Picasso’s “Guernica”

Look: where round the wide horizon

Many a million-peopled city

Vomits smoke in the bright air

Mark that outcry of despair!. ..

Look again, the flames almost

To a glow-worm's lamp have dwindled:

The survivors round the embers

Gather in dread.

Shelley, “Prometheus Unbound” (1818)

Great artists by some hidden direction assemble where life is most intense, where a new world is about to be born:

In the fifteenth century: Florence and Flanders.

In the sixteenth: Venice.

In the seventeenth: Amsterdam.

Afterward: Paris.

From 1910 to 1920: Moscow (Chagall, Gabo, Kandinsky, Malewitch, Pevsner, Tatlin).

They come together to shape a new world. With the technique taken from their predecessors they create a new form.

More modest talents also are often attracted; they are inspired not by the turbulent life around, but by the work of greater artists, forerunners and contemporaries. They adapt to the taste of the public what in the creations of genius seems strange and abhorrent; they form a school.

Genius is inspired by life—talent, by art. Genius shocks—talent smooths.

In the beginning of the century Picasso and Braque come to Paris. In 1907 they meet. During a few years of daily contact they transform reality, give it a new shape—not the reality they see with the eye but the reality of the mind.

We see a rectangular table in perspective—that is, as a trapezium; our side of the table looks more important than the other side. But we know the table to be a pure rectangle.

The camera sees only one side of our face, but we know it to be in profile and en face at the same time.

Picasso and Braque quit visual reality and start to paint the environing objects as they know they are. The table top becomes a rectangle again, and the human face is rendered from the side and the front at the same time. This decisive act we call Cubism.

About 1500 the artists of the Renaissance invented the perspective we are still accustomed to: the artist sat down on his chair, looked at the scene from one definite angle, and tried to fix it on his panel accordingly.

Now after four hundred years the painter rises from his chair, starts moving around his object, and tries to render the totality. He changes his point of view. Cubism is: Welt-an-Schauung. Cubism concerns our intellect, not our heart—that is left to Expressionism.

For three decades Picasso investigates the field of form. His researches are laid down in a long series of masterpieces. Again and again he startles us with new discoveries.

Paris 1937: Every nation prepares its contribution to the world fair. The Spanish Government, assailed by Franco and his blood-stained friends, decides to demonstrate its love for freedom and humanity in a pure and simple building. It commissions a few great artists to express their ideas. It is to be not a commercial pavillon, but a home for democracy.

Sert becomes the architect, Miró and Picasso are invited to paint great frescoes, Calder creates his famous fountain of Mercury. Gonzales forges "La Montserrat." The long wall near the entrance is given to Picasso. In January the artist starts making sketches, but inspiration fails. Months pass by. The battle for freedom goes on. Picasso hesitates. The Civil War had only inspired him to a few sarcastic etchings, of which “Songes et Mensonges de Franco” are the most widely known.

Then, on 28 April, Guernica, the holy city of the Basques, is destroyed in an air raid. Men, women, children, and cattle die miserably amid smoking ruins. An outcry of indignation shakes the world, but only a few realize that Guernica is merely the prelude to slaughter on a much larger scale.

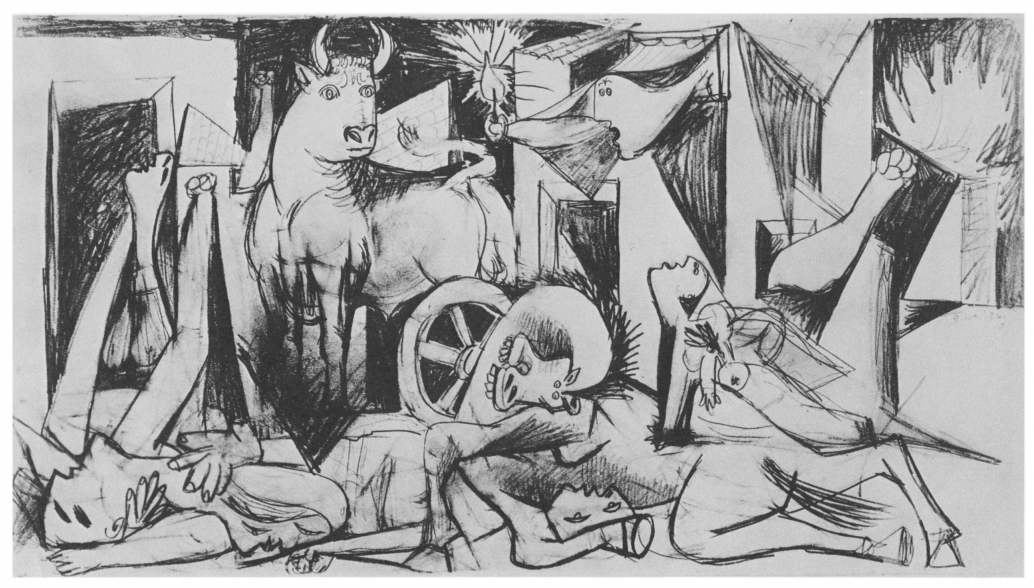

On 1 May, Picasso begins with four sketches for the composition and two studies for the horse. On 2 May: only three sketches. For five days: nothing. He knows what he is going to make and does not yet want to fix his ideas: "In the beginning one should have an idea, but a vague one," he confides to Kahnweiler. He wants to remain free as long as possible.

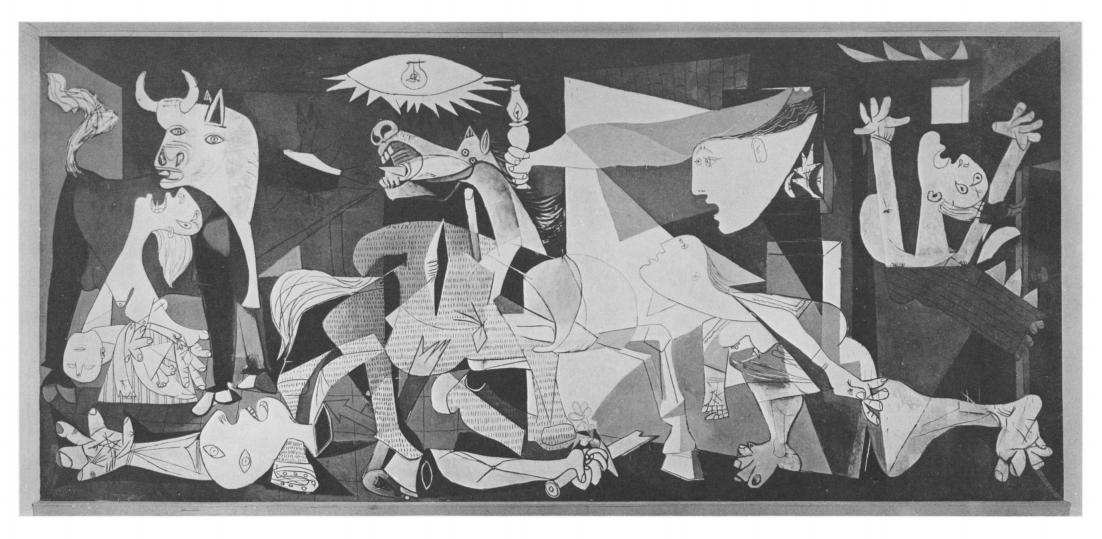

Evidently during these days the big canvas, 11 feet 6 inches by 25 feet 8 inches, is being prepared. Then, from 8 May, the work goes on without interruption: compositional sketches, and studies for the bull, the horse, and the weeping woman.

On 11 May the canvas is ready, and immediately the composition is laid down as a linear structure that covers the whole surface. Work on the mural is accompanied by more than thirty studies for the details. The rough plan exists from the beginning, but it takes three weeks before the picture receives its final form.

The bull’s head remains where it was first put, but the body is turned around to the left. On 20 May the horse lifts its head. The body of the soldier stretched on the floor from left to right changes position on 4 June, then head and hand take on their finished shape.

At the last moment the artist makes one decisive adjustment: the drama first took place on a street with burning houses in the background. Now, suddenly, the diagonals are accentuated, and thereby space becomes ambiguous, unreal, inside and outside at the same time. The lamp is hung over the horse's head, looking on the dreadful scene like a wide-open eye. The construction is strengthened, the mural more strongly integrated in Sert’s architecture. Into the hand of the dying soldier, next to the broken sword, Picasso puts the little flower of hope.

The picture was finished about mid-June. Hundreds of thousands of exhibition-goers wandered by, looking on it as a wall decoration, just as Europe wandered by the human drama of the Spanish Civil War—as if it were a matter concerning only the inhabitants of the peninsula. They disregarded the warning, did not understand that democracy on the whole continent was at stake.

Only a few in 1937 understood Picasso's dramatic appeal as we might understand it now.

Today “Guernica” has become a part of the pattern of our own experiences. It is the pathetic symbol of the recent past and a warning for the future.

When seen in the light of “Guernica,” all Picasso's earlier works look like preliminary stages, studies for the creation of a new language. This new language stands at the artist's disposal when, stirred by the weight of human fate, he is driven to take part with his own weapons in the great battle for freedom. Thus “Guernica” is an expressionistic message, written in the language of Cubism.

Picasso’s great achievements are on two totally different levels: through the creation of Cubism (1907) he gives us a new vision of reality; by painting “Guernica” he transforms a stark act of war into an eloquent warning to humanity (1937).