Syria & the CNN Effect: What Role Does the Media Play in Policy-Making?

Syria’s devastating war unfolds during unprecedented flows of imagery on social media, testing in new ways the media’s influence on decision-makers. Three decades ago, the concept of a “CNN Effect” was coined to explain what was seen as the power of real-time television reporting to drive responses to humanitarian crises. This essay explores the role traditional and new media played in U.S. policy-making during Syria’s crisis, including two major poison gas attacks. President Obama stepped back from the targeted air strikes later launched by President Trump after grisly images emerged on social media. But Trump’s limited action did not shift policy. Interviews with Obama’s senior advisors underline that the media do not drive strategy, but they play a significant role. During the Syrian crisis, the media formed part of what officials describe as constant pressure from many actors to respond, which they say led to policy failures. Syria’s conflict is a cautionary tale.

The devastating conflict in Syria has again brought into sharp focus the complex relationship between the media and interventions in civil wars in response to grave humanitarian crises. Syria’s destructive war, often called the greatest human disaster of the twenty-first century, unfolds at a time of unparalleled flows of imagery and information. It is testing in unprecedented ways the media’s influence on decision-makers to drive them to take action to change the course of a bloody confrontation or ease immense human suffering.

One after another, year after year, veteran envoys and human rights defenders decry the failure of world powers to stop what they describe as the worst of abuses and impunity they’ve seen in lifetimes of working on major conflicts and humanitarian catastrophes. Journalists have also expressed their frustration and disbelief. “You would hope that by doing reports and putting them on TV and that talking about them that people would wake up, they would see, they would feel, and maybe call for action, and the calls are being made, but the action isn’t being taken,” lamented NBC’s Chief Foreign Correspondent Richard Engels. He spoke as a haunting image emerged of a stunned five-year-old Syrian child, Omran Daqneesh, sitting alone in an ambulance, covered in dust and blood, during some of the worst battles for the northern city of Aleppo in late 2016.1 The photograph was widely reported, went viral on social media, and was invoked by world leaders including President Obama. But it also became a focus of intense scrutiny in a highly politicized news and information landscape. And it was one of only a handful of images that broke through what has been a nonstop, numbing flow of distressing imagery on social media emerging from Syria since protests calling for political change first erupted in March 2011.

Nearly three decades ago, the term CNN Effect was coined. It became snappy shorthand and an academic paradigm to explain how new, real-time reporting on U.S. television networks was driving Western responses, mainly by the military, to humanitarian crises around the world. Since then, dramatic changes in the media landscape, galvanized by technological and political change, created new concepts such as the “Al Jazeera Effect” and the “YouTube Effect.” 2 Extensive scholarly research has concluded that this notion of a mighty media is a myth or hyperbole.3 But it has also underscored that this does not mean the effect is nonexistent.

Both Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama faced images of major Syrian poison gas attacks in rebel-held areas that were filmed by local activists, posted on social media, and reported worldwide. Trump and Obama would seem to provide two cases to explore some of the theory and research around the concept of a CNN Effect. These two decision-makers–one who prides himself on watching a lot of television, and another who says he deliberately does not–responded in different ways. But, in the end, it confirms that the CNN Effect, when it exists, is not decisive. President Trump’s decision to launch targeted air strikes turned out to be a one-off: they did not shift overall policy on Syria nor did they significantly change the situation on the ground. But interviews with senior U.S. policy-makers–mainly from the Obama administration, which was in office for much of the Syrian crisis–underline that, while the media do not determine policy, they do play a key role. While Obama pulled back from launching air strikes in 2013, years of harrowing imagery emerging from the conflict kept Syria on the agenda. They formed part of what senior advisors described as constant pressure emanating from the media and amplified by an array of other actors to “do something.” That, they maintain, led to some policy responses that Obama did not fully support and that, in the long run, failed. This included the covert program to arm and train what were regarded as moderate rebel forces to take on the Syrian military and its allies: Obama doubted it would succeed; his critics say there was never a coherent strategy.

Syria’s war is arguably the first “social media war.” Security risks and visa restrictions often kept many of the world’s leading media, including most mainstream Western broadcasters, off the frontlines. That led to a reliance on streams of information on social media provided mainly by activists. There was often valuable material, but it was hard to verify and, at times, turned out to be wrong or misleading. Battles over “truth” were also fueled by Western government funding of media operations for what it promoted as a moderate armed opposition. On the other side, Russian state propaganda pushed a narrative in support of President Bashar al-Assad’s forces.

Syria is also the most tangled geopolitical conflict of our time. The West, Arab states, and Turkey have provided significant military support to an array of rebel fighters including hard-line Islamists. Russia and Iran-backed militias bolstered Syrian government forces with formidable firepower. There have been many agendas, no easy answers, and no consensus on a way out of the crisis. A spiral into appalling violence has left more than half of Syria’s postwar population displaced, dead, or a refugee in the biggest human exodus in decades.

In what follows, I will illustrate the way the CNN Effect still has some purchase on policy. But this depends greatly on the wider strategic context, dominant thinking about how to respond to mass violence, and on decision-makers themselves. This essay will first briefly explore the impact of the media in the Trump and Obama administrations. Later sections will highlight some critical facets of today’s news and information landscape, including observations from my own reporting from Syria at key moments of this war.

“I tell you that attack on children yesterday had a big impact on me–big impact.”4 That was how President Donald Trump described his reaction to what he had been “watching and seeing” on American cable news networks. A day earlier, distressing images began to emerge from the scene of a poison gas attack in the rebel-held Syrian village of Khan Sheikhoun. Media activists were posting the first ghastly images of stricken women and children on social media. Sixty-three hours later, Commander in Chief Donald Trump ordered an air strike, involving dozens of Tomahawk missiles, on Syria’s Shayrat airfield. It marked the first time the United States had directly targeted a military asset of President Assad. Six years of disturbing images, including grisly scenes from another major chemical attack on the outskirts of Damascus in August 2013, had not pushed President Barack Obama to escalate the United States’ military involvement in this way. Scholars have highlighted how decision-making on major issues “involves myriad factors, ranging from the configuration of the international system to the attributes of individual decision-makers with ‘societal variables’ [including the media] located somewhere in between.”5

President Trump declared that he was launching military action “to end the slaughter and bloodshed in Syria.” President Obama had earlier turned to diplomacy, brokered by Russia, to remove chemical weapons from a volatile country believed to have one of the world’s largest arsenals of this deadly material. But both actions focused on this one significant threat. President Trump’s team then reverted to the broad outlines of the Syria policy that emerged in the latter years of President Obama’s second term: a focus on defeating the extremist Islamic State now regarded as a global threat; a move away from arming and training an increasingly marginalized moderate rebel force; and a recognition that, despite years of grinding war, President Assad wasn’t about to stand down, or be toppled.

At first, the air strikes appeared as a dramatic shift. They were widely hailed across the U.S. political spectrum, aside from the President’s far-right constituency, who denounced it as a betrayal of his “America First” policy. Even leading members of President Obama’s team, who argued for air strikes in 2013, expressed support. So did some prominent American journalists as well as Syrian activists and Gulf Arab allies. All had been intensely critical of President Obama’s reluctance to be drawn into direct military action or to provide more advanced weaponry as part of what was reported to be a $1 billion-a-year covert CIA program to arm and train mainstream rebels, which included some oversight of significant military support provided by Arab and Turkish allies.

“What Syria should teach you is that Trump is the President most vulnerable to the ‘CNN effect’–because he watches so much cable news,” wrote Daniel Drezner (Professor of International Politics at Tufts University) on Twitter. He reiterated his point in a second post: “Most empirical studies of the CNN Effect haven’t found much evidence for it–but I guarantee you it explains Trump’s actions in Syria.”6 Other reactions on social media pointed out that it should be called the “Fox Effect,” in reference to the president’s known viewing preferences. He was reported to have first seen the gruesome images on the Fox Television Network’s morning news show “Fox and Friends.”

Whatever the term, a leader in the White House now seemed to fit the decades-old notion of a CNN Effect: a president, driven by disturbing television images, orders military action in response to an atrocity. It broke, not only with his predecessor’s approach, but also with his own. When President Obama contemplated military strikes in the summer of 2013, the then-business tycoon with political ambitions repeatedly posted on his Twitter: “Do not attack Syria.” Now President Trump has announced that his “attitude toward Syria and Assad has changed very much.” Only a week before, members of his fledgling administration made clear that trying to topple the Syrian President was not an American priority. Now there were statements that “the future of Assad is uncertain, clearly.”7

More than any other branch of U.S. decision-making, the president’s authority to deploy military force unilaterally in the national interest is seen to reflect, in part, the character of the incumbent. Aides to Hillary Clinton spoke of how, had she won the presidency, she would also have been more affected by media coverage on Syria than President Obama, who prided himself on resisting decision-making “based on emotion.” She is also known to have argued for stronger U.S. military involvement when she was Secretary of State to help remove President Assad from power. A national security advisor who worked with both President Obama and President Bill Clinton reflected that the latter was also “much more reactive to press coverage, among other things.”8

President Trump is at another extreme. Much has been written about his attention, verging on obsession, to how the media portray him. He makes no secret that he watches “plenty of television” and famously boasted when he entered the White House that he didn’t need daily intelligence briefings. Anecdotal evidence points to how, after the Khan Sheikhoun poison gas attack, he “repeatedly brought up the photographs.”9 His son Eric spoke of how his sister Ivanka had also influenced her father’s decision to take military action after seeing “this horrible stuff.”10 In what was being widely described as a chaotic White House, advisors ranging from neophytes to battle-hardened military generals, as well as right-wing populists, were all weighing in.

Extensive studies have highlighted how powerful images can only make a real difference in the choices of decision-makers if an avenue already exists for them to act. As strong as the impact of “seeing is believing” is, in the realm of politics and diplomacy, “believing is seeing” can be a more potent force. Journalist Marvin Kalb, who has long focused on the impact of the media, has observed: “Image in and of itself does not drive policy. . . . Image heightens existing factors.”11

This was a president who wanted to respond, and be seen to do so. And he was presented with military options that “would be sufficient to send a signal–but not so large as to risk escalating the conflict.”12 Leading members of Trump’s national security team also believed that Obama had eroded the power of U.S. deterrence by not responding with direct military action when his own “red line” on the use of chemical weapons was crossed in 2013.13 The United States said it was convinced by intelligence showing that “the Syrian regime conducted a chemical weapons attack, using the nerve agent sarin, against their own people.” A UN investigation later reached the same conclusion. Syria and Russia still question the evidence, as does a group of British and American scholars and journalists critical of Western policy.14

Whatever President Trump’s concern for the people of Syria, he also appeared driven to set himself apart from his predecessor’s legacy. Accounts in the media said he also kept mentioning how President Obama looked “weak, just so, so weak,” after the 2013 poison gas attack.15 President Trump was also in search of success stories as he headed toward the one hundred-day marker of his embattled presidency. As security analyst Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer has pointed out in his writing on the CNN Effect and military intervention: “when a state intervenes, it is rarely disinterested.”16 From this perspective, Trump is seen as exploiting the images, rather than responding to them.

Research also shows that the media’s greatest impact on policy is when they can help “determine a policy which is not determined.”17 President Trump’s ideas on Syria were still inchoate. The only part that seemed clear was his emphasis on fighting extremist groups and working with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, a strongman whom he unfailingly held in high regard. While the air strikes were condemned by Russia as a “significant blow” to the relationship, their impact was short-lived.

Despite President Trump’s assertion that he had changed his mind about President Assad and Syria, it became clear this was a one-off. Since April 2017, there have been repeated reports of other chemical attacks, albeit smaller in scale. In one instance, in June 2017, Washington sent a public warning of a “heavy price” if the April attack was repeated. An earlier statement by the White House Press Secretary that deadly barrel bombs, being dropped from Syrian warplanes with devastating effect, would not be tolerated went nowhere. Even more, the cia’s covert program was quietly canceled. It had become increasingly clear, even during Obama’s last years, that is was failing in its ambition to arm and train an effective rebel force to fight against President Assad’s military and allies. As communications scholar Babak Bahador, who studied the impact of the CNN Effect on responses to massacres in the Kosovo war, has observed: “unexpected and emotive images can rapidly open policy windows of opportunity.”18 But they can also close, just as quickly.

The air strikes on the Syrian airfield fit the pattern that has emerged from extensive empirical and analytical research into the CNN Effect. The term was coined during the 1990–1991 Gulf War when dramatic advances in technology made it possible for the United States’ Cable News Network to broadcast live reports around the clock and around the world. Raw, real-time images and instant analysis flashed from frontlines and briefing rooms. Suddenly, it seemed, there was a new and powerful pressure on policy-makers to respond. Heartrending images were seen to have influenced President George Bush’s decision to set up a safe haven and a no-fly zone in 1991 to protect Iraqi Kurds. A year later, reports of starving Somalis played a part in persuading President Bush to send in U.S. forces. And shocking television footage of alleged war crimes in Bosnia and Kosovo were viewed as decisive factors in actions by Western militaries.

But this first “rough draft of history” was soon clarified. Journalist Nik Gowing’s extensive interviews with decision-makers in the Bosnian war concluded that media pressure had not led to any major strategic shifts by Western powers. But they did galvanize a series of more limited “tactical and cosmetic” steps. This included, for example, airlifting children out of a conflict zone or air strikes targeting artillery positions of Bosnian Serb nationalists.19 A broader analysis of President Bush’s 1991 decision to provide a safe zone for Kurds in northern Iraq by media studies scholar Piers Robinson also underscored that compelling coverage was not the only driver, and not likely the main one. U.S. concern that a flood of Iraqi Kurds into Turkey could be destabilizing for a NATO ally was also a critical consideration.20

Crucially, this perception of the media’s emerging muscle had dovetailed with a shift in strategic thinking among Western powers. In the 1990s, this new liberal approach was known as “humanitarian intervention.” Its critics viewed it as a pretext for military intervention in the name of preventing abuses while its proponents welcomed changes in the dominant discourse, which incorporated an emphasis on human rights and humanitarianism.21 It fueled military missions in conflicts such as Northern Iraq, Somalia, and Kosovo.22 The U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 was then launched under the banner of the “war on terror.” But other concepts emerged; in Iraq and Afghanistan, they included “nation-building,” which also involved a focus on elections.

Western leaders now emphasize that “those days are over.” This is both a reflection of years of policy failures in the Middle East as well as a shifting world order, which has seen diminishing space for unilateral Western action. It bears noting, however, that unlike earlier civil wars in the 1990s that gave rise to the discussion of the CNN Effect, in subsequent crises including Syria, the United States was already involved militarily and was, therefore, a player in a war that was also a deepening humanitarian tragedy. The constant question in Syria was over the scope and scale of military intervention.

During most of the Syrian crisis, President Obama was determined not to be drawn into a major military escalation in what he saw as another Middle East quagmire. Any pressure from the media was part of what he called, derisorily, “the Washington Playbook.”23 He described it as “a playbook that comes out of the foreign policy establishment. And the playbook prescribes responses to different events and these responses tend to be militarized responses.” For him, his response to the devastating poison gas attack in Damascus in 2013 marked the moment he dramatically broke with it.

It was a defining moment for Obama’s Syria policy. His critics, including members of his own administration, saw it as a disastrous retreat when he did not reinforce, militarily, his “red line” on the use of chemical weapons. They argue that it cleared the way for Russia’s major military intervention in September 2015 to bolster the flagging Syrian army and also damaged U.S. prestige in the region. But pressure on the Syria policy was not confined to this one dramatic moment. Obama’s advisors speak of constant pressure throughout much of his presidency. “There was pressure on the president coming from various quarters,” said Rob Malley, who served as Special Assistant to the President and White House Coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and Gulf region. “The press, understandably, was depicting the suffering of victims of the regime, which Congress then echoed, as did a number of foreign countries and many, if not most, of his own cabinet.”24

It was this kind of pressure on policy-making, emanating from real-time television coverage, that gave rise to the CNN Effect in the 1990s. Syria’s crisis has unfolded during the proliferation of social media, which is widely picked up by mainstream media. Officials say it intensified this immediacy. In the words of Ben Rhodes, Obama’s Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications, it “brought some of the horrors of war closer to home than past wars.”25 Some senior advisors now say this unrelenting pressure did eventually lead Obama to pursue policies in support of Syrian rebels that he did not fully believe in and that, in the long run, failed.

Obama’s address to the nation on August 31 shot around the world. To the surprise if not shock of some of his closest advisors and allies, he announced that he had decided to postpone any military action and first seek authorization from what he knew was a deeply skeptical Congress. In a speech that followed on September 10, the president invoked grisly images from the poison gas attack in the Ghouta suburb of Damascus, filmed by activists and broadcast by media worldwide, including U.S. television networks. “I’d ask every member of Congress and those of you watching at home tonight to view those videos of the attack, and then ask, what kind of world will we live in if the United States of America sees a dictator brazenly violate international law with poison gas and we choose to look the other way?”26 But it wasn’t television that alerted him; it was horrific imagery on social media that emerged within days of the attack. Rhodes recalled how “some footage made its way out of children suffering the effect of sarin gas . . . and that was on his mind.”27

President Obama has often spoken of how–unlike President Trump–he didn’t turn to television for his news and analysis. “I’m still not watching television, which is just a general rule that I’ve maintained for the last eight years,” he told the The New Yorker’s David Remnick in 2016. He argued that this “is part of how you stay focused on the task, as opposed to worrying about the noise.”28 But, like most decision-makers, Obama was acutely aware of the challenge posed by this incessant flow of information. “If you were president fifty years ago, the tragedy in Syria might not even penetrate what the American people were thinking about on a day-to-day basis. Today, they’re seeing vivid images of a child in the aftermath of a bombing.”29

The president’s aides say he was determined not to be swayed by what he saw as emotional reactions to media coverage. That resistance was said to be shared by some of his closest advisors, including his National Security Advisor Susan Rice. Others, including Secretary of State John Kerry, were described as “more sensitive and receptive” to negative press coverage.30 “I certainly understand that the president has said he’s not influenced by the media on Syria because the mainstream media has been almost uniformly critical of him,” reflected Anne Patterson, former Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs.31

The president also disagreed with many key members of his own team. Senior U.S. officials, including both Secretaries of State Clinton and Kerry, had argued that targeted military interventions at specific junctures could have shifted the military and political balance, especially at junctures when President Assad’s forces appeared to be at their weakest. That view was challenged by others. They assessed that whatever military action Washington and its allies would take, Russia and Iran were prepared to do even more and would set the United States on a “slippery slope.” It was also becoming clear that, unlike Arab leaders forced from power during the unprecedented protests known as the “Arab Spring,” President Assad was drawing strength from loyal supporters inside his country. He was determined to remain in power, whatever the cost.

There was also an acute recognition that the American public was weary and wary of war. Costly and questionable missions, particularly in Iraq, had drained support. In the month after the 2013 chemical attack, most polls found clear majorities opposing U.S. missile strikes in Syria. A majority did not agree that the United States’ vital interests were at stake. Gallup Polls noted that it was “among the lowest” figure of support “for any intervention Gallup has asked about in the last 20 years.”32

But the figures stand in contrast with the polling after President Trump’s air strikes in 2017. Pollsters speak of a “rally effect” when leaders take action. This was witnessed in survey results before and after President Bill Clinton launched air strikes in Serbia in 1999. The same effect was tracked before and after President Obama gave the go-ahead for U.S. participation in the NATO air campaign in Libya. But in Syria, polling shows the “bounce” for President Trump did not last long.33

Interviews with President Obama’s advisors and prominent journalists with access to him underline that, as he weighed military options, he always asked: “how does this end?” The West had already seen the unpredictable consequences of their actions in bringing about regime change in Afghanistan, Iraq, and then Libya. President Obama took the decision in 2011 to call on President Assad to step down. Then, through the rest of his presidency, he deliberated over military and diplomatic options to achieve that on the battlefield and at the negotiating table. “The president struggled with Syria in a way I didn’t see him struggle with any other issue,” said Malley. The lessons of Iraq were said to be uppermost in his thinking. “The cost of not thinking through second-order consequences and the hubris of thinking that our superior military power automatically translated into superior political influence was very much on his mind,” explained Malley.34

The results of President Trump’s air strikes would only confirm his doubt that “a pinprick strike . . . would have been decisive,” even in its limited objective.35 The president’s stance was backed by his top military advisors. “So if we get more involved militarily in Syria, does that mean we should also get involved in Congo?” a senior officer at U.S. Central Command asked rhetorically.36 Critics argued that Syria’s deepening humanitarian disaster, including a massive refugee crisis, was being driven by the brutal force deployed by the Syrian military and its allies. They demanded a more forceful U.S. response. The hard-nosed assessment by many in the U.S. military was that, aside from the global threat posed by the Islamic State, others had far greater strategic interests in Syria. Russia was not only determined to protect its major airfield and naval port, but also its projection of military power, which boosted its role at the world’s top tables. Iran, with its growing sway in neighboring Iraq and ties to Lebanon’s Hezbollah movement, saw Syria as a crucial bridgehead. Assad’s allies also resolved to prevent the West from engineering regime change in Damascus.

Senior officials, including Secretary Kerry, underscore that the president did initially back targeted air strikes in 2013. Many factors, including the media, are said to have played a part in that. This situation underlines the difficulty of disentangling the many inputs into decision-making. Often the media play an indirect role through their influence on politicians and the public, who increasingly rely on new social media platforms, rather than traditional media, for their news.37 And Syria was often the leading foreign policy issue for U.S. allies, aid agencies, and human rights organizations.

“The facts themselves, with more than a thousand dead, were enough to justify action,” said Philip Gordon, who served as the president’s Special Assistant for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Persian Gulf region at the time. But “pictures of innocents and children choking, broadcast throughout the United States, and all over the world, galvanized the feeling and created even more pressure to do something about it.”38 Gordon provides insight into what, in the end, led the president to pull back from military action in 2013 and seek Congressional backing. “His legal advisor Kathy Ruemmler told him he had constitutional authority to act as Commander in Chief. But she also reminded him that during his election campaign his view was he should also get legislative backing.” That seemed to matter to a former professor of constitutional law.

Secretary Kerry told me in an interview that the British Parliament’s vote against military action in Syria, taken just the day before, also had a “profound impact.”39 Prime Minister David Cameron is said to have explained to President Obama in a telephone conversation that it came down to Iraq. In other words, a searing rebuke from politicians and the public over the way faulty intelligence was exaggerated to pave the way for the 2003 military invasion. But, in the end, Secretary Kerry concurred with the president’s decision. He maintains that negotiations, brokered by Russia, to remove Syria’s declared chemical weapons was an effective response, even if it is now clear that some stocks were left behind and reportedly used again.

Every senior policy-maker interviewed for this essay emphasized that, while the media did not determine policy throughout the Syrian conflict, they did play a decisive role. They kept the issue on policy-makers’ desks. It’s what media scholars refer to as “agenda setting” or an “accelerating effect.”40 As U.S. State Department spokesman John Kirby put it: “it propelled the process of exploring options a bit faster.”41

Others see that accelerating speed as consequential, especially in an age increasingly dominated by social media that is often picked up by more traditional media. “The precious moment between the event and the knowledge of the event during which time one can digest, reflect, and plan simply doesn’t exist anymore,” said Malley.42 It also robs policy-makers of the time needed to confirm what is often raw, unverified imagery. And, in Syria, social media was an instrument of information as well as a tool of propaganda, used by all sides.

Like other officials, Malley pointed to positive aspects of valid, real-time information including greater transparency and accountability. Several advisors underlined that it was not an issue of blaming the media, but of understanding what they saw as a new environment confronting policy-makers. Anne Patterson noted: “The first thing people do at 5:00 a.m. is read the mainstream media because that’s really what matters in Washington. By the time people get to work, they have to react to how our policy is reflected in the press.”43 The president’s aides say more time was spent on Syria than any other foreign policy issue. “I can’t tell you how many papers have been written on the legal implications of the responsibility to protect, does it apply to us, and under what circumstances it was relevant,” Patterson recalled. “But it’s all in the margins because the real issue came down to American military intervention.”44 Rhodes adds that, “in Syria, the president was under constant pressure to act. But he felt it was pressure without a full characterization of the risks involved in options like arming the rebels or establishing a no-fly zone.”

That pressure, including repeated questions from Congress, foreign allies, officials, and journalists, meant officials felt they had to respond in some way. “It does drive you to need to be able to do something,” admitted one of the president’s senior advisors. One official cited the “fiasco of the training program” that “allowed the government to point to something and say ‘we’re training a moderate opposition.’” In 2012, leading members of Obama’s team, including Secretary Clinton and CIA Director General David Petraeus, are known to have argued for more military support to strengthen moderate rebels. Clinton later said the failure to build a strong rebel force “left a big vacuum, which the jihadists have now filled.”45 Obama had always expressed doubt that what he called “an opposition made up of former doctors, farmers, pharmacists, and so forth” could defeat “a well-armed state” supported by Russia and Iran-backed militias.46 In Syria’s tangled war, there are many reasons for the program’s failure. But for some of Obama’s advisors, it was a cautionary tale. Despite Obama’s doubts, officials speaking off the record say he authorized the cia’s covert program to try to achieve a number of goals. These included helping the rebels to protect themselves and trying to curb the rise of more hard-line Islamist groups supported militarily by some Arab allies. In the long run, the program failed and was later canceled soon after Trump took office.

Other nonmilitary options were pursued, including largely futile UN-brokered negotiations between the warring sides. Secretary Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov wrangled over cease-fires and humanitarian pauses, anything to get desperately needed relief to millions of Syrians. But the president’s decision to not enforce his “red line” in August 2013 had significant consequences. Kerry admitted that, without a credible threat of force, he had little leverage.47 And furious Gulf Arab allies started funneling support to whichever rebel groups showed success on the battlefield, which strengthened hard-line Islamist groups the West did not want to support.Several officials used the same phrase to describe the U.S. military and political responses: it “ended up doing just enough to keep the war going but not enough to end it.”48

It’s a troubling assessment in a destructive war. Obama’s critics say fault lies in the absence of a coherent strategy. “The media is loud and noisy, but what was needed was a clearly articulated strategy, not a reactive one,” said Washington Post columnist David Ignatius.49 Obama’s supporters say his strategy resided in trying to avoid the risk of large-scale direct military intervention.

The wide array of foreign and Syrian actors all have their own assessment of what it would take to end Syria’s tragic war, and what lies behind the profound failures. Syria has paid a terrible price. It’s not the focus of this essay to explore these failures in detail. But this essay will next explore aspects of media coverage including social media with its risks of misinformation, misunderstanding, and manipulation.

Scholars have, over the years, broken down the concept of a CNN Effect in an effort to better understand the fluid relationship between media, public opinion, and government policy. In Piers Robinson’s Policy-Media Interaction Model, the impact of the media depends on three factors: whether there is a clear and firm policy for dealing with the crisis; if there is a consensus within the government; and the way the media frame the issue and if they take a side in the political debate. The first two have already been touched upon in this essay. The premise of the third is that, if a CNN Effect was to drive responses to humanitarian crises, the media had to frame it as a humanitarian issue. This key element was known by such phrases as “empathy framing.”50

But recent research shows that was not how the media framed the issue in the summer of 2013. A study by the Pew Research Center showed that cable TV networks, ranging along the political spectrum from Fox News to CNN and MSNBC to Al Jazeera America, all devoted “the biggest chunk of Syria coverage to the debate over whether the U.S. should become militarily involved in the conflict.” Stories with a humanitarian focus were highest on Al Jazeera America, but only amounted, in the Pew survey, to 6 percent of coverage. Other research confirms this finding.51

And when it came to taking sides, a detailed analysis by political scientist Walter Soderlund and colleagues of the range of commentary in three leading Western newspapers, including The New York Times, concluded that none of them “mounted a sustained campaign for any type of military intervention in the conflict but they all weighed the wisdom and feasibility of a variety of strategies to bring it to an end.”52 There was no consensus on what would work in what was seen as Syria’s deepening quagmire.

This Washington focus, and the uncertainty over responses to a humanitarian crisis, may have been magnified by the reality that, throughout most of the Syrian crisis, there haven’t been many, if any, American journalists on the ground. After early forays by Western and non-Western journalists into rebel strongholds, severe risks, including kidnappings and widely publicized executions by the Islamic State, kept them away. In Syrian government areas, visas were strictly controlled. American passport holders were largely banned for extended periods, including after the United States began targeted air strikes against IS forces. Other Western and non-Western media, including the BBC, do obtain visas. But most Western media were not allowed to stay for the kind of extended frontline reporting of earlier conflicts. “In Bosnia, we went there from the beginning and told the story of the war day in, day out,” recalled CNN’s Chief International Correspondent Christiane Amanpour, whose sustained coverage was widely watched. “It didn’t change policy, but it made the world know what was going on and we could always hold leaders’ feet to the fire with those pictures.”53

Only one Syrian battle was cited by several U.S. officials as a case in which TV cameras on the frontline made a difference: the Syrian Kurdish offensive in 2014 to seize the town of Kobani just inside the Turkish border from Islamic State. That fight was soon bolstered by U.S. air strikes. “We ended up acting in Kobani, not because it was more important than any other, but in part because it raised more questions than anonymous villages no one was watching,” said Philip Gordon.54 Correspondents from U.S. TV networks and other media set up their cameras on the Turkish side of the border to report, day in and day out, on fighting they could see “just behind” them. “The Kurds came to Washington and asked for more money and equipment and I think the reporting played a pretty key role in that,” said Anne Patterson.55 But, as with other examples of a CNN Effect, there were strategic reasons, too. Kobani coincided with the U.S. military’s search for local Syrian forces to fight the Islamic State. They already valued the role Kurdish fighters had played in Iraq.

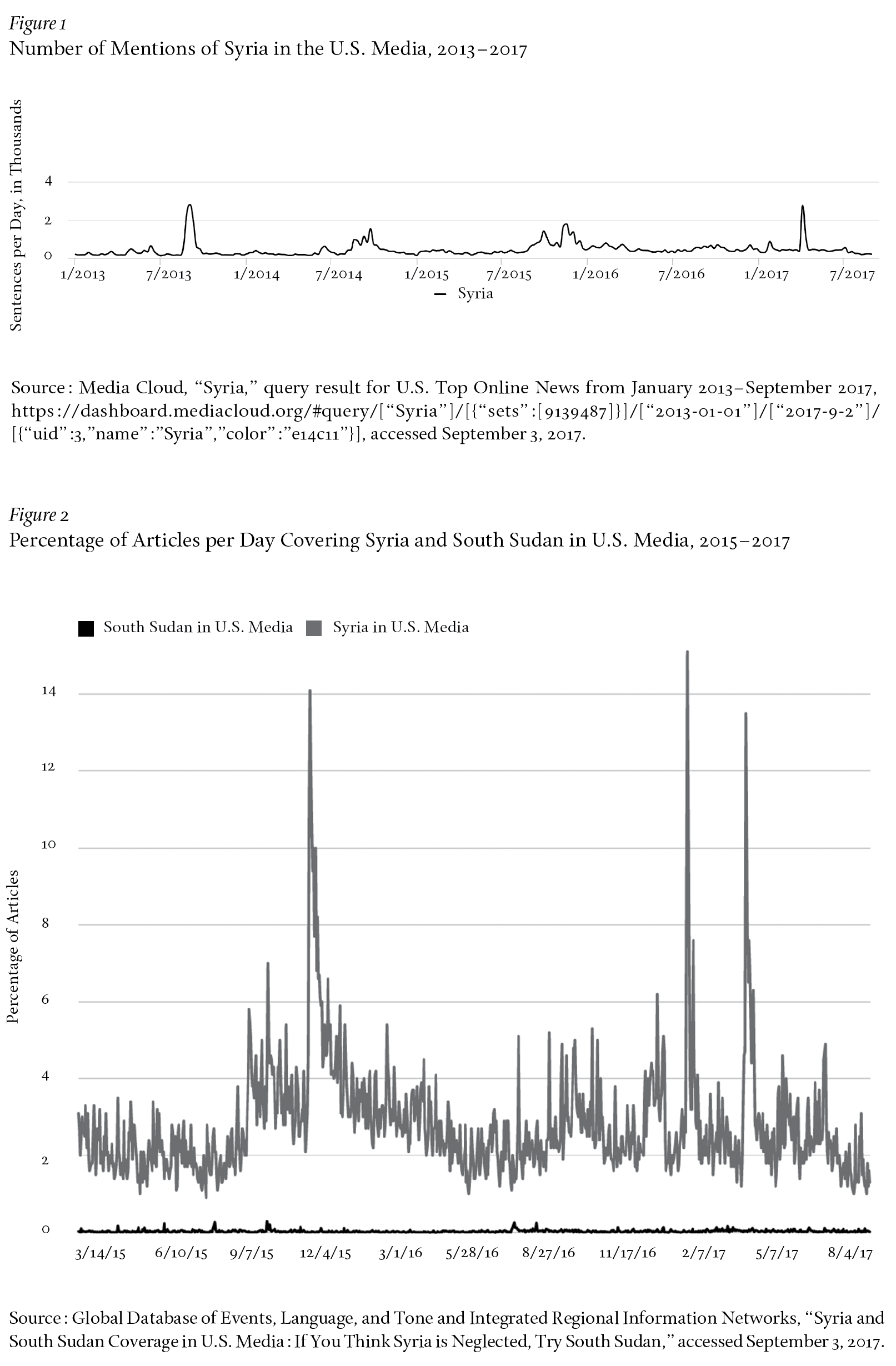

More frontline coverage may have made a difference. But journalists would still have had to compete for attention and space on an increasingly crowded news and information landscape. Data tracking U.S. news coverage of Syria highlight that spikes only occurred when there was a strong U.S. domestic angle, such as U.S. air strikes in April 2017 or the Trump administration’s travel ban in January 2017, which targeted Muslim-majority countries including Syria (See Figure 1). Unlike Afghanistan and Iraq, there was no major deployment of U.S. forces in Syria to amplify domestic interest although Special Forces have been on the ground since 2015 to assist Syrian rebel forces in the fight against the IS. It should be noted that other destructive conflicts received even less attention. Figure 2 tracks the very low incidence of reporting on South Sudan, a country described by a senior U.S. official as “a very dangerous place in which we’re seeing atrocities all the time.”56

The absence of sustained eyewitness and investigative reporting distorted coverage of Syria in a number of crucial and consequential ways. There has been some impressive reporting and informed commentary across a range of media including social media sites. But activists’ videos were often a main source of information from rebel strongholds. They often highlighted important issues including the horrific suffering in besieged areas. But they presented only part of a complex story. Media, including the BBC, spent considerable effort trying to check them. But they were often broadcast with a caution that they “could not be verified,” or came from activists.

And media watchdogs such as the Global Forum for Media Development have raised the concern that “parallel to the military conflict there has been an intense media war being waged by different sides in the conflict.”57 There’s been extensive reporting of the scope and scale of Russian state propaganda. On the other side, Western governments have provided significant funding to boost the profile of what was regarded as a “moderate armed opposition.” This was also widely regarded as a means of intelligence-gathering. A report in Britain’s Guardian newspaper, citing UK Ministry of Defence documents, detailed how contractors “effectively run a press office for opposition fighters” as part of “strategic communications.”58 Often, when I reported on the Western-backed Free Syrian Army, I would get a call from a British aide. Sometimes this exchange provided valuable clarification. Other times, it was to take issue with reports we were getting, from other sources, that moderate forces were losing ground on some frontlines to more hard-line Islamist fighters.

A ferocious battle was waged across a myriad of social media platforms over what is now labeled as “fake news.” The arresting photograph of five-year-old Omran Daqneesh, sitting alone and bloodied on an orange plastic chair in an ambulance, is just one illustration. The image went viral as a poignant symbol of the human tragedy caused by ferocious Russian and Syrian bombing of the northern city of Aleppo. Secretary Kerry took a copy of the image into his negotiations with Foreign Minister Lavrov. But Russian, Chinese, and Syrian state media dismissed it as part of a Western “propaganda war.” Critics accused the Syrian photographer of staging the scene. They also highlighted how he posed for a “selfie” with fighters from an armed group receiving U.S. funding, who beheaded a Syrian child earlier that year. That incident received relatively less attention in the Western press and led to accusations of double standards.59

Mainstream Western media, in the search for strong clear narratives in a chaotic war, often focused on the important story of Syria’s major human tragedy, including the heartrending plight of children. Less clear, and less reported, was an understanding of a shifting array of rebels ranging from more moderate to Al Qaeda-linked groups. Without regular access to government areas, there was also less focus on the situation there, including the views of Syrians still supporting President Assad. In contrast, Russian media and Syrian war reporters who report regularly from government frontlines highlighted an opposition they denounced as terrorists without a focus on the human cost of Russian and Syrian air strikes. Syria’s story required attention to all sides of an increasingly complicated battlefield.

The battle of videos confronted policy-makers, too. Rhodes recalls it in this way: “we’d get these reports on social media but it would take us time to verify which ones were true. And then the Russians and the regime would have alternative narratives and put up their own images and information and we’d end up in a debate over the facts.” Senior policy-makers, with access to the most advanced technology of our time, also struggled to make sense of a chaotic and complex war. Rhodes spoke of constant pressure in trying to “balance responses based on visceral emotion triggered by horrific scenes versus efforts to understand who was fighting whom, who is a proxy for whom, things you can’t learn just from those images.”60

This essay has sought to explore the role media played in policy responses to the Syrian conflict. I have focused on the United States as a key actor in this crisis. But similar observations would apply to other Western powers, including Britain. It is clear that media, in their many forms, are a major influence, but not a major power. Observations from the Trump and Obama administrations underline that the media were a key part of constant pressure on policy-makers from politicians, pundits, and the array of powerful actors involved in the Syrian crisis.

By the end of 2017, Syria’s crushing war had reached a major turning point. President Assad’s forces, backed by powerful allies and loyal supporters, had retaken large swathes of territory. Much of Syria now lies in ruin, its social fabric shredded. At the time of writing, Islamic State fighters are in retreat on the ground, but their brutal reach still threatens the region, and far beyond. Millions of Syrian refugees dispersed across the world fear they may never be able to go home. Few people had expected this conflict to cost so much and last so long. There are many reasons why. There are many to blame. But the failure to fully comprehend the dynamics of Syrian society, and to respond effectively, is a cautionary tale for journalists and policy-makers alike. It underlines again the pivotal role that journalism has to play in reporting and understanding the major crises of our time.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

With thanks to Professor James D. Fearon, Dr. Piers Robinson, Professor James Rodgers, Nik Gowing, Professor Rosemary Hollis, Professor Mary Kaldor, and Ambassador Karl Eikenberry for their comments on earlier drafts. Later drafts were read by Julien Barnes-Dacey and Damian Quinn. Thank you to journalists Kim Ghattas, Christiane Amanpour, David Ignatius, and Thomas Friedman for sharing their reflections on the role of the media. I am also grateful for the insights of Craig Oliver, former Director of Communications at 10 Downing Street, former UK Army Chief General David Richards, Baron Richards of Herstmonceux, and Brigadier Ben Barry.

Endnotes

- 1Andrea Mitchell, “Will the Image of the Syrian Boy Change Anything?” MSNBC Online, August 18, 2016.

- 2Philip Seib, The Al Jazeera Effect: How the New Global Media Are Shaping World Politics (Lincoln, Neb.: Potomac Books, 2008).

- 3Piers Robinson, The CNN Effect: The Myth of News, Foreign Policy and Intervention (London: Routledge 2002); and Walter C. Soderlund, E. Donald Briggs, Kai Hildebrandt, and Salam Sidahmed, Humanitarian Crises and Intervention: Reassessing the Impact of Mass Media (Sterling, Va.: Kumarian Press 2008), 281.

- 4Bahak Bahador, “Did Pictures in the News Media Just Change U.S. Policy in Syria?” The New York Times, April 6, 2017.

- 5E. Donald Briggs, Walter C. Soderlund, and Tom Pierre Najem, Syria, Press Framing, and the Responsibility to Protect (Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2017), 14.

- 6Daniel W. Drezner, Twitter post, April 7, 2017, 3:16 pm; and Daniel W. Drezner, Twitter post, April 7, 2017, 3:17 pm.

- 7Mark Landler, David E. Sandler, and Michael D. Shear, “Trump’s View of Syria and Assad Altered After ‘Unacceptable’ Chemical Attack,” The New York Times, April 5, 2017; and Spencer Akerman,”What’s Trump’s Plan for Syria? Five Different Policies in Two Weeks,” The Guardian, April 11, 2017.

- 8Author interviews, off the record, with a senior State Department official, Boston, November 2016; and author interview, off the record, with a White House official, October 2016. For Secretary Clinton’s views, see Wikileaks, “New Iran and Syria 2.doc,” Hillary Clinton Email Archive, November 30, 2015.

- 9Josh Dawsey, “Inside Trump’s Three Days of Debate on Syria,” Politico, April 7, 2017.

- 10Eric Trump quoted in Simon Johnson, “Ivanka Trump Influenced My Father to Launch Syria Strikes, Reveals Brother Eric,” The Telegraph, April 11, 2017.

- 11Jacqueline E. Sharkey, “When Pictures Drive Foreign Policy,” American Journalism Review (December 1993); and Robert Jervis, The Logic of Images in International Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989).

- 12Michael D. Shear and Michael R. Gordon, “63 Hours: From Chemical Attack to Trump’s Strike in Syria,” The New York Times, April 7, 2017.

- 13Author interviews with former and current U.S. State Department and White House officials, November 2017.

- 14“Syria Chemical ‘Attack’: What We Know,” BBC News, April 26, 2017; and author email exchange with Piers Robinson, September 2017. Robinson provided information on a working group of Western academics critical of Western policy, which refutes the evidence.

- 15Dawsey, “Inside Trump’s Three Days of Debate on Syria.”

- 16Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, “Does the ‘CNN Effect’ Exist? Military Intervention and the Media,” INA Global, July 3, 2012.

- 17Ibid.

- 18Babak Bahador, “Did Pictures in the News Media Just Change Policies on Syria?” The Washington Post, April 10, 2017.

- 19Nik Gowing, “Real Time Television Coverage of Armed Conflict and Diplomatic Crises: Does it Pressure or Distort Foreign Policy Decisions,” Working Paper (Cambridge, Mass.: The Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, Harvard University, 1994).

- 20Piers Robinson, “Media as a Driving Force in International Politics: The CNN Effect and Related Debates,” E-International Relations, September 17, 2013.

- 21Author email conversation with Mary Kaldor and Piers Robinson, September 2017.

- 22Richard Gowan and Stephen John Stedman, “The International Regime for Treating Civil War, 1988–2017,” Dædalus 147 (1) (Winter 2018).

- 23Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine,” The Atlantic, April 2016.

- 24Author interview with Rob Malley, November 2017.

- 25Author interview with Ben Rhodes, September 2017.

- 26“FULL TRANSCRIPT: President Obama’s Sept 10 Speech on Syria,” The Washington Post, September 10, 2013. Also quoted in Joshua Keating, “Is Obama a Victim of the CNN Effect?” Slate, September 10, 2013.

- 27Author telephone interview with Ben Rhodes, September 2017.

- 28David Remnick, “Obama Reckons with a Trump Presidency,” The New Yorker, November 28, 2016.

- 29President Barack Obama, Press Conference, Washington, D.C., November 14, 2016.

- 30Author interviews, off the record, with U.S. officials, Washington, D.C., October 2016.

- 31Author interview with Anne Patterson, Boston, November 2016.

- 32“Public Opinion Runs against Air Strikes,” Pew Research Center, September 3, 2013.

- 33Polls quoted in Eli Watkins, “Poll: Trump Approval Ticks Down, Partly Due to Drop among Base,” CNN Politics, May 15, 2017; and Dana Blanton, “Fox News Poll: Trump Approval Down, Voters Support Special Counsel on Russia,” FoxNews.com, May 24, 2017.

- 34Author interview with Rob Malley, Washington, D.C., October 2016.

- 35Doris Kearns Goodwin, “Barack Obama and Doris Kearns Goodwin: The Ultimate Exit Interview,” Vanity Fair, September 21, 2016.

- 36Author interview, off the record, with a senior U.S. military official, Muscat, Oman, October 2016.

- 37Author telephone interview, off the record, with a congressional aide, May 2017; and author interviews, off the record, with U.S. officials. It was beyond the scope of this essay to establish which actors are relying on which kind of media, but it is an important area of research for more empirical studies into the impact of media on policy-making.

- 38Author telephone interview with Philip Gordon, August 9, 2017.

- 39Author interview with John Kerry, Ditchley Park, United Kingdom, July 2017.

- 40Steven Livingston, “Clarifying the CNN Effect: An Examination of Media Effects According to Type of Military Intervention,” Research Paper R-18 (Cambridge, Mass.: The Joan Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Harvard University, June 1997).

- 41Author interview with John Kirby, Washington, D.C., October 2016.

- 42Author interview with Rob Malley, November 2017.

- 43Author interview with Anne Patterson.

- 44Ibid.

- 45Hillary Clinton quoted in Jeffrey Goldberg, “Hillary Clinton: Failure to Help Syrian Rebels Led to Rise of isis,” The Atlantic, August 10, 2014.

- 46Barack Obama quoted in Thomas Friedman, “Obama on the World,” The New York Times, August 8, 2014.

- 47Author interview with John Kerry.

- 48Author interviews, off the record, August–November 2017. See also Nikolaos Van Dam, Destroying the Nation: The Civil War in Syria (London: I. B. Taurus, 2017). In the early years of the war, the United States and other Western backers of the Syrian opposition repeatedly called on President Assad to step down even though they did not follow through with the kind of military intervention that could possibly have brought that about. It was also based on what many later realized was a misreading of the Syrian leader’s support inside Syria and external backing, as well as his determination to remain in power. In later years, U.S. officials focused on a “managed transition” to avoid the kind of state collapse crippling neighboring states. President Assad’s Russian and Iranian allies, who provided decisive military support, kept insisting his departure was a matter for Syrians alone and should be decided through elections. See Christopher Phillips, The Battle for Syria: International Rivalry in the New Middle East (New Haven, Conn., and London: Yale University Press, 2016).

- 49Author interview with David Ignatius, November 2017.

- 50Piers Robinson, “The Policy-Media Interaction Model: Measuring Media Power During Humanitarian Crisis,” Journal of Peace Research 37 (5) (2000).

- 51Pew Research Center, “How Al-Jazeera Covered America,” September 16, 2013. See also Hannah Werman, “Western Media Coverage of Syria: A Watershed for the CNN Effect?” Proceedings of The National Conference on Undergraduate Research, American University, Washington, D.C., April 2015.

- 52Briggs, Soderlund, and Najem, Syria, Press Framing, and the Responsibility to Protect.

- 53Author interview with Christiane Amanpour, London, May 2017.

- 54Author telephone interview with Philip Gordon, August 2017.

- 55Author interview with Anne Patterson.

- 56Carol Morello, “U.S. Warns South Sudan: Continued Chaos is Not Acceptable,” The Washington Post, September 2, 2017.

- 57Peter Carey, “The Pentagon, Propaganda and Independent Media,” Global Investigative Journalism Network, November 23, 2015.

- 58Ian Cobain, Alice Ross, Rob Evans, and Mona Mahmood, “How Britain Funds the Propaganda War Against isis in Syria,” The Guardian, May 3, 2017; and author interviews, off the record, September 2017. The contractors were reported to be InCoStrat, now renamed in2-Comms, which was founded by Paul Tilley, formerly the Director of Strategic Communications and Crisis Planning at the UK’s Ministry of Defence.

- 59Author email exchange with Piers Robinson, September 2017; and author interview with a Syrian human rights activist, Washington, D.C., September 2017. Examples of the different views on Omran Daqneesh include: Ann Barnard, “How Omran Daqneesh, 5, Became a Symbol of Syrian Suffering,” The New York Times, August 18, 2016; and Neil Connor, “Syria Crisis: China Claims Omran Images are ‘Fake’ and Being Used as Western Propaganda,” The Telegraph, August 23, 2016. On the earlier incident, see Martin Chulov, “Syrian Opposition Group that Killed Child was in U.S. Vetted Alliance,” The Guardian, July 20, 2016.

- 60Author interview with Ben Rhodes.