (53 percent) to report violent victimization to the police than their White or male counterparts.12 Situational factors such as income, urban versus suburban residence, perception of street gang membership, and presence of a weapon influence Black women’s violent victimization. Other variables are known to complicate this disproportionality, most notably income, age, neighborhood density, and other crimes in the community like gang-related events. However, few studies note or analyze their covariance. Additionally, reports after 2007 detail statistics on violent victimization for race or gender, but not race and gender; therefore, numbers regarding Black women’s experiences are largely unknown.

Intimate partner violence. Intimate partner violence is a significant and persistent social problem with serious consequences for individual women, their families, and society as a whole.13 The 1996 National Violence Against Women Survey suggested that 1.5 million women in the United States were physically assaulted by an intimate partner each year, while other studies provide much higher estimates.14 For example, the Department of Justice estimates that 5.3 million incidents of violence against a current or former spouse or girlfriend occur annually. Estimates of violence against women in same sex partnerships indicate a similar rate of victimization.15

According to most national studies, African American women are disproportionately represented in the data on physical violence against intimate partners.16 In the Violence Against Women Survey, 25 percent of Black women had experienced abuse from their intimate partner, including “physical violence, sexual violence, threats of violence, economic exploitation, confinement and isolation from social activities, stalking, property destruction, burglary, theft, and homicide.” Rates of severe battering help to spotlight the disproportionate impact of direct physical assaults on Black women by intimate partners: homicide by an intimate partner is the second-leading cause of death for Black women between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five.17 Black women are killed by a spouse at a rate twice that of White women. However, when the intimate partner is a boyfriend or girlfriend, this statistic increases to four times the rate of their White counterparts.18 While the numbers are convincing, they are typically not embedded in an understanding of how situational factors like relationship history, religiosity, or availability of services impact these rates.19

Sexual victimization. When race is considered a variable in some community samples, 7 to 30 percent of all Black women report having been raped as adults, and 14 percent report sexual abuse during their childhood.20 This unusually wide range results from differences in definitions and sampling methods. However, as is true in most research on sexual victimization, it is widely accepted that rape, when self-reported, is underreported, and that Black women tend to underutilize crisis intervention and other supportive services that collect data.21 Even though Black women from all segments of the African American community experience sexual violence, the pattern of vulnerability to rape and sexual assault mirrors that of direct physical assault by intimate partners. The data show that Black women from low-income communities, those with substance abuse problems or mental health concerns, and those in otherwise compromised social positions are most vulnerable to sexual violence from their intimate partners.22 Not only is the incidence of rape higher, but a review of the qualitative research on Black women’s experiences of rape also suggests that Black women are assaulted in more brutal and degrading ways than other women.23 Weapons or objects are more often used, so Black women’s injuries are typically worse than those of other groups of women. Black women are more likely to be raped repeatedly and to experience assaults that involve multiple perpetrators.24

Beyond the physical, and sometimes lethal, consequences, the psychological literature documents the very serious mental health impact of sexual assault by intimate partners. For instance, 31 percent of all rape victims develop rape-related post-traumatic stress disorder.25 Rape victims are three times more likely than nonvictims to experience a major depressive episode in their lives, and they attempt suicide at a rate thirteen times higher than nonvictims. Women who have been raped by a member of their household are ten times more likely to abuse illegal substances or alcohol than women who have not been raped. Black women experience the trauma of sexual abuse and aggression from their intimate partners in particular ways, as studies conducted by psychologists Victoria Banyard, Sandra Graham-Bermann, Carolyn West, and others have discussed.26 It is also important to note the extent to which Black women are exposed to or coerced into participating in sexually exploitative intimate relationships with older men and men who violate commitments of fidelity by having multiple sexual partners.27 Far from infrequent or benign, it can be hypothesized that these experiences serve to socialize young women into relationships characterized by unequal power, and they normalize subservient gender roles for women, although very little empirical research has been done to make this analytical case.

Community harassment. In addition to direct physical and sexual assaults, Black women experience a disproportionate number of unwanted comments, uninvited physical advances, and undesired exposure to pornography in their communities. Almost 75 percent of Black women sampled report some form of sexual harassment in their lifetime, including being forced to live in, work in, attend school in, and even worship in degrading, dangerous, and hostile environments, where the threat of rape, public humiliation, and embarrassment is a defining aspect of their social environment.28 They also experience trauma as a result of witnessing violence in their communities.29

For some women, this sexual harassment escalates to rape. Even when it does not, community harassment creates an environment of fear, apprehension, shame, and anxiety that can be linked to women’s vulnerability to violent victimization. It is important to understand this link because herein lie some of the most significant situational and contextual factors, like the diminished use of support services and reduced social capital on the part of African American women.

Social disenfranchisement. Less well-documented or quantified in the criminological data is the disproportionate harm caused to African American women because of the ways that violent victimization is linked to social disenfranchisement and the discrimination they face in the social sphere. Included here is what other researchers have called coercive control or structural violence.30 The notion of social disenfranchisement goes beyond emotional abuse and psychological manipulation to include the regulation of emotional and social life in the private sphere in ways that are consistent with normative values about gender, race, and class.31 These aspects of violence against African American women in particular are conceptualized in the violence matrix, and include being disrespected by microracial slurs from community members and agency officials, and having their experience of violent victimization denied by community leaders.32 African American women are also disproportionately likely to be poor, rely on public services like welfare, and be under the control of state institutions like prisons, which means that they face discrimination and degradation in these settings at higher rates.33 These situational and contextual factors that cause harm are indirectly related to violent victimization and must be considered part of the environment that disadvantages African American women. From this vantage point, it could be argued that when women experience disadvantages associated with racial and ethnic discrimination, dangerous and degrading situations, and social disenfranchisement, they are more at risk of victimization.34

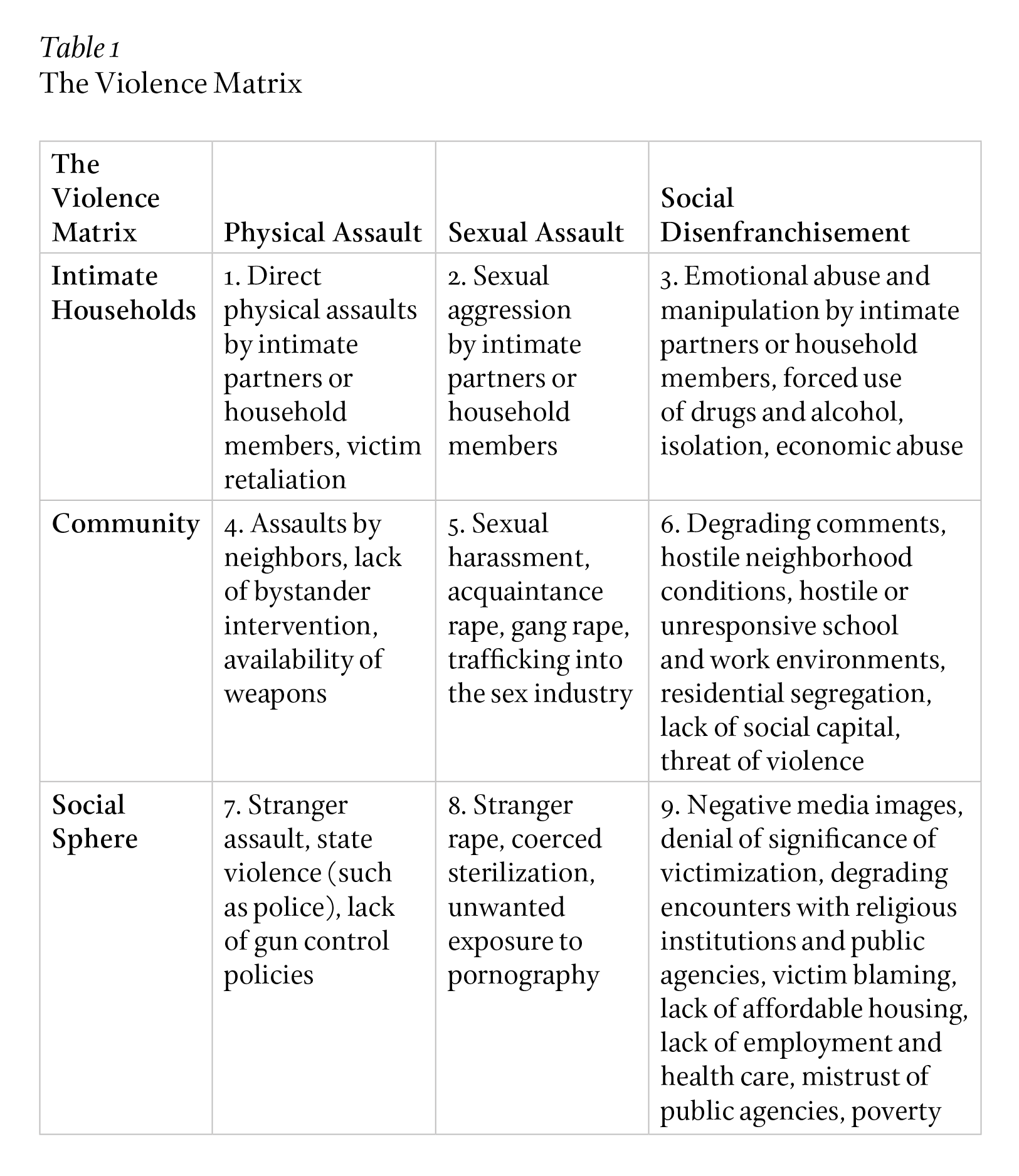

The violence matrix (Table 1) is informed by the data reviewed above and by my interest in bringing a critical feminist criminological approach to the understanding of violent victimization of African American women. It asserts that intimate partner violence is worsened by some of the contextual variables and situational dynamics in their households, communities, and broader social sphere, and vice versa. The tool is not intended to infer causation, but rather to broaden the understanding of the factors that influence violence in order to create justice policy in the future.

The violence matrix conceptualizes the forms of violent victimization that women experience as fitting into three overlapping categories, reflecting a sense that the forms are co-constituted and exist within a larger context and in multiple arenas:35 1) direct physical assault against women; 2) sexual aggressions that range from harassment to rape; and 3) the emotional and structural dimensions of social disenfranchisement that characterize the lives of some African American women and leave them vulnerable to abuse. Embedded in the discussion of social disenfranchisement are issues related to social inequality, systemic abuse, and state violence.

Consistent with ecological models of other social problems, the violence matrix shows that various forms of violent victimization happen in several contexts and are influenced by several variables.36 First, violence occurs within households, including abuse from intimate partners as well as other family members and coresidents. Dynamics associated with household composition, relationship history, and patterns of household functioning can be isolated for consideration in this context. The second sphere is the community in which women live: the neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, and public spaces where women routinely interact with peers and other people. This context has both a geographic and a cultural meaning. Community, in this context, is where women share a sense of belonging and physical space. An analysis of the community context focuses attention on issues like neighborhood social class, degree of social cohesion, and presence or absence of social services. The third is the social sphere, where legal processes, institutional policies, ineffective justice policies, and the nature of social conditions (such as population density, neighborhood disorder, patterns of incarceration, and other macrovariables) create conditions that cause harm to women and other victims of violence.37 The harm caused by victimization in this context happens either through passive victimization (as in the case of bystanders not responding to calls for help because of the low priority put on women’s safety) or active aggression (as in police use of excessive force in certain neighborhoods) that create structural disadvantage.38

The analytic advantage of using a tool like the violence matrix to explain violent victimization is that it offers a way to move beyond statistical analyses of disproportionality to focus on a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between contextual factors that disadvantage African American women and the situational variables leading to violent victimization. Two important features of this conceptual framework allow for this. First, the violence matrix theoretical model considers both the forms and the contexts as dialectical and reinforcing (as opposed to discrete) categories of experience. Boundaries overlap, relationships shift over time, and situations change. It helps to show how gender violence and other forms of violent victimization intersect and reinforce each other. For example, sexual abuse has a physical component, community members move in and become intimate partners, and sexual harassment is sometimes a part of how institutions respond to victims. This theoretical model examines the simultaneity of forms and contexts, a feature that most paradigms do not have.39 The possibility that gender violence (like marital rape) could be correlated with violence at the community level (like assault by a neighbor) holds important potential for a deeper understanding of violent victimization of vulnerable groups and therefore informs the future of justice policy.

A second distinguishing feature of this conceptual model is that it broadens the discussion about violent victimization beyond direct assaults within the household (Table 1, cells 1 and 2) and sexual assaults by acquaintances and strangers (cells 5 and 8), which are the focus of the majority of the research on violence against women. It includes social disenfranchisement as a form of violence and social sphere as a context (cells 3, 6, 7, 8, and 9). In this way, the violence matrix focuses specific attention on contextual and situational vulnerabilities in addition to the physical ones. More generally, this advantages research and justice praxis. This approach responds to the entrenched problem of gender violence as it relates to issues of structural racism and other forms of systematic advantage. Models like this therefore hold the potential to inform justice policy that is more comprehensive, more effective, and, ultimately, more “just.”

My hope is that the violence matrix will deepen the understanding of the specific problem of violence in the lives of Black women and serve as a model for intersectional analyses of other groups and their experiences of violence. I hope it points to the utility of moving beyond quantitative studies and single-dimension qualitative analyses of the impact of violence and instead encourages designing conceptual models that consider root causes and the ways that systemic factors complicate its impact. This would offer an opportunity for a deeper discussion around violence policy, one that would include attention to individual harm, and how it is created by, reinforced by, or worsened by structural forms of violence. It would bring neighborhood dynamics into the analytical framework and engage issues of improving community efficacy and reversing structural abandonment in considerations of potential options. Questions about where strategies of community development and how the politics of prison abolition might appear would become relevant. And in the end, it would advance critical justice frameworks that answer questions about what 1) we might invest in to keep individuals safe; 2) how we might help neighborhoods thrive; and 3) how we might create structural changes that shift power in our society such that violence and victimization are minimized. More than rhetorical questions and naively optimistic strategies, these are real issues that must inform any discussion of the future of justice policy. A model like the violence matrix, modified and improved upon by discussions at convenings like those hosted by the Square One Project, offer some insights into both the what and the how of future justice policy. I hope that this essay is helpful in moving that discussion forward.