Recognition, Repair & the Reconstruction of “Square One”

The concept of a “square one” in societal organization is a curious thing, and challenging analytic, given the stubborn presence of the past. Even if not meant literally, the Square One Project, like much of the polity, envisions a new starting point, where social policy and practice might turn in a more equitable and inclusive direction. Yet we must grapple with what this restarting point is, in a sociological rather than political sense, and how the present can reasonably be conceived–and actively reconfigured–as an opportunity to start over. I argue that the Square One Project imagines yet another societal reconstruction, in which attending to old and more recent histories of racial violence remains critical to achieving a sustainable vision and practice of equal and legitimate justice. To that end, I encourage a wide-ranging array of efforts under the banner of monumental antiracism to prepare the ground for square one justice.

History is not the past. It is the present.

—James Baldwin

The concept of a “square one” in societal organization is a curious thing, and challenging analytic, particularly from the vantage of our embodiment of the past. This is an important problem to consider within the organizing query of the Square One Project: “if we start over from ‘square one,’ how would justice policy be different?”1 Even if the phrase is not meant literally, the project, like much of the polity, envisions a new starting point, where social policy and practice might turn in a more equitable and inclusive direction. Yet we must grapple with what this restarting point is, in a sociological rather than political sense, and how the present moment can reasonably be conceived as an opportunity to start over.

There is a palimpsest problem with the idea of square one; our restarting point is an overlay on what has come before, with visible traces of that past remaining ever present. How do we reimagine and transform justice while other ideas and practices of justice continue to shape the organization of the society in ways that reproduce centuries of inequality? We surely cannot literally recreate or return to societal square one, since we cannot undo this past and its presence, including such definitive American histories of settler colonialism, genocide, enslavement, apartheid, and mass incarceration. We also cannot easily escape their haunting shadows in contemporary social relations. Therefore, we must face their legacies today, as problems at square one, turning this record of atrocity into a kind of light, and resource in repair.2

The Square One Project is a lively site of democratic deliberation over the future of justice. There is likely nothing comparable in scope and scale in the world today, as this specific and critical question–the future of justice–is concerned. It is therefore an important opportunity to achieve a more transformative transitional justice process, in our postconflict society that is not past conflict.3 Freeing our political culture from the trappings of this past, including racialized penchants for punitive excess and unequal protection under law, is among the greatest challenges for square one justice.4

We are at a historically familiar crossroad, a familiar moment of national reflection on the past, present, and future of social (in)justice. We have been here before, of course, and failed to make the turn toward an open society substantively organized by mutual respect, equality of opportunity, and protection in law. Though such opportunities have typically been lost, often sabotaged or otherwise squandered, they remain vital to articulating, building, and maintaining the society we want for ourselves and others.

The Square One Project imagines (another) societal reconstruction, in which attending to legacies of historical racial violence remains critical to achieving a sustainable vision and practice of equal justice. As Danielle Sered, founder of Common Justice, writes in Until We Reckon, “[we’ll] be tempted to look only forward because what is behind us is so hard to face,” but failure to confront this difficult past will deprive us of transformative change, as it has so often before.5

These challenges are not new, nor is the sense that an opportunity for transformative justice might again be near. Contradictions of American democratic proclamations, including the unjust rule of law and flaunting of vaunted freedoms, have long been clear to see and have always been contested. This historical pattern includes a relatively constant longing for transformative social change, a cyclical sense that this new day draws near and, finally, lament over opportunity lost, resetting the routine. Even before White settler colonialism took firm root as the orienting principle of these lands, rationalizing genocide, enslavement, and an explicitly White democracy, the people faced a similar choice of whether to institutionalize freedom and equality, or exploitation and exclusion. W. E. B. Du Bois wrote of this early period of American history that “the opportunity for real and new democracy in America was broad,” as investments in liberty were substantial, and the choice of White racial tyranny was not a foregone conclusion.6 That opportunity was lost, and has been ever since, at subsequent crossroads, where there was something like a mirage of square one.

The nation reached a similar fork in the mid-to-late 1800s, when brief interludes of emancipation and Reconstruction would turn out merely to bridge eras of chattel slavery and reconstituted apartheid. Then, too, questions of ambition and organization of social change were paramount. Radical abolitionists warned in the 1840s that the nation could not easily transition from a society built on enslavement to a dignified civilization committed to freedom. The U.S. Constitution that Garrisonians plainly characterized as “a covenant with death” would have to be reconstructed, having been explicitly designed as a bulwark of racial slavery, rationalizing and institutionalizing America’s democratic contradictions. Instead, of course, the Constitution was merely amended and, as Ava DuVernay’s film 13th dramatically portrays, continued to facilitate racist exploitation and exclusion, including Black Codes, convict leasing, and more contemporary regimes of racialized social control.

At each turn, the nation has proved unwilling to reconstruct law and society transformatively. Rather than prioritize or fashion that “square one,” where a genuinely open society might grow anew, the nation has opted instead for more reformist transitions, limited in commitments to equal opportunity and protection, with predictable results. Several of my Black ancestors lived in Wilmington, North Carolina, in the 1880s, a place that was for a fleeting moment regarded as the most progressive city in the post-emancipation South, owing to its integrated neighborhoods and relative economic and political equality. These ancestors owned their own businesses and considerable property in Wilmington. They held public offices, serving in the state legislature and municipal government, including fire and police services, and were leaders in city schools. That experiment in racial democracy ended violently in 1898 when Black political and economic competition inflamed White rage, leading to a racial massacre and coup whose legacies linger today. Uncommitted as they were to radical Reconstruction, state and federal government turned a blind eye to the atrocities, enabling coup conspirators to remove the democratically elected government, installing their leader as mayor and many of the paramilitaries who had carried out the massacre as a new city police force.7 Their racial terror would continue, now under the color of law, contributing to legal estrangement and cynicism that still endure.8 What was for a brief slice in time the most progressive Southern city was thus rebranded the capital of White supremacy, inspiring a reign of racial terror and Jim Crow over the ensuing half-century and more.

We blew past another fork in the road during and after World War II, when the fight against fascism abroad cast a critical light on American racial tyranny. The “Double V” campaign of Black soldiers–fighting for victory abroad and demanding it at home–envisioned a democratic transition that was not to come, including in policing and other realms of the American legal system. One of the demands then, as now, was representative systems of social control, which required a dismantling of the White supremacist legal system built on the ashes of Reconstruction. “To extinguish the memories of black jurors, judges, police and legislators during Reconstruction was to make clear the undisputed and permanent authority of whites,” writes historian Leon Litwack.9 In the subsequent build-out of American apartheid, “The entire machinery of justice–the lawyers, the judges, the juries, the legal profession, the police–was assigned a pivotal role in enforcing these imperatives . . . underscoring in every possible way the subordination of black men and women of all classes and ages.”10 Many city police forces only began to reintroduce non-White officers in the aftermath of World War II, yet these officers were incorporated in ways that reflected and reinforced the entrenched White supremacist political system, or the imprint of the past.11 Black soldiers were particular targets of White supremacist violence, given the distinct threat and outrage of their status, coupled with their emboldened challenges to American apartheid.12 That history still rings, ironically and traumatically, amid contemporary complaints that antiracist protests–such as kneeling during the national anthem–disrespect “our troops.”

Freedom movements of the mid-twentieth century carved another fork in the road of American history, again drawing scrutiny to racist police violence and otherwise undemocratic policing. There were familiar calls to end police occupation of poor communities, dismantle the police state, extend and enforce constitutional rights to due process and equal protection, and otherwise increase the democratic accountability of government. Despite important legal gains, these were soon overshadowed by racialized wars on crime and drugs, with poor youth of color defined as enemies within. As a high school student in Los Angeles in the late 1980s, I grew used to the harassment and threats of police authorities, who routinely used a pretext of “gang investigation” to train their guns on us, to physically and verbally abuse us, and to deprive us of constitutional rights that no one seemed to take seriously, notwithstanding all of the progress promised over the preceding century, at all those earlier crossroads.

If the past is prelude, prospects for truly transformative change still look dim today. Yet we are in a unique historical moment in terms of strategies and resources. Technological and societal changes have created new forms of political capital, such as camera footage challenging White norms of willful ignorance, coordinated protest actions spanning virtual and physical spaces, and grievance areas fueling movement alliances and pressures that did not exist in earlier moments (for example, resisting “toxic prisons”). There are also new ideas, including growing and compelling calls for a society without police or prisons, born of recognition that police often violently escalate situations, especially in encounters with non-White and otherwise marginalized populations, and that there are better options for social problem-solving than policing or imprisonment. This latest wave of critical analysis and political mobilization has clearly pushed us to this point of reckoning, another fork in the road of our national story, where the plot just might turn toward a realization of racial justice, or so we want to believe.

There is another important reason to be encouraged about the potential to build a movement advancing transformative justice. That is, we know more about this palimpsest problem, including how it might be countered, than we ever have before. This work informs my emphasis on specific challenges of recognition, and discussion of repair.

Square one is haunted ground. That is, the living history of racial violence, or the problem of the presence of the past, is perhaps the greatest challenge to the concept of square one. Racist violence has been perpetrated regularly under the color of law, typically with civil and criminal impunity for its perpetrators, the aiding and abetting of legislators and executives, and the willful ignorance and indifference, explicit endorsement, and active involvement of the polity. Besides the spectacular violence of police and vigilante killings, there is the subtler state violence of criminalization and incarceration, and dispossession and dislocation, including deportation, which has played out over centuries, exacting immeasurable economic, political, and cultural tolls on generations of Americans. Even if this were all to end today, this toll would remain unresolved, the haunting shadow of historical racial violence.

Long histories of racialized violence affecting Native American, Black, Latino, Asian, and Pacific Islander populations are not merely losses of well-being, opportunity, or standing for immediately impacted populations, but are conveyed intergenerationally as inheritances of historical trauma and dispossession. Further, these harms have correspondingly advantaged generations of White Americans, materially and otherwise, in what amounts to a continuous transaction, often through extraction, congealing in the structural and cultural sinew of “durable inequality.”13 This matrix of social opportunity and closure, of White opportunity hoarding and accumulation reliant on disinvestment and decumulation, is not bound by the present borders of the United States. Rather, these relations of extraction must ultimately be viewed from a transnational perspective, in the relationship between the Global South and North, for instance, and in relation to the formation of the U.S. nation-state itself, within a much larger racist world system. If not always plain to see, mechanisms and legacies of these relations of racial dominance continue to circulate the globe, and it is questionable whether the United States can transform justice policy and practice without corresponding changes in this interconnected world system.

Setting that global question aside, and recalling Frederick Douglass’s 1852 speech reflecting critically on the meaning of American Independence Day to the enslaved, we might productively ask, “what to the Black or brown American is square one?”14 The answer is clearly complicated by centuries of racialized violence–direct, cultural, and structural–that remain bound up with group identities, experiences, and prospects today. As African American literature scholar Saidiya Hartman reflects on the legacies of enslavement,

Slavery established a measure of man and a ranking of life and worth that has yet to be undone. If slavery persists as an issue in the political life of black America, it is not because of an antiquarian obsession with bygone days or the burden of a too-long memory, but because black lives are still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery–skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment.15

This entrenched racial calculus and its peril do not originate in the era of enslavement. This legacy draws on other atrocities throughout the history of this settler society, and links to others around the world, in its dynamic imprint on the present and future.

There is a broad and deep body of scholarly work charting these intergenerational impacts of historical racial violence. In City of Inmates, for example, historian Kelly Lytle Hernández traces historical linkages between the White racial project of conquest, rationalized as “manifest destiny,” and a series of “eliminatory” measures on lands reconstructed as California, including ethnic cleansing, settlement through displacement, and mass imprisonment.16 Historian Monica Martinez traces similar histories and legacies in The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas, showing how atrocities of the Texas Rangers (such as massacres and dispossession), and subsequent denials of recognition and recourse by politicians, courts, historians, and journalists, sustain the traumatic stress of this state violence for descendants today.17 Similar research examining historical trauma in American Indian and Black community contexts, such as genocide and forced relocation, suggests its legacies are literally embodied by descendants, contributing to health disparities, loss of collective efficacy, and other adverse outcomes.18

Social ecological dimensions of embodied trauma, and implications for redress, are also clarified in a series of empirical studies relating histories of genocide, enslavement, lynching, and other race-based violence and repression with heightened conflict, violence, and inequality in the same places today.19 These statistical studies find that racial animus and political conservatism are consistently heightened among Whites living in U.S. counties with more pronounced histories of enslavement, in comparison with Whites in neighboring counties, historically and today; they have shown that contemporary support for punitive crime policy, including capital punishment, is greater among White Americans in counties marked by histories of lynching.20 Area histories of enslavement and lynching correspond with many other contemporary patterns of conflict, violence, and inequality as well, including Black victim homicide rates, hate crime law enforcement, White supremacist mobilization, heart disease mortality, infant death rates, and the use of corporal punishment in public schools.21

There is an urgent need for greater recognition of these legacies and reparative interventions that might break these cycles of repetition. These are problems of reconstruction for square one, where more direct challenges of these embodiments of past injustice–confronting their cultural and structural dimensions–are key to redefining ideas and practices of justice.

What Hartman has called the “racist ranking of human worth” continues to trivialize Black and other lives relative to those of Whites.22 The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and White reactionary opposition to it are illustrative here. Opposition to the trivialization of Black lives (as by Black Lives Matter) has been met with considerable resentment, including the durable challenge countering that blue (police) lives matter more. This weighting of racially defined lives, including equations between police and anti-Blackness, and Whiteness itself, is a critical challenge for the square one agenda. To turn away from a history of justice policy and practice in the service of White racial dominance, and associated anxieties and entitlements of White supremacism (explicit or implicit), interventions cannot focus on the circumstances and interests of the non-White population alone; we must reckon with the square one problem of Whiteness in U.S. and global political culture and behavior.

We might broadly conceive of one of square one’s “grand challenges” as abolishing the “racial contract,” that racially violent “rider” on the social contract defining Whites alone as full persons, entitled to its provisions of trust and cooperation.23 We cannot reasonably envision a new direction in justice policy without an end to this privileging of White bodies and their putative interests. Reconstructing square one requires disabusing White Americans of the incredibly deep-seated if often unconscious sense of their being “masters of national space,” constantly threatened, and deserving of their social dominance.24 This identity and associated roleplay, rooted in noted histories of White settler colonialism, and manifest in slave patrols, White citizens councils, and all-White police forces, juries, and court and legislative bodies, to name a few forms, has recently been animated by the likes of “Barbeque Becky” and “Permit Patty,” whose individualized and playful memes distort the historically persistent threat of collective racist actions.25 This is perhaps the heart of the White supremacist social body, the lifeblood of its collective violence, contributing to premature deaths of the masses at the hands of Whiteness, historically and today.

It will be incredibly challenging to center the violence of Whiteness in reimagining justice policy, given routine denials that it exists. This is precisely why truth-telling and bearing witness, through remedies of recognition, are essential to what I characterize as the reconstruction of square one. Political philosopher Charles Mills argues that moral and political dimensions of the racial contract, wherein non-Whites are diminished relative to Whites in terms of their moral and political standing, are facilitated by an epistemological dimension, involving “agreement to misinterpret the world.” He explains,

White misunderstanding, misrepresentation, evasion and self-deception on matters related to race are among the most pervasive mental phenomena of the past few hundred years, a cognitive and moral economy psychically required for conquest, colonization, and enslavement.26

This problem of “motivated ignorance” has to be anticipated and overcome in reckoning with the violence of Whiteness central to square one, given its historically long-standing role in obstructing movements for freedom and equality, and rationalizing racism.27

Vitriolic retorts to the antiracist recalibration claim that “Black lives matter” are again instructive. Rejoinders to BLM protests, including that blue lives matter (more, or instead, it would seem), belie an oppositional and relational orientation to the valuation of Black life. The demand of equal regard for Black life registers as a threat to, or unjust imposition upon, racially defined others (including putatively White police), within our political culture. This zero-sum orientation toward White standing (where White freedom is equated with dominance) is clearly evident, historically and today, and is a primary driver of the cultural, structural, and direct violence of racism.28

Juxtapositions of Black and police lives are particularly important in the context of the Square One Project, and relevant to my argument here, since they draw to the case of policing the noted abolitionist warnings that the Constitution cannot be revised to ensure freedom and equality but must be reimagined and reconstructed instead. Is American policing a “covenant” with Black death? Or, if it has been so historically, why should the public believe that it is not still today? Can American policing be reformed if explicitly and implicitly understood to exist for the service and protection of White society? If policing has long been integrated with White nationalism in the United States, and continues to be today (for example, blue lives are not Black), what is square one in police policy or “police-community relations”?

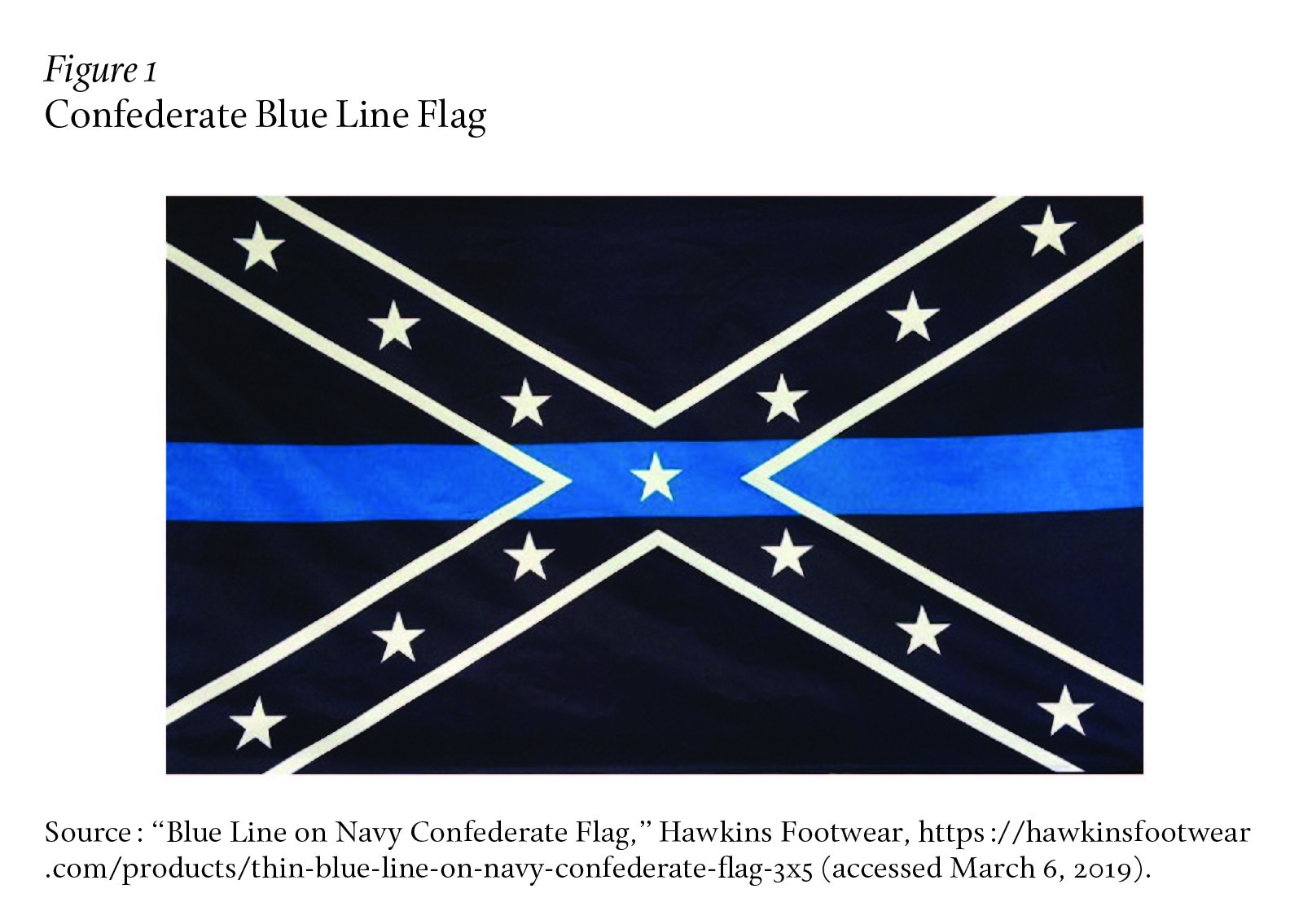

An extreme but telling example of this enduring association is the cultural production and consumption–and thus the political imprint–of an image that bends time and place to convey the legitimacy of racist police violence. This design sorcery, a “thin blue line” rendering of the battle flag of the Confederate States of America (Figure 1), both embodies and actively sustains the contested (and threatened) cultural-political logic of White supremacist policing.29 One store pitches the flag as a great way to “back the blue,” encouraging its (presumably White) customers to “support Southern police,” adding that this bestseller “makes a perfect gift for your favorite [presumably White] peace officer.”30 The flag design, a twenty-first-century emblem of the lasting compromise of freedom, explicitly trades in the White supremacist politics of the culturally integrated rather than the expelled Confederacy, wielding these in opposition to an existential threat in the Movement for Black Lives. Indeed, consumers on another site appreciated utilities of the flag itself for enduring fantasies of conquest. A reviewer going by “KKK supporter” commented that the flag is “great choking supply for BLM scum.” A reviewer named “Racist Guy” writes, sarcastically perhaps, “I mean, how are people going to know that I support white supremacy and police brutality against minorities without a flag? Oh yeah, my Trump bumper sticker does it. But a flag is nice.”31 Sales of the flag are reportedly brisk, and historical connections between confederate symbols and racist violence are significant. It is noteworthy that the largely online vendor of the flag discussed here has operated out of a location in Brunswick, Georgia, just ten miles from the neighborhood where three White vigilantes–including a former police officer–were convicted of murdering Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery in 2020.32 Those suspects were only arrested and charged after months of protest.33

There are myriad examples of the relationship between White supremacism and policing, historically and today. Generally, these involve police themselves engaged in White supremacist violence or withholding protection from White supremacist threats.34 These relationships are not limited to police officers, of course, but may involve any formal and informal operative of social control. A formerly incarcerated student recently shared that he was incarcerated in a Midwestern state prison when President Obama was elected to office. He explained that although he had not been able to vote, he and other Black prisoners responded with joy to the news of the outcome of the national election. That celebration was construed by generally White conservative prison guards as “causing a disturbance,” who further abused their incredible discretion by placing Obama celebrants in solitary confinement. As recent revelations of police corruption rooted in alliances with White nationalists illustrate, White supremacism continues to course through the veins of U.S. legal and law enforcement institutions, limiting the prospects of starting over from square one or, perhaps, keeping us where we began.35

The square one problem of Whiteness is not only the long history of associated racist violence and its legacy today, but that antiracist policy will be framed and countered as “anti-White” measures, rational interests be damned. Many White Americans remain unwilling to relinquish a social status and perceived advantages rooted in non-White subordination and disadvantage, even as this sustained “covenant with death”–manifesting as educational divestment, limited health care access, increased gun ownership and lethal gun violence, war mongering, and so on–yields a growing toll of Americans and others around the world who are “dying of whiteness.”36

Problems of justice can be too narrowly framed in relation to policing, courts, and prisons, as it is clear that these systems interface with numerous other sites of punitive excess (such as labor markets, schools, and the environment), and that these relationships are themselves key in bridging histories of racial injustice with legacies today. This web struck me while participating in a dialogue in Birmingham, Alabama, where police and community leaders gathered to discuss how that city might address its long and traumatic history of racist police violence, and the role of police in denials of human and civil rights. The aim of the conversation was police-community “reconciliation,” a term related to the noted mirage of square one, alluding to a prior conciliatory relation that has never really existed.37

Yet it remains the case that many people in this community and many others are deeply invested in more legitimate and democratic policing, most of all for its apparent promise to improve the quality of life (including public safety), increase trust and cooperation, and enhance group (including youth) prospects, by countering attitudes and practices of racialized criminalization and control. This determination to institutionalize and routinely experience dignity, equality of opportunity, and protection under law raises a vast complex of cultural and institutional forces, involving many areas of law and policy, various branches of government and realms of the private sector, and nearly infinite endogenous determinations of legal meaning in everyday life. Transforming municipal policing would be a start, but even this impact would be limited by the narrow way we tend to conceive of the justice workforce, law enforcement roles, or “public safety” personnel, excluding such decisive actors as teachers, curators, librarians, public health professionals, and custodians of the environment, all of whom manage exposures to “punitive excess.”

At the Birmingham meeting, I grew fixated on the reality that improving police-community relations, or emptying prisons, or revising criminal codes would be unlikely to stop this cascade of punitive excess. I have already stressed the more complex and compounding array of injustice this better future would have to negate, not only in the sense of a cessation, but in terms of the already embodied trauma we must also somehow resolve. There are other challenges as well, such as the punishing toll of environmental racism, a problem of public safety reflecting profound injustices of underprotection in law, policy, and practice, contributing to disproportionately Black and brown deaths of neglect and despair.

Square one is not only figuratively contaminated by past use, but often literally a “brownfield,” with complex justice implications.38 Before heading to Alabama, I scanned the recent news, hoping to get some bearings on the kinds of issues local residents and police might be working through. I was struck by this headline, “On a Hot Day, It’s Horrific: Alabama Kicks Up a Stink Over Shipments of New York Poo.” Indeed, human waste from New York and New Jersey, no longer permitted to be dumped into the rivers and sea, was being shipped to hazardous waste sites in Alabama. The state has become a leading recipient of various types of toxic waste.39 One of the largest of these sites is in the Black settlement of Uniontown, Alabama, where the population is nearly 90 percent Black, where the median income is less than $14,000 per year, and where garbage from thirty-three states is dumped, along with four million tons of coal ash generated from a coal mine in a 90 percent White community in Tennessee.40

The Uniontown landfill occupies a former plantation, around which generations of enslaved people were buried in unmarked graves, and now under this hazardous waste. “If this had been a rich, white neighborhood, the landfill would never have gotten here,” one Black resident protested, noting that a county commission had continuously granted permits to the site over the objections of Black Uniontown residents. This complainant, whose sharecropper and enslaved ancestors toiled on local plantations, reasoned the punishing waste was located there because state and county officials who are tasked with policing these sorts of threats to public safety “knew we couldn’t fight back.”41 This is but one of the many disproportionately poor and non-White populations residing amidst stews of “toxic oppression and oppressive toxins” across the United States, including scores of prisoners and workers toiling in toxic prisons, penal institutions sited in areas of environmental contamination.42

Communities are fighting back by opposing additional exposure and challenging that decisions to expose them selectively to hazardous waste violate civil rights law. Meanwhile, residents in Uniontown and similar places experience adverse health effects and incur associated costs of this environment of racism (such as in cognitive development, chronic illness, and present and future education and employment outcomes), many of which correlate with criminal justice system contact. The ordeal signals the vast scale of the square one problem, in which a complex circulatory system of historical and contemporary injustice–histories of enslavement and other exploitation, of lynching and other racial terror, of hyper segregation, surveillance, criminalization, and control–course through human and social bodies, keeping the “covenant with death.” If justice policy and practice are indeed to take root in a new square one, this historical system of recirculated racial violence, sustaining cycles of racial violence, conflict, and inequality, poses an incredible challenge of reconstruction.

In a recent interaction at a bar on the Upper East Side of New York, after I had explained that my scholarly work engages the problem of racial (in)justice, a retired White executive sitting by my side turned to me and asked, earnestly, “is there really bias in the criminal justice system?” This is the fairly common performance of motivated ignorance I referenced above, which often involves outright erasure of the history and presence of White racism or diminution of its societal toll. During the 2016 presidential election, the Democratic candidate surprised me with her claim that we must “restore trust between police and Black communities,” as if it were once widespread. This is a common refrain, at once reflective and regenerative of a political culture of nonresponse, or compromise, through diagnoses and treatments that are not transformative.

President Obama perpetuated the illusion when he declared late in his presidency that “our systems for maintaining the peace and our criminal justice systems generally work, except for this huge swath of the population that is incarcerated at rates that are unprecedented in world history.”43 This incredible and telling exception to a claim that “all is well, otherwise” not only downplays the punitive excess of mass incarceration but interrelated problems of impunity for economic and political elites in our criminal and civil justice systems. Of course, our systems of justice have never worked for everyone, so they have never worked for anyone, in an ethical and sociological sense. These failures are catastrophic, relating directly to the atrocities I have emphasized here.

Unless we create a political culture actively disavowing the histories and legacies of White supremacism and associated injustice, these compromises are likely to continue. As with emancipation, Reconstruction, and civil rights reforms, we will keep patching up the most atrocious evidence of our enduring “covenant with death,” rather than build a just society. One wonders if we can fully imagine a just society without first or simultaneously disembodying the trauma of White supremacist violence: cultural, symbolic, and direct. The epistemological dimensions of White supremacism and racial hierarchy–the routinized delusions and falsehoods–prevent the transformation we can only achieve through truth-telling, and by building new norms and institutions on the foundations of those truths.44

This challenge seems to require monumental antiracist contestation, in a figurate and literal sense, reshaping the landscape of remembrance in ways that actively contribute to repair. This is not merely or primarily a problem for law and policy, but rather it calls on a number of fields to engage in uncompromising contestation of the legacies of racist violence through acts of recognition and reparation. That reconstruction of square one would draw on disparate fields such as education, art and design, and computer science, and their platforms for this monumental effort, both in the sense of “massive resistance” and in the sense of building the durable cultural and institutional infrastructure needed to sustain new norms of equal justice. The potential interventions include early childhood through advanced education, in which new approaches to truth-telling and bearing witness can have lasting impacts on political culture and behavior, breaking the current of racial violence we have so far carried across generations.45

Other interventions could leverage art and design to engage in various types of “visual redress,” both by contesting art and design elements of racialized social control, and by advancing art and design aspects of transformative racial justice.46 The recent exhibit of painter Kehinde Whiley, St. Louis Portraits, is a useful example here. The collection uses massive and compassionately detailed paintings of Black St. Louisans to simultaneously bear witness to White supremacist ideologies embodied in art and employ art as a reparative resource, using the fine art portrait style to valorize this “despised collectivity,” leveraging the ritual of art consumption in museums to literally mount antiracism.

In its plan to release “spores of memorium” across the U.S. landscape, physically building collective remembrance of racial terror and lynchings into the land, the Equal Justice Initiative also practices what I have characterized as monumental antiracism. These markers, as durable sites of recognition, promise to facilitate other acts of repair. As such, the active contestation of racial violence on the commemorative landscape, pressing for removal and recontextualization of White supremacist cultural markers and mounting of antiracist commemorative measures, is another illustration of education, art, and design being used to reconstruct square one.

To be sure, our reconstruction cannot be achieved through commemorative interventions alone. The revolution will not be a children’s book, college course, provocative painting, historical marker, or other work of curation, but all of these are still relevant to the transformation of political culture needed to reimagine and reorganize justice. The nature and extent of their impact is an empirical question warranting closer consideration, and yet it is clear that these are relevant sites of repair, where we might be weaned from the “covenant with death” and truly prepare to embody the principle of equal justice.

“We must reimagine a new country,” writer Ta-Nehisi Coates instructs in “The Case for Reparations,” echoing the Garrisonians and many others since.47 Imagination is not enough, yet it is clearly indispensable to the task of preparing our sick and disfigured social body to appreciate and receive the kind of life-supporting transplant imagined by square one justice. Without that preparation, the political culture is likely to reject that intervention, as it has at all earlier crossroads. “Reparations–the full acceptance of our collective biography and its consequences,” Coates writes, “is the price we must pay to see ourselves squarely.”48 That foundation of repair offers the closest possible approximation of square one, replacing the mirage with a more literal restarting point and realistic basis for a just future.