The Economics of Social Science Research & Knowledge Production in the Middle East & North Africa

Social science research on the Middle East and North Africa depends heavily on external funding. In this essay, we consider the implications of this reliance. In our review of calls for proposals and 924 grants and projects from 23 organizations, we find that this funding often centers the issues that Western policymakers view as salient but does not necessarily reflect the major concerns of those in the region; the funding recipients favor political science, leaving other disciplinary perspectives less developed; and the funding focuses heavily on select countries, while others remain understudied. Our investigation also uncovered a lack of coordination in funding that, combined with a fragmented research landscape, impedes knowledge accumulation. We conclude our findings with recommendations for steps that can be taken to overcome these problems.

External funding plays a particularly important role in shaping social science research and knowledge production on the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). In general, the MENA region suffers from one of the lowest global averages for research and development funding. The 2021 UNESCO Science Report revealed that the gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GRED) as a share of gross domestic production (GDP) for Arab states averaged 0.49 percent in 2018, compared with the global average of 1.79 percent.1

The problem is particularly acute for the social sciences, which are largely neglected in MENA countries.2 Many in the region view science and technology—not social sciences—as the key to fostering development, and elites in the region’s authoritarian regimes have little interest in promoting social sciences, especially those that challenge their basis of rule. Thus, according to the Arab Social Science Monitor (ASSM), in 2021, only 23 percent of 1,377 universities in the region offered economics, 17 percent offered political science, 15 percent offered psychology, 13 percent offered sociology, and less than 4 percent offered anthropology, demography, or gender studies.3 Social sciences ranked the second lowest among nationally funded research fields, averaging under 15 percent of GRED among Arab states.4

In this context, external funding for social science research is particularly influential. Reviews of research funding in the region consistently point to the heavy dependence on financial sources outside the region.5 As Ahmed Dallal, president of the American University in Cairo, points out, one should always remain mindful of the “potentially problematic relationship between the political sphere and the social sciences, whether such restrictive influence is driven by the self-serving agendas of the state or the political biases and interests of international funders.”6 Funders influence what researchers study, how they do so, and what purposes they serve. An analysis of the social science research that international agencies foster is thus key to determining the factors influencing knowledge production in and on the region.

It is far from easy to study the impact of research funding on knowledge production in the MENA. Funding for research comes from a wide range of sources, much of which is never advertised or published. To name but a few: international agencies, such as the World Bank and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), undertake research as part of their knowledge production, technical assistance, and monitoring efforts; foreign ministries and development organizations engage in ongoing assessments; nongovernmental organizations and think tanks pursue policy-oriented research; and the private sector employs researchers to conduct risk-analyses and other studies. These sources of support are important for all researchers, but especially those based in the MENA, where an estimated 80 percent of research is done outside universities.7 Both the funding and the findings of many of these studies remain unpublished or undisclosed. This creates challenges in knowledge accumulation and advancement, and makes it difficult to accurately assess the nature and impact of social science research funding.

Moreover, even gathering details of funding provided by major research foundations is often difficult. There are no central repositories of research calls or grants awarded by major research foundations for MENA-related social science funding, and publicly available information on such fundamental issues as the amount of funding, research topic and design, and principal investigators (PIs) is often incomplete. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that research is often carried out as part of cross-regional research projects, and it can be difficult to determine accurately the extent to which funding is earmarked for MENA-based research.

Some scholars use surveys to obtain information directly from researchers or funding organizations. Yet response rates are often low: about 50 percent of funders responded to an Africa Grantmakers’ Affinity Group (AGAG) survey, less than 13 percent of researchers participated in data specialist Jamal El-Ouahi’s study of MENA-based researchers, less than 8 percent of researchers responded to the ASSM’s 2019 survey of social science and humanities researchers, and less than 5 percent of the European funding agencies participated in a Horizon Europe–funded study, Connecting Research and Society.8 Key informant interviews or focus groups can help gain insights from a smaller number of individuals, but these may provide more information on how funders view their strategies than how these strategies translate into research support.9

Others use web-based information. One strategy has been to analyze funding acknowledgments of scientific articles indexed in the Web of Science to identify research funding. Unfortunately, with regard to the MENA region, such information is often absent or incomplete. El-Ouahi’s study of MENA-based papers found that more than half lacked funding acknowledgments, while a cross-national evaluation of social science funding by data scientists Xin Xu, Alice M. Tan, and Star X. Zhao found that Israel and Türkiye were the only two MENA-region countries with sufficient numbers of papers to be included in the study.10 The internet is particularly useful for identifying public calls for research, as in philosopher Anita Välikangas’s study of the place of the social sciences in interdisciplinary funding opportunities, although data on funded projects are often more difficult to obtain.11

Even with data in hand, there are inferential challenges to determining the impact of research funding on knowledge production. Funders influence scholars, in part because, as David Court, a former Ford Foundation representative in Nairobi, put it, “One has the resources; the other would like them.”12 Consequently, changes in funders’ priorities may lead scholars to shift their research focus. But donors are just one part of an ecosystem of actors and interests that shape social science research. Political forces and economic interests influence funders, researchers, other stakeholders, and the public at large. Thus, researchers may undertake social science research on issues arising from current events—such as the radical Islamic movements, the 2011 Arab uprisings, or civil wars—because they respond to funding priorities; but they may also do so because they are trying to make sense of the world around them or to respond to policymakers and other stakeholders who require answers to vexing local questions. In short, funders have influence, but they are not the only ones who do.

While we cannot determine exactly when and how funders’ choices shape social science research in and on the MENA, we can examine the relationships between funders’ choices, national interests, and published research. In doing so, we interrogate the widespread belief that national interests shape funding priorities—and we find that they do. We can also reflect on the negative impacts this has on knowledge production, given the MENA region’s high dependence on externally funded social science research, and consider potential solutions.

The insights presented here draw on a sample of funding calls and awards available on the internet. Researchers at the Governance and Local Development Institute compiled a list of funding sources originating from Europe, the MENA, and the United States.13 The initial search found forty-four funding sources of various types. A review of the availability of information these sources provided to answer the questions at hand resulted in twenty-three remaining organizations. These fit into two categories: external organizations that conduct or fund research on MENA countries, and MENA-based organizations.14 The latter can be further divided into centers in and of the region, and centers located in the region but funded by foreign entities.

Researchers gathered two types of information from these sources. The first dataset focuses on 924 grants and projects funded by these organizations.15 The second includes calls for proposals, which allows us to consider the extent to which donors explicitly attempt to shape research agendas and processes. Unfortunately, calls for proposals were not available from all donors examined in this report. Thus, we focus on a select group of funders, including the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Carnegie), Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (RJ), the Swedish Research Council (VR), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), and the European Union Horizon Grants.

Eight research associates coded the material gathered on the awarded projects and calls. Most information was available on the organizations’ websites; however, the team used Google searches to find additional information when necessary. Most often, this was information about the specific project, PIs, and collaborators. All links were saved to ensure the coding process could be replicated by a third party. Funding values in different currencies were converted to an equivalent U.S. dollar (USD) amount using a yearly average cross-currency rate provided by Sveriges Riksbank.16

Our data collection process encountered some challenges. It was often not possible to acquire complete and accurate information for grants. There were cases of missing details regarding certain aspects of funded projects during the review period. Missing data problems were particularly acute for projects funded in the more distant past. The goal was to examine funding trends from 2001–2021. However, some funding organizations do not have records of previous projects readily available on their websites, and other funding organizations that used to support social science research in MENA countries have been discontinued. To address these issues, we focus our primary analysis on the more recent time frame, 2016–2021, for which there was a higher level of completeness and comparability among funding sources.

Resource constraints and limited availability of information result in a dataset focused primarily on funding of research projects from select foundations in the United States and European Union.17 As we discuss in the conclusion, this leaves important questions about the extent to which these funding streams are congruent with or differ from funding from private sources, multilateral organizations, MENA-based public foundations, and others that foster the production of social science knowledge. We are also unable to assess the nature and impact of funding from other regions of the world, including East Asia, which are increasingly engaged in MENA countries.18 Given this, the analyses shed light on how funding from the West shapes social science research in the region.

National priorities appear to shape funding decisions. Some grants cover multiple topics or countries, and in some cases, the topic or country of focus is not specified in the available data. Thus, findings provide general trends and insights, not iron-clad facts. Typically, however, they suggest that current global challenges shape donor priorities, which in turn influence social science research.

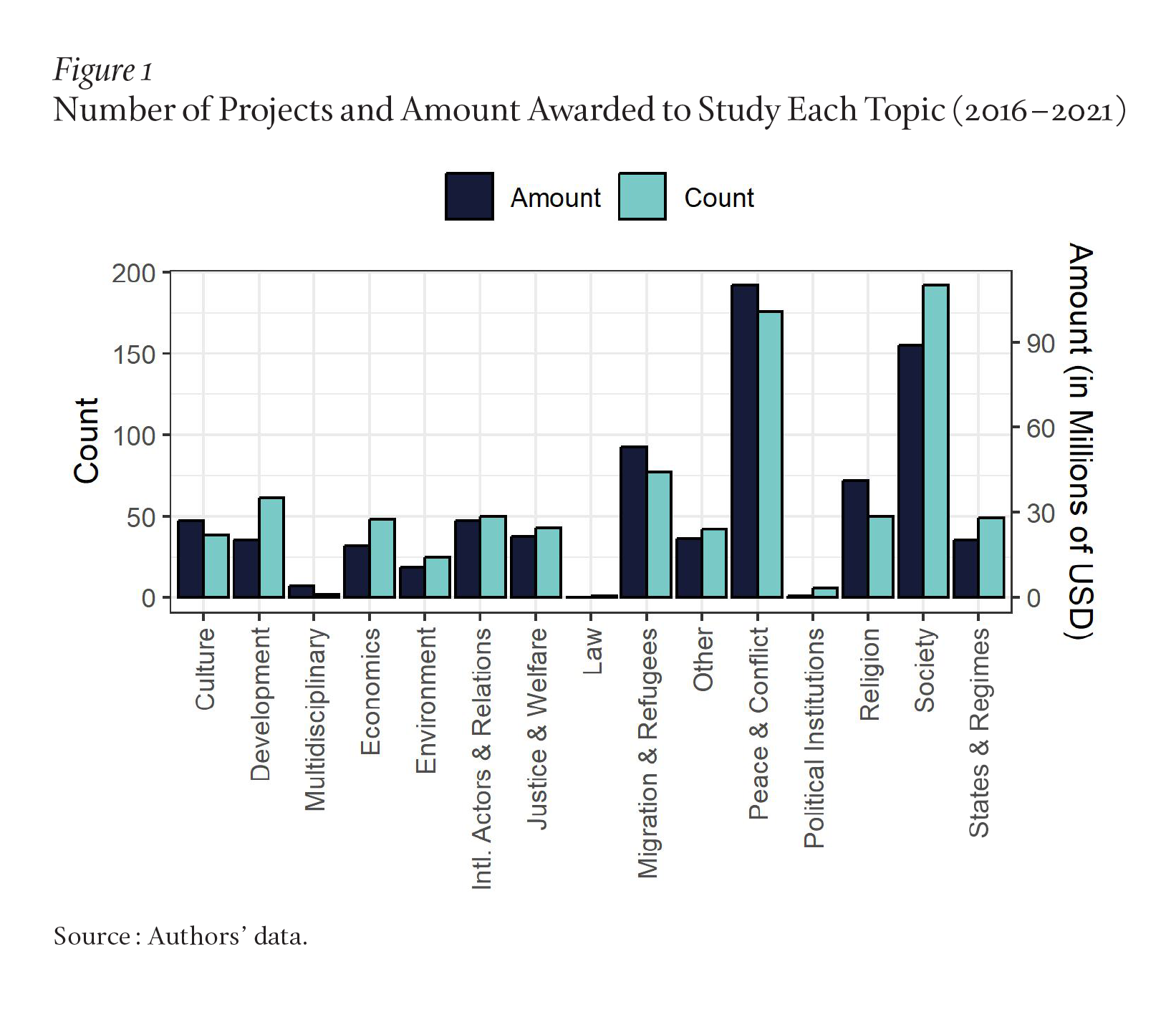

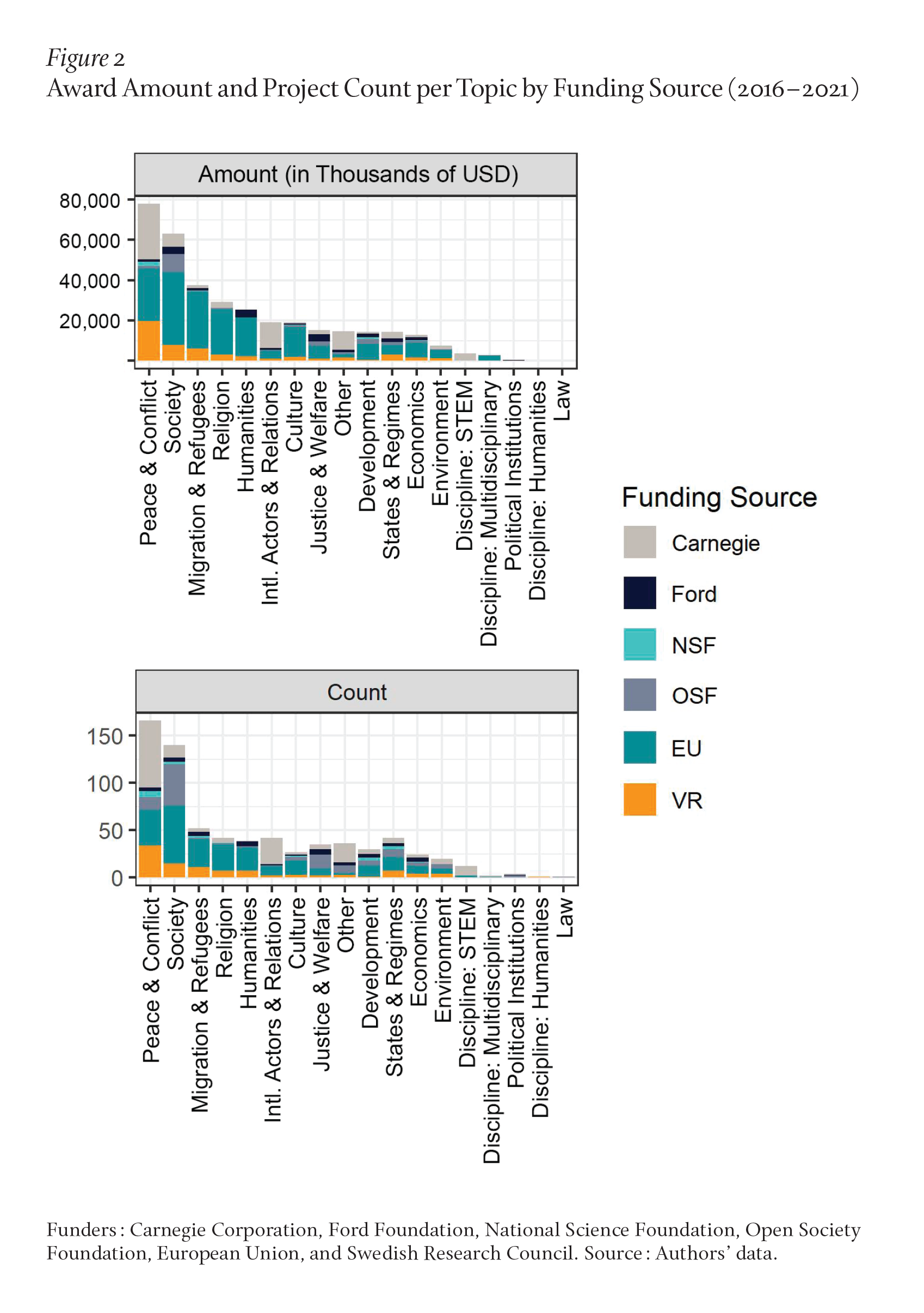

In general, most of the research funding in the recent past has been directed toward topics related to peace and conflict, society, and—to a lesser extent—migration and refugees.19 As seen in Figure 1, these topics are well-represented, both in terms of the number of projects and dollar value of grants awarded. In contrast, there were fewer projects and less funding directed toward studies related to law, the environment, and political institutions. But there are important differences in the issues that funders prioritize.20 U.S.-based foundations appear to devote a sizeable amount of their financing to research on peace and conflict, international relations, and, to some extent, society. European foundations also support research on peace and conflict and society (see Figure 2); however, they also pay greater attention to religion and migration and refugees.

This is not surprising. Migration is a more immediate concern to European countries than it is to the United States, in part given the increase in migration following the Arab uprisings, economic crises, and onset of civil wars. The European Union received 632,430 applications for asylum in 2022, accepting 310,470.21 Sweden alone saw nearly 17,000 asylum seekers; Germany over 175,000; and France over 62,000.22 Not all came from the MENA, but significant numbers did. This stood in stark contrast to the United States, which admitted only 25,519 refugees in 2022, of which 7,075 came from the Near East/South Asia and 11,393 from Africa.23 The European emphasis on research regarding migration reflects social and political challenges of the donor countries.24

Likewise, there is reason to believe that U.S. donors’ focus on international relations, compared with European donors, reflects greater involvement of the United States in international relations and defense. The European Defense Agency reports that the twenty-seven member countries in the European Union spent EUR 240 billion (approximately USD 260 billion) on defense, compared with the United States’ defense expenditures of EUR 794 billion (approximately USD 857 billion) in 2022.25 The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s (SIPRI) estimates are even higher, reporting that the United States spent USD 877 billion on defense in that year, compared with Europe’s USD 477 billion.26 European countries’ average defense spending is approximately 1.5 percent of GDP, versus an estimate of 3.5 percent for the United States.27

The United States is not only more invested than Europe in international security and defense, but it is also more heavily involved in military operations in the Middle East. Many European countries have recently increased their defense spending, but this is primarily due to concerns over Russia.28 The United States, in contrast, has embedded investments in MENA countries, including military assets and personnel in permanent or host-government–operated bases to protect national interests such as oil or the outstanding commitment to Israel. It is thus not surprising that U.S. donors spend more to fund research on international security in the region.

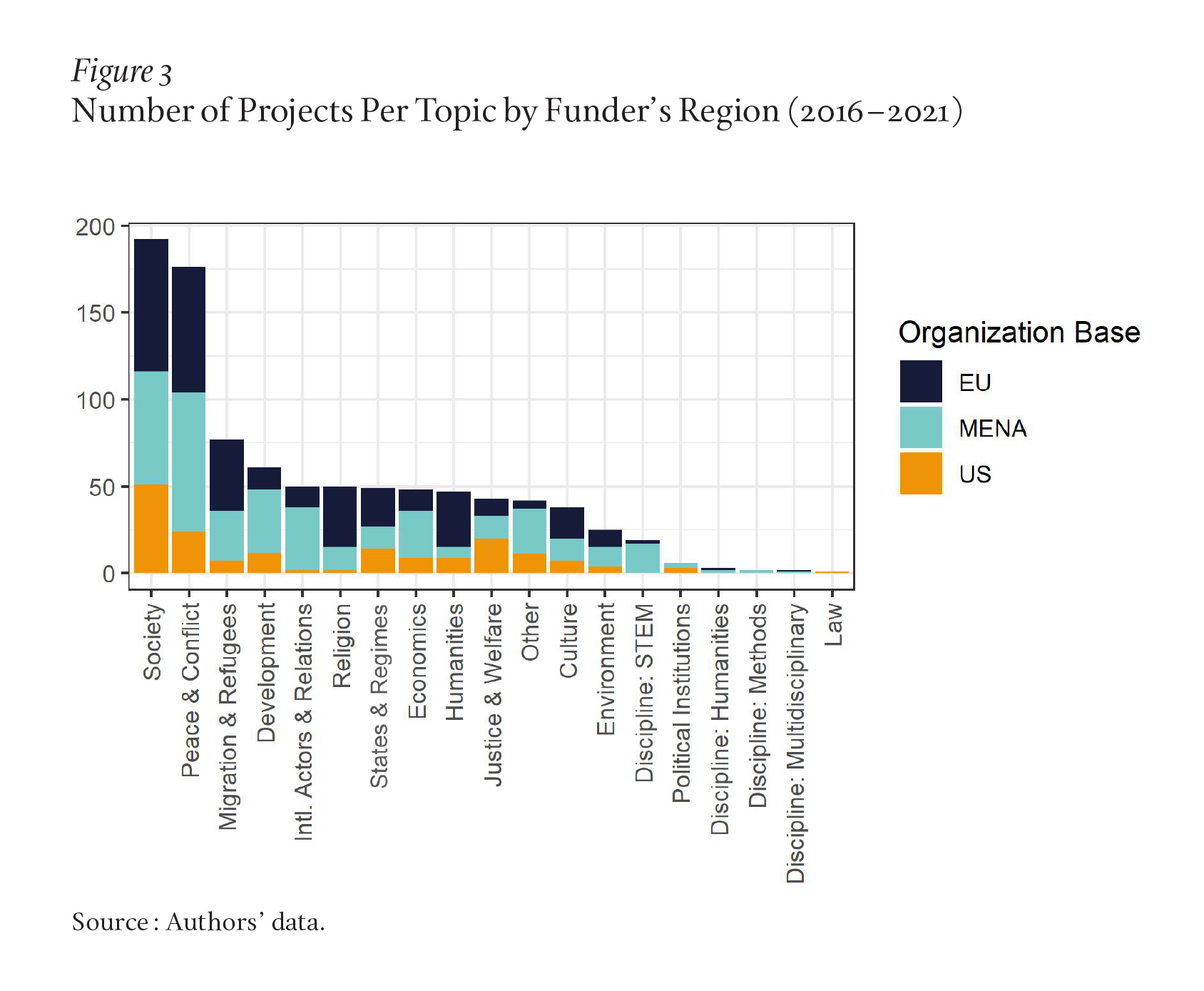

There also appear to be some important differences between the priorities of U.S. and European funders and those in the region. As noted above, social science research funding in the MENA is limited, and there are also difficulties in obtaining information on funding schemes that exist. However, in Figure 3, we compare European and U.S. funding with that from organizations based in the MENA region for which we have available information. We see that the number of projects focused on peace and conflict and society funded by MENA-based organizations are similar to those funded by their U.S. counterparts. However, MENA-based organizations tend to invest more in research on areas such as development, economics, and the environment than higher-income country (HIC) funders.29 These more “local” issues are particularly significant to individuals located in the region. At least at present, however, they are not seen as impacting the peace, stability, and welfare of policymakers and other key stakeholders in the West.

National priorities also appear to influence which countries within the region receive attention. Estimating the amount of funding supporting social science research in each country is not straightforward. Many projects are multicountry efforts, and available data often fail to provide country-level allocations. In addition, variations in the size of countries, levels of economic development, or the existence of conflict mean research in some countries is simply more costly than in others. Higher funding levels do not necessarily mean that more researchers are funded, days of fieldwork supported, or surveys implemented. However, it may signal funders’ priorities.

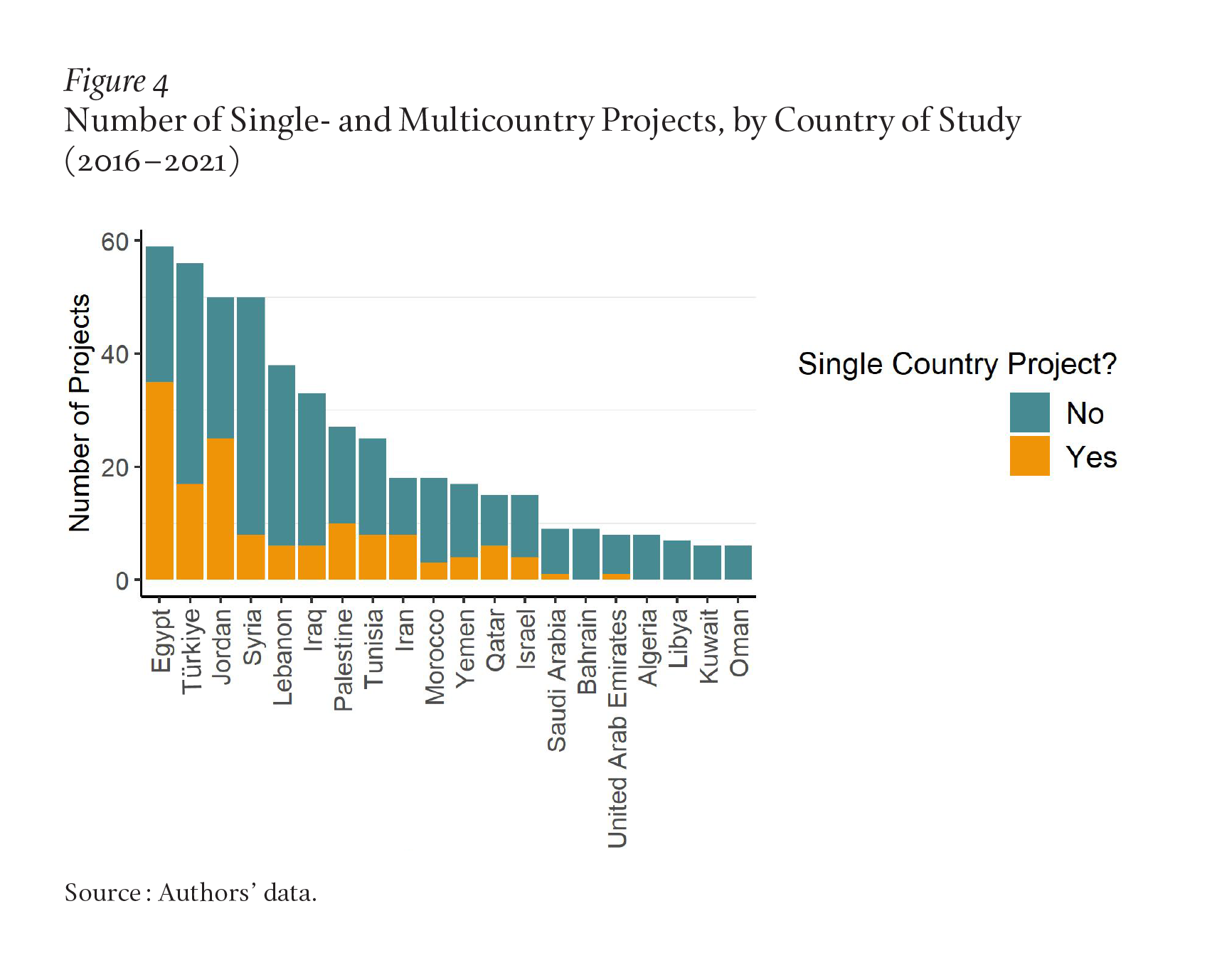

We first consider the number of projects funded and whether the country was the sole focus of the study or part of a multicountry comparative study. In Figure 4, we see that funding organizations support more projects on Egypt overall, and that projects on Syria are also highly likely to be funded. However, while funders often support single-country projects on Egypt, they have done so much less frequently in Syria.30 Many other countries—such as Türkiye, Palestine, Lebanon, Iran, Tunisia, Morocco, Iraq, Qatar, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen—were also more likely to be part of multicountry projects. Jordanian research projects appear to have had equal access to funding for both single and multicountry projects.

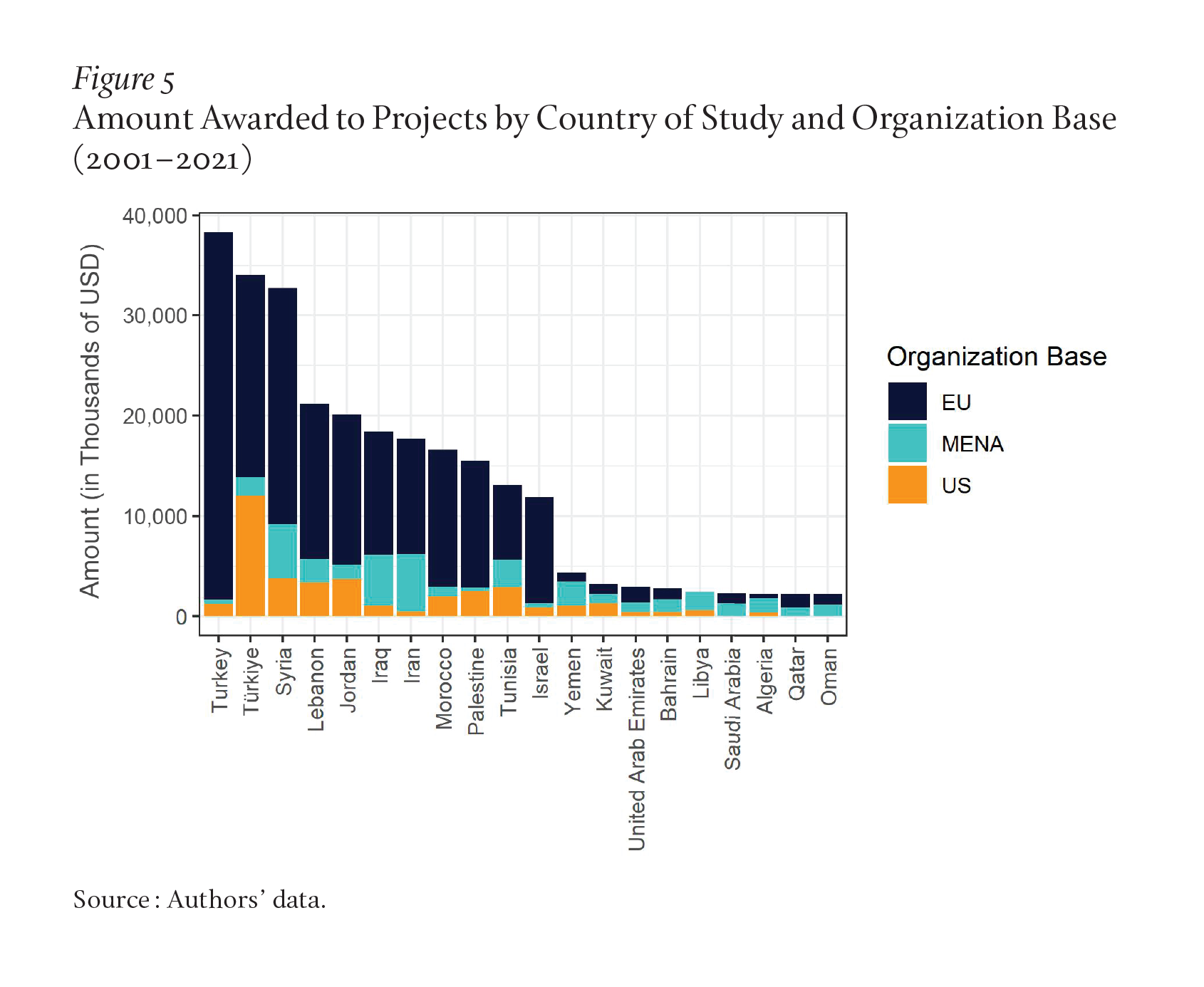

In exploring how much money is awarded for research in each country, we consider whether projects are funded as single- or multicountry initiatives. Egypt received the most funding at over USD 20 million.31 Türkiye and Syria also received substantial funding. Additionally, Palestine, Iraq, Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan, and Israel each received similar amounts—around USD 5 million. The estimated awarded amount per country was determined by dividing the total awarded amount by the number of countries studied in the project. This is an estimate, as projects may not allocate funding equally in each country. However, in the absence of more complete data, we believe it provides a useful measure.

The available data indicate that European and U.S. domestic interests affect which countries receive attention (see Figure 5).32 For example, the European Union tends to fund more research on Türkiye, which sits at its doorstep, has long sought accession to the European Union, and serves as a key transit hub for irregular immigration into Europe. The United States has invested more in research on Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, which neighbor Israel, the United States’ long-standing ally, and which the United States views as key actors in any lasting peace agreement.33

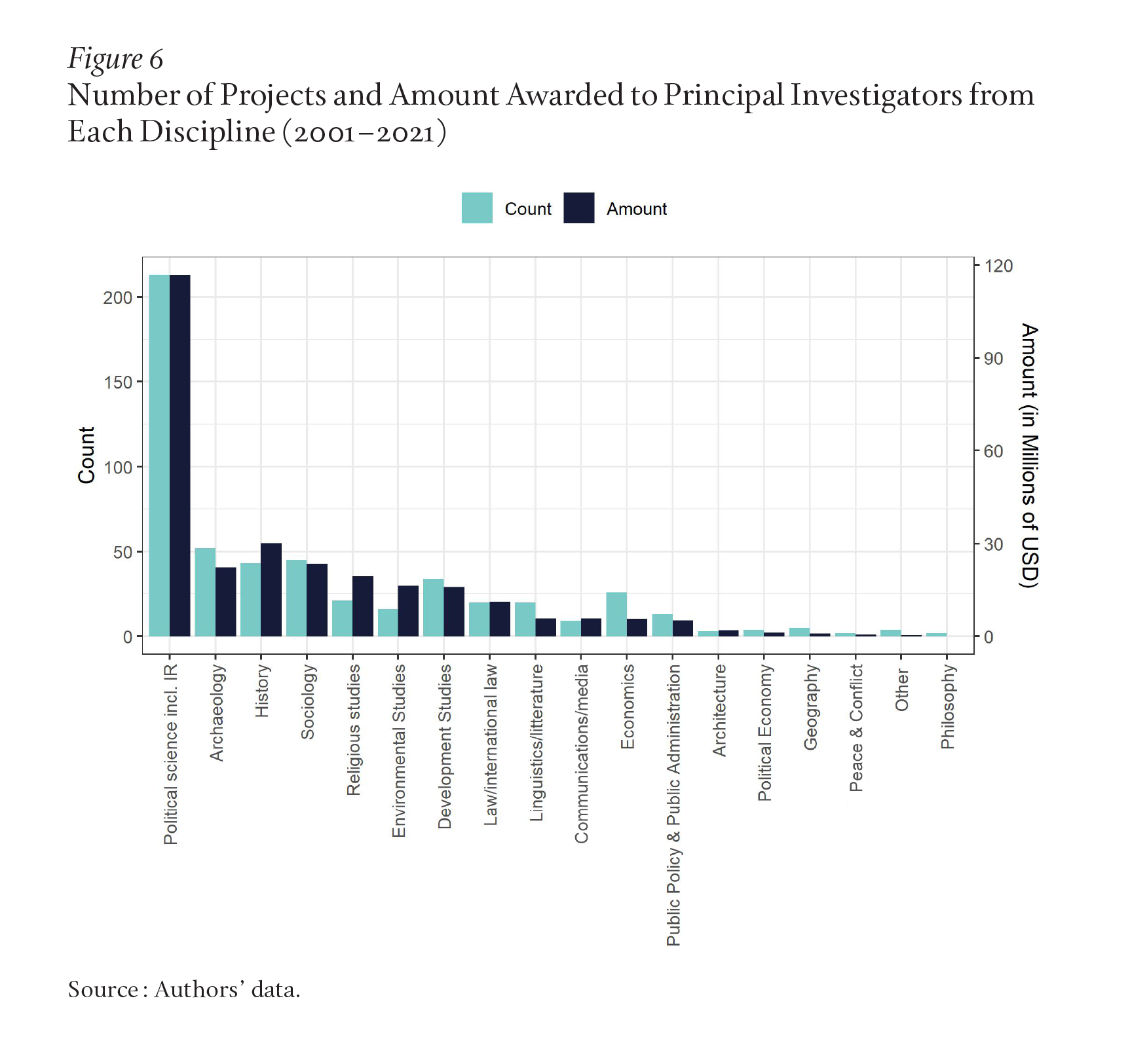

Perhaps unsurprisingly, European and U.S. funders appear to prioritize funding social science disciplines and research teams most closely related to key strategic interests. The majority of identified principal investigators work in fields related to political science, as shown in Figure 6. More projects are led by a single PI than by teams, and when there are teams, they either entail partners in the West or collaborations between Western researchers and individuals in MENA. Funders are not particularly focused on promoting collaboration among scholars in the region.

Calls for proposals reflect this as well. While some donors require collaborations, either across non-MENA countries or between MENA and non-MENA countries, we did not find calls that specifically required collaboration across the MENA region.34 We also find that most calls (over 70 percent) do not specify research topics or fund those in specific disciplines. But even when funders issue “open calls,” the trendiness of topics and both the donors and reviewers’ perspective of “relevance” likely steer the research direction toward national interests in the donor’s country.

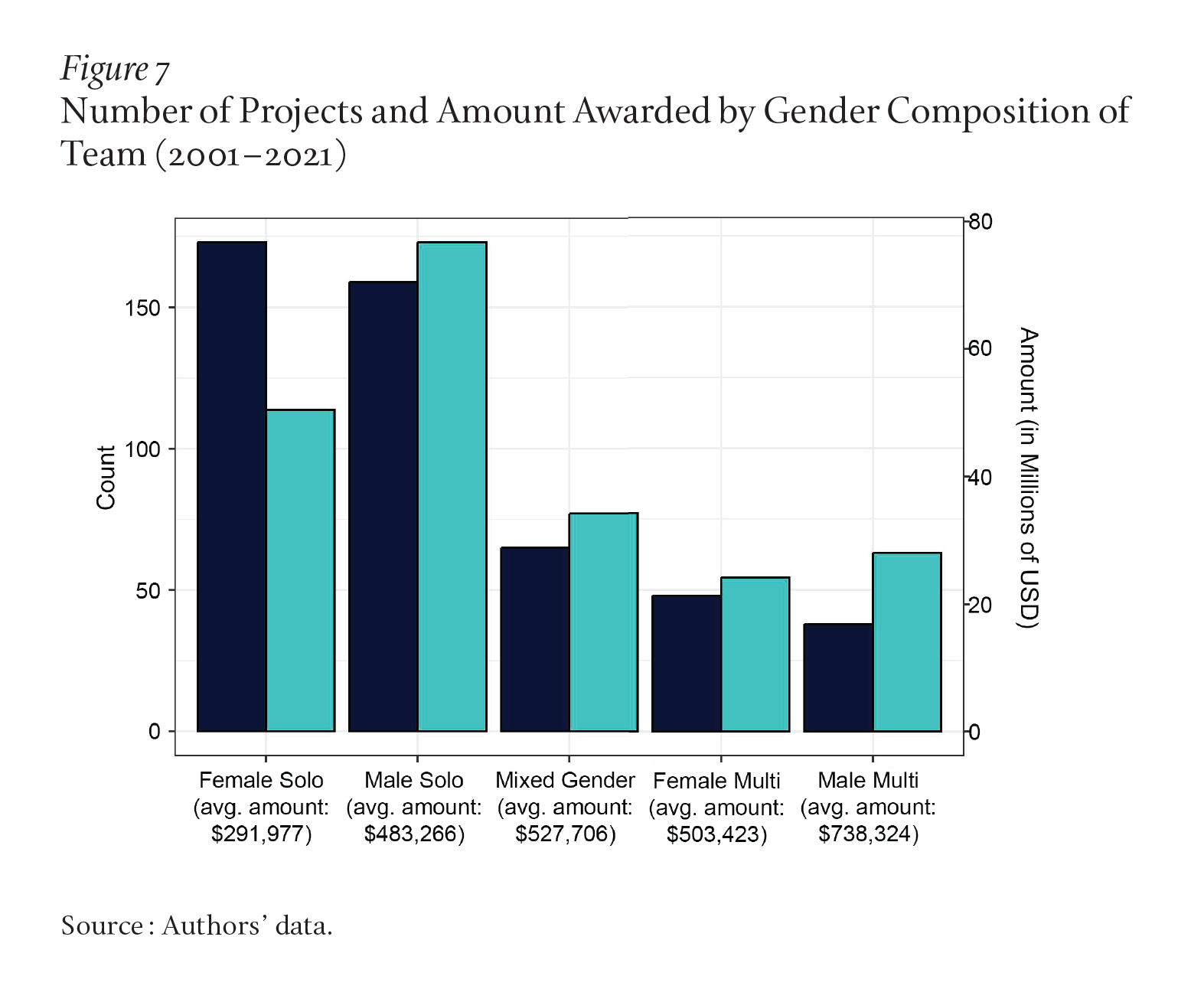

Finally, it is worth noting that we find gender differences in the funding PIs receive. Funders supported more female-led projects (solo female or all-female teams) than male-led projects. Yet, on average, they gave less funding to female PIs than to male PIs or mixed-gender teams. Solo male PIs received approximately 65 percent more funding per project than solo female PIs, and all-male PI teams received over 45 percent more funding per project than all-female PI teams. This may be because male-led and mixed-gender teams are more likely to lead larger projects, employ more expensive methods, request greater amounts of funding, or receive their full-budget requests (Figure 7).35 Thus, while some funders seek to disrupt gender hierarchies in MENA countries, it is not clear if these same gender considerations shape funding decisions.

Social science scholarship reflects funding patterns at least partly because funders shape research. Studies on MENA political science scholarship—the discipline receiving the most funding—find that publications align with funding patterns from the United States and, to a lesser extent, Europe. Examining articles published between 2000 and 2019 in leading political science journals, political scientists Melani Cammett and Isabel Kendall find scholars concentrated on social mobilization, conflict, and international relations; regimes, political institutions, and elections; and religion and politics, while giving less attention to such areas as political economy and development or gender.36 Similarly, political scientists Mark Stephen Berlin and Anum Pasha Syed’s analysis of articles published in nine highly ranked journals concludes that regimes, political violence and international conflict, and religion and politics receive the most attention.37 In contrast, issues such as development and the environment, which align with funding priorities in the region as revealed by available data on MENA funding, receive little attention.38

We see a similar relationship between funding patterns and the countries of studies published in these journals. Berlin and Syed find that research is most frequently on Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Palestine, and Türkiye, while countries in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula receive little attention.39 Moreover, they uncover a relationship between issue areas and countries that is in line with the national interests of external funders (and institutional homes of most of these researchers).40 For instance, the regional Palestine-Israel conflict receives far more attention than regional disputes in North Africa, Iran, or Saudi Arabia and Yemen—a fact that is better explained by Western strategic interests than the duration or importance of these conflicts.

Authorship of publications in the top political science journals also aligns with funding patterns. U.S.-based scholars wrote nearly 72 percent of the single-authored articles coded in Berlin and Syed’s study, compared with 15 percent composed by MENA-based scholars. Moreover, most MENA-based authors were from Israel (79.5 percent) or Türkiye (11.4 percent). Only 3 of the 283 articles in Berlin and Syed’s dataset were solo-authored articles by scholars based in a majority-Arab country. Similarly, the majority (59 percent) of coauthored articles, which became more frequent after 2011, were collaborations between scholars based in the United States. Only 19.8 percent resulted from collaborations between scholars in the United States and MENA, 2.5 percent between scholars in Europe and MENA, and 2.5 percent from scholars in three regions, including MENA countries.41

The apparent bias toward Western interests and authors is particularly important for MENA social science knowledge because the dissemination and integration of MENA-based scholarship in the West is limited. As sociologist Mohammed Bamyeh noted in the 2015 ASSM report, social science journals in the Arab world are nascent and, in contrast to the leading Western journals, are issued by independent research centers (52 percent) or universities (37 percent), rather than scholarly associations (less than 6 percent).42 Moreover, most scholars publishing in the top-ranked Western journals fail to cite local-language sources, let alone engage critically with scholarship from the region.43

This leaves a chasm between social science scholarship in the West and realities of MENA cultures that hinders all sides. Scholarship funded by, and often produced and published in, the United States and Europe focuses on the region as it fits into U.S. and European interests, advancing theories based on paradigms founded in Western experience. Entire countries—and many areas of countries that do receive attention—are overlooked. More important, social science concerns in the region, which prompt scholars to ask different questions and may productively foster new paradigms, are left un(der)studied and unpublished.44

High dependency on externally funded social science research on the MENA hinders policymakers and other key stakeholders. A focus on established policy concerns and limited ability to learn from MENA-based scholars leads to an incomplete and even misleading understanding of the region.

Newly emerging issues that may reshape power relations, spark discontent, and ultimately spill over to global affairs are easily overlooked. The 2011 Arab uprisings serve as one example. Focusing on national-level political institutions and engagement obscured the mismatch between macro-level economic development and local-level realities. This led not only to a failure to address inequalities, but ultimately to an inability to anticipate how they would become a catalyst for the uprisings, with subsequent implications for war and migration. A short-sighted emphasis on strategic issues and policy concerns—as viewed by the West—leads to an inability to recognize challenges and proactively develop robust solutions.

Focusing on a small subset of countries poses similar problems. The strategy may allow scholars, policymakers, and other stakeholders to develop a better understanding of the countries of study, although this understanding is often seen through the lens of specific issues, research in capital cities, and perspectives of well-known interlocutors. Such focus also leads to far less understanding of other countries. This promotes, and is exacerbated by, a tendency to generalize about the MENA region based on the findings from selected countries and sites. This undermines the West’s ability to fully understand the region, given the enormous diversity both across and within countries.

What can be done? It is neither surprising nor necessarily bad that funders in the United States and Europe aim to channel resources into social science research that addresses strategic national issues. Funding often comes from taxpayers’ support, and these issues are of concern to citizens, policymakers, and researchers alike. The difficulties arise due to the imbalance in the strength of MENA-oriented funding and social science communities in the United States and Europe compared with those in the MENA region, and the lack of communication between them. Given these inequalities, current social science funding and research overlook important issues, countries, disciplines, and perspectives, to the detriment of publics in the West as well as the MENA region. Addressing these inequalities is in the interest of all.

One step is to diversify funding for MENA social science research. U.S. and European funding can continue to play an important role, supporting scholars both in and outside the region. As Paul Tiyambe Zeleza, a U.S.-based Malawian historian, noted in a keynote address at a conference on historical and social science research in his home country, where governments seek to “manage universities in the same way they [manage] roads, the army, or customs,” external funding can be an important source of support to scholars based in the region.45 It can shield researchers from political pressures and provide necessary resources in underfunded fields.

But external funders engaging in the MENA need to guard against three challenges. First, external funding, particularly from sources in the United States, can also be a political liability to MENA-based researchers, making even the best-intentioned support counterproductive. Second, the tendency to favor—or to be seen as favoring—work on certain issues, approaches, or paradigms remains a problem. Social science donors and research communities in both the West and the MENA will be better off when issues of concern to those in the region are placed on the table and research approaches and paradigms are diversified. Thus, external donors need to signal their openness to new issues and approaches, ensuring that MENA-based scholars can prioritize their interests over those they view as U.S. and European priorities. Third, external donors need to extend their networks and support beyond their comfort zone. Understandably, foundations tend to support MENA-based researchers who have been educated in U.S. and European institutions, can easily converse in Western languages, and fit comfortably within U.S. and European networks and paradigms. These scholars deserve support, but to reap the benefits of diversity, external donors need to pay additional attention to other MENA-based scholars, whose approaches and interests may more fundamentally challenge Western assumptions.

MENA-based support is important as well. Foreign funding can help shield social science researchers from local constraints, but domestic funding can provide an important buffer from external interests. As Dallal explains, social science and humanities (SSH) research “is increasingly dependent on foreign funding and is locally marginalized due to lack of state support. In this sense, rather than undermining intellectual autonomy, state support protects the independence of SSH research from overreliance on the agendas of international organizations.”46 Not all domestic funding needs to come from state coffers. Particularly in a region that boasts a highly educated, successful, and well-endowed segment of the population, universities and institutes have opportunities to garner social science research support from private donors.

A related step in addressing the problems raised in our study is to increase the prestige of social science research within the region. Researchers in the MENA often face problems of low salaries, insufficient support, and little reward for research, and consequently, they invest their time in more lucrative activities, such as consulting or maneuvering for political positions. Reversing this requires strengthening professional communities and changing incentive structures. There have already been some important initiatives in this regard. With external funding, the Arab Council for Social Sciences, Arab Political Science Network, and other comparable initiatives are examining the landscape of social science in the region and taking steps to strengthen it. New universities and institutes, such as the Doha Institute in Qatar, are being established, supporting and rewarding research activities in an attempt to build an Arab social science. Such efforts not only provide support for MENA social science research but also foster collaboration and competition that can strengthen social science research across the region.

A third step is to strengthen coordination and communication. Our study uncovered three gaps that hinder the development of MENA social science research. First is the lack of coordination and communication between research funders. The lack of comprehensive information on research funding not only makes it difficult to assess its impact, but it also makes it difficult for funders to coordinate. Coordination may ultimately allow funders to better diversify funding, supporting issues and areas that are currently understudied. Second is the lack of coordination and communication between researchers within and outside the region, as evidenced by the dearth of coauthorships and cited research in U.S. and Europe-based publications. One way to address this problem is by requiring collaboration across regions, but this approach sets up rent-seeking dynamics that ultimately undermine collaboration on equal footing. A potentially more productive way to address this is by supporting the publication and dissemination of cross-regional, peer-reviewed journals, thereby raising their visibility and influence. Finally, there is a need to coordinate and communicate the results of the large amount of social science research produced outside the halls of academe in the region. Strengthening MENA-based journals and incentivizing scholars to engage in social science research may prompt them to publish more of these findings.

Taken together, these steps may help foster a broader range of social science research on the MENA. This will advance social science theory and area studies knowledge by incorporating a larger community of scholars and supporting research on a wider range of topics, in a broader set of contexts, using more diverse approaches. In doing so, it provides a more holistic understanding of the region, helping scholars, policymakers, and citizens make better choices in an increasingly fragile world.

authors’ note

This essay draws on the report The Economics of Social Science in the Middle East and North Africa: Analysis of Funding for Social Science Research and Knowledge Production in the MENA Region, prepared by the Governance and Local Development Institute, Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg, 2024. See also the accompanying Supplementary Information to The Economics of Social Science in the Middle East and North Africa. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of the many GLD team members who contributed to the underlying report: Hanna Andersson, Jennifer Bergman, Sara Bjurnevall, Mina Ghassaban Kjellén, Emelie Hultén, Paulina Jennebratt, Erica Ann Metheney, Linnéa Nirbrant, Kristin Bäck Persson, Victor Saidi, Rose Shaber-Twedt, and Joel Sigrell. We also benefited from input from Nehal Amer, Lisa Anderson, Rabab El-Mahdi, Dima Toukan, and other members of the REMENA project. The Swedish Research Council International Recruitment Grant (Swedish Research Council–E0003801) funded the report.