Social Justice Challenges of “Teaching” Languages

This essay explores the challenges to linguistic justice resulting from widely held negative perspectives on the English of young Latinx bi/multilinguals and from common misunderstandings of individuals who use resources from two communicative systems in their everyday lives. I highlight the effects of these misunderstandings on Long-Term English Learners as they engage with the formal teaching of English. I specifically problematize language instruction as it takes place in classrooms and the impact of the curricularization of language as it is experienced by minoritized students who “study” language qua language in instructed settings.

Long-Term English Learner (LTEL) is a legal category for students in the State of California. It is used to describe immigrant-origin students who were initially categorized as English Language Learners (ELLs) upon entering school and whose test scores, after six years, suggest that they are not making sufficient progress in learning English. The legal LTEL category is the product of a well-meaning political campaign launched by sympathetic supporters of Mexican-origin students in California (for example, Californians Together) who claim that more attention needed to be given to the teaching of English in schools and to reclassifying ELLs as Fluent English Proficient (FEP).1 Advocates of the legislation argued that, because of lack of attention by schools to the teaching of English, many Latinx ELLs in California were not passing the state English Language Proficiency examination required to reclassify them. As a result, they were denied access to challenging subject matter instruction, to college-preparation courses, and to other important educational opportunities. The new legislation requiring schools to identify and monitor students was envisioned as a way of bringing attention to the unintended consequences of existing policies and of forcing schools to implement quality English language development programs designed to meet the needs of young ELLs.

A Google search for “LTEL” yields 594,000 results to education-related sites that include school district policy documents relating to the challenges of educating such students, guides for administrators and educators, ads for curricular aids and materials, and lists of characteristics of LTEL students. A Google Scholar search produces over seven hundred fifty articles, some of which prescribe approaches for remediating the assumed language limitations of LTEL-designated students and others that question the validity and usefulness of the category itself.

The LTEL label has created a category widely used around the country that positions students “new to English” as out of step, as failing to move at the “right” pace in their additional-language acquisition trajectories. In using the term and establishing the category of LTEL, the educational community is formally making the case that a specific group of students is not making academic progress. The category, moreover, is based on widely shared expectations underlying established educational policies that make the assumption that students initially labeled ELLs can be 1) accurately identified in early childhood and 2) supported with adequate educational “services” leading to successful performance on state mandated English language proficiency examinations. Unfortunately for Latinx students, the path to reclassification as FEP is much more challenging than originally expected. Policies and procedures established to “teach” English, to support subject matter learning, and to assess students’ levels of English proficiency leading to their timely reclassification have, over time, led to unforeseen consequences. Sadly, as determined by varying state and district classification criteria in different parts of the United States, many students who have been bureaucratically categorized as ELLs since kindergarten are now currently identified by state assessment systems as “failing to acquire English.”

For Latinx youngsters, the extensive use of the LTEL label along with frequent criticisms of their spoken Spanish on social media suggest that these young people are being seen (and perhaps are also seeing themselves) as languageless.2 Taken together, both labels imply that these young individuals speak neither English nor Spanish well or possibly at all. In the case of LTELs, the description of languagelessness is clearly impacting Latinx students’ educational lives and futures more directly. In the ongoing analysis and prescription of remedies for perceived linguistic limitations, formal language study is invariably identified as the principal solution. LTELs need more ESL (English as a second language) classes.

In this essay, I explore the challenges to linguistic justice resulting from widely held negative perspectives on bi/multilingualism and from common and continuing misunderstandings of individuals who use resources from two communicative systems in their everyday lives. My goal is to highlight the effect of these misunderstandings on the direct teaching of English. I specifically problematize language instruction as it takes place in classroom settings and the impact of what I term the curricularization of language as it is experienced by Latinx students who “study” language qua language in instructed situations. I analyze the activity of language teaching itself and argue that, while existing work in critical applied linguistics (for example, Alastair Pennycook’s study on the teaching of English as an additional language across the world) is an important first step, it has not yet penetrated the various levels of the powerful language industry teaching English to immigrant-origin students.3

In the American educational system, Latinx children and particularly Mexican-origin children are considered “disadvantaged.” They are part of a class of students whose family, social, or economic circumstances have been found to impact negatively on their ability to learn at school. These young people are both minoritized and racialized, and their educational experiences are impacted strongly by well-meaning educational policies—focusing on language—that directly contribute to both exclusion and inequality.

The category of English Language Learner was established in federal policy as part of the Civil Rights initiatives of the 1960s, the passage of Title VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) in 1967, and the Lau v. Nichols Supreme Court decision of 1974.4 Following the Lau decision (which established that students could not be educated in a language that they did not understand), the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 required states to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers and provide equal opportunities for children. This legislation led to extensive debates and court challenges during the 1970s and 1980s that focused on the types of remedies (for example, ESL pullout programs and bilingual education programs) that would be required in order to provide opportunities for children who were in the process of acquiring English. Over time, there has been strong opposition to bilingual education, numerous lawsuits seeking to compel school districts to serve the needs of Latinx students, and shifting federal and state regulations and guidelines.

In 2001, the shift to standards-based educational reform in the country (deregulation at the federal level in exchange for demonstrated educational outcomes) led to the No Child Left Behind Act, to strong accountability provisions, to the establishment of detailed English Language Learner classifications, and to increasing opposition to bilingual education.5 In 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) reauthorized the fifty-year-old ESEA, the national education law seen as a long-standing commitment to equal opportunity for all students. ESSA established reporting requirements for all states and Local Education Agencies (LEAs) on ELLs’ progress in attainment of English language proficiency, on academic achievement, and on high school graduation rates.

Currently, the use of any non-English language at home has direct consequences for all children who enter the American educational system. Upon enrolling children in school, parents are required to complete a home-language survey and specifically to identify the language spoken at home. The assumption is that children raised in homes where a non-English language is spoken may themselves be non-English-speaking or ELLs. In theory, screening for home language allows schools to appropriately serve the needs of all children entering schools by classifying them as English Only (EO), Initially English Proficient (IEP), or ELLs. In the case of Latinx families, even when children may already speak and understand English, reporting the use of Spanish in the home almost always results in their being categorized as ELLs, an identification that directly affects their educational trajectories and opportunities to learn. Importantly, schools receive additional funds for ELL-classified students.

English is currently taught as an additional language to students who are categorized as English Language Learners. By law, all students so categorized must be provided with “language assistance” and assessed every year until they are reclassified as Fluent English Proficient. Language assistance, however, has been variously defined. Over the last fifty years, different states have recognized a variety of approaches for delivery of this assistance to children ranging from 1) providing subject matter instruction in students’ home language and gradually transitioning to instruction in English; 2) requiring periods of designated English language development (that is, direct teaching of ESL using pedagogies adapted from the teaching of ESL to adults); and 3) implementing instruction described as integrating both English and subject-matter content.

Each of these approaches involves the direct teaching of an additional language to young children. In the case of the first approach (known as bilingual education), English is used gradually as a medium of instruction complementing the use of children’s home language to teach academic content. In many programs, however, explicit teaching of English vocabulary and/or forms is also included.

The second approach, referred to as Structured English Immersion (SEI), involves the adaptation of explicit language-teaching methodologies used traditionally for the teaching of English as an international language to adults. Such instruction often takes place in pullout ESL programs that group children by language levels (beginning, intermediate, advanced) for segments held separately from monolingual English coursework. Known as “leveled” English Language Development (ELD), this approach limits ELLs’ access to fluent English speakers and opportunities for imitating or interacting with such speakers.

The third approach directs the teacher to structure subject matter teaching (for example, math, science, initial reading) to include mini lessons on grammatical structures and forms, such as phrasal verbs. Popular in many parts of the country, this approach, often marketed to school districts as SIOP (Sheltered Instructional Observation Protocol), requires that teachers develop both content and language teaching objectives for each lesson. Unfortunately, even if teaching structures and forms to children were effective—a point numerous experts have questioned (for example, Michael Long and H. D. Adamson)—very few elementary or secondary content teachers have the background to do so without sacrificing either the teaching of English or the teaching of subject matter content.6

In many districts, there are specialized newcomer programs—particularly at the secondary level—in which students new to the country and to English are provided intensive, traditional language instruction for a period of time in lieu of enrollment in regular subject matter classes. In Arizona, this same segregationist approach was implemented with elementary school children. ELLs were assigned to a prescriptive English language development program and grouped only with other English learners at the same level for four hours a day. They were separated from English-speaking peers and, more important, from subject matter instruction (math, science, social studies). The goal was to accelerate the “learning” of English so that children could pass the required state English Language Proficiency examination after a single year of leveled ESL instruction. According to educational psychologist Patricia Gándara and political scientist Gary Orfield, Arizona was following a model designed by an “obscure educational consultant” whose program focused on “five ELD components within the four hour daily time block: phonology, morphology, syntax, lexicon, and semantics.”7

The extensive analyses that have been conducted on the Arizona program reveal that the three-part test established by the Fifth Circuit Court in 1981 by Castañeda v. Pickard for determining whether a school district program is “appropriate” led to the establishment of the SEI program that deprived ELLs of access to subject matter instruction and resulted in their linguistic isolation.8 These analyses clearly uncover the challenges of providing children English language assistance while at the same time giving them access to the curriculum. They make evident, moreover, the impact of political contexts at particular points in time when, as in this case, opposition to bilingual education led to Propositions 203 in Arizona and 227 in California, measures that required Latinx ELLs to be taught exclusively in English.9

The establishment of language classifications in K–12 schools in the United States and the accompanying practices and mechanisms are relatively recent examples of the ways in which such categories operate and the challenges encountered in their implementation. As useful as classifications are in doing the work of schooling, it is also the case that such classifications can serve as rigid demarcations that exclude particular groups of students, denying them entry and access to educational opportunities and to challenging instruction.

As described above, the category of LTEL is the result of the implementation of such policies and of the well-intended concern expressed by educators, researchers, and other members of the public. However, recent and ongoing research on the impact of this new classification on the lives of already marginalized students (for example, by Maneka Deanna Brooks) provides strong evidence of the negative consequences of academic “sentencing” and “carcerality” of the largest group of ELLs in the country: speakers of Spanish.10 This research points specifically to the “ineffective” teaching of English, the exclusion from opportunities to learn, and the consequences of language assessment practices that determine progress toward students’ reclassification as Fluent English Proficient.11

The “teaching” of languages in instructed settings involves bringing together in a classroom setting a group of learners to “study” and “learn” a language that is new to them. The learners, moreover, outnumber the teacher, the single competent user/speaker of the “target” language. Whether the target language is seen as a social practice or primarily as structure and form, if the goal of instruction is viewed as the development of interactive competence in the language being studied (for example, for immigrant-origin students, the ability to understand teacher explanations, to respond to questions, and to interact with fellow students), the fluent-speaker-to-learner ratio is a particularly serious problem and, to date, an underexamined challenge, resulting in what some have described as adverse and detrimental conditions for the acquisition/development of additional languages.12

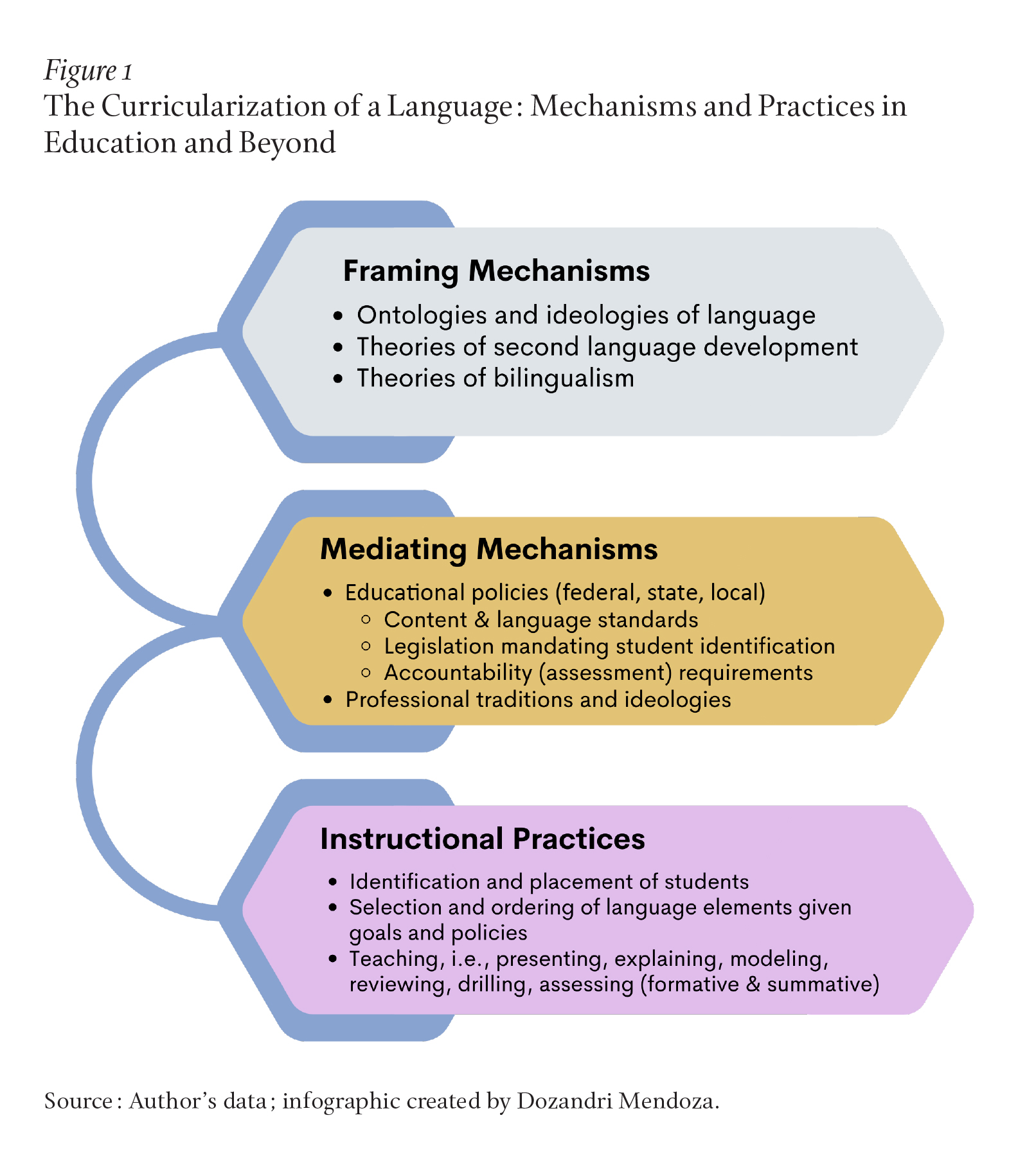

The activity of language teaching in classroom settings, moreover, takes place as part of a complex system that is, for the most part, invisible to its participants. All instructional arrangements that have additional language acquisition as their goal—for example, English as a second language, English as a foreign language, foreign/world language instruction, bilingual education, and content and language integrated learning—are engaged in an activity that has been described as curricularizing language.13 When language is curricularized, it is treated not as a communicative system acquired naturally in the process of primary socialization, but as a subject or sets of skills, the elements of which can be developed through specific types of curricula and controlled experiences. While the activity of “language teaching” itself varies depending on the specific goals and purposes of instructional programs (for example, foreign/world language, heritage language instruction, content-based language instruction), the process of curricularizing language involves a series of levels of interacting mechanisms and elements as illustrated in Figure 1.

The specific activities that count as language instruction take place at the classroom level. Drawing from twenty-five centuries of pedagogical practice in combination with notions of “proficiency” as established by national, state, and local “standards” and listings of learning progressions, the teaching of language in classroom settings inevitably requires a curriculum, that is, an instructional plan that guides the presentation, learning, and assessment of the elements to be “learned.”14 These elements are often presented in a time-honored, accepted order, following either an obvious or more disguised grammatical syllabus usually packaged in published materials, including workbooks and possibly multimedia activities. Whatever the “essentials” are thought to be, instructors “teach” specific elements (such as vocabulary, sentence frames, language forms) that students are expected to “learn” using approaches, materials, and activities that are sanctioned by the schools in which they teach, by the districts in which the schools are located, and by broader state mandates within the larger national system of which they are a part. Instructors carry out the activity of teaching as it is understood by state and national policies and established traditions, bringing to it their own strengths and limitations as well as their own understanding of what teaching language entails. To facilitate their work, teachers generally categorize students as beginners, intermediate, or advanced learners, but, as many practitioners have found, all categories lead to exceptions.

Finally, assessment practices, which are an essential part of classroom instruction, include grades based on the completion of tasks and assignments, as well as student performance on both classroom and officially prescribed student evaluation instruments. Both types of student evaluations are informed by the program’s design as well as by understandings of language development progressions and theoretical perspectives on what needs to be acquired by students when “learning” an additional language.

Macropolicies at the national and state levels, mesopolicies at the school district level, and micropolicies at the school level constrain what teachers do and how they view student progress. For example, currently, the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 requires all states to develop or adopt “English language proficiency standards”: that is, state-consensus documents that put forward the expected language-learning progressions for beginning, intermediate, and advanced English language learners of immigrant background.15 Even though they are the products of consensus activities and not empirically based, these standards documents specify the content of language assessments and directly influence the language teaching enterprise.16

The mechanisms that frame language instruction (that is, the often unexamined ideas that shape the practice of teaching additional languages) include:

- conceptualizations of language;

- ideologies of language, race, class, and identity;

- theories of second-language acquisition/development; and

- theories of bilingualism/multilingualism.

Conceptualizations of language are views and ideas about language as well as definitions of language that are informed by the study of or exposure to established bodies of knowledge. There are many ways that ordinary people as well as linguists define language. Different perspectives on language, moreover, give rise to dramatically different expectations about teaching, learning, and assessing languages. As sociolinguist Paul Seedhouse contends, researchers and practitioners involved in the area of language teaching may not be aware they are starting with vastly different conceptualizations of language and that these differences in conceptualization have led to existing debates in the field.17 The conceptualizations that have informed and continue to inform institutionalized language teaching include notions that various researchers have commented on, including linguists Vivian Cook; Leo van Lier; and Hannele Dufva, Minna Suni, Mari Aro, and Olli-Pekka Salo.18 Many of these notions can be seen as “common sense” (for example, language is a medium of communication), while others are more closely informed by specific theoretical positions (for example, language is a rule-governed system).

Ideologies of language, race, class, and identity inform the entire process of language curricularization and directly influence language education. They inform constructions and conceptualizations of language itself and established and emerging theories of what it means to “acquire” both a first and a second language. Language ideologies intersect in important ways with perspectives on bilingualism and multilingualism, as well as with theories of bi/multilingual acquisition and use. These ideologies—often multiple and conflicting—help compose the institutional and social fabric of a culture, and include “notions of what is ‘true,’ ‘morally good,’ or ‘aesthetically pleasing’ about language, including who speaks and does not speak ‘correctly.’”19 Defined variously as feelings, ideas, conceptions, and cultural models of language, language ideologies may appear to be common sense, but are in fact constructed from specific political economic perspectives and frequently result in evaluative views about speakers and their language use.20

Theories of second-language acquisition/development (SLA) are also important in framing the teaching of additional languages. What is now referred to as mainstream SLA (as contrasted with alternative approaches to SLA) is informed primarily by componential and formalist conceptualizations of language as well as by the disciplines of linguistics and psychology. Until the last two decades, mainstream second-language acquisition has viewed the end-state of additional language learning to be the acquisition of the full monolingual norm said to be characteristic of educated “native speakers.” It has also regarded the process of second-language acquisition as a cognitive phenomenon that takes place in the mind of individual learners. The primary focus of language study has been considered to involve the internalization of the linguistic system (that is, the forms and structures) of the additional language. These theories and perspectives have played an important role in framing the practice of institutionalized language teaching.

Finally, theories of bilingualism/multilingualism are central to both the teaching of additional languages and the assessment systems developed to measure learning/development. Until recently, the field of applied linguistics, and within it the subdiscipline of SLA, had given little attention to bilingualism or multilingualism. The end-state of the acquisition process was seen as the development of the language characteristics of the educated native speaker of the additional language. This native speaker, moreover, was constructed as a monolingual, perhaps the ideal speaker-listener of Chomskyan theory.21 When bilinguals entered the discussion, they were viewed from a monolingualist perspective that overwhelmed the second and foreign-language teaching field, and that constructed “ideal” or “full” bilinguals as two monolinguals in one who are capable of keeping their two internalized language systems (or their two sets of social practices or linguistic resources) completely apart.22 As Dufva, Suni, Aro, and Salo point out, until quite recently, monological thinking dominated the field of applied linguistics and the practice of language teaching.23 Controlled by both established theoretical linguistic perspectives as well as by a written language bias, languages were seen as singular, enclosed systems.24 As a result, involuntary, momentary transfers in language learners that drew from the “other” national language(s) were frowned upon, corrected, and labeled linguistic interference. The use of borrowings and other elements categorized as belonging to another language system were labeled language mixtures (such as Spanglish, Chinglish, and Franglais), and language learners were urged to keep their new language “pure.” They were expected to refrain from “mixing” languages and from engaging in practices typical of competent multilinguals that involve the alternation of (what have been considered to be) two separate and distinct systems.

Much has changed. Monolingualist perspectives have been problematized. The expansion of and increasing epistemological diversity in the field of SLA have led to what some refer to as the “multilingual turn” in applied linguistics and describe as a direct consequence of a growing dissatisfaction with and concern about the tendency to view individuals acquiring a second language as failed native speakers.25 Beginning in the early 1990s, numerous scholars criticized monolingual assumptions and the narrow views of language experience that these perspectives implied.26 Nevertheless, writing many years later, applied linguist Lourdes Ortega contends that mainstream SLA has not yet fully turned away from the comparative fallacy: that is, the concern about deviations from the idealized norm of the additional language produced by language learners.27 She argues, moreover, that in spite of the extensive work carried out on this topic,28 many applied linguists and language educators do not fully understand the ideological or empirical consequences of the native-speaker norms and assumptions they rely upon in their work.

Others are more optimistic. For example, the Douglas Fir Group, a group of distinguished applied linguists and second-language acquisition theorists of various persuasions, contends that a wider range of intellectual traditions and disciplines are now contributing to the field of SLA, leading to a greater focus on the social-local worlds of additional language learners.29 They argue that SLA must be “particularly responsive to the pressing needs of people who learn to live—and in fact do live—with more than one language at various points in their lives, with regard to their education, their multilingual and multiliterate development, social integration, and performance across diverse contexts.”30

While not yet widely represented systematically in the actual practice of language instruction, there has been an extensive expansion and problematization, at the theoretical level, of positions that were previously unquestioned. For example, that language programs teach and students learn specific “national” (named) languages, and that national languages are unitary, autonomous, abstract systems formally represented by rules and items. There is also increasing rejection of the position that, although national languages have different social and regional varieties, the goal of language teaching is to help learners to acquire the norms of the “standard” language as codified by pedagogical grammars and dictionaries. Importantly, the field of applied linguistics itself is being closely examined and in the current context in which there is increasing awareness of the impact of systems of oppression on minoritized peoples, the question is whether there can be a race-neutral applied linguistics: that is, “impervious to the effects of racism, xenophobia, and concerns about language rights.”31

In both current and past discussions about educational policies and practices focusing on the education of students who do not speak a societal language, very little attention has been given to conceptualizations of language itself. In the United States, it has been taken for granted that there is a common, agreed-upon understanding of what languages are, how they work, and why English, as the societal language, needs to be “learned” by students in order to succeed in American schools. Underlying existing classification and assessment policies for students who are categorized as English Language Learners, moreover, are folk perspectives about “good” language or more recently “academic” language that emphasize vocabulary, correct grammar, near-native pronunciation, standardness, and other markers of complexity, accuracy, and fluency understood as “good” usage. Additionally, it has been generally assumed by both educators and policy-makers that for English Language Learners, second-language acquisition follows predictable trajectories that can be accurately measured by standardized tests.

At the same time, for almost five decades, there has been a fundamental paradigm shift in the ways that scholarship in a number of disciplines (such as applied linguistics, psychology, sociolinguistics, anthropology, sociology, communication, cognitive science, usage-based linguistics) now problematize “what is casually called a language.”32 In the second decade of the twenty-first century, cutting-edge scholarship on language in disciplines that directly inform education has undergone a paradigm shift from the tenets of behaviorist psychology and structural linguistics to a more contextualized, meaning-based, social view of language. This shift takes for granted a rethinking of language as object.33 Perspectives on bi/multilingualism, moreover, have shifted from views of “real” or “true” bi/multilinguals as speakers of two named languages (always kept separate) to views of communicative and interactional multicompetence in which individuals deploy resources from their entire repertoire.34

High school students labeled LTELs, who entered the American educational system as young children, have been found to be multicompetent, skilled users of English capable of expressing themselves effectively for a variety of purposes in both spoken and written English.35 Recent research, moreover, has determined that these young people see themselves as fluent and capable speakers of English. They dismiss attempts to “assess” their English on yearly English Language Proficiency examinations and thus rarely make an effort to obtain high scores.

For the field of applied linguistics and for the practice of language education/language teaching, the identification of students as LTELs, however, presents challenges. In theory, applied linguists can provide a race- and class-neutral theoretical framework that can inform the practice of teaching English to LTELs. And yet, as pointed out above, researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners are part of a complex system that constrains their perceptions of both groups of students. Teachers, moreover, are embedded in the same system and deeply influenced by their commitment to doing the “best” for their students. ESL teachers want their students to pass the required state English Language Proficiency examination and to be reclassified as early as possible. Moreover, they want to help LTELs develop the variously described “academic language” that many educators and researchers claim that they do not have and that they believe is essential to their educational futures, social justice, and life success.

For minoritized students and especially for LTELs, every aspect of the educational system that involves them implicates language. Content and language standards, curriculum, pedagogies, and assessments in particular can potentially contribute to or undermine these students’ opportunities to develop their subject matter knowledge and their talents and to maximize their futures. For that reason, when linguistic justice is a goal, it is of vital importance that researchers and practitioners scrutinize the sets of standards (learning progressions) and expectations underlying the language assessment systems currently in use to measure the development and/or the quality of both English and Spanish. Minimally, these standards need to be examined to determine whether they are informed by current scholarship and research about both ontologies and ideologies of language as well as about bi/multilingualism. Standards are important because they establish:

- the ways ELL students are assumed to grow in their use of English over time;

- the language abilities expected at different levels of development;

- the aspects of language that need to be measured in determining progress; and

- the types of support that will be required in order to provide these learners with access to instruction in key subject-matter areas (available exclusively in English).

For such standards to serve the purpose of appropriately supporting and monitoring the growth of English or Spanish language proficiency in minoritized youth, they must be constructed to describe the trajectories that linguistically multicompetent K–12 learners follow in the development of English/Spanish in school settings. Additionally, they must be informed by a clear theoretical position on the ways that instruction can impact (or not) the complex, nonlinear process of language development/acquisition, and they must take into account the fact that there are currently few longitudinal studies of the second-language acquisition process.36 Researchers working from the tradition of corpus linguistics, moreover, argue for authentic collections of learner language as the primary data and the most reliable information about learner’s evolving systems. Drawing from the study of learner corpora, applied linguist Victoria Hasko summarizes the state of the field on the “pace and patterns of changes in global and individual developmental trajectories” as follows:

The amassed body of SLA investigations reveals one fact with absolute clarity: A “typical” L2 developmental profile is an elusive target to portray, as L2 development is not linear or evenly paced and is characterized by complex dynamics of inter- and intra-learner variability, fluctuation, plateaus, and breakthroughs.37

In sum, the state of knowledge about stages of acquisition in second-language (L2) learning does not support precise expectations about the sequence of development of additional languages by a group of students whose proficiency must be assessed and determined by mandated language assessments. Thus, constructing developmental sequences and progressions is very much a minefield.

Assessing language proficiency, moreover, is a complicated endeavor. As applied linguists Glenn Fulcher and Fred Davidson contend, the practice of language testing “makes an assumption that knowledge, skills, and abilities are stable and can be ‘measured’ or ‘assessed.’ It does it in full knowledge that there is error and uncertainty, and wishes to make the extent of the error and uncertainty transparent.”38 And there has been increasing concern within the language testing profession about the degree to which that uncertainty is actually made transparent to test users at all levels as well as the general public. Linguist Elana Shohamy, for example, has raised a number of important issues about the ethics and fairness of language testing with reference to language policy.39 Attention has been given, in particular, to the impact of high-stakes tests, to the uses of language tests for the management of language-related issues in many national settings, and to the special challenges of standards-based testing.40 Applied linguist Alister Cumming makes the following powerful statement about the conceptual foundations of language assessments:

A major dilemma for comprehensive assessments of oracy and literacy are the conceptual foundations on which to base such assessments. On the one hand, each language assessment asserts, at least implicitly, a certain conceptualization of language and of language acquisition by stipulating a normative sequence in which people are expected to gain language proficiency with respect to the content and methods of the test. On the other hand, there is no universally agreed upon theory of language or of language acquisition nor any systematic means of accounting for the great variation in which people need, use, and acquire oral and literate language abilities.41

Accepting the results of current assessments as accurate measures of the language proficiencies of bi/multicompetent students is simply unjust and unacceptable. Tests are not thermometers; they are instruments that allocate educational opportunities and that, as sociolinguists Matthew Knoester and Assaf Meshulam contend, impair the cultural, educational, and personal development of the country’s most vulnerable students.42