Integrating Social Science Research across Languages with Assistance from Artificial Intelligence

Disseminating new research findings and integrating them into future research are crucial tasks for cumulative knowledge production. We address the challenges of dissemination and integration of research in the social sciences of the Middle East and North Africa region, where scholarship written in Arabic is often overlooked by scholars writing in English. Although this marginalization reflects differences in taste, quality, method, and theory, some of the hierarchy is due to English-language scholars’ lack of awareness of relevant Arabic-language work. This ignorance is perpetuated by inaccessibility. We propose an open-source translation tool to aggregate relevant articles based on artificial intelligence models to lower the cost of cross-language literature review. If English-language researchers are willing to commit to the ethical value of integrating work published in local languages, recent technological developments make it feasible.

“Is there relevant research in local languages that you should consider citing?”

If journal editors, mentors, and reviewers ask this question more often, it could encourage scholars to incorporate relevant new knowledge no matter the language of publication. But even scholars with intentions to cite research in local languages struggle to do so because tools for integrating knowledge across languages are inadequate. We show how machine learning models—the subset of artificial intelligence (AI) that trains algorithms to perform certain tasks—can make cross-language research discovery easier. Our focus is social science scholarship about the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, but our approach could apply to any field in which relevant knowledge is published in different languages.

Integrating new knowledge is a core task of research. Integration happens primarily through literature search and review of publications by other scholars, acknowledged via citation. In the social sciences of MENA, research published in Arabic is rarely cited by English-language researchers.1 There are many reasons, but inaccessibility of Arabic-language research plays a key role. Scholarly communities and the reviewer pools in English and Arabic are largely separate, so reviewers of English-language articles will rarely point out missing citations in Arabic. Tools like Google Scholar have transformed how scholars access and integrate new research in English, but these tools don’t currently facilitate cross-language research discovery. And the absence of cross-language citations is self-perpetuating because scholars often look to past scholarship to learn what they should be citing.2 All told, there are few consequences for English-speaking scholars who do not incorporate Arabic-language scholarship into their works, and high barriers to doing so.

This language-based hierarchy of the social sciences should change. Authors can reasonably decline to cite relevant research for many reasons, but “I didn’t know about it because it was in the local language” is a weak rationale. Successful integration of scholarship across languages is more likely with: 1) normative commitments that encourage cross-language citation and 2) technological changes—enabled by AI—that make it feasible for scholars to meet these normative commitments. But doing so without adequate tools is difficult. Reflecting on a personal experience of egregiously missing a citation, described more below, we argue that existing tools for integration are not adequate for cross-language searches in the MENA social sciences. Shaming English-language researchers into including more Arabic-language citations may increase perfunctory citations. But we hope that helping scholars feel the intellectual excitement of discovering new research by improving cross-language accessibility and reducing search friction will bring about deeper integration.

We propose a tool to help integrate scholarship across languages that eases the difficulty of searching for research on similar topics in unfamiliar languages. Our solution uses machine translation and a statistical topic model to identify research in Arabic and English on comparable subjects. Our prototype can recommend matches from among more than five thousand research books, book chapters, articles, and reports related to the MENA region between 1990 and 2023, and we are expanding the corpus of work.3

If you talk to almost any academic about publishing, you’ll hear frustration. Even under ideal conditions, disseminating scholarly findings and integrating them into the body of humanity’s collective knowledge is difficult. And most agree that we are far from ideal conditions, even if they cannot agree on what those ideal conditions might be.

A major concern of social scientists is bias in the dissemination and integration of research. These are often treated separately in the literature, with some studies focusing on dissemination by analyzing publication patterns and others focusing on integration by tracking citation patterns. We see these as intrinsically linked processes. Obviously, publication affects citation, so biased dissemination is a precursor to biased integration. But citation itself is also a form of dissemination, allowing scholars to incorporate others’ work into their own and disseminate it through publication.

In the social sciences generally, the dominant concern of recent years has been about gender bias in publication and citation. Recent scholarship has documented that patterns of publishing and citation in the social sciences can be biased against women, mirroring other gender biases in academia.4 This research has extended beyond publication to look at dissemination through other important modes, such as graduate seminar syllabi.5 However, unlike many other fields, there is no detectable gender bias in citations in the MENA social sciences.6

Among MENA scholars working at U.S.-based institutions, the dominant concern is methodological bias, reflecting a long division between qualitative and quantitative researchers.7 We see evidence of methodological divides, but we do not conclude that these are the main cleavage in the MENA social sciences, nor the only one that scholars should be focused on fixing.

Among MENA scholars concentrated in the MENA region, the dominant concerns are about language biases. We synthesize these concerns into three broad theories of what creates and reinforces language-based research hierarchies in the MENA social sciences: exploitation, incommensurability, and inaccessibility.

Exploitation. A prevailing view is that scholars outside the MENA region and writing in English often do exploitative, smash-and-grab, fad-chasing work that disregards local scholars. Sociologist Mona Abaza decries the “unequal academic relationship between so-called ‘local’ and Western experts of the Middle East,” in which researchers based in MENA are treated like research assistants for Western-based “academic tourists.”8 Abaza reports, “Many of us have been bombarded by emails from Western colleagues [requesting] such service.”9 This exploitative attitude is reproduced in a hierarchy of citations, in which Western scholars cite each other to “create the theoretical, informational, or/and analytical center” while failing to cite MENA-based scholars, “thereby delegitimizing their positions as knowledge producers at the international level.”10 These concerns fit into a larger decolonial critique of academic organization that presses for an expanded canon, more diverse syllabi, and multilingual calls for research funding.11 According to this view, the substantive research priorities of MENA social science would be different if the interests of local researchers were given parity in the processes of research dissemination and integration. Western-based scholars enjoy a “hegemony in science” that endows “the capacity to influence the choice of topics in the worldwide agenda.”12

Incommensurability. Additionally, researchers in and out of the MENA region may not engage each other’s work because it is incommensurable theoretically and methodologically. It is perhaps obvious that scholars who do not understand each other’s work will cite each other less. Scholars who understand each other will naturally form research communities with dense citation networks within the community and sparse networks outside the community. These communities will gravitate toward academic journals where their approach is understood and select journal editors who will prioritize publishing work that is intelligible for the community. These editors may feel that editorial processes that exclude work from incommensurable research traditions are justified: it is good stewardship, not malicious gatekeeping. All of this will discourage researchers from reading work they don’t understand, making it even harder to bridge the divides.

Styles of theory, argumentation, and evidence-gathering may differ between English-language and Arabic-language social sciences. For example, many MENA-based scholars publish research that does not rely on fieldwork, while much of English-language social science does.13 Norms of research methodology differ in other ways across these research communities too, so it is not always clear how studies in English and Arabic should inform each other even if they were all written in the same language. If MENA scholarship in Arabic and English is largely incommensurable, then cross-language citation will likely only increase with homogenization of research norms or increased acceptance of methodological pluralism.

Inaccessibility. A third possible cause of poor scholarly integration is inaccessibility. Foreign researchers are potentially ignorant of relevant work in local languages because the language barrier makes it difficult to read and they do not encounter it without intentional effort. The different career incentives of Western and MENA-based scholars discourage even those who can write in both English and Arabic from doing so. MENA-based scholars have to choose between publishing in English to have global impact or in local languages for local impact.14 Other modes of circulation—conferences, invited talks, social media—are more difficult across languages. And because scholars learn what they should cite from seeing citations in other papers, the effects of inaccessibility compound.

If accessibility is a binding constraint for integrating social science across languages, then rapid integration might be possible. Translation could improve cross-language accessibility in the MENA social sciences. Thus far, the impact of translation efforts has been limited. “While there is a move toward encouraging translations, only 2% of the articles in the sample are translated from their original language. The journal Contemporary Arab Affairs accounts for most of these articles, the majority of which are originally written in Arabic and translated into English.”15 Translation is expensive, at least via traditional means.

Nudges—design changes that make certain choices more likely without constraining options—can increase rates of cross-language citation. “The amount of references used in Arabic increases when the supervisor encourages his or her students to use them: 43% versus 14%.”16 Yet nudges presume that scholars have some way to access the content of foreign-language scholarship, through their own language ability or through translation. Nudging without translation will at best lead to superficial citations.

There are strong reasons to believe that exploitation and incommensurability are also to blame for the poor integration of social science across languages. Change will require a critical mass of MENA scholars writing in English, wherever they are based, to increase the professional rewards for citing non-English scholarship. Editors of scholarly journals and presses play a crucial role because their decisions about how to review and publish research are directly connected to scholars’ professional incentives. Translation and nudges toward cross-citation can only be effective if there are mutually intelligible research findings that could be connected and if scholars respect each other’s knowledge production. We argue that it is nevertheless worth attempting to improve accessibility to see how far we can get. If accessibility is no longer a barrier, then efforts to address other persistent causes of poor integration are more likely to succeed.

Inaccessibility is a plausible factor in our personal experience of dissemination and integration failures. Here, one of us reports an autoethnographic account of a “missed connection” as it unfolded, edited for clarity and length, with citations added.

Rich Nielsen, 7:45 a.m.–9:55 a.m., December 16, 2023, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States of America, the kitchen table where I write.

Sari Hanafi, a prominent sociologist based in Beirut, writes in both Arabic and English. I have admired his work since we were introduced to each other by Lisa Anderson as part of a working group examining the ethics of research dissemination in the social sciences of the MENA region. This morning, while writing this essay, I checked his Google Scholar page to see how his Arabic writing is listed there. The default landing page ranks his publications in decreasing order of citations. I assumed that Arabic writing wasn’t listed because, at first glance, no Arabic text appeared on the screen. Then I realized that several Arabic-language articles were in fact listed, and I immediately found one relevant to my research on religious authority: “‘We Speak the Truth!’: Knowledge and Politics in Friday Sermons in Lebanon,” published in 2017 in the journal Omran, free from the Doha Institute.17 The English-language abstract provided by Omran is so relevant to my interests that I immediately stopped writing and began to read. Hanafi’s article is imminently relevant to my book Deadly Clerics and subsequent essay, which both rest on the claim that Muslim clerics view themselves as academics.18 Hanafi’s article was exactly what I needed to cite to lend authority to that claim; it even has tables breaking down the academic training of preachers in Lebanon, mirroring tables in my book. Yet I am learning about this paper for the very first time today, in 2023. If it had been published in English in a journal from which I receive emailed article alerts (say, Politics and Religion or The International Journal of Middle East Studies), I think I would have been citing it for years. As of today, Google Scholar shows it having no citations. A translation republished in Contemporary Arab Affairs has four, a fact that itself speaks to the importance of translation.19

How did I miss this work despite the article being indexed by a platform I use for literature searches and despite my great interest in the content? I should have known about Hanafi’s work before now; it was my responsibility. But my “missed connection” shows how academic technology undercuts the dissemination and integration of social science research across languages. I can rule out incommensurability and, I think, exploitation. While there are major differences in research traditions that can make it difficult to integrate the work published in Omran on Hanafi’s side and the American Journal of Political Science on mine, this is not one of those cases. The problem is not strictly that Arab researchers do social science differently. I see Hanafi’s work as entirely compatible, and in the same research tradition as mine. Malice? I don’t think so. I really like Hanafi, and I really like this paper I just found. Laziness? I’ve been trying to collect everything I can find about religious authority in Islam and especially its connection to Islamic academia. I don’t remember encountering this article in my prior searches on Google Scholar.

Instead, I perceive (though I am skeptical of my own perceptions) my missed connection to be a result of technical and social systems. Google Scholar ranks articles by citation, so I was funneled toward other work. This article was listed 189th, and I noticed it only because I was looking specifically for his articles in Arabic-language journals that I expected would have few or no citations indexed by Google Scholar. Based on my previous search history, it appears the furthest I got on Hanafi’s page was item 100. Ranking papers by citation reinforces rich-get-richer dynamics.

I don’t get email journal alerts from the Arabic-language journal in which Hanafi published this article. Why not? Because I’m already drowning in emails, I primarily get alerts from journals where I hope to publish (though there are exceptions, I get alerts from American Ethnologist even though my work will probably never meet the standards to be published there).

Although my work is related to Hanafi’s, we have (to my knowledge) never published in the same journal. Thus, the peer review process did not encourage me to discover Hanafi’s article. We work in different disciplines—Hanafi is a sociologist; I am a political scientist—so editors are unlikely to know Hanafi well enough to ask him to review and reviewers are less likely to point me to his work.

Accessibility made a difference. The English-language title and abstract provided by Omran greatly decreased the effort I expended to realize that it was highly relevant to my research. I can’t easily skim in Arabic—I have to read every word. I was immediately able to access the article because Omran is open source and I quickly realized the importance of the data in the tables. Without immediate access, I would have likely made a note to return to this article later, but failed to. For me, work needs to be immediately available in my moment of intense curiosity.

Reflecting on my embodied experience, I was sitting in the chair where I do my best thinking: a hard plastic Ikea piece that sits at the end of my kitchen table where I can alternately write and stare out a large glass sliding door at the New England forest that abuts where I live. It is the place I find auspicious for making connections, having new thoughts, and being creative, and maybe that helped. Instead of writing what I intended to, for a piece that was already extremely late, I got sidetracked, based on a whim and a question about how Google Scholar indexed Hanafi’s Arabic-language research. The title activated the energetic curiosity of the flow state of research. I was driven to dig in, realizing that this is exactly the type of interaction I think is needed to foster cross-language knowledge dissemination and integration. I have felt excitement about the work I found, meta-excitement about its relevance to cross-language integration, and joy in an unexpected new direction for an essay where, frankly, I was a bit stuck. I felt shame that I didn’t know about the article and genuine puzzlement about how this is even possible. My emotions about my Arabic-language skills also came into play: I was happy that I can read more of Hanafi’s article than I thought, but frustrated at my inability to skim it as quickly as papers in English and my insecurity about not being as fluent as I want in a language that is central to my research. But my dominant experience was the exciting flow of research; I believe this is what makes for enduring integration of scholarly knowledge.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is both a buzzword and a punchline. There is tremendous optimism that AI can solve hard problems, and a joking recognition among technologists that AI is being proposed as the solution to every hard problem. If journal editors and reviewers start asking, “Is there relevant research in local languages that you should cite in your research?” scholars will turn to increasingly accessible AI tools such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT for guidance. But these generative AI tools, while appearing to give sophisticated answers, currently fail to solve the problems of integration.

To test, we asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT (3.5) for article and book citations in English and Arabic to add to an article on the topic of female Salafi preachers in Islam, and included the abstract and introduction of Nielsen’s article on the topic to mimic how we might have used the AI tools at our disposal if this were a manuscript in revision.20 In English, ChatGPT provides mostly sensible results, including seminal work by anthropologist Saba Mahmood that is cited later in the Nielsen paper.21 ChatGPT’s answers skew toward general, widely cited works, but it does seem like new, free generative AI tools could help a scholar find relevant, overlooked citations. The Arabic-language citations from ChatGPT appear even more interesting at first glance. Titles like “Salafi Women between Traditions and Challenges: An Analytical Study of the Role of Women in the Salafist Movement” appeared so relevant that we immediately tried to track it down. But as far as we can tell, the article does not exist, and neither do any of the other apparently helpful Arabic-language references from ChatGPT.

Phantom citations are a “tell” of generative AI. The large language models on which tools like ChatGPT are based are primarily prediction models: they take in large amounts of data and attempt to predict sequences of words. ChatGPT is a “black box,” so we can’t explain precisely why it provides English-language citations that exist and Arabic-language citations that don’t, but it is almost certainly because the input data include the English-language publications. Because it primarily predicts what a human might say in response to a prompt, it can provide references to works that appear frequently enough in existing academic citations. But large language models are even worse for changing inequitable citation patterns than Google Scholar’s default of presenting highly cited work near the top. Whereas Google can at least index work that has no citations so intrepid users can hunt through them, ChatGPT is inherently unable to predict that a human would provide a particular citation if that citation did not appear in the input data. It turns instead to predicting words that might make a relevant article and, as our initial interest in the articles showed, there it “succeeds.” But large language models will never subvert a citation hierarchy because they are trained on the existing scholarship that created that hierarchy, including preferential attachment to highly connected nodes in citation networks.22 Using ChatGPT to recommend citations is the essence of the rich-getting-richer.

Domain-specific, nongenerative AI offers a more promising way forward. We have created an online tool called “Finding MENA Scholarship in Arabic and English” that demonstrates the benefits of incorporating domain-specific knowledge into the task of recommending citations rather than training a massive model to predict them.

Our tool, which we built for a minuscule price compared to ChatGPT, outperforms it, at least as of this writing. The building blocks of our model are simple. We develop databases of scholarship in English and Arabic so that every citation we recommend is real, we use AI tools for machine translation and content matching, and we present the results in order of topical similarity rather than ranking by citations. What we present is merely a proof-of-concept and we acknowledge that it encodes our biases and blind spots. But it is open source and extensible. Anyone who thinks we are missing scholarship, providing inaccurate translations, or using a suboptimal model for predicting relevance can modify it.

Because it is open source and interpretable, our tool also provides insight into publishing trends in MENA social sciences. These trends, in turn, inform our understanding of why scholars publish what they publish and cite what they cite. We present the tool and then explain how the findings from its underlying statistical model inform our conclusions about the field.

Our pilot database comprises 5,437 publications in MENA studies broadly defined published between 1990 and 2023. The data encompass both English- and Arabic-language publications, and include a diverse array of disciplines: mostly political science, sociology, history, and anthropology. We include articles, books, and reports, aiming to provide access to all kinds of scholarly production. Table 1 shows a breakdown of the sources currently in our dataset. To look at MENA social science as it is produced locally, we include three journals published by the Center for Arab Unity Studies (CAUS), two in Arabic and one in English, for a total of 1,247 journal articles, of which 855 are in Arabic. These journals appear frequently in reviews of MENA social science publishing. There are others we do not currently include that we are working on adding, notably Omran, Siyasat Arabiya, Majalat al-Dirasat al-Falastiniya, and Al-Mustaqbal Al-Arabi.

| Genre | Language | Sources | Number of Documents | Disciplines | Dates | Publishers |

| Articles | Arabic | Idafat | 477 | Sociology | 2008–2020 | CAUS |

| Articles | Arabic | Arab Journal of Political Science | 378 | Political Science | 2006–2020 | CAUS |

| Articles | English | Contemporary Arab Affairs | 392 | Interdisciplinary | 2008– Adjusting for confounding with text matching | CAUS/ UCBP |

| Articles | English | International Journal of Middle East Studies | 1,138 | Interdisciplinary | 1990–2022 | CUP |

| Articles | English | Nine journals analyzed by Berlin and Syed | 274 | Political Science | 1990–2020 | CUP, OUP, WB |

| Books | English | CUP: Studies in Comparative Politics; Comparative Politics; Middle East Studies. OUP: Comparative Politics | 178 | Political Science and Interdisciplinary | 1990–2022 | CUP, OUP |

| Chapters from anthologies | English | OUP Middle East category | 181 | Political Science and Interdisciplinary | 2018–2022 | OUP |

| Reports | English | MERIP reports online | 2,419 | Interdisciplinary | 1990–2023 | MERIP |

The publishers are Cambridge University Press (CUP), Middle East Research and Information Project (MERIP), Centre for Arab Unity Studies (CAUS), Oxford University Press (OUP), University of California Berkeley Press (UCBP), and Wiley Blackwell (WB). The nine journals analyzed by Berlin and Syed are Arab Journal of Political Science, Arab Political Science Review, British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Science, Comparative Politics, International Organization, International Studies Quarterly, Journal of Politics, and World Politics. Mark Stephen Berlin and Anum Pasha Syed, “The Middle East and North Africa in Political Science Scholarship: Analyzing Publication Patterns in Leading Journals, 1990–2019,” International Studies Review 24 (3) (2022): viac027. Source: Authors’ data. | ||||||

In English, we collected all of the articles from the flagship journal of the Middle East Studies Association, International Journal of Middle East Studies, books and edited volumes published on MENA by two of the leading academic presses, Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press, and articles on MENA published in nine leading political science journals, coded by political scientists Mark Stephen Berlin and Anum Pasha Syed.23 We also include all of the reports by the Middle East Research and Information Project (MERIP) to compare topical coverage between academic scholarship and more policy-oriented reports.

Our dataset is larger and more diverse than recent studies of publishing trends in MENA politics (Table 1).24 We build directly on these studies by using replication data generously provided by Berlin and Syed so our tool and findings speak to those debates, but those prior findings are based primarily on approximately 275 political science articles.25 We add academic books, chapters from anthologies, Arabic-language journals, interdisciplinary journals, and reports. Despite this wider variety, our database covers only a portion of MENA studies scholarship and reflects our familiarity, biases, blind spots, and access. We are building ways for scholars to include sources we have not—the downside of our approach is that scholars can only find citations that are in the database and we do not have Google’s capacity to index scholarship. Still, our data are sufficiently varied to serve as the basis for a proof of concept and provide a richer picture of the field than previously known.

We use machine learning models to bridge language barriers through machine translation and as a recommendation system to compare the similarity of publications, including new works by an author. To use our tool, an author seeking citations enters text into a search box and the algorithm returns the publications in the dataset that are most similar topically, in both English and Arabic.

To include a publication in the tool, we obtain the full text of each publication when possible, or word counts from JSTOR. If the text is not machine-readable, we apply optical character recognition. Next, we use AI to translate Arabic into English, which serves as a pivot language. This is the most viable approach for cross-language analysis, but we acknowledge that machine translation errors could affect our results.26

To identify similar publications, we match topical content using a structural topic model and text-matching.27 A topic model identifies correlated clusters of words that summarize document content.28 There is no definitive answer to the questions “How many topics are in a research article and what are they?” so fitting a useful topic model is partly a matter of interpretation and combining statistics, and interpretation of these topics is subjective. Nevertheless, such a model can return results in seconds that would take weeks or years of reading to code qualitatively. The model is not a substitute for close reading, but it can make close reading more efficient by quickly informing researchers about the broad contours of a corpus, alert them to overlooked topics or concepts, and focus close reading on texts that are representative of broader trends in the corpus.

To get reading recommendations based on an existing text, a user inputs part of their chosen source text. The software applies the topic model to the input text to derive topic proportions and then returns closest matches on topics, regardless of language. We find that this drastically lowers the search cost of identifying relevant research. The onus remains on scholars to carefully read the work the tool recommends to see whether it merits citation, but scholars can’t cite work they don’t know.

To illustrate, we asked the topic model to identify the Arabic-language articles with the most similar topic proportions to Nielsen’s 2020 essay “The Rise and Impact of Muslim Women Preaching Online.”29 The matching procedure returns a ranking of similar articles: we report the top five in Table 2.

| Target (input): Richard Nielsen, “The Rise and Impact of Muslim Women Preaching Online,” in The Oxford Handbook of Politics in Muslim Societies, ed. Melani Cammett and Pauline Jones (Oxford University Press, 2022), 501–520. |

| Match 1: Mukhtar Muhammad Abdallaa, Nifin Muhammad Ibrahim, and Muhammad Fathallah Ebadallah, “هل الآراء نحو بعض قضايا النوع الاجتماعي تختلف من الريف إلى الحضر” [Do Opinions on Some Gender Issues Differ from Rural to Urban Areas?], Idafat 31–32 (2015): 99–117. |

| Match 2: Boubaker Boukhrissa, “الحضور النسوي بين أحضان التصوف المغاربي” [Female Presence Among in Maghrebi Sufism], Idafat 22 (2013): 132–146. |

| Match 3: Azza Sharara Baydoun, “في ’ المكان الصح ‘ ؟ : المرأة في القضاء الشرعي” [In “the Right Place”?: Women in the Shariah Judiaciary], Idafat 31–32 (2015): 62–84. |

| Match 4: Adam Jones, “الإبادة الجماعية المجندرة” [Gendering Genocide], trans. Lahay Abd Al-Hussayn, Idafat 43–44 (2018): 33–62. |

| Match 5: Muhammad Abu Rumman and Hassan Abu Haniyeh, “' النسائية الجهادية ' ' من القاعدة إلى تنظيم الدولة الإسلامية '” [“Jihadi Feminism” from al-Qaeda to the “Islamic State”], Idafat 41–42 (2018): 181–194. |

Source: Authors’ data. Richard A. Nielsen and Annie Zhou, “Finding MENA Scholarship in Arabic and English” (accessed February 20, 2025). |

The tool also provides matches in English. They are not necessarily better than the results from ChatGPT or Google Scholar. Our tool provides matches that are more specifically relevant, but is missing many important works and does not help researchers identify which are highly cited. But in Arabic, our results are clearly better than those from generative AI because they are real.

The dynamics we have labeled exploitation and incommensurability create constraints on scholarly dissemination and integration that a tool for cross-language citation recommendations cannot fix. Legacies of exploitation might mean there are no relevant citations for a given text if the topics, questions, and concerns that animate scholars writing in Arabic are fundamentally different than those animating scholarship in English. For example, jihadism is a focus of English-language scholarship in part because of U.S. government concerns and a long history of Orientalism. If scholars writing in Arabic do not write much about jihadism, then there will be no articles to match. By the same token, if Arabic-language research is theoretically and methodologically incommensurable with English-language scholarship, then authors will identify matches on substantive topics but find them methodologically incompatible.

Our topic model gives reason to hope that these constraints are not binding. We focus for a moment on political science, where our disciplinary experience positions us to judge best what might or might not be relevant to cite. When we compare Arabic-language and English-language political science research, we see large differences; the concern is valid. But the question is not whether these different research communities have identical research preferences, but rather whether there is enough overlap to integrate.

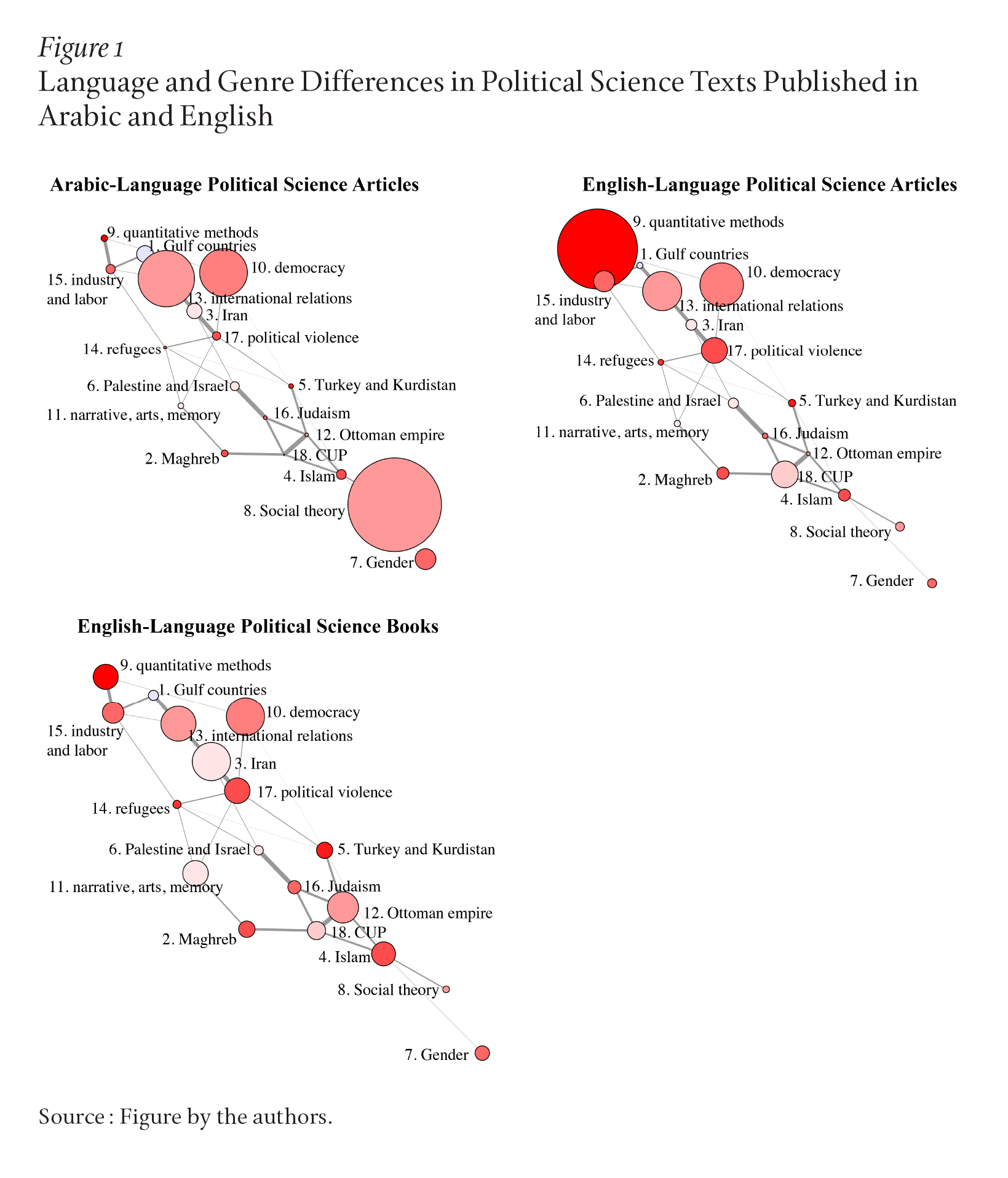

On the substantive topics that some viewed as oversupplied in English-language scholarship due to Orientalism, we find that Arabic-language scholarship also deals with these topics, at least enough for a conversation. We can see this by representing the topic model graphically, in Figure 1, where each disc represents a topic, the size represents the proportion of a corpus devoted to that topic, and the network represents which topics are most likely to appear together in the overall corpus.

We indicate the prevalence of topics by the size of each disc in the plot. The top left panel shows which topics are emphasized most in Arabic-language political science articles, the top right shows English-language articles, and the bottom left panel shows English-language books. We leave the network layout the same for all so that the visual difference in the sizes of the discs immediately highlights the variations. It is true that English-language scholars focus on democracy (topic 10) and political violence (topic 17), and these topics are also represented in Arabic-language articles. Islam (topic 4) and gender (topic 7) are actually as prevalent in Arabic as in English, belying the notion that these are particular concerns of Western scholars.

We can see this qualitatively in Table 2 as well, with gender and religion being well-represented in the titles of Arabic-language texts, which match to an English-language essay about female preachers in Islam. We would hardly say that this means the research questions Western scholars focus on are free of Orientalist tendencies, but the Arabic-language scholarship has kept up on these topics enough that more integration seems possible.

There is worse news about commensurability. The gap in theory and method yawns between Arabic and English political science. Scholars writing in Arabic devote a large amount of writing to a certain kind of social theory (topic 8) that is close to nonexistent in English-language scholarship. English-language researchers encountering articles with this style of theory will, we think, find it perplexing. In return, Arabic-language scholars will likely find that English-language scholars are not speaking to the same theoretical debate. By contrast, English-language political science articles are, true to reputation, focused on quantitative methodology (topic 9). But although this has widely been decried, what seems to be missing from the methods wars is recognition that English-language political science books do not emphasize quantitative methods much.30

We cannot anticipate how useful a citation suggestion tool will be for any particular researcher, but these general trends suggest that incommensurability will be the biggest barrier to reaching higher rates of integration in political science publications, if accessibility is improved. Because English and Arabic scholarship tends to have very different ways of writing both theory and method, this means the common denominator is most likely to be descriptive inferences and broad arguments. It will take work for scholars in each tradition to extract what is useful to them, even if they find scholarship that matches well on substantive topics. Still, there is at least some scholarship that is commensurable, as our autoethnographic description of a “missed connection” shows.

Whether this tool could change literature review norms is an open question. We expect that English-language authors facing harsh space constraints will be generally unwilling to cite work in Arabic unless there are professional incentives for doing so. These incentives are often applied by editors and reviewers, so that is the place to target change. A similar style of intervention by editors has shown to be effective for changing norms of citation with respect to author gender in international relations publications.31

Readers can access the tool and try it for themselves at https://rnielsen.shinyapps.io/shiny_menapubs. As we work to improve it, our top priority is expanding the database of publications. Because obtaining the full text of scholarly work may present practical and legal challenges, we will explore whether abstracts and keywords are enough for effective searching. With this tool in hand, authors will be better equipped to respond to or preempt an editor or reviewer who asks, “Is there relevant literature in local languages that you should consider citing?”

authors’ note

Thanks to Elizabeth Parker-Magyar, Sari Hanafi, Amel Boubekeur, Lisa Anderson, Rabab-El Mahdi, Jerik Cruz, and the entire REMENA group for many discussions of related issues. Thanks to Mark Berlin for providing data.