Fighting Violence Against Women: Laws, Norms & Challenges Ahead

In the 1990s and 2000s, pressure from feminist movements and allies succeeded in pushing scores of states to reform their laws to prevent and punish violence against women (VAW). Even in states with progressive legislation, however, activists face challenges to induce citizens to comply with the law, compel state authorities to enforce the law, and ensure the adequate allocation of resources for social support services. In this essay, we take stock of legislative developments related to VAW around the world, with a focus on the variation in approaches toward intimate partner violence and sexual harassment. We analyze efforts to align behavior with progressive legislation, and end with a discussion of the balance activists must strike between fighting VAW aggressively with the carceral and social support dimensions of state power, while exercising some restraint to avoid the potentially counterproductive effects of state action.

Until quite recently, states took little action to combat violence against women (VAW), a comprehensive concept encompassing diverse phenomena including rape, intimate partner violence, trafficking, honor killings, and female genital mutilation. In fact, most states endorsed many types of violence, for example through laws stating that sex was a marital obligation, that rapists could escape charges by marrying victims, that parents could marry off their girl children, or that men who murdered adulterous wives were merely “defending honor.” The diverse phenomena we today call VAW was hardly recognized as a crime, let alone as a fundamental question of human rights.

Feminists began to use the VAW concept in the 1960s and 1970s as they probed how women’s unequal social position enables sexual and gender violence. In 1993, the global community framed VAW as a question of human rights and as a manifestation of gender subordination in the Vienna Declaration of the World Conference on Human Rights. Today, this connection between VAW, human rights, and women’s status is well established in international law and global discourses of democratic legitimacy. By signing on to international conventions and agreements such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Vienna Declaration, the Inter-American Convention on Violence against Women, the Maputo Protocol, the Beijing Platform for Action, and the Istanbul Convention, most states have committed to adhere to these norms, at least rhetorically.

In the 1990s and 2000s, pressure from feminist movements and allies succeeded in pushing scores of states to reform their laws to ban violent practices against women and girls. Many states adopted specialized legislation, first to prevent and punish domestic violence, and then later to combat a broader range of violent and harassing practices. Often, however, laws look good on paper but violence and harassment remain common. The major challenge is to align behavior with the letter and spirit of progressive legislation.

In this essay, we take stock of legislative developments around the world and the variation in approaches toward intimate partner violence and sexual harassment. Dozens of states still resist the demands of feminist activists and refuse to conform to international standards on violence against women. However, even in states with progressive legislation, activists face challenges to induce citizens to comply with the law, compel state authorities to enforce the law, and ensure the adequate allocation of resources for social support services. We conclude with a discussion of how activists must strike a balance between fighting VAW aggressively with the carceral and social support dimensions of state power, while exercising restraint to avoid overreaching in ways that produce counterproductive effects, such as the revictimization of women and the violation of other rights.

Sexual and gender violence and harassment are widespread. Worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 35 percent of women have experienced sexual or domestic violence. In Mexico, the ENDIREH survey (National Survey on the Dynamics of Household Relationships) of more than 140,000 households in 2016 found that some 16 percent of women in a relationship had experienced serious physical violence at the hands of their current partner. Over 80 percent of women parliamentarians surveyed in thirty-nine countries say they suffered harassment. In universities in the United States, between 11 percent and 25 percent of women students report experiences of sexual assault. Across the MENA region, 40 percent to 60 percent of women say they have been harassed on the street, while 30 percent to 65 percent of men report having perpetrated such acts.1

The theoretical development of the VAW concept has enabled scholars, activists, and policy-makers around the world to develop policies and analyze behavior related to violence in multiple ways.

First, activists’ elaboration of the mechanisms needed to fight VAW, ranging from specialized legislation to support services and administrative coordination, has enabled scholars to operationalize and measure multiple policy changes. We now have access to a large amount of data about efforts to combat VAW. The World Bank’s Women, Business, and the Law (WBL) data set, which we use in this essay, contains four waves of data from across the world on laws in multiple areas of legislation related to gender and sexual violence.2 The OECD’s Social Institutions and Gender Index’s physical integrity ranking orders countries according to the comprehensiveness of their approach toward intimate partner violence, rape, and sexual harassment.3 The Womanstats database has scales on the scope and depth of national legislation on domestic violence, rape (including marital rape and date rape), and honor killings, as well as indicators of social practice in all of these areas, up until 2017 and 2018.4 The Htun-Weldon data set contains four decades of comprehensive data on state approaches to VAW, encompassing domestic violence, rape, and sexual harassment legislation, services to victims and vulnerable groups of women, and policies such as training, public awareness campaigns, and administrative coordination.5

Such data sets make it easier to evaluate governments’ approaches to VAW and to assess whether or not a state is attempting seriously to combat the problem. The fact that the data sets disaggregate types of VAW also allows insights into how changes may be taking place in some arenas but not in others. A challenge with these data, however, is that such large, cross-national databases usually do not include information on within-country differences in approaches and implementation, which may be significant in places with pronounced socioeconomic inequalities–driven, for example, by urban-rural divides–or the application of customary or religious laws.

Second, activists’ expansion of the VAW concept to include multiple forms of violence has identified the range of behaviors–including not just rape and physical battery, but also stalking, psychological violence, female genital mutilation, harassment, forced pregnancy testing, and more–that need to be measured to assess the prevalence of VAW. However, it is difficult to gather statistics on these experiences. Episodes of violence and harassment are notoriously underreported, which makes official crime and police data a poor reflection of actual behavior. In fact, official data may be misleading, as more women tend to report violence as norms change and they feel more empowered.

Our best estimates of the incidence of VAW thus come from household surveys that probe respondents’ experiences. The most sophisticated of these surveys ask about experiences across types of violence and in multiple spheres, such as at home and at work, on the street, with family members and with strangers, in the past year and over the course of a lifetime. Surveys with large sample sizes permit us to get a comprehensive overview of the experiences of differently situated women. Yet there are challenges with such data, too: they are often not comparable across studies and countries due to differences in definitions of violence, questions asked, and survey methodology. Even within the same study, scholars have found “interviewer effects,” with different response patterns according to the gender of the interviewer and whether or not another person is present during the interview.

Finally, activists and scholars have long argued that VAW is attributable not only to individual-level factors such as aggression, alcohol and drug use, or family history, but also to cultural attitudes and social norms that legitimize violent behavior, and above all to the gender structure of society, which tends to subordinate women and render them vulnerable to men’s economic and social power. Using opinion surveys and other tools, therefore, we can measure and evaluate social contexts that enable violence and impunity.

Evidence from around the world, for example, demonstrates a strong association between norms and attitudes condoning male authority and endorsing wife beating and the perpetration of violence. Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted by the U.S. Agency for International Development reveals that in thirty Sub-Saharan African countries, a majority of women respondents say that it is acceptable for a man to beat his wife for various reasons, including if she argues with him, refuses to have sex, or burns food. Geographic variation in attitudes closely corresponds to experiences of violence. In Nepal, perceptions that prevailing social norms endorse male dominance, value family honor, and accept violence are related to women’s experiences of physical and sexual intimate partner violence. In Mexico, women who say that violence belongs in the family–more than one-quarter of a large national sample–are more likely to be victims of violence, and also less likely to report such incidents.6

In this essay, our empirical focus is primarily on domestic violence and sexual harassment. These issues do not exhaust the range of the VAW phenomenon, which is far broader, but are arguably the issues that activists have struggled hardest to change beliefs about. It is rare today to find people who defend forms of violence against women such as gang rape, honor killings, and female genital mutilation, though defenders do exist in some places. By contrast, as we mentioned earlier, large numbers of people hold on to attitudes that explicitly or implicitly condone intimate partner violence and sexual harassment.

Even as dysfunctional beliefs persist, feminist activists, often allied with women politicians and human rights movements, have compelled states to take action to combat violence. Progressive VAW laws, especially when adopted by authoritarian and otherwise conservative regimes, are subject to criticism as parchment institutions intended to look good abroad and placate critics at home. Still, even when not fully enforced or implemented, VAW laws uphold aspirational rights that signal consensus and state commitment. By codifying a plan for aggressive state action, the laws lend support and legitimacy to feminist efforts to change social norms and empower women.7

The World Bank’s Women, Business, and the Law data show that most countries have taken some action on domestic violence.8 The most comprehensive laws specify that domestic violence is a crime, create mechanisms to investigate and punish perpetrators, and offer resources and protection to victims, such as restraining orders, shelters, hotlines, and legal assistance. Many laws also provide training for police, judges, social workers, and health care professionals, as well as social marketing campaigns to change norms and encourage women to report violence and seek help.

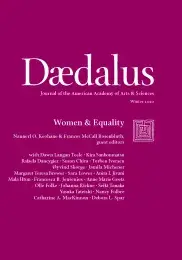

According to the WBL data from 2018, a large majority of countries (144 out of the 189 included) have adopted specialized laws on domestic violence.9 As we can see in Figure 1, this includes most countries in Europe and in the Americas, as well as a large number of countries in the southern parts of Africa and Asia. A smaller group of countries–Belgium, Canada, Chad, Djibouti, Estonia, Libya, Madagascar, Morocco, and Tunisia–lacks specialized legislation about domestic violence, but includes aggravated penalties in the criminal law for violence against spouses and other family members. A third group of thirty-six countries–mostly in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East–has no legal mechanisms that seriously address domestic violence.10

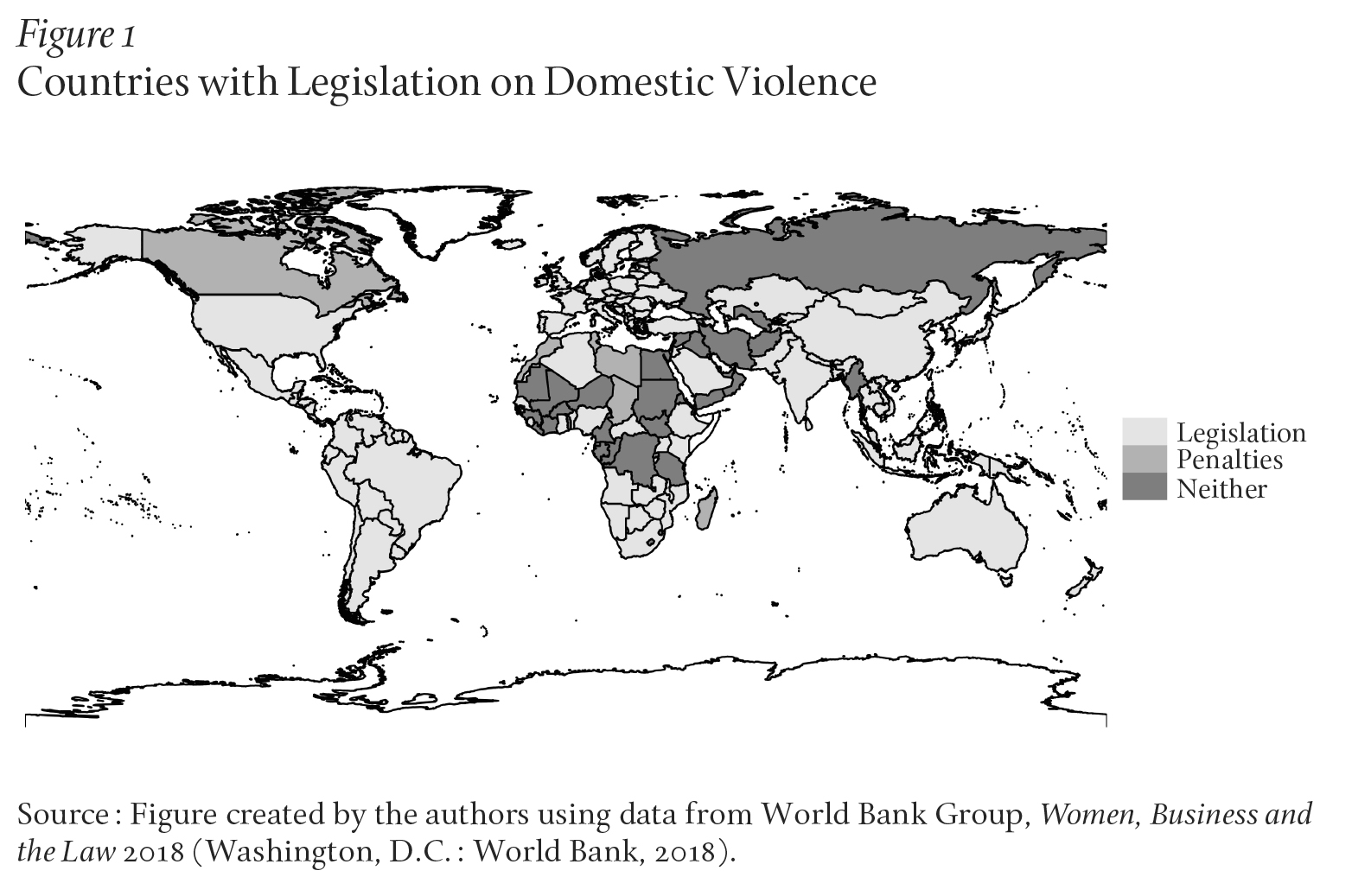

Domestic violence laws vary in their degree of comprehensiveness, depending on the timing of their adoption and national discourses on violence. For example, Figure 2 shows that almost all countries with domestic violence legislation recognize both physical violence and psychological violence.11 In addition, many countries acknowledge sexual violence (119 countries, including 82.6 percent of the countries with specialized domestic violence legislation) and economic violence (95 countries, 66 percent of the countries with specialized legislation).

An important part of sexual domestic violence is marital rape. Feminists worldwide have struggled for decades to get the concept of marital rape recognized. Opposition to the marital rape concept derives from two patriarchal principles: that sex is an obligation of marriage and that women must do what their husbands say. Even in contexts in which there is broad agreement that domestic violence is wrong, some social actors reject the idea that nonconsensual sex in marriage is rape. In discussions over a violence against women law in Myanmar in the 2010s, for example, multiple groups reportedly opposed criminalizing marital rape, including women officials from the National Committee for Women’s Affairs.12

Marital rape is a widespread problem: in the United Kingdom, for instance, the National Health Service estimates that about 45 percent of all rape is committed by current partners. In a survey of 9,200 Indian men conducted by United Nations Population Fund, about one-third of the respondents said they had forced a sexual act on their wives. Without laws that explicitly criminalize marital rape, the practice is subject to legal interpretation and contestation, and it is easier for people to continue thinking it is not a serious crime. In Norway, for example, the criminal code does not explicitly mention marital rape, and, historically, rape within a marriage was not considered a crime. In fact, it was not until 1974 that a man was condemned for raping his wife.13

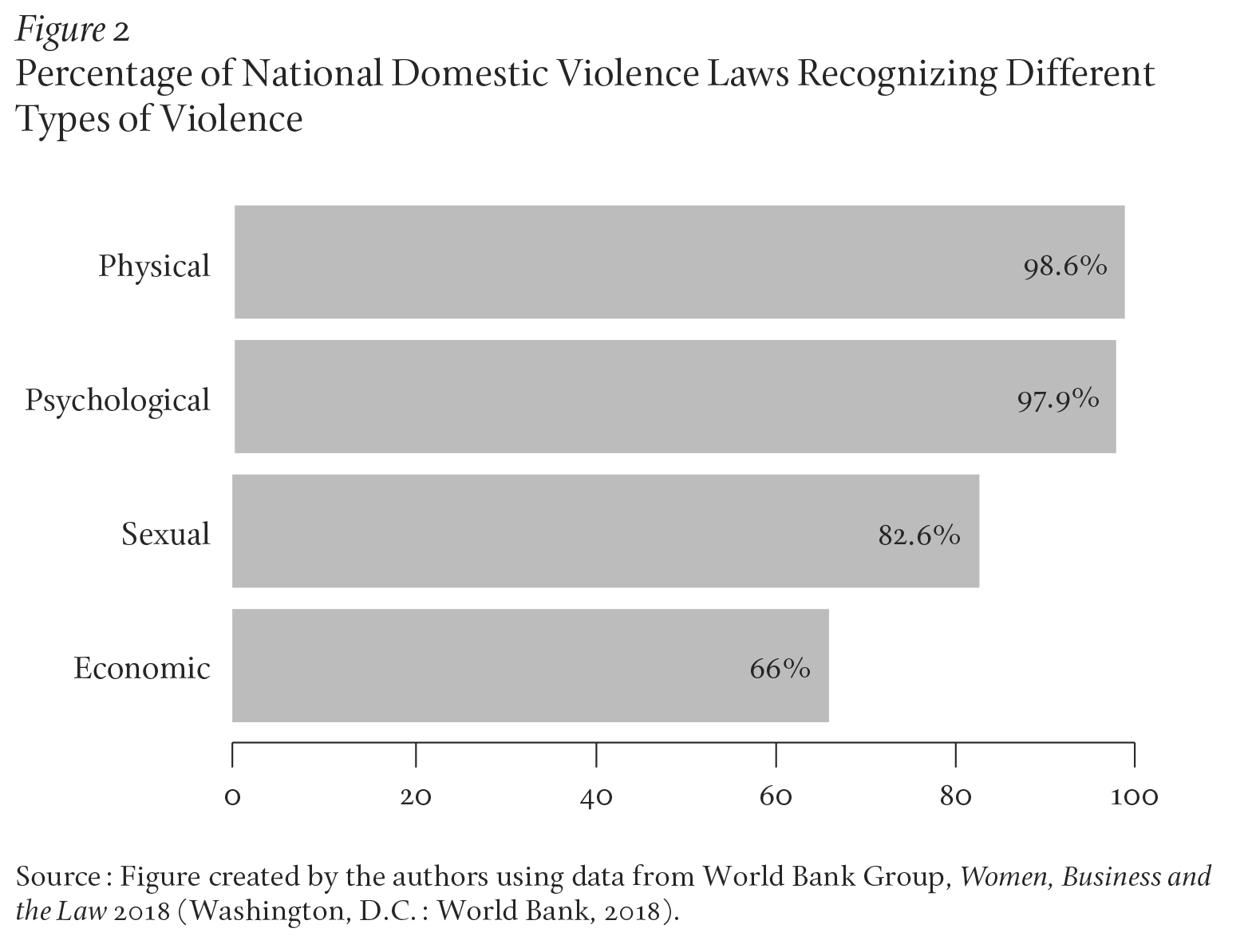

Figure 3 shows that some seventy-eight of the 189 countries (41 percent) in the WBL dataset have legislation that explicitly criminalizes marital rape, including Australia, Canada, France, and Sweden, as well as most of the countries in Latin and Central America and some countries in the southern part of Africa. In another seventy-seven countries (41 percent)–including the United States, most European countries, as well as a large share of the countries in Africa and Asia–a woman can file criminal charges against her husband in the case of marital rape.

In the remaining thirty-four countries (18 percent)–mostly in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia–married women have no legal protection against marital rape and social actors continue to contest the concept. In India, for example, the 1860 Penal Code states explicitly that sexual coercion in marriage does not amount to rape. In 2013, parliament reformed the law to criminalize marital rape, but only if the wife is under fifteen years old. Then, the Supreme Court ruled in 2017 that it is unconstitutional to permit the marital rape of minors between the ages of fifteen and eighteen, thereby enabling wives younger than eighteen to allege marital rape. In 2018, a justice in the Gujarat High Court ruled that a man who had repeatedly raped his wife was guilty of sexual harassment and spousal cruelty, but not rape due to the spousal exception. In a move heralded by activists, the justice called for the nationwide criminalization of marital rape regardless of age.

A different, though related, topic is whether countries exempt rapists from criminal penalties if they marry their victims. Though most societies have reformed laws to remove these marriage provisions, a stubborn group has not, including Angola, Bahrain, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, the Philippines, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, and the West Bank and Gaza.

Another major issue on the agenda for women’s rights activists is sexual harassment, which encompasses sexual coercion, unwanted sexual advances, and gender harassment. In the past few decades, feminist demands have compelled states to take action against sexual harassment in the workplace, schools, public institutions, and common spaces.

Some countries, such as the United States, expanded legal understandings of sex discrimination to encompass sexual harassment. Many European countries broadened labor protections to cover sexual coercion, gender harassment, and bullying in the workplace. In yet other contexts, laws intended to combat gender and sexual violence incorporated harassing behavior. For example, Mexico’s 2007 federal law, which guarantees women a “life free from violence,” purports to combat various forms of violence including psychological, physical, economic, patrimonial, sexual, and other violence intended to “harm women’s dignity, integrity, or liberty.”14

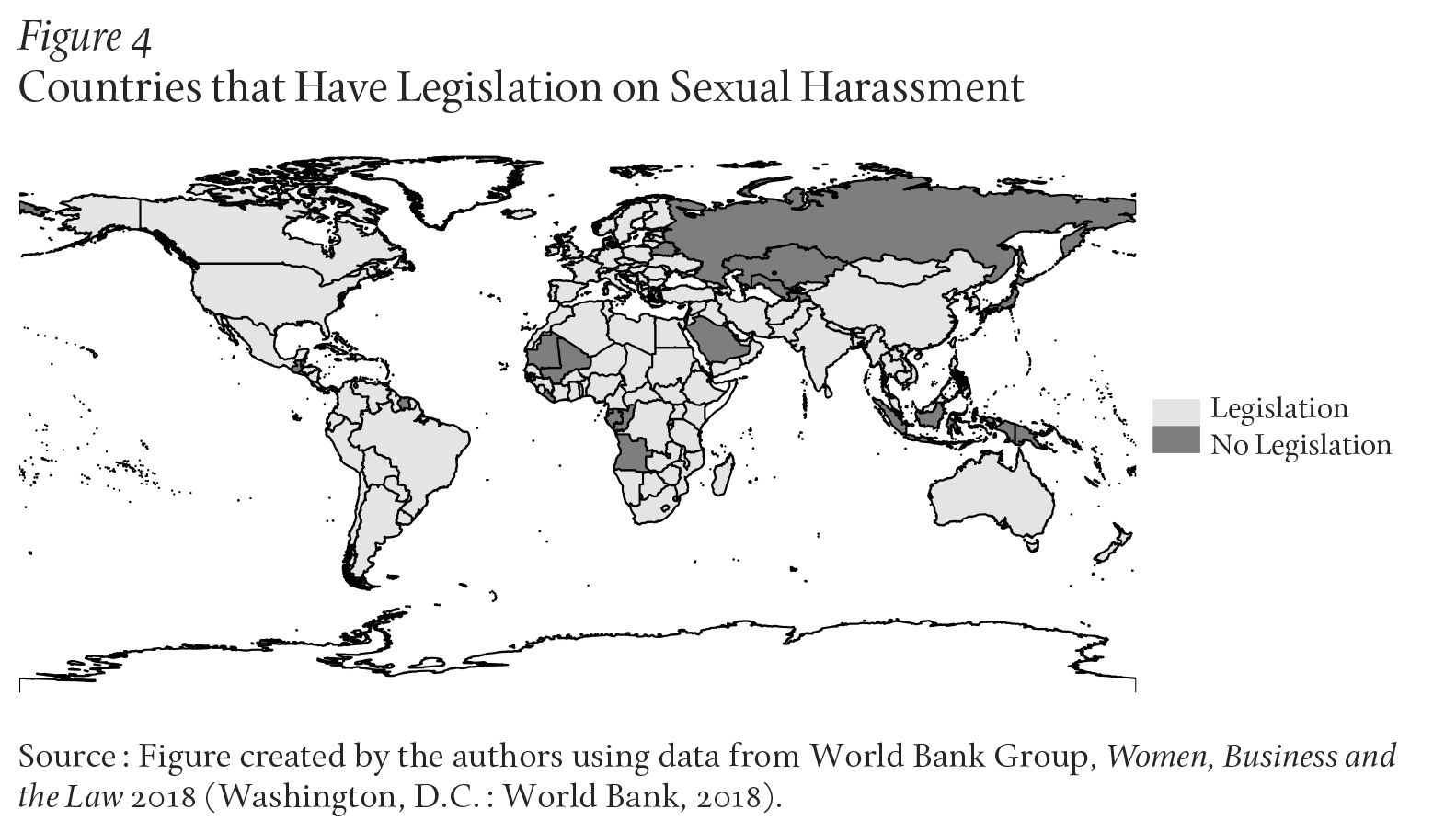

Figure 4 identifies the 154 countries in the world that have adopted legislation against some form of sexual harassment as of 2018.15 Only a minority of countries lacks any legislation, including large countries such as Russia, Japan, and Indonesia, as well as several countries in Africa and the Middle East, including Angola, Liberia, and Saudi Arabia.

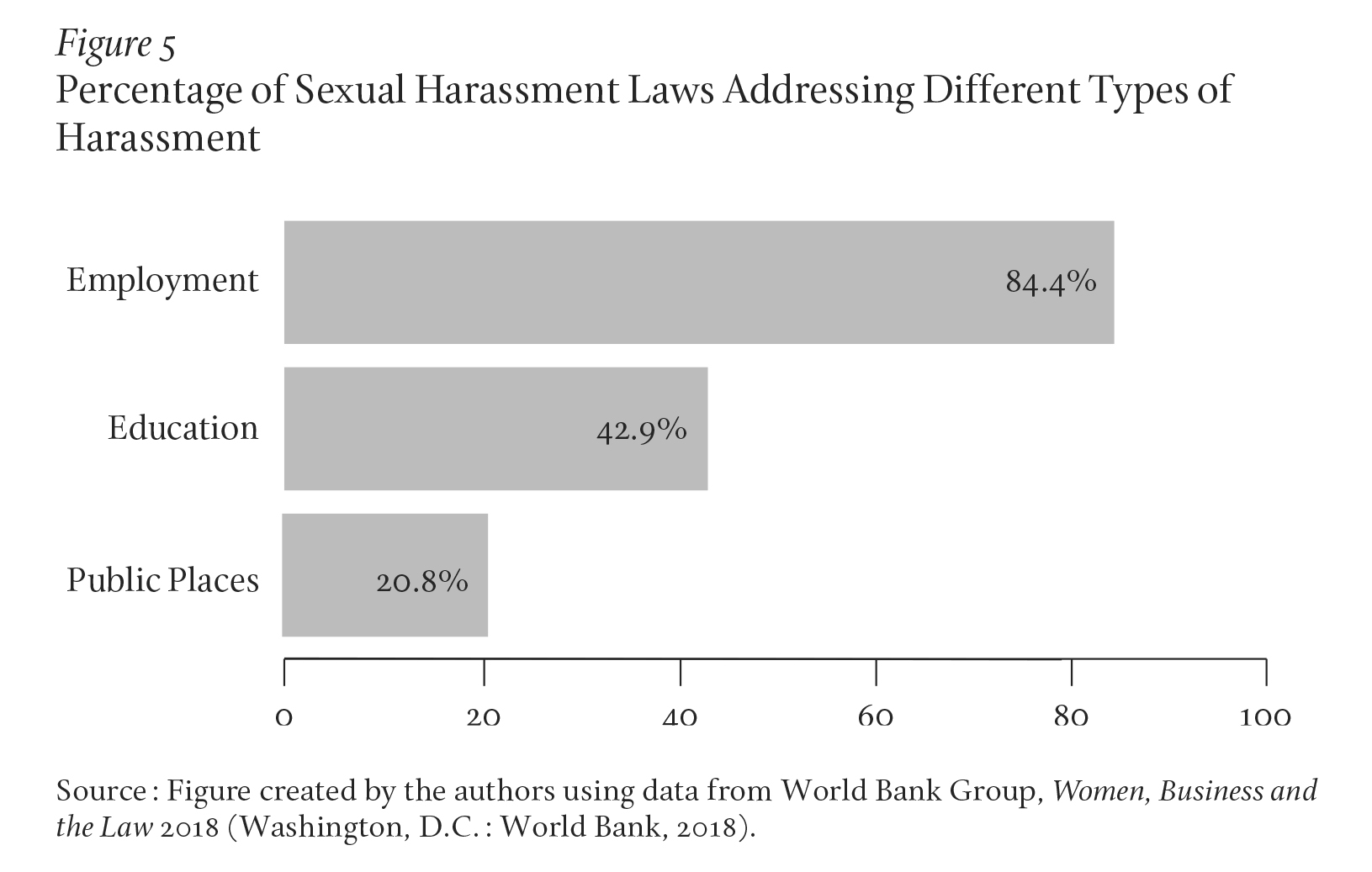

However, laws vary considerably in the domains they apply to (see Figure 5). In 130 countries (84.4 percent), sexual harassment legislation covers harassment in employment, though criminal penalties are stipulated in only seventy-nine of these countries. In sixty-six countries (42.9 percent), sexual harassment legislation addresses educational contexts. In only thirty-two countries (20.8 percent) does the law cover sexual harassment in public spaces.

Even when the law does not explicitly address a particular form of sexual harassment, it may still be possible to challenge harassing behavior in court. As in the case of domestic violence discussed earlier, however, the failure explicitly to typify proscribed behaviors may make it harder to get authorities, peers, colleagues, and family members to take women’s grievances seriously and to respond appropriately. Gender harassment, for example, tends to be far more pervasive than sexualized advances and sexual coercion in U.S. workplaces, and frequently just as detrimental to women’s health, their careers, and organizational climates. Yet gender harassment often skirts below the legal radar, and some evidence suggests that gender harassment, but not other forms of sexual harassment, has increased since the #MeToo movement.16

The existence of laws criminalizing domestic violence and sexual harassment does not mean that people comply or that state authorities enforce them. The letter of the law in many places is far more progressive than social norms and individual attitudes, which implies that behavioral alignment with the law is a primary challenge facing VAW activists today.

As we mentioned earlier, studies show that the problem of violence against women persists across social groups and contexts, even in countries where laws combatting VAW are decades old. What is more, only a small share of women who experience violence or harassment report this to the authorities. Analysis of DHS surveys in twenty-four countries finds that the average share of women victims who report gender-based violence to public institutions is 7 percent, though a larger share (40 percent) say they spoke with family or friends about their experiences.17

Reluctance to report is attributable partially to attitudes that see violence as normal, common, and a private or family matter. Underreporting may also be strategic, as women choose to avoid emotional, financial, and personal risks associated with police intervention and legal proceedings. Women who report incur costs, including disbelief and demeaning treatment by the authorities, retaliation, and ostracism by family and community. Forty-five percent of the approximately ninety thousand charges of discrimination made to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2015 included a complaint of retaliation (and those are the reported incidents!).18

High attrition rates for VAW cases increase reporting risks faced by women. Across much of the world, legal authorities end up prosecuting very few allegations of domestic and sexual violence. Women often drop charges. In the rare event that a case of rape or domestic violence goes to court, judges and prosecutors often question victims about their morality and sexual practices. Convictions are rare. In fact, in most European countries, reporting rates have increased, but conviction rates have actually fallen.19

Governments, international organizations, and civil society groups around the world have adopted a range of interventions to change social norms, make it easier and safer for victims to report, and encourage bystanders to intervene to stop violence. Many groups focus on social norms marketing via the mass media, which are less costly and easier to implement than improvements in government services and infrastructure or person-to-person training. A large campaign in Uganda, for example, involves showing videos depicting the consequences of intimate partner violence and modeling bystander interventions during village film festivals. Follow-up studies find that, among people who had seen the videos, there was a greater tendency to report abuse and some reduction in experiences of violence, even as attitudes endorsing violence did not change.20

Every normative intervention, however, runs the risk of producing unintended consequences. For example, it is common for gender violence campaigns to emphasize the prevalence of violations–for example, with billboards stating that half of women are victims of intimate partner violence–in order to elicit outrage and mobilize a commitment to change. Yet social psychologists’ research implies that such campaigns may promote complicity with existing trends by increasing people’s awareness of what is actually typical in their community.21

In the United States, a vast majority of companies and universities require that workers and students participate in trainings intended to prevent sexual misconduct. Trainings typically cover federal law, organizational policies, and reporting procedures; many also seek to communicate principles of equality and affirmative consent. Yet a growing body of evidence has shown that training, though well intentioned, frequently backfires. Studies show that some men have adverse reactions to training, growing more extreme in sexist views and in their proclivity to harass; that people’s embrace of traditional gender stereotypes increases; and that women say they are less likely to report assault. In U.S. corporations, employee training programs have led to fewer women rising to management ranks.22

More effective interventions against sexual assault and harassment involve leaders and influential social referents as change agents. Programs aiming to alter community norms and empower bystanders to intervene to stop assault and harassment have produced good results. Bystander intervention training, for example, has been linked to behavioral and attitudinal changes as well as a reduction in rates of assault on college campuses and in the U.S. military.23

A key remaining challenge for women’s rights activists and their supporters, particularly in the Global North where wide consensus exists about the most serious forms of VAW, is to find the right balance between using and restraining state power. Almost everyone wants violence and harassment to be taken more seriously, and we are far from a situation in which prisons are packed with rapists and harassers. Yet there is a risk that campaigns against sexual misconduct may strengthen the carceral state, produce unintended consequences such as reduced reporting and exclusion of women, and infringe on other important rights.

How hard should society punish acts of violence against women? Some studies show that tougher sentences and longer prison terms help to deter serial perpetrators, but many activists object to using the criminal justice system and mechanisms of policing, prosecution, and incarceration to fight gender and sexual violence. So-called carceral feminism and its instruments, such as mandatory arrest laws, may empower law enforcement authorities at the expense of individual women, particularly intersectionally disadvantaged groups of women. As a result, women may be more likely to suffer revictimization by police and prosecutors, and minority communities may experience biased treatment. In addition, carceral feminism runs the risk of diverting attention from structural conditions conducive to gender violence, such as social inequalities and the concentration of economic and political power in men’s hands.24

A related issue is how expansively violence, assault, and harassment should be defined. It is crucial to recognize the multiple ways that women are violated and to enforce legislation that punishes serious crimes. But many human encounters are ambiguous. Laws that draw clear lines in these gray areas, and that authorize official scrutiny of intimate relations, may lead to unintended results.

For example, laws in several U.S. states, and policies in many hundreds of universities and colleges, apply the “affirmative consent” standard to define sexual assault. All participants in a sexual interaction must explicitly express their consent at each stage, or one or more have assaulted the other(s). In order to clarify misunderstandings, the standard classifies a great deal of behavior as assault, with potentially severe penalties for the perpetrator. Critics, including prominent feminists and legal scholars, have raised concerns that the affirmative consent standard is unenforceable, violates the presumption of innocence and due process rights of the accused, and fails to address the underlying causes of assault, which include gender hierarchies pervading the “hookup culture.”25 Our own field experiments on the effects of mandatory sexual misconduct training on a university campus suggest that emphasizing affirmative consent may make women less likely to report an incident of sexual harassment or assault.26

Enhanced surveillance of everyday behavior for patterns of sexual misconduct may lead some men simply to avoid interactions with women. Recent U.S. surveys show that around half of male managers are afraid to work with women colleagues, and that the number afraid to mentor women has tripled since the rise of the #MeToo movement. Afraid that casual comments and jokes will be misconstrued as harassment, more men endorse the “Mike Pence rule” of not having dinner with any woman except their own wife.27 As a result, more women may end up excluded from professional networks.

Ultimately, the broad characterization of VAW has advantages and disadvantages. We have a more precise understanding of the range of phenomena that harm women’s dignity and limit their opportunities. But such an enhanced understanding does not imply that we are able to engineer precise interventions. Our legal categories and policy tools are still too blunt to eliminate VAW from the top down. Individual women and local communities, when they have access to resources and bargaining power, may be able to more consistently impose costs to deter perpetrators and generate new norms than the criminal justice hand of the state.

Many states have made dramatic progress to combat violence against women, at least on paper. Some countries remain stubborn, refusing to recognize the possibility of marital rape, sexual harassment, or resisting a comprehensive approach to domestic violence. Even in countries with progressive legislation, law-practice gaps remain. As some powerful men go down on allegations of harassment, millions of ordinary women endure it. Yet to a much greater extent than in the past, society is mobilized against extreme forms of violence and the problem of impunity, and international organizations and civil society groups test interventions to change social norms and attitudes, encourage reporting, and reduce perpetration.

Global efforts to end VAW are impressive and important. The ongoing challenge, particularly in the Global North, is to strike a good balance between aggressive state action against violent behavior and state restraint to enable the unfolding of social processes that generate legitimate norms and empower women. The state enforces right and wrong, but many states are weak and state actors have conflicting motives. Even strong states cannot engineer social change completely. State-sponsored projects have the potential to produce unintended and unfortunate consequences, such as reducing women’s autonomy.

Combating violence requires attention to beliefs and norms and above all to power asymmetries that render women vulnerable to abuse. Women need a firm structural foundation–resources, land, jobs, social support–to contest, and to exit from, violence and harassment in their daily lives. Many studies show that women with access to resources are better able to leave abusers and bargain for more equitable treatment in marriage. Reforming discriminatory family laws that subordinate women to male guardians, and limit their ability to work, manage, and inherit property, will contribute to reducing violence. Social policies that alleviate the financial penalties of divorce and single motherhood, combat discrimination in the workplace, and enable women to combine mothering and wage work are also essential.28 Empowered women are the key to ending gender and sexual violence.

AUTHORS’ NOTE

This research was conducted with support from the Andrew Carnegie Fellows Program and the Norwegian Research Council (project number 250753). Replication data and code can be accessed at www.francesca.no.