The Perils of Politicized Religion

In the United States, religion and partisan politics have become increasingly intertwined. The rising level of religious disaffiliation is a backlash to the religious right: many Americans are abandoning religion because they see it as an extension of politics with which they disagree. Politics is also shaping many Americans’ religious views. There has been a stunning change in the percentage of religious believers who, prior to Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy, overwhelmingly objected to immoral private behavior by politicians but now dismiss it as irrelevant to their ability to act ethically in their public role. The politicization of religion not only contributes to greater political polarization, it diminishes the ability of religious leaders to speak prophetically on important public issues.

In the contemporary United States, religion has increasingly become mired in partisan politics. Politicians routinely appear alongside religious leaders while campaigning and invoke their own religious bona fides as they appeal to voters. The connection between religion and partisan politics has become so pervasive in American politics that it is easy for Americans to forget that, in comparison with other liberal democracies, the United States stands apart. I was reminded of this myself when, a few years ago, I gave a lecture in Berlin on religion’s role in American presidential elections, a subject on which I lecture frequently to American audiences. The Germans in the audience were aghast as I explained how U.S. presidential candidates, Republicans in particular, regularly speak in very personal terms about their religious beliefs.

At the same time that religion and partisan politics have become intertwined, the United States has also been undergoing a “secular turn,” with more and more Americans identifying as not having a religious affiliation, and a smaller but still growing number adopting an affirmatively secular worldview. In their exhaustive analysis of the existing data on religious trends, social scientists David Voas and Mark Chaves conclude that “the evidence for a decades-long decline in American religiosity is now incontrovertible. Like the evidence for global warming, it comes from multiple sources, shows up in several dimensions, and paints a consistent factual picture.”1

This essay describes how these two trends are related, and why we should care. One consequence of the overlap of religion and partisanship has been a secular backlash: increasingly, Americans–especially young people–are abandoning religion because they see it as an extension of politics, specifically politics with which they disagree. As an empirical matter, the politicization of religion (and the religionization of politics) as well as the attendant backlash have been fascinating developments, as they contribute to our understanding of how religion and politics interact. However, the partisan inflection of American religion is not just an interesting empirical trend; it has troubling normative implications as well. Some may lament the growth of secularization; others may celebrate it. I take no position either way. Rather, my concern is with the social consequences of the politicized form of religion that has triggered the secular backlash.

One need not be an advocate for religion, or even a religious believer, to see the dangers of politicized religion. There are at least two reasons: First, the growing secularist-religionist cleavage is yet one more way that Americans are polarized. Given the deep-seated nature of a religious or secular worldview, such a cleavage has the potential to be especially dangerous. History shows that religious conflict–including, and especially, disagreement between the religious and the secular–can bring societies to a boiling point, even more so when those religious-secular divisions reinforce a political cleavage. Second, the more religion is wrapped up in partisan politics, the more it loses its prophetic potential. Religious voices are not always on the right side of history (sometimes they are on both sides or take no side), but nonetheless have a unique ability to raise a moral voice and to mobilize social action. For many Americans, Martin Luther King Jr. is the exemplar of a prophetic voice in our politics, but he stands among many religious leaders who, over the course of American history, have risen above the partisan fray to express a moral voice. Given the current state of our body politic, prophetic voices are needed now more than ever. Many religious traditions can speak to the troubles of our time, including economic inequality, racial prejudice, and callousness toward immigrants and refugees–inspiring Americans to find solutions to seemingly intractable problems. Even people with a secular belief system should appreciate that religion can serve to inspire and motivate people to bring about significant social change.

This essay answers a series of questions. In the contemporary United States, to what extent is religion perceived as partisan? What is the empirical research to support the argument that the partisan tinge to religion has led to a secular backlash? Why is the political fracture along religious-secular lines a threat to religious tolerance? How does the partisan perception of religion hinder its prophetic voice? What, if anything, can be done to change the status quo, so that religion transcends the partisan fray–perhaps serving as a force for lessening rather than exacerbating political polarization?

For a younger generation of Americans, it may seem obvious that religion and partisanship go hand in hand, since that is the only world they know. My undergraduate students, for example, have come of political age during a time in which the religious right is often described as the base of the Republican Party. To them, the partisan connection between religion and the GOP is an article of faith. Election commentary often features discussion of the “God gap,” or the fact that, in general, Americans who attend religious services regularly are more likely to vote Republican.2 Nor are these merely the mistaken notions of the chattering class: social science research confirms that religious commitment (measured in various ways) is indeed a strong predictor of identifying as a Republican. The connection between religion and the Republican Party has not formed by accident, but is instead the result of deliberate choices by strategic politicians, who saw an opportunity to wean many white religious voters away from the Democratic Party by emphasizing socially conservative issues like opposition to abortion and LGBT rights.

Many voters are like my undergraduate students, who have internalized the religious divide between the parties. In national surveys of Americans, far more say that “religious people” are more likely to be Republicans than Democrats; even more say that “evangelicals” are Republicans. In fact, when asked which groups are likely to be Republicans, Americans put evangelicals next to business people, traditionally the heart and soul of the GOP. Conversely, Americans also associate secularists with the Democratic Party, although not to the same extent that they link religionists with the Republicans.3 Notably, these partisan group associations are shared by Republicans and Democrats alike: that is, people on both sides of the aisle perceive the religious-secular divide between the parties.4 At a time when Republicans and Democrats agree on very little, this is a rare example of bipartisan consensus. Yet it is also important to note that a sizeable share of the American population does not perceive a religious-secular cleavage between the parties. Thirty-six percent say that evangelicals are “an even mix” of both Republicans and Democrats. More, 54 percent, say the same about religious people generally. Likewise, 55 percent perceive “people who are not religious” as split between the two parties. In other words, while there is undoubtedly a partisan division along religious-secular lines, there is still a significant portion of the electorate who do not see politics through a religious lens, suggesting that American politics is not locked into an intractable division between religious and secular Americans.

Furthering the point that the religious-secular divide is not a permanent feature of the American political system, it is also important to note that there are exceptions to the religion-Republican connection, most notably among African Americans. Black people are, on average, highly religious, and yet lean heavily toward the Democratic Party. The same is generally true of Latinos, although they are, on average, less religious than African Americans, and less likely to identify with the Democratic Party. While a much smaller share of the electorate, Muslim Americans are another group with a high level of religiosity who are also heavily Democratic. Thus, the talk of a God gap is largely a divide among white voters: a reminder that there is no iron law that links religion to only one party or political perspective. Readers of a certain age will also recall that the current religion-Republican connection is, in historical context, a relatively new development. As late as the 1970s, there was essentially no connection between voters’ degree of religiosity and their partisan leanings.5

These important exceptions notwithstanding, the fact remains that many voters associate religion with one of our two political parties. The public perception is significant for understanding voting patterns, voter mobilization strategies, and the policies that the parties are likely to support when in office. Yet the religion-Republican connection goes further than just the tendency for religious voters (especially those who are white) to identify as Republicans. To say that members of any religious tradition are likely to have a particular political view implies that it is the religion that leads to the political view; religion comes first. In other words, it suggests that voters’ religiosity pulls them toward the party that has spent a generation branding itself as the party favorable to religious interests.

There is also increasing evidence, both anecdotal and systematic, that politics shapes religious views. Instead of religion preceding politics, politics takes priority over religion, thus flipping the typical assumption of how religion and politics come together. As I explain below, the fact that many Americans prioritize politics over religion–whether consciously or unconsciously–is what drives the secular backlash to the rise of the religious right.

What is the evidence for the claim that politics often precedes religion? Consider two notable examples. One is Roy Moore, a Republican senatorial candidate in Alabama in 2017. Prior to running for the Senate, Moore had made a career out of being a cause célèbre within religious right circles. As the elected chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, he installed a two-ton granite monument of the Ten Commandments in the state judicial building. A federal court determined that it was a violation of the Constitution’s nonestablishment clause and ordered it removed. When Moore refused, the court expelled him from the bench. Moore then took the monument on a national tour, speaking to sympathetic audiences about how the United States is a Christian nation whose values are under attack by those espousing a secular view of the world.6 He again ran for the Alabama Supreme Court and won, but was again removed from the bench for defying the Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage.7

With this background, Moore ran for the Senate as the candidate of the religious right, an enviable distinction in Alabama, a highly religious state in which white evangelicals are a large constituency. However, instead of rolling easily to victory, he was soon embroiled in controversy. Multiple women came forward accusing Moore of having sexually harassed them as teenagers when he was an assistant district attorney in his thirties.

In light of these charges, many Republicans dropped their support of Moore. But not all. Among his most vocal supporters were various pastors, including Franklin Graham, son of Billy Graham. A group of over fifty pastors released a letter endorsing Moore, despite the evidence that he was a serial sexual predator.8 While Moore lost the election, exit polls revealed that he received 80 percent of the vote among white evangelicals.9

The second example of politics taking precedence over principle is a similar tale about Donald Trump’s campaign for the presidency. Many highly religious voters were slow to warm to Trump, and it was not hard to see why. He owns casinos, had long bragged about his extramarital sexual dalliances, and is often profane. While on the campaign trail, he demonstrated an obvious unfamiliarity with the Bible and the core tenets of Christianity. Eventually, though, religious Republicans–including but not limited to evangelicals–came to be among Trump’s strongest supporters. And they stuck with him even after the release of the Access Hollywood tape, in which Trump is heard bragging about how being a celebrity enabled him to kiss women without their consent and to grab them by their genitals. On election day, 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for Trump. To put that level of support in context, Trump received a higher percentage of evangelical support than George W. Bush in 2004 (78 percent), who is himself an evangelical.

Given the extraordinarily high level of white evangelical support for Trump, one might ask whether this story is really only about the politicization of evangelicalism specifically, and not religion more broadly. There can be no doubt that evangelicals are a “leading indicator” of how religion has become politicized. Not only are evangelical leaders the most vocal religious leaders in Trump’s camp but, as noted above, Americans are more likely to associate evangelicals with the Republican Party than simply “religious people.” Notably, though, this is not just an evangelical, or even Protestant, phenomenon. For example, among white Catholics, Trump received 60 percent of the vote, obviously lower than among evangelicals but still higher than white Catholics’ support of Mitt Romney in 2012, John McCain in 2008, or George W. Bush in 2004.

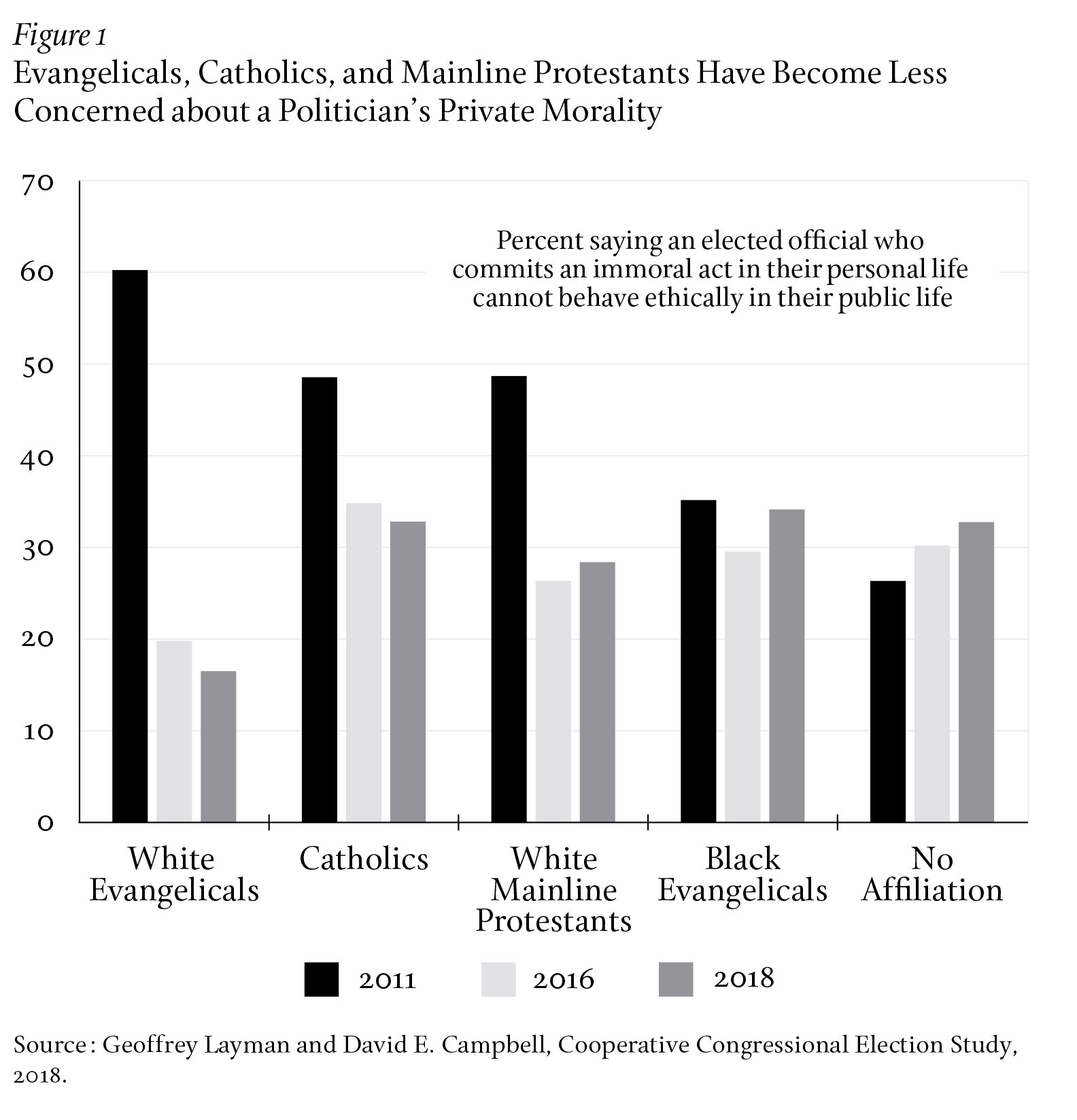

Both the Moore and Trump examples suggest that religious views can be subordinated to partisanship. Still, the vote is a blunt indicator, making it difficult to decipher people’s underlying opinions. No doubt many religious voters were casting a vote against Hillary Clinton rather than for Donald Trump. Fortunately, though, we need not rely on the broad brushstrokes of election returns to see how politics can shape the views held by religious Americans. Public opinion data provide finer-grained evidence. Back in 2011, a poll conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute and Religion News Service asked a nationally representative sample of Americans whether “a public official who commits an immoral act in their personal life” can still “behave ethically and fulfill their duties in their public and professional life.” This was just over a decade following the impeachment of Bill Clinton, when the nation was riven over the question of the connection between private and public morality. At that time, 60 percent of white evangelicals said that immoral acts in private meant that a public official could not be trusted to behave ethically in a professional capacity. This is to be expected, given the number of religious–especially, evangelical–leaders who argued for President Clinton’s removal from office owing to his adultery and his dishonesty when denying his affair under oath. Consider these words from Franklin Graham in a 1998 Wall Street Journal op-ed, which succinctly reflect the prevailing view of Clinton’s indiscretions among evangelical leaders at the time: “If [Clinton] will lie to or mislead his wife and daughter, those with whom he is most intimate, what will prevent him from doing the same to the American public?”10

This same question about private and public morality was posed in another national survey done in October of 2016, following the release of the Access Hollywood tape. Now, only 20 percent of evangelicals–Trump’s strongest supporters–said that private immorality meant a public official could not behave ethically in their professional responsibilities, a precipitous forty-point drop.11 White evangelicals were not the only ones whose opinions changed. Among mainline Protestants, there was a twenty-two-point decline in those who said that immorality in private meant unethical behavior in public. Catholics fell fourteen points, while black Protestants only dropped five points. In contrast, people without a religious affiliation became five points more likely to agree with the statement that immorality behind closed doors precludes ethical behavior professionally.

While these changes in attitude are revealing, are they long-lasting? Or did they simply reflect the heat of the 2016 presidential campaign, only to fade away after election day? To find out, my colleague Geoffrey Layman and I posed the same question on the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, a very large survey of the American electorate. As shown in Figure 1, we found that the results held steady. In fact, after two years of the Trump presidency, white evangelicals were slightly less likely to see a connection between private immorality and publicly unethical behavior: 16.5 percent, compared with 20 percent back in 2016. The views of mainline Protestants, Catholics, black Protestants, and people without a religious affiliation were virtually unchanged.

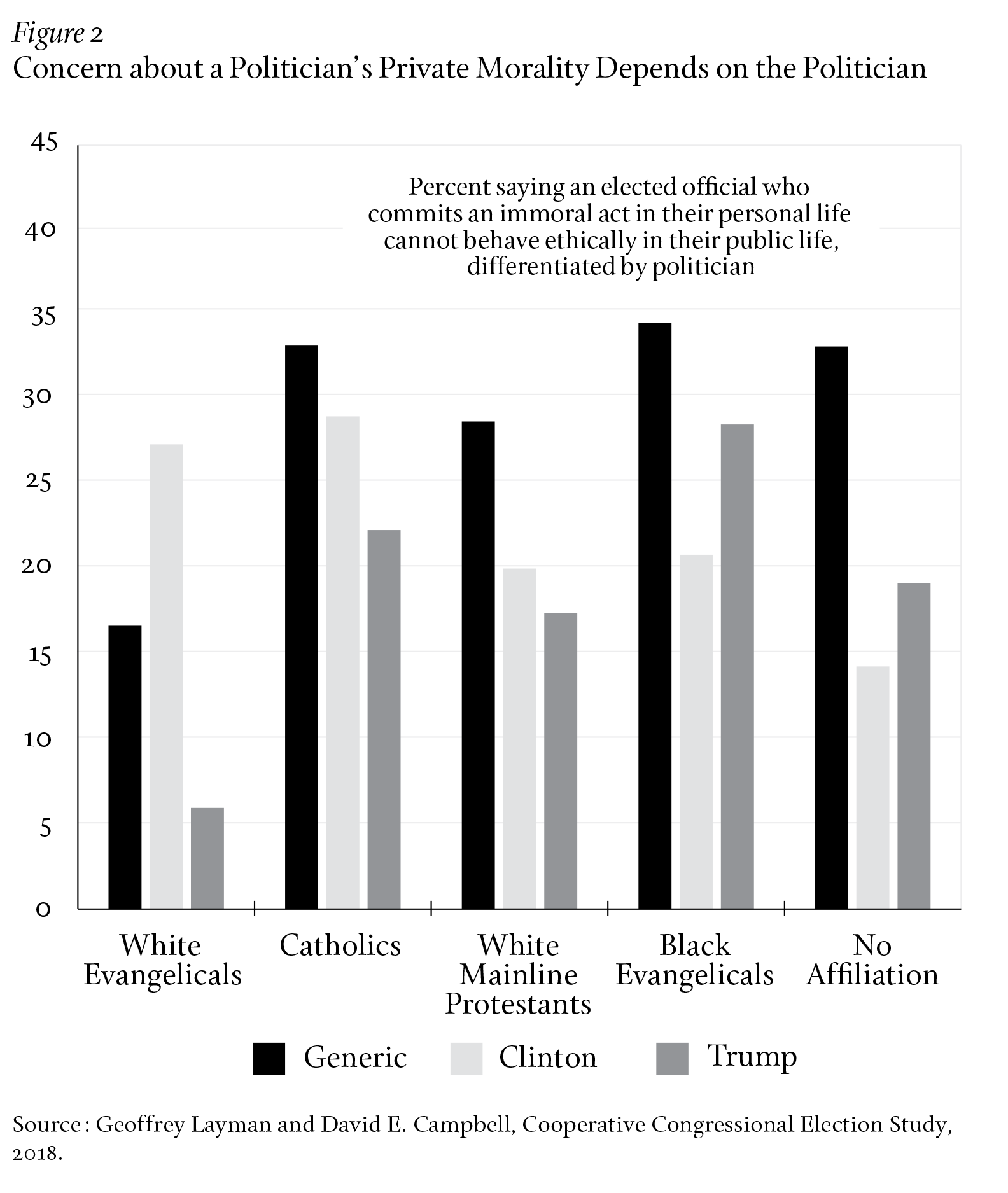

The point in highlighting the changing attitudes toward private immorality and public ethics is, of course, to suggest that the change is due to politics trumping (if you will) an opinion that is closely tied to one’s religious beliefs. To dig deeper into the connection between partisanship and views of public officials’ morality, we asked two other versions of the same question that prime respondents to think of either Trump or Clinton when answering the question. One begins with the statement, “Many supporters of Donald Trump have argued,” followed by the statement that a public official can act immorally in private but ethically in public. The other references the affair and impeachment of Bill Clinton by adding the prefatory statement, “When he was president, many supporters of Bill Clinton argued. . . .” Respondents were randomly assigned to receive only one of the three variations: the generic, Trump, or Clinton version.

As shown in Figure 2, when asked about Trump specifically, only 6 percent of white evangelicals said that there was a connection between private immorality and public ethics. In contrast, when primed to think about Clinton, 27 percent saw a connection: a difference of twenty-one points. Other religious groups also differ when asked about Trump or Clinton, but not to the same extent as evangelicals. Catholics were five points more likely to link private morality and public ethics when asked about Clinton; mainline Protestants were three points more likely. Lest one think that it is only Republican-leaning groups that shift their views depending on the politician in question, both black Protestants and people without a religious affiliation were modestly less likely to connect privately questionable behavior with public ethics when asked about Clinton–by eight and five percentage points respectively.

It does not take a political scientist to figure out what is going on here. Many people respond to this question according to their party affiliation, not out of principle. To underscore that point, we can compare Republicans to independents and Democrats. Both evangelicals and Catholics who identify as Republicans are far more likely to question the public ethics of a privately immoral official when asked about Clinton versus Trump. Among evangelical Republicans, the percentage who express concern about the professional behavior of someone who misbehaves in private rises thirty-four points when asked about Clinton compared with Trump. Among Catholic Republicans, the gap is even greater: forty points. The inverse is also true. Both evangelicals and Catholics who identify as Democrats or independents are more concerned about a private-public connection when asked about Trump instead of Clinton, although the differences are not as large as for their Republican counterparts: eight points for evangelicals and twenty-nine points for Catholics.12

In sum, we have strong evidence that many religious believers place party over principle when evaluating the public implications of behavior they find immoral. They put politics first.

Some readers may ask whether the influence of politics over religion is anything new. After all, religion has long been intertwined with American politics. Clearly, this is the case, but this should be cause for concern rather than complacency. It is precisely because of this history that we should be alarmed about stark political divisions along religious lines. In the past, there was political conflict between members of pietistic and liturgical faiths, not to mention the tensions between Protestants and Catholics.13 At times, these conflicts even led to violence. Such a legacy of religion-fueled discord should give us pause, as they are a reminder that differences rooted in religion can be explosive.

Still, the parallels with the past are imperfect. What is new about today’s political environment is that the partisan differences are not between religious camps, but rather between religion and secularity. One party has wrapped itself in religion, thus making religion, broadly construed, a source of partisan identity. The other has more quietly–and almost by default–come to be associated with secularism. While a few Democratic politicians have described themselves in secular terms, they remain few and far between. There is a “freethought” caucus within Congress, but it has all of four members, fewer than the Friends of Kazakhstan (which has ten). Most famously, during his 2016 presidential run, Bernie Sanders described himself as “not particularly religious,” a highly unusual admission in contemporary American politics. Yet he protested vigorously when leaked emails found some Democratic officials describing him as an atheist.

Republicans’ identification with religion qua religion, and the Democrats’ secular mirror image, has had far-reaching implications for both the religious and political landscape of the country. Perhaps the most significant consequence of the perception that religion has become an extension of politics has been its contribution to the nation’s recent “secular turn.” Over roughly the last twenty-five years, there has been a rapid rise in the percentage of Americans who report not having a religious affiliation. Until the early 1990s, the percentage of Americans who do not identity with a religion hovered between 5 and 7 percent–small enough that few observers paid much attention to them. Then, beginning in the early 1990s, that percentage began to rise. By 2000, it was 14 percent; in 2010, it reached 18 percent; and in 2018, it had grown to 23 percent.14 This sudden growth is puzzling, as most theories of secularization posit a process of generational replacement, whereby a population secularizes gradually as older, more-religious members die off and are replaced by younger, more-secular cohorts. This has been the pattern in most other advanced industrial democracies. What explains the anomalous American case?

In a prescient article published in 2002, sociologists Michael Hout and Claude Fischer proposed an explanation for the rise of the religious Nones, as those without an affiliation are often called: a backlash to the religious right.15 They suggested that the mixture of religion and partisan politics had led an increasing number of Americans to disclaim a religious affiliation. Specifically, moderates and liberals were turned off by religion because of its association with conservative politics. As they put it, “Organized religion linked itself to a conservative social agenda in the 1990s, and that led some political moderates and liberals who had previously identified with the religion of their youth or their spouse’s religion to declare that they have no religion.”

At the time, Hout and Fischer’s explanation was based more on the process of elimination than affirmative evidence in favor of their hypothesis. Like an Agatha Christie novel, they figured out “who done it” by ruling out all the other suspects. In the years since, their foresight has become more and more apparent, as increasing evidence has accumulated in support of the secular backlash hypothesis.

For example, a recent article has found that, across states, the percentage of religious Nones has risen most where there has been the most activity by political organizations associated with the religious right. Other analyses based on repeated interviews with the same people have shown that, over time, Democrats are more likely to become religious Nones. Conversely, Nones are not likely to start identifying as Democrats. Put another way, it is the partisan identity that shapes one’s religious identity or, more precisely, the lack thereof. Furthermore, that effect is only found among people who see a connection between Republicans and religion–further evidence that this is a backlash to the partisan connotations of religion.16

While these analyses of voters in their natural habitat are suggestive, there could still be alternative explanations for the apparent secular backlash to politicized religion. The most convincing evidence for a causal relationship comes from experiments in which the researcher has complete control over the conditions of the study, thus ruling out alternative explanations. To that end, my colleagues and I have conducted a series of experiments in which we expose people to examples of politicians who employ religious rhetoric, thus testing how they react. The design of the experiment is straightforward. First, we collect baseline data on individuals’ religious preferences. Then, roughly a week later, we have them read a news story that describes the Republican and Democratic candidates in a nearby congressional race. In some versions of the story, the Republican uses a lot of religious rhetoric, in others, it is the Democrat who does so, and in other versions, both do. There is also a control condition in which neither candidate mentions religion. Subjects in the experiment are randomly assigned to one version of the story, after which they are asked the same questions as in the baseline survey. With this elegant design, we can see whether individuals change their religious preference based solely on their exposure to the news story. Randomization ensures that we can be confident that any rise in religious nonaffiliation is due only to the experimental “treatment”: that is, being primed to think about the intertwining of religion with partisan politics.

Our results are completely consistent with the secular backlash hypothesis. We find that exposure to a Republican candidate who employs “God talk” leads to an increase in Democrats who report no religious affiliation.17 Lest it seem implausible that reading a single news story could cause people to abandon their religion, this sort of fluidity in their declared religious identity is consistent with other evidence showing that many Nones have an ambivalent religious identity, and move back and forth between identifying with or disclaiming a religious affiliation.18

In other words, multiple streams of evidence have converged toward the same conclusion. It is not just that the United States is becoming a more secular nation. It is that Americans’ secularization is, at least in part, a backlash to the employment of religion for partisan ends. The widely held perception that religion is partisan has contributed to the turn away from religious affiliation. As is always the case with social scientific research, one can question the findings or methodology of a given study, but it is hard to argue when different studies using different methodologies, covering different time periods, all point to the same conclusion.

The decline in religious affiliation, however, is only the tip of the secular iceberg. While an important social trend, disaffiliation from religion is a very thin measure of secularization, especially as many Nones are what Hout and Fischer have called “unchurched believers.” That is, they retain some traditional religious beliefs, particularly a belief in God, even if they are unwilling to identify with an organized religion. In order to better understand the depth of secularism within the American population, my colleagues and I have developed a set of measures to gauge the degree to which individuals adopt a secular identity (such as atheist, agnostic, humanist, secular), receive guidance from nonreligious sources, and endorse a set of secular beliefs.19 Together, they form a scale of personal secularism.20 While we have a much shorter time trend for these measures than for religious nonaffiliation, from 2011 to 2017, we observed a rise in this more robust form of secularism compared with the growth in the Nones. Furthermore, we also find a two-way relationship between secularism and political attitudes. Over time, being on the political left leads to more secularism, just as it leads to religious nonaffiliation. However, unlike nonaffiliation, this sharper-edged secularism also affects political views. In other words, the evidence points to a mutually reinforcing relationship between secularism and politics: more of one leads to more of the other.

For empirically oriented scholars, the secular backlash to the religious right is an interesting phenomenon–an explanation for one of the most significant social trends in the last thirty years. Within the literatures in political science and sociology (including my own work), these findings are typically framed in positivist terms. Here, though, I wish to make a normative argument. My concern is not the rise of secularism per se, as I will leave others to debate the merits of secularity versus religiosity. Instead, I worry about the politicization of religion and the attendant secular backlash because this state of affairs does not bode well for the state of religious tolerance in contemporary America; it also diminishes the ability of religious leaders to speak prophetically about issues of public policy.

In our 2010 book American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, Robert Putnam and I showed that religious tolerance in the United States was relatively high, despite the fact that the United States combines high levels of both religious diversity and devotion. The explanation for this puzzling combination of devotion, diversity, and tolerance, we argued, was the near-ubiquity of social “bridging” among Americans of different religious perspectives, including between believers and nonbelievers. Interfaith neighborhoods, friendships, extended families, and even marriages have become the norm. As people of different religious backgrounds (including no religion) form close friendships and familial bonds, they become more accepting of those who have a different worldview.

Today, I fear that the conditions for religious tolerance that Putnam and I described are disappearing. If a religious-secular divide is combined with a deep partisan cleavage, the result could be a deterioration in Americans’ degree of religious tolerance. There are at least two reasons to think that this might be the case. First, while Putnam and I found that people of different religious backgrounds often comingle, other evidence on the partisan cocooning of Americans suggests that this sort of interaction is becoming less common. If religiosity and secularity are closely aligned to Americans’ partisan identity, we would expect Americans with religious and secular worldviews to have less contact with one another, given that people with differing political views increasingly inhabit different social spheres.21 Second, even if there is interaction between religious and secular Americans, injecting politics into the mix makes for a combustible combination, given the mutual antipathy Republicans and Democrats have toward one another. In other words, compared with a decade or so ago, I suspect that religious and secular Americans are less likely to associate with one another and, when they do, are less likely to have the sort of interaction that fosters comity over contention. I readily concede that, at this point, this conclusion remains conjecture, to be confirmed with empirical evidence. But it seems more likely than not.

As a hint that religious-secular discord is increasingly shaped by political views, consider that since at least 2006, there has been a growing connection between Americans’ partisan identity and their attitudes toward atheists. In the mid-2000s, there was little to no connection between partisanship and how people viewed atheists. By 2017, there was a sharp division: Republicans held a far more negative view of atheists than Democrats. Nor is this polarization in attitudes limited to atheists–admittedly, a relatively small share of the U.S. population–as Republicans and Democrats have also come to differ in their perceptions of nonreligious people, a more benign way of describing someone who is secular that applies to a far larger share of the population.22

A skeptic might ask whether this partisan-inflected antipathy is all that worrisome, or at least if it warrants any more concern than the many other ways that political polarization has divided Americans. I suggest that it should not be dismissed as just one more source of division: the religious divides in our politics now stand in sharp contrast to the past high level of interreligious acceptance among Americans in their personal lives. Now, however, it appears that politics has come to infuse the relations between religious and secular Americans. It is one thing to have a political disagreement with your family, neighbors, and friends: those political differences are couched in personal relationships that subsume politics. In our current state of polarization, fewer and fewer Americans have such crosscutting social relationships. Americans’ party preferences align with where they live, where they shop, and the media they consume. Add to this an alignment with one’s religious or secular worldview and those divisions burrow even deeper.

There is another reason why the politicization of religion should cause alarm for religionists and secularists alike: the weakening of religion’s prophetic voice on matters of public policy, both in the sense of looking ahead and commenting critically on the present day. Historically, religious leaders have often spoken to the better angels of our nature, independent of any association with a political party. Admittedly, this has not always been the case, as we should not romanticize the role of religion in American politics. Sometimes religious leaders have stayed silent in the face of crisis or stood on the wrong side of history. Yet in their finest moments–including the abolition and civil rights movements–religious voices have nudged the nation toward a more perfect union. Even secularists who may not endorse its religious motivations should appreciate such advocacy. Politics, after all, makes strange bedfellows. However, religious leaders can only speak prophetically if religion is not seen as merely an extension of partisanship. Religious leaders must be willing to transcend partisan divisions as they speak to the problems of our day.

In today’s politics, where might religious leaders be able to contribute to public discourse? While this list is hardly exhaustive, religious texts have a lot to say about economic inequality, stewardship of the earth, racial harmony, and immigration, not to mention war and poverty.

I concede that a superficial reading of my argument could be construed as a call for a stronger religious left. That inference, though, is wrong. While religion today is perceived–correctly or not–as aligned with the political right, it would be equally problematic if religion were so tightly intertwined with the political left. It is just as much a problem if people on either side of the political spectrum put their party over principle. The key to religion’s prophetic potential is to not be perceived as being on one side or the other. Indeed, given the multiplicity of religious voices in the United States, I would expect religious leaders to take a wide variety of political positions: left, right, and center.

There will no doubt be readers who object to the characterization of religion as being concentrated on the right, as there are numerous examples of religious Americans who are forceful advocates for the left. And there are still others whose politics do not align with the left-right, Democratic-Republican American political spectrum. Some could even be called prophetic. While all of this is true, recall that the public perception of religion is partisan, and primarily on the right. The examples that cut against the general trend that I have described here have, for the most part, not seeped into the public consciousness. The reason for this is probably a matter of proportion. The sheer volume of conservative religious rhetoric–amplified by media such as Fox News, right-wing talk radio, and social media influencers–simply drowns out the voices on the left, in the middle, and those above the fray altogether. One might say that religion has been weaponized by the right.

What then, if anything, can be done about the politicization of religion? The answer lies in what appears to be driving the secular backlash. It is less what the religious leaders are doing and more the behavior of politicians.

Recall the experiments my colleagues and I conducted that showed that religious disaffiliation can be triggered by the mixture of religion and partisan politics, specifically in the Republican Party. There is an important nuance in our findings: while we observe a secular backlash when subjects read about politicians who employ religious rhetoric, we do not see a comparable effect when clergy speak out politically. In other words, voters are not as bothered by religious leaders who cross over into politics than by politicians who co-opt religion. While admittedly tentative, this evidence suggests that the end of politicized religion will only come if or when politicians change their behavior, specifically by no longer deploying religion to court voters.

There is an irony here. The prophetic voice of religious leaders has been compromised by the actions of politicians. But this irony also points to a solution. What if religious leaders refuse to allow themselves to be co-opted by politicians, and speak out against the mixture of God and Caesar? This would mean no clergy appearances at campaign events; no invitations for politicians to speak in their houses of worship; no supportive speeches, articles, posts, or tweets. It would also mean that politicians risk criticism from local clergy–voters’ own priests, pastors, and rabbis–for trying to mix religion with their politics.

While a rebuff from clergy would be an important start, however, it is not enough. Change will only come when politicians no longer see the status quo as helping their prospects for reelection, when their old ways cause them to lose more votes than they gain. At first blush, this may seem like a quixotic suggestion. Over the last generation, religion has become deeply embedded in our politics, especially among conservatives. Why would we think that politicians would change what is working for them? After all, politicians are notoriously loath to do anything to disrupt the status quo under which they were elected.

The most persuasive approach would be if voters in the center and on the right–especially those who are religious–snubbed politicians who deploy religion. If voters refuse to vote for, contribute money to, or campaign on behalf of politicians who exploit religious faith, those politicians will quickly change their tune. Such a negative reaction from voters would be the most powerful incentive of all. No politician can afford to alienate their base.

Is it realistic to think that such change is feasible? I remain optimistic that there is indeed hope. After all, weaponization of religion on the right is a relatively recent development in American politics. And recall that it is not found in most other liberal democracies. Nor is it even a completely accurate inference for voters to draw in the United States, as there are many examples of religious voices on the left, both in the present and the past, which is undoubtedly why many Americans do not perceive religion to be the province of one party over the other. The very fact that a sizeable share of Americans does not associate religion with one party over another means that the perception of politicized religion is far from universal. However, the end of politicized religion, and the religionization of politics, will require some consciousness-raising. Religionists and secularists alike need to recognize that the mixture of religion and partisan politics both threatens the state of religious tolerance in America and muffles religion’s potential to be a prophetic voice.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

Much of the work discussed in this essay has been in collaboration with Geoffrey Layman and John Green. I am grateful for their insights, although they should not be held responsible for any of my normative conclusions. Some of the data was collected through a grant from the National Science Foundation (Award 0961700). In addition, my work has been funded by an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship.