The Surge of Young Americans from Minority-White Mixed Families & Its Significance for the Future

The number of youth from mixed majority-minority families, in which one parent is White and the other minority, is surging in the early twenty-first century. This development is challenging both our statistical schemes for measuring ethnicity and race as well as our thinking about their demographic evolution in the near future. This essay summarizes briefly what we know about mixed minority-White Americans and includes data about their growing numbers as well as key social characteristics of children and adults from mixed backgrounds. The essay concludes that this phenomenon highlights weaknesses in our demographic data system as well as in the majority-minority narrative about how American society is changing.

A largely unheralded demographic development holds the potential to reshape the ethnoracial contours of American society in the coming decades. That development is the surge of young people coming from ethnoracially mixed families, and especially from those in which one parent is non-Hispanic White (“White” in what follows) and the other minority, either non-White or Hispanic.

To be sure, mixing across ethnic and racial lines has been a feature of the American experience since the earliest days of European colonization. Mixing between different European origins was celebrated as early as the eighteenth century by Hector St. John de Crèvecouer in Letters from an American Farmer. In the post–World War II period, the rise of marriage on a large scale across ethnic and religious lines among Whites played a leading role in the story of mass assimilation, which forged a White mainstream that included the descendants of late nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century immigrants from Ireland and Southern and Eastern Europe.1 Throughout American history, Whites’ dominant status has been expressed in sexual encounters across racial divisions, particularly between White men and minority women, that have produced children. When these children were mixed White and Black, they were mostly consigned to the African American population by virtue of the so-called one-drop rule. When the children were mixed White and American Indian, they had a greater chance of being absorbed into the White population.2

The mixing across the major boundaries–of race and of Hispanic ethnicity–appears to hold a new significance in the early twenty-first century. The current situation seems novel in the degree of social recognition accorded mixed ethnoracial parentage as an independent status, rather than one that must be amalgamated into one group or another (as in the one-drop rule). The Census Bureau’s important decision to allow multiple-race reporting starting in 2000 is an acknowledgment of this new reality but also has contributed to it by creating statistical data concerning racial mixture that permeate into public consciousness.3

However, the extent and long-run significance of this mixing still elude the stylized demographic “facts” of which Americans are most aware, epitomized in the majority-minority society anticipated by midcentury. In truth, mixing between Whites and minorities presents major challenges to common conceptions of, and census classification schemes for, ethnicity and race. For this reason, the degree of mixing and our ability to discern its societal significance are not reflected clearly in publicly available demographic data.

In this essay, I assess ethnoracial mixing, presenting estimates of its current extent and trend. I also summarize, if all too briefly, what we know about the characteristics of individuals from mixed minority-White family backgrounds, in order to gauge where they appear to locate within American social structures.4 Though the details of this picture are complex, its broad outlines seem apparent. For the most part, individuals from these origins seem to be integrating into what can be described as the “mainstream” of American society, where most Whites are also found. The important exception involves individuals with Black and White parentage, who suffer from the severe racism that still impedes Americans of visible African descent. In the conclusion, I point out the implications of mixing for our demographic understanding of the American near future.

Ethnoracial mixing in families has risen steadily since the late 1960s. Critical to this trend was the wonderfully named 1967 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court Loving v. Virginia, which invalidated the remaining antimiscegenation laws. To be sure, marriages are only a measure of the trend: they do not encompass the entirety of mixing since family connections, such as coparenting, form outside of marriage. But we have good data for marriage. The Pew Research Center has tracked marriages involving partners from two different major ethnoracial categories.5 In 1967, about 3 percent of newlyweds were in intermarriages; by 2015, this rate had risen to 17 percent. It seems highly likely that the rate of mixing in families formed without marriage is at least as high, since one reason that couples do not marry is family opposition, which is usually greater when a partner belongs to a different ethnoracial group. Eighty percent of the mixed marriages of 2015 united a White partner with a minority partner, the largest grouping among them constituted by Hispanic-White couples.6

A consequence of rising mixing in families is, quite obviously, an increase in the fraction of youth who are growing up with parents, as well as numerous other close relatives, from two different ethnoracial groups. We can think of kinship connections that by virtue of birth span major societal boundaries as the sociological essential of a mixed family background. Birth certificates provide the best data about mixed backgrounds in this sense, since they include the children of noncohabiting parents, who may still provide kinship connections for them. In 2018, fathers’ and mothers’ ethnoracial backgrounds were indicated on 87 percent of birth certificates. Birth certificates missing a parent’s information–invariably the father’s–are unlikely to represent mixed parentage since the missing data probably indicate a broken parental connection, so they can be counted among the unmixed. On this basis, 10.8 percent of all the births in 2018 were to mixed minority-White couples. The parents of an additional 3.7 percent of births came from different minority backgrounds.

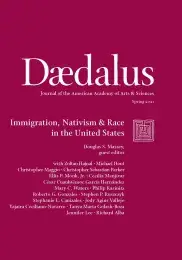

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the mixed infants of 2018 in terms of the ethnoracial origins of the parents.7 The largest single category by far–almost 40 percent of all mixed births, and more than half of all those in which one parent is White–is for infants with one Hispanic parent and one White, non-Hispanic parent (a group I will refer to as “Anglo-Hispanic” or “Hispanic-White”). It is fairly evenly divided between families in which the Hispanic parent is the father and those in which it is the mother. Other large categories of mixed infants with one White parent include: those whose minority parent is Black (and usually the father), amounting to 13.3 percent of all mixed births; those whose minority parent is Asian (and usually the mother), 9.4 percent of all mixed births; and those with a mixed-race parent, 10.4 percent of mixed births. Most of the racially mixed parents have some White (that is, European) ancestry. As we will see, there is a strong tendency for individuals from mixed minority-White backgrounds to choose White partners.

Infants with a White parent are three-quarters of all mixed infants. In the quarter of mixed births involving minority parents only, Hispanics are again central. Infants with one Black parent, usually the father, and one Hispanic parent are 8.5 percent of all mixed births. Infants with one Hispanic parent and one non-Hispanic parent of mixed race are 3.6 percent; and those with one Hispanic parent and one Asian parent are 3.2 percent. Infants with a Black parent, usually the father, and a racially mixed parent are also appreciable in number at 3.9 percent of mixed births. The remaining 6.1 percent are scattered among various combinations of mixed minority origins.

To put the mixing between Whites and minorities into perspective, infants born to a minority-White parent combination are more numerous than those born to two Black parents (9.1 percent of all births). However, when births to Black mothers who are solo parents (that is, no information for fathers is given) are counted in the unmixed Black group, then the unmixed Black group, at 13.6 percent, eclipses the mixed minority-White group. The latter is also smaller than the unmixed Hispanic group, at 19.5 percent of all births. However, no other group of minority babies approaches the mixed minority-White one in size.

Another way of thinking about numerical impact is in terms of the share of births to minority parents that also involve White parents. Consider the Hispanic population in this regard, since it is the largest minority in the United States and projected to increase substantially in size by midcentury. In 2018, 29.1 percent of all births involving Hispanic parents also involved a non-Hispanic parent, and 20.7 percent–one of every five–involved a White parent. Of course, many contemporary Hispanic parents are immigrants, and the rates of mixing are moderately higher when parents are U.S. born. The story is more or less the same for other minority populations. Even for Whites, still the largest ethnoracial population in the United States, the rate of mixing is appreciable: 19.0 percent, or one out of five.

Like the rate of intermarriage, the percentage of all infants with mixed parentage has been rising over time. The best measure we have of this trend comes from census data and must for this reason be limited to infants in households containing both parents. In 1980, just 5 percent of these infants had mixed parentage, and this mixing incidentally was dominated by Anglo-Hispanic couples. In 2017, the equivalent percentage was 16.1 percent, a threefold rise in less than forty years.

It seems certain that the rate of mixing will continue to rise, although it is impossible to say how high it will go. Key demographic features of the immigrant-origin minority populations point in different directions. On the one hand, their rising size over time is likely to dampen somewhat family mixing because larger groups offer more opportunity for in-group partnering. (By the same logic, the declining size of Whites among young adults is consistent with greater mixing for them.) On the other hand, the generational shift away from the immigrants–and especially to the third generation–is strongly associated with family mixing. And, in the case of Hispanics, increasing educational attainment is, too. The population projections of the Census Bureau indicate much greater future mixing between Whites and minorities.8

One great truism of social science is that where we start in life is a very good predictor of where we wind up. And for many children from mixed minority-White backgrounds, their start in life is better than where those with the same minority family origins start, though it is typically not equivalent to where White children begin. The one great exception involves children with one White and one Black parent, who suffer at the start from systemic racism that accompanies them as they grow up.

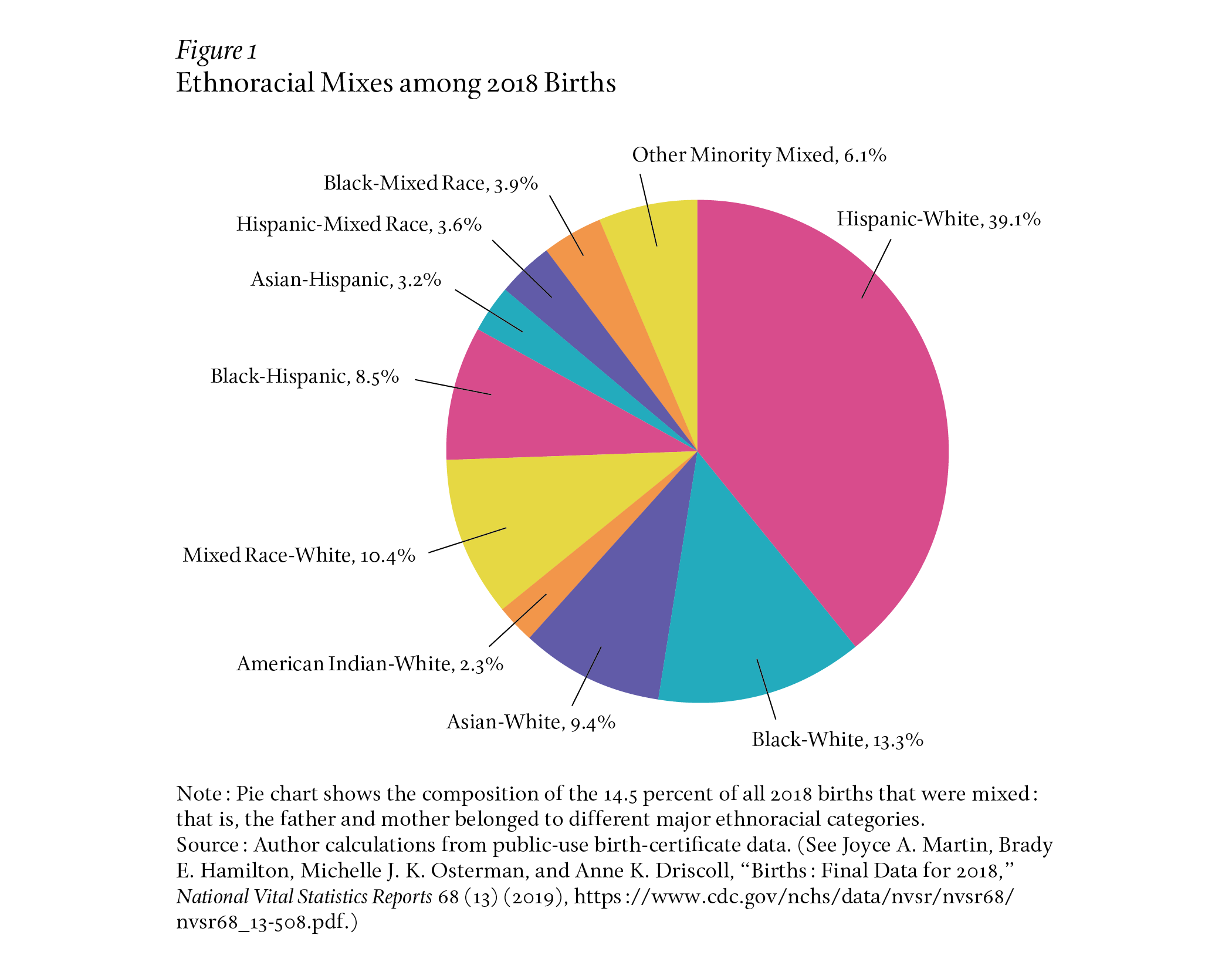

Consider the education of parents, a strong predictor of education in the new generation (see Figure 2). There is a gradient in the parental education of mixed minority-White infants that runs from the children of Asian-White parentage, the most advantaged, to those with a Black father and a White mother, who are dominant among Black-White infants but also the least advantaged mixed group. In the case of the former, the majority of infants have two parents who are college graduates, and for more than half of the rest, one parent graduated from college. In this respect, Asian-White infants enjoy a more favorable start in life than do infants with two White parents, among whom one-third have two college-graduate parents. However, the children of a Black father and a White mother are on average only slightly better off than the children of two Black parents; about 30 percent have at least one parent who completed college. The children of a White father and a Black mother are better off–about 40 percent have a college-educated parent–though their parents average less than the educational level of two White parents.

Two other major categories of minority-White infants are also positioned more favorably than the average infant with minority parents only. About 40 percent of Hispanic-White infants have at least one parent with a college degree; the figure is higher when the White parent is the father. More than 40 percent of infants with a White parent and a racially mixed one have a college-educated parent, and once again the figure is higher when the father is White.

Another revealing aspect of the situation of infants of mixed parentage is where their families reside. Residential disparities in a highly segregated society like the United States are a primary mechanism of transmitting inequality across the generations. School quality, to take an obvious instance, is highly variable, in part because of the predominant role of local and state funding, and tends to correspond with the ethnoracial and socioeconomic composition of local areas.9 To examine the situation of the families of infants included in American Community Survey data, the spatial divisions of the country can be fit into a serviceable, if rough, scheme that takes account of how urban a space is and whether a residence is owned or rented.10 The combination of these two factors maps out socially very different residential spaces in the United States.

Minorities are more likely than Whites to live in urban and inner-suburban areas (abbreviated as “urban” subsequently) that are dominated by rental housing. For instance, nearly half of the families of Black infants live in rental spaces in cities or inner suburbs, but only one-quarter are in owner-occupied homes in suburban areas. The families of White infants are more likely to live in suburban or city-edge areas (abbreviated subsequently as “suburban”) dominated by owner-occupied homes. Nearly half are in homeowner suburban areas, while only 15 percent are urban renters. Another quarter are located in rural areas and small towns, mostly in homes they own.

The families of some categories of mixed minority-White infants are at least as concentrated in homeowner suburban areas as White infants and their families are. This is true, for example, of families in which one parent is White and the other parent is of mixed race. Like Whites, they are also represented in rural areas and small towns. Asian-White families with infants are even more concentrated in homeowner suburban spaces than the families of White infants; however, unlike Whites but like Asian-only families, they are infrequently found outside, or on the edge of, metropolitan regions.

The families of Hispanic-White infants are more likely to reside in homeowner suburban areas than in rental urban ones, but their residential distribution does not favor the former as much as that of White families does. Nevertheless, they are much less located in urban rental spaces than are Black or Hispanic families. In other words, they are closer to White families in terms of residence than they are to the main minority ones. Also in between, but this time closer to a residential distribution like minorities, are Black-White families with infants.

An implication of these patterns is that mixed minority-White children often are located in places that, while they may be diverse, include many White children. Thus, many have White playmates and learn how to relate amicably to Whites, as some Whites do to them. This childhood integration potentially has major implications for adult life, where pathways to socioeconomic success often run through largely White institutions and social worlds. Is the implication corroborated by other data?

We have both qualitative and quantitative evidence to support it. In an analysis of friendship patterns of adolescents, found in the Adolescent Health Survey (Add Health), a rigorously conducted, nationally representative study, sociologist Grace Kao and her colleagues found that some groups of mixed youth frequently chose White best friends. Asian-White adolescents are an example: about 70 percent chose White best friends, and only 11 percent chose Asian ones. The tendency of mixed Asian-White youth to befriend Whites is partly the result of the racial mix of the high schools they attend, which are majority White on average. Hispanic-Whites also seem to have many White best friends, although an inferential step is required to reach this conclusion. The study examined the friendship of racially White Hispanics, among whom most mixed Hispanic-White youth are likely found. The majority of these youth (57 percent) chose White best friends, and another 13 percent chose Hispanic friends who are described as racially White. In this case, the choice pattern mirrors the compositions of the schools attended.11

The pattern looks very different for mixed youth of African descent. Black-White adolescents are much more likely than Asian-White and Hispanic-White youth to choose friends of the same minority origin: about half did so in the Add Health study, though this tendency is markedly lower than that of Black-only adolescents. Only 20 percent chose White best friends. These choices are more concentrated among minority friends than would be expected from the composition of the schools Black-White adolescents attend, which are almost half White.

A qualitative study of young adults by sociologist Hephzibah Strmic-Pawl gives insight into the experiences that lie behind the different friendship patterns of Asian- and Black-Whites.12 The Asian-White interviewees mostly grew up around Whites, and seem to feel that their childhoods were not unusual. They were exposed to forms of microaggression during childhood–jokes about any distinctiveness in their physical appearance or the food they ate–but were generally able to shrug them off. In Strmic-Pawl’s apt characterization, they felt “White enough.” For Black-White young adults, the weight of childhood experience was not so benign. Their interviews convey a sense that managing racism and race-inflected encounters is a major theme throughout their life experience. Strmic-Pawl characterizes this theme as “salient Blackness,” and presumably its development began during childhood.

The surge of individuals from ethnoracially mixed families is mostly a twenty-first-century phenomenon, and, moreover, mixed backgrounds seem to have attained a new social recognition since 2000. These facts imply that our data about adults with mixed backgrounds are less reliable as guides to the near future than are our data about today’s children. Mixed family backgrounds are more unusual among adults, and hence the adults from them may have grown up encouraged by the “one-drop” views of others to think of themselves in terms of a single origin.

There is another problem. In our main demographic data sets, like the American Community Survey, the reporting of mixed ethnoracial origins is selective: that is, the reporting is not consistent, even for the same individual over time; many individuals from mixed backgrounds appear at any one moment in unmixed categories. We have very convincing evidence of this.13 Therefore, in examining the characteristics of those who report mixed backgrounds at any one moment, we are missing many with the same origins who classify themselves in a different ethnoracial category. Moreover, we do not know yet how those we can see in the data differ from those we cannot. A solution to this problem is ancestry tracing: that is, gathering data separately about the mother’s and father’s family origins. However, only a few surveys, especially those by the Pew Research Center, do this, and their samples are not large.

One way of counteracting selectivity in reporting of origins is to expand the range of information we consider. For instance, the American Community Survey has a question about ancestry that is usually not taken into account in ethnoracial classifications. However, it allows us to identify a substantial portion of the otherwise hidden mixed individuals, such as Hispanics who report having ancestry like German or Irish. These are, in other words, persons with mixed Hispanic-White family backgrounds, and the following analysis considers them as such.

For investigating the adult socioeconomic status associated with mixed family backgrounds, the best indicator is educational attainment. That is because, as adults, mixed individuals skew young, and therefore they are concentrated in the early stages of work careers. Educational attainment, especially when it involves college graduation or postbaccalaureate education, is surely predictive of eventual labor-market position.

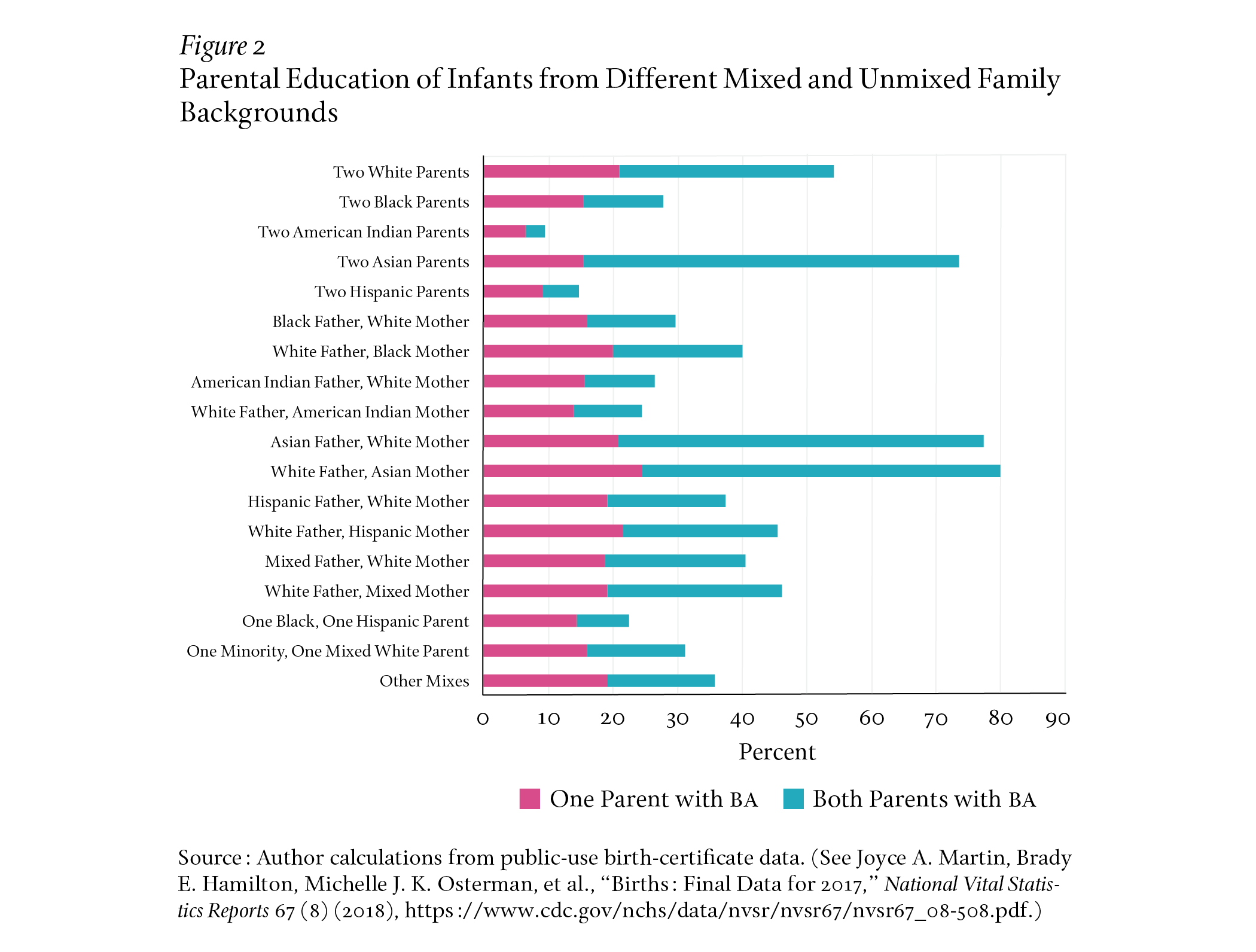

The key finding is that the educational attainment of the major mixed minority-White groups lies in-between that of Whites, whom we can use as a measure of the mainstream pattern, and that of the minority. But it is, on the whole, closer to the White level than the minority one. This pattern can be seen in Figure 3, which presents the educational attainment of major ethnoracially mixed and unmixed categories for U.S.-born men and women between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-nine.

This conclusion is exemplified by the Anglo-Hispanic group. Unmixed Hispanic men (only the U.S. born are considered) have a relatively low rate of baccalaureate attainment, only 16 percent, well behind that of White, or Anglo, men, 37 percent of whom have the credential. Since 30 percent of Anglo-Hispanic men also have graduated from college, they are notably closer to the White percentage than to the Hispanic one. Anglo-Hispanic women are similarly positioned between the White and Hispanic rates, although all the rates of baccalaureate attainment are higher for women.

Individuals who come from Black-White backgrounds occupy a more intermediate position. One-quarter (26 percent) of the men have a college degree, clearly higher than the 17 percent of Black-only men but substantially lower than the 37 percent of White-only men. The educational attainment of Black-White women is similarly situated: 37 percent with baccalaureates or more versus 47 percent for White women and 26 percent for Black women.

Since the expansion of the mixed categories with data from the ancestry question is unlikely to overcome entirely the problem of selectivity, some corroborative evidence would be valuable. It comes from the annual CIRP (Cooperative Institutional Research Program) Freshman Survey, conducted by the University of California, Los Angeles’s Higher Education Research Institute (HERI). In several of the early years of this century (2001–2003), this survey of the nation’s entering college class asked not only about the ethnoracial backgrounds of the students but also about those of their parents, making it possible to identify students with mixed parentage without ambiguity.14

These data demonstrate that, among students with Hispanic ancestry, those with a White parent were more likely to enter a four-year college and much more likely to enter the selective tier of higher education. (A similar pattern, but on a more modest scale, appears for Black students.) The advantage in beginning college becomes apparent when the ratio of Hispanic-only to Anglo-Hispanic students among freshmen at four-year colleges is compared with its equivalent in an appropriate birth cohort. The closest birth cohort is that in the 1980 census, when there were 2.5 Hispanic-only infants for every Anglo-Hispanic infant. Some twenty-plus years later, among first-year college students, there were 1.8 Hispanic-only freshmen for every Anglo-Hispanic freshman–the smaller ratio indicates a disadvantage at that time for Hispanic-only youth in attending college.

More strikingly, students from mixed Hispanic-White families were distributed across the tiers of the four-year college universe similarly to White students. In the early 2000s, more than half (54 percent) of students with two White parents attended colleges that HERI views as more selective, compared with one-quarter (27 percent) of students with two Black parents and one-third (31 percent) of students with two Hispanic parents. However, for students with one White and one Hispanic parent, the fraction in the more selective tier was, at 53 percent, no different from that of Whites. It made no difference whether the Hispanic parent was the father or the mother. Moreover, a White parent was a huge advantage for a student with Hispanic ancestry in gaining access to elite schools, the public and private universities classified by HERI as very selective. About 9 percent of the White-only freshmen attended elite schools in the early 2000s, compared with 5 percent of Black-only students and 6 percent of Hispanic-only students. However, 11 percent of mixed White-Hispanic students attended elite schools. Having a White parent was also an asset in this respect for students with a Black parent.

To understand the social location of mixed Americans, we also need to know about the social milieus with which they typically affiliate: the kinds of friends they have, the neighborhoods where they reside, and the families they form. The Pew Surveys of Multiracial Americans and on Hispanic Identity, which avoid the selectivity problem by ancestry tracing, are informative in this respect.15

One indicator is feeling accepted by Whites, the dominant majority. Sixty-two percent of Asian-Whites feel “very” accepted by Whites, compared with 47 percent who say they feel very accepted by Asians; and 72 percent of Anglo-Hispanics feel very accepted by the White majority, compared with 49 percent by Hispanics. The perceptions of Black-White adults are very different. Only one-quarter of them feel very accepted by Whites, but nearly 60 percent feel very accepted by Blacks.16

Most individuals from mixed minority-White backgrounds, with the prominent exception of those of Black-White parentage, appear to be involved in social milieus that, while varying in their diversity, contain numerous Whites. Nearly half of Asian-Whites say that most or all of their friends are Whites, compared with just 7 percent who say this about Asians. Near two-thirds say that all or most of their neighbors are Whites. The social milieus of Anglo-Hispanics also tilt White, but not as much: half say that all or most of their friends are Whites, while one-quarter say this of Hispanics; and the figures are very similar concerning their neighbors. Individuals who are White and Black are located in quite different social spaces. Half of them say that all or most of their friends are Black. However, just one-third claim to live in mostly Black neighborhoods; this group is outnumbered by the more than 40 percent who live in mostly White neighborhoods.17

Most tellingly, individuals from mixed minority and White family backgrounds appear mostly to marry Whites, on the one hand supporting the notion that Whites make up disproportionate shares of their social milieus and, on the other, ensuring that the next generation, their children, will grow up in heavily White, if still mixed, family contexts. Romantic partners typically are chosen from the people encountered in everyday social environments, such as school or work. High probabilities of marrying Whites indicate that these milieus are preponderantly White, although we cannot discount the possibility that some mixed individuals seek out a White partner because of Whites’ status at the top of the ethnoracial hierarchy.

Based on the expanded definitions of mixed minority-White categories, tabulations from the 2017 American Community Survey, restricted to individuals under the age of forty to capture recent marriage patterns, reveal the tendency to choose White partners. More than 70 percent of Asian-White women are married to White men, and few, only 10 percent, chose Asian-only or Asian-White men. The figures are a bit different for Asian-White men, but not greatly so: 64 percent of them have White partners and less than 20 percent have partners with some Asian parentage. The tendency to marry Whites is not as strong for Anglo-Hispanics, but the majority have White spouses: 60 percent of women and 57 percent of men. About 30 percent in each case are married to someone of whole or part Hispanic heritage.

For those of Black and White parentage, marriage to Whites is–unsurprisingly –less common. But it is much more frequent than is true for individuals from Black-only backgrounds. More than 40 percent of Black-White men have White partners; this figure is higher than the percentage with spouses who are Black only or Black-White. Somewhat more than one-third of Black-White women are married to Whites, a percentage about equal to the fraction with Black-only partners. The expansion of the category through the ancestry data substantially lowers the intermarriage percentage because it brings in many individuals who classify themselves as only Black on the race question. These are individuals who, it appears, are in heavily African American social milieus.

In addition to socioeconomic advancement, as reflected in improved educational life chances, and frequent integration into social milieus containing many Whites, as indicated by high rates of marriage to Whites, one other characteristic of Americans from mixed minority-White backgrounds stands out: the fluidity of their ethnoracial identities. This fluidity, which entails presenting oneself sometimes as mixed and at other times in terms of a single part of one’s background, may also imply contingency: that is, identifying oneself in a way that fits the situation of the moment. But we do not have sufficient evidence at this point to confirm this.

The evidence we have of fluidity is compelling and shows that mixed individuals do not present consistently in terms of the broad ethnoracial categories of the census. One study, based on a match of individuals between the 2000 and 2010 censuses, provides a powerful demonstration.18 Overall, 6 percent of individuals presented inconsistent ethnoracial reports, but for those who indicated mixed origins on one or both censuses, the rate was much higher. Of those who are Asian and White by race on one of the censuses, for instance, barely more than one-third (34.5 percent) are consistent on the other. Of the nearly two-thirds who are inconsistent, the great majority report as single-race Asian or White on the other census, with White responses outnumbering Asian ones by 60 percent. The inconsistency pattern among individuals who are Black and White on one census is rather similar, except that Black-only responses outnumber White-only ones on the other census by a two-to-one margin.

Another study that makes use of matched census data (over three time points) reveals fluidity in the identities of individuals who are part Hispanic and part something else.19 This analysis found that 14 percent of individuals with discernable Hispanic ancestry did not report consistently as Hispanic. This figure is deceptively low because the base for the percentage includes the large population of Latin American immigrants, for whom the rate of inconsistency is very low. Among those who appear consistently as Hispanic, the percentage having some non-Hispanic ancestry is small, about 5 percent. Among those who are inconsistent, the percentage is roughly ten times higher.

For Hispanics, we have additional evidence that mixed family backgrounds are connected to a weakening of Hispanic identity. Confirmation comes from the Pew Survey of Hispanic Identity, which found that 11 percent of individuals with Hispanic ancestry did not identify as Hispanic; almost all of them came from mixed family backgrounds. Among those from mixed backgrounds who did identify as Hispanic, more than 40 percent said that they most often described themselves as “American,” a figure that was more than three times higher than that for unmixed Hispanics.20

A widely believed narrative about the American future, anchored in demographic data and projections, holds that, within a few decades, Whites will become a minority of the American population, outnumbered by the aggregate of minority groups. This narrative has been dubbed the “majority-minority society,” and it is generally presumed that this future demographic shift will have profound consequences for the distribution of cultural, economic, and political power among the nation’s ethnoracial groups.

But the surge of young Americans from mixed minority-White backgrounds complicates this narrative, if it does not overturn it. One reason is that the publicly disseminated demographic data, which serve to justify the majority-minority narrative, inadequately reflect mixed backgrounds. This inadequacy has to do with problems in conventional ethnoracial classifications. For one thing, in publicly presented data, the Census Bureau usually classifies all individuals who report themselves as mixed on the race question in a separate “mixed race” category. The members of this category are treated as non-Whites in interpretations of the data, although the great majority of them have a White parent. For another, the measurement of ethnoracial origins in the current two-question format–one for race, the other for Hispanic origin–leads to the classification of anyone who indicates a Hispanic identity as non-White (because “Hispanics may be of any race,” according to the standard demographic formulation). However, we can now be sure that a substantial minority of Hispanics comes from mixed Anglo-Hispanic families; these individuals are lost from view in conventional demographic ethnoracial categories.

The problems with the majority-minority narrative are not just a matter of data–they are also conceptual. The narrative envisions American society as fractured into two separate, competing ethnoracial blocs, one of which is declining while the other is ascending. These blocs are presumed to be distinct in numerous ways having to do with the average social locations of their members, their typical experiences, their views, and above all their sense of relative status. It is widely believed that the ascent of the minority bloc to majority status, which is supposedly driven by inevitable demographic processes, will overturn an established social order in which Whites represent the dominant social group.

The rise of mixing in families between Whites and minorities and the surge of young Americans from mixed minority-White backgrounds calls for new ways of thinking about the social changes taking place as a result of increasing societal diversity. This mixing is not at all acknowledged in the majority-minority narrative, a sign of the problematic conceptualization it entails. At the most fundamental level, mixing is reducing the separateness of the ethnoracial blocs: the share of the White bloc with a sense of membership in the minority bloc, along with deep connections to minority individuals, will continue to grow in the near future; and the same will be true for the shares of minority groups with a degree of membership in and close relationships to individuals in the White bloc. For many, what is viewed today as a bright divide in the majority-minority narrative will increasingly blur.

The limitations of the majority-minority narrative betray problems in social-science theorizing about American society. In recent decades, thinking about race and ethnicity has been dominated by critical race theory, at whose core is a vision of society as organized in terms of a rigid ethnoracial hierarchy, which is maintained for the benefit of the dominant group, Whites. Critical race theory has, without question, generated many important insights into ethnoracial inequalities. But the surge of young Americans with mixed family backgrounds, many of whom appear to be integrating into the mainstream, where most Whites are also located, demonstrates that current developments in the United States cannot be understood solely on the basis of critical race theory.

We need another kind of idea, one that has been salient at various points in American history and at whose core is the notion of assimilation. Assimilation theorizing, like critical race theory, envisions society in terms of an ethnoracial hierarchy, but with more fluidity. Its most important insights are focused on the ways that individuals and even groups can improve their position in this hierarchy, even reaching parity and integrating with the dominant group. We have undeniable evidence that assimilation was the paramount process among the descendants of early-twentieth-century immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. The evidence about twenty-first-century mixing across the majority-minority divide indicates that it is relevant to at least some descendants of post-1965 immigrants. It is time for assimilation thinking to make a comeback.