In Their Shoes: Health Care in Armed Conflict from the Perspective of a Non-State Armed Actor

The protection of health care in armed conflict dates to the 1864 Geneva Convention. Yet violations of international humanitarian law related to the protection of health care occur on a near daily basis, and conflict actors continue to obstruct health care actors from assisting people in need in conflict areas. An estimated one-third of the recorded threats affecting health care are attributed to non-state armed actors (NSAAs). Yet given that many NSAAs themselves do in fact provide and facilitate health care, this essay considers NSAAs not just as threats but, in line with international human rights law, also as potential facilitators, providers, and promotors of health care. We discuss the specific case of Northeast Syria, where one NSAA has de facto control of the territory, and examine the level of involvement of NSAAs in the respect, protection, and provision of health care. We also explore some opportunities and challenges in engagement between humanitarian actors and NSAAs on health care provision, with an emphasis on seeing health care from the perspective of the NSAAs themselves.

In addition to the devastating casualties caused worldwide in armed conflicts every year, a broader set of negative health effects plagues the populations in conflict areas. These include “long-term physical disabilities and mental health problems, increasing rates of epidemic diseases, substantial reductions of public health budgets, the departure of trained medical professionals, and the interruption of medical and food supplies.”1 The right to heath care in conflict areas and the protection of health care facilities and providers in armed conflict date back to the very first Geneva Convention of 1864. Yet we read about violations of international humanitarian law (IHL)—including access to health care—on a near daily basis.

An estimated one-third of the recorded threats affecting health care are attributed to non-state armed actors (NSAAs).2 In order to address the impact of these NSAAs on civilians in conflict, an entire “engagement” or “negotiation” industry has developed, dedicated to improving the efforts of the international community to influence these conflict actors, to reduce abuses, and to advance protection. This essay investigates whether turning the equation around and seeing health care provision from the perspective of the NSAAs themselves can assist in improving the provision of health care in conflict settings. NSAAs do provide and facilitate health care, but what are their challenges, opportunities, and interests when doing so?

In addressing this question, we join a growing effort to consider NSAAs not just as a threat to health care delivery, but also as facilitators, providers, and promoters of health care, with their own objectives, strengths, challenges, and weaknesses.3 We also acknowledge that contemporary NSAAs are operating within a context of multiple actors and situations of nonrespect of IHL and standards related to health care provision.4 By consulting both academic and policy literature on NSAAs, and based on our own direct experience as founding directors of Fight for Humanity, we aim to contribute to more effective engagement with NSAAs on health care provision, particularly in places where an NSAA has stable control of territories (full or partial). More specifically, we draw on Fight for Humanity’s work in Northeast Syria (NES) on child protection, where we were asked by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to support the development of their own policies for the protection of health care, as well as to improve their understanding of the broader humanitarian context, including interactions with humanitarian organizations.5 Given the situation of de facto control, the focus in this essay is on health care provision in an emergency and conflict situation, but where the main problems are linked to administrative, legal, and political issues, rather than the armed conflict itself or military attacks on health care by NSAAs.6 In short, the NSAA is controlling (most of) the health care facilities, and as such, there would be little incentive for them to attack them.

To better understand challenges to health care provision from the perspective of an NSAA, we consulted with the civilian wing of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) and the SDF, its military wing. In the analysis, we draw upon written questionnaires and messages exchanged with both the AANES and the SDF.

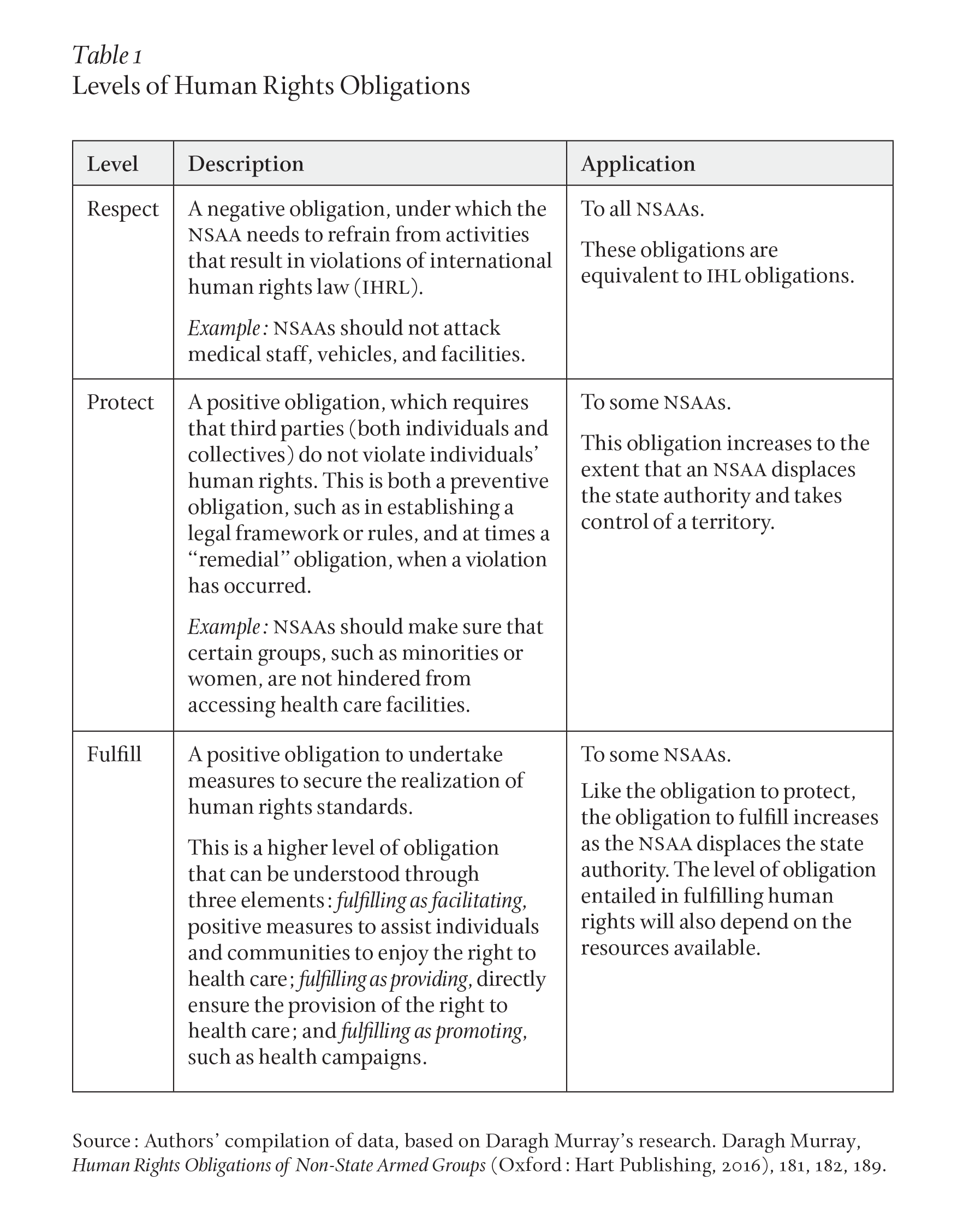

Academic literature and institutional practice have increasingly accepted that NSAAs have human rights responsibilities, at least when they control territory or exercise some form of governmental authority.7 Our own position, argued elsewhere, is that there can be no gap in people’s rights, and that therefore if the state is not able or willing to provide for the rights of a population, NSAAs controlling territory can and should do their utmost to do so, directly or indirectly.8 As a conceptual framework for identifying NSAAs obligations in the domain of health care provision, we employ human-rights activist and academic Daragh Murray’s “respect, protect and fulfil[l] framework.”9 Murray sees these three levels of obligations as interdependent, as shown in Table 1.

Notably, this disaggregation of obligations helps Murray to develop a “division of responsibility” between the state and the NSAA, with the state retaining “the overall responsibility for securing human rights obligations within the national territory.”10 In the cases in which the state cannot fulfill by providing, it should fulfill by facilitating. Thus, the state can never claim that full responsibility for meeting human rights obligations can transfer to an armed group. In line with Murray, we start from the assumption that the responsibility for health care provision lies primarily with the state, but can also be borne by an NSAA.

Here, a link can be made to the concept of “rebel governance,” which in international law and human rights scholar Katharine Fortin’s words refers to “the provision of public goods and the establishment of norms and rules regulating daily life in territory controlled by armed groups fighting in opposition to the government.”11 In terms of health care, the “public good” includes a spectrum of services: from military medics providing emergency care to the war-wounded, to the provision or facilitation of a variety of services such as maternity and neonatal care, regular check-ups, and surgeries. The public good can also be provided to a range of beneficiaries, including wounded armed actors and police forces; “regular” civilians including minorities, such as women, children, and people with disabilities; refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs); and detainees.

Murray considers health care as an example of a generally “resource intensive service” that may require interactions with the territorial state or other third parties for which “significant resources are required” to train and employ health care professionals, to maintain and operate equipment, machinery, and facilities, and to provide health education.12 Indeed, political scientists Reyko Huang and Patricia L. Sullivan find that NSAAs that receive external funding, weapons, or training are significantly more likely to provide education and health services to civilians.13

The obligation to respect, by contrast, is more dependent upon conduct than upon resources or capacity.14 In fact, the human rights obligation to respect health care does not go much beyond IHL obligations, notably the prohibitions against attacks on health facilities, vehicles, and personnel; sparing and aiding the wounded; allowing health personnel to operate independently according to the principles of IHL; and not disrupting supplies and services for health facilities. There are some existing tools for NSAAs to commit to the protection of health care, which are discussed elsewhere in this volume.15

The obligation to protect requires some capacity and resources—as well as territorial control—in the sense that NSAAs should, following Murray, assure that the health workers in the territories they control meet professional standards (in terms of education, skills, and conduct), and that third parties and harmful practices do not limit access to health care services (by providing and enforcing a regulatory framework on health care).16

At the end of the spectrum, fulfillment by provision can entail an NSAA assuming a state-like level of responsibility in relation to fulfillment of the overall right to health. One advantage with this, as Murray argues, could be the continuation and further development of the existing health system, rather than the establishment of a parallel system by humanitarian actors.17 There are also many examples of NSAAs that have been providing health care services to the populations when controlling or partially controlling territory.18

Yet there are also less resource-demanding ways for NSAAs to fulfill obligations in the health domain. Fulfillment by facilitation can be achieved through sharing information about health needs, coordinating action, or simply allowing access and operations. With respect to the latter form of fulfillment, NSAAs have allowed humanitarian access all over the globe, in contexts as diverse as Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Sudan, the Philippines, Mozambique, Somalia, Sierra Leone, Yemen, and the former Yugoslavia.19 NSAAs can also fulfill obligations by promotion, for example, through public health campaigns. While this aspect is not well documented in existing literature, examples have been plentiful during the COVID-19 pandemic and have been recorded in Geneva Call’s COVID Response Monitor and by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).20

The Taliban (until August 2021) is a case in point of fulfillment by facilitation. As argued by political scientists Ashley Jackson and Rahmatullah Amiri, the Taliban were largely open toward the provision of health services, particularly as a response to strong demand from the local population, and religious leaders could find no grounds to restrict access to health care—in contrast to other sectors, such as education, where access and provision were more restricted.21 For this purpose, they proactively engaged external actors and sought support to continue operating the health care system. Reportedly, the Taliban welcomed the opportunity to engage in health care provision and saw it as a priority, allegedly to show able and legitimate governance.22 Two conditions were nevertheless imposed on access: no credit should go to the Afghan government, and clinics should have no association with progovernment forces. Jackson and Amiri find that the relatively permissible attitude of the Taliban was largely related to the political and military pressure that its leaders were facing and their wish to respond to community demands for greater access to services, especially after 2014.23

In some conflict contexts, territorial control is split, and health services are provided by competing actors in the same territory.24 Political scientist Marta Furlan stresses that, to benefit from existing expertise, personnel, and infrastructures, and to be able to respond to people’s needs without paying the (full) costs of direct provision, NSAAs might choose to cooperate with local or regional government structures.25 The state may accept this arrangement in order to keep a presence in, and a link to, the territory and the population. This means that conflict actors may coordinate—directly or indirectly—in the provision of health services. In other cases, where they do not, the consequences for civilians of receiving services from one conflict party can be dire, as actors may retaliate against them for having chosen “the other side.” For example, in areas controlled by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka during the civil war, non-state and state actors did cooperate, with the LTTE providing primary health care to the civilian population, and the government continuing to supply the hospitals and pay salaries.26 Still, the major government-run hospital in Kilinochchi remained under-resourced (fifteen doctors per one hundred fifty thousand people and with limited supplies), meaning that in the most serious cases patients had to travel to government territories for treatment.27

There is little available data on the motivations driving NSAAs’ participation in or tolerance for health care provision. However, a 2016 study on NSAAs’ perceptions of the broader concept of humanitarian action revealed positive NSAA attitudes, with members of these groups claiming that they strove to enable humanitarian access and wanted aid to be deployed in areas under their influence or control.28 It was noteworthy that the NSAAs interviewed believed that they had fewer obligations to provide aid, as compared with the obligations of the state. Finally, and importantly, many of the NSAAs reportedly explained their core rationale for facilitating humanitarian action as being one of both self-interest and concern for civilians.29 In what follows, we focus less on asking why NSAAs would respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health care in conflict settings, and instead ask why they are not doing so, given the range of benefits such provision could offer. In short, we seek to identify barriers to their provision of health care, by analyzing data from our surveys and consultations with the SDF and the AANES in Northeast Syria.

Northeast Syria comprises most of the Raqqa and Hassakeh governorates and the territory of the Deir ez-Zor governorate east of the Euphrates River. The population has been estimated at 2,400,000. This territory is controlled by the AANES as the de facto authorities, of which the SDF is the armed wing. There is also a Syrian military presence in some areas, most notably in the cities of Qamishli and Deir ez-Zor. The health system is under the control of the AANES Ministry of Health through regional health committees, except in Deir ez-Zor, where it is overseen by “a coalition of NGO workers and UN representatives.”30 The SDF takes part in the coordination of the regional health committees.31

Overall, the war has largely destroyed the health sector. In addition to deliberate attacks on health care facilities and personnel, insufficient attention has been paid to the impact of the years of conflict, human rights violations, and collapse of health systems on health and health care delivery.32 Areas under NSAA control host many of the IDPs and have fewer resources, yet also experience more significant public health problems: 55 percent of households in NES reportedly have at least one disabled member, and the lack of doctors and other specialized personnel is staggering.33 Attacks on health care facilities are currently rare, but remain an underlying threat.34 Security considerations impact access to quality health care by limiting the training of health care workers to areas under direct AANES oversight and where nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) can operate in more secure conditions (such as Al-Hasakah and Qamishli).35 Finally, the lack of coordination among humanitarian actors, local organizations, and local actors overseeing health systems (that is, the AANES) has negatively impacted population health.36

Health workers on the ground have indicated that wounded SDF members have been admitted into regular hospitals for emergency cases and have then been visited by other armed members, hence putting the nonmilitary status of hospitals at risk. The treatment of wounded ISIS fighters, who were guarded by armed SDF members, has generated related problems.37

In addition to these difficulties, political struggles between the AANES and the Syrian government makes the environment particularly challenging for humanitarian actors.38 Since January 2020, NES no longer has direct access to UN humanitarian aid, which exclusively comes from areas under the control of the Syrian government, making it dependent on the will of the government.39 Only 31 percent of medical facilities in NES are benefiting from assistance, meaning that medication is scarce and limited to simple treatments, and its access unreliable.40

Thirty-seven local health-sector organizations are operating in NES, of which the most active is the Kurdish Red Crescent (not affiliated with the International Red Cross and Red Crescent movement), in coordination with and supported by international NGOs. In the absence of a UN coordination mechanism on the ground, the so-called NES Forum oversees all health sector responses.41

Structural discrimination specifically puts the health of women and girls and people with physical disabilities at risk.42 For example, specialized medical services for women and girls are largely lacking, and are mainly limited to routine reproductive health visits and family planning. Due to the lack of skilled obstetricians and midwives, many women opt for caesarean sections. In addition, women and girls face formal and informal barriers to accessing health care, including access to female providers, who are rare. Moreover, women across Syria often need to be accompanied by their husbands or male relatives when they travel to access health services. Even female health care workers may be stopped at checkpoints and prevented from reaching patients if they are not accompanied by a male family member.43

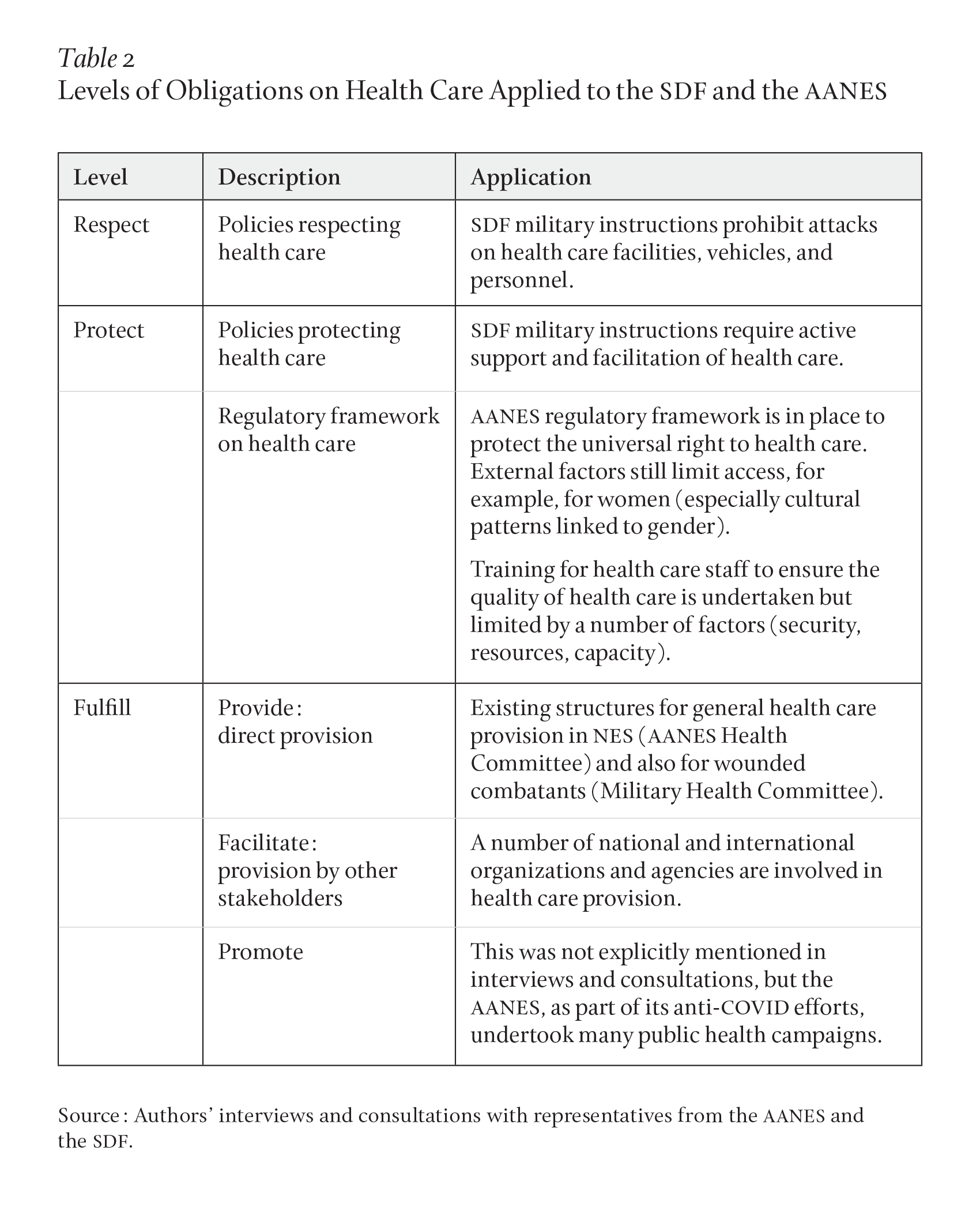

All health-service provision by the SDF/AANES is shaped by a structure that includes the SDF’s military instructions and rules, the existing regulatory framework established by the AANES, the health care committees and institutions run by the AANES, and a set of relationships with other stakeholders engaged in health care, such as local and international NGOs.

The SDF military instructions on the protection of health care, adopted in 2021, are detailed and stretch far beyond many existing NSAA policies. In addition to calling on members of the SDF to respect and protect the wounded and sick without discrimination and regardless of affiliation, and actively support and facilitate their access to health care, they call for the respect and protection of all health care personnel, facilities, and medical transports. The instructions are presented within the frameworks of international law (IHL and human rights law) and the “relevant law” of the AANES, and pledge to coordinate and cooperate with civilian authorities and relevant humanitarian and development actors.44 According to the SDF, the instructions have helped them frame their policies on health care, and they have been disseminated to all forces. In March 2021, while the instructions were being prepared, a specific incident in which the SDF entered, searched, and conducted arrests inside a hospital in Deir ez-Zor linked to ongoing military operations against ISIS reportedly proved to be a lesson learned for the SDF, and this “has not been repeated” since.45 Notably, the preamble of the instructions argues that “any incident threatening or affecting health care provision not only jeopardizes the lives of those directly concerned, but also risks negatively impacting curative, promotional, and preventative health care programmes, putting at risk the universal right to health of the population.”46

The framework that regulates the provision of health care in NES is defined and overseen by the Health Committee—established by the AANES to improve the health sector and the right to health care—and the Public Health Law. The law was drafted in coordination with “all institutions and parties working in the health sector.”47 The right to health—defined as “a physical, mental, and integral social well-being”—is integrated into the “Basic Declaration around the Rights of the NES populations to health care.”48 This echoes the SDF military instructions, of health as a universal right, belonging to the population as a whole, without prejudice or discrimination.49 The AANES Health Committee asserts that “provision of good quality health care is one of the obligations and duties of the self-administration and the achievement of this service means development, success, and acceptance of the self-administration.”50 It argues that it has the task to work toward improving living conditions for the populations of NES, of which one of the priorities is “the provision of primary health care to all people in a fair, just, and internationally acceptable manner,” free of charge.51 This requires multidisciplinary coordination among different sectors regarding health-related issues, and, as a future goal, ownership of the populations.

Concerning the provision of health care services and its current organization and structures, the Health Committee explains that health care services are provided directly to beneficiaries through health institutions, such as the nineteen existing hospitals and one hundred and ten clinics. Health care provision is regulated through a decentralized system of (local) health committees and bodies with their own administrative structures and in line with the vision of the Health Committee in NES.

Concerning health care services for persons in IDP and refugee camps, this falls under the direct supervision of the health subcommittees and bodies, and the services are “provided with the aid of some NGOs working in the camps in the NES.”52 In terms of health care for detainees and prisoners, they are “allowed decent health care in the places where they are held, and the Office of Justice and Reforms supervises the provision of health care to this category.”53 In relation to persons with physical disabilities, a section for the provision of prostheses has been set up. 54 Concerning military victims, the SDF has its own health committee, the Military Health Committee, which is responsible for providing health care to wounded combatants, from the field to rehabilitation.55

In terms of relationships with other health care actors, such as local and international NGOs, and the facilitation of the provision of health care services by these actors, the AANES explains that there are many NGOs working in the medical domain and that their work is conducted in centers belonging to the Health Committee, according to defined workplans and agreements. International NGOs train the existing medical staff to fill their knowledge gaps. There is a platform for communication with all organizations working in the medical sphere and they reportedly hold periodic meetings, supervised by the joint presidency of the Health Committee, for the discussion of all medical issues.56 The AANES sees the relationship with international NGOs (for the provision of health care services) as important as these are bridging “a gap” resulting from “the destruction of health sector infrastructure in many areas.”57 When asked how engagement with other stakeholders, such as humanitarian NGOs, could be improved, the Health Committee points to the need for improved dialogue and coordination through “channels of communication” with international organizations and agencies working in the medical domain “according to official principles meant to secure provision of health services and in accordance with official protocols.”58 More recently, the SDF has also expressed a wish for increased coordination with humanitarian NGOs on “who does what” and the existing health care needs.59

In terms of existing barriers to health care provision in this NSAA-controlled territory, the AANES Health Committee stresses the general debilitation of the health care system because of the ongoing war and the severe shortage in medical supplies, equipment, and facilities. The closure of all international border crossings, it argues, leads to the blockage of the delivery of medical and humanitarian supplies, making it very difficult “to rehabilitate health facilities and put them in action.”60 In addition, it sees the lack of financial resources and capacities as serious challenges, adding to the situation of displacement and migration of medical staff, especially doctors. These limitations mean that the AANES Health Committee can only provide for the more urgent needs. The challenge remains for grave cases, for which local solutions are not available or not sufficient. In the words of the Health Committee, “they [people] decide to go to areas outside our control like Damascus and the Kurdistan Region [of Iraq]. Of course, they face a lot of trouble in terms of access to those locations and they suffer financially, not to mention the security risks involved.”61

The health care provision and/or facilitation in NES has also been significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which accentuated the existing difficulties. The AANES report taking a number of measures (for example, the closure of all border crossings, installation of medical centers to test all people entering NES, setting up a lab running tests twenty-four hours a day, establishing quarantine centers where patients also received treatment, and imposing full lockdowns), which made NES one of the least affected areas in Syria. However, challenges remained due to limited resources and the difficulty of getting vaccines into NES.

From the perspective of the SDF, a main challenge in adhering to norms concerning the protection of health structures, they argue, is the fact that “the enemies don’t have such policies” for the respect and protection of health care. Hence, they argue, “we can become defenders of the hospitals, but then we also put them at risk. We try to evacuate [our forces] as much as we can.”62 Providing health services to wounded combatants is another serious concern for the SDF, with more than thirty thousand war-wounded, of which some cases are grave (three thousand have hindered mobility). The military hospitals dedicated to caring for these patients have limited capacity to do so. While these hospitals are performing some surgeries, there are some health issues they cannot respond to. As the SDF summarizes it: “We need either the technical means to respond here, which we don’t have, or to take them to other countries, but we don’t have this capacity,” referring to the financial, administrative, political, and other obstacles to bringing their combatants for treatment abroad.63

The above perspectives from the armed and civilian wings of an NSAA—the SDF and the AANES—enhance our understanding of how an NSAA in this particular context seeks to respect, protect, and facilitate the delivery of health care, and some of the barriers that hinder their ability to do so. We summarize these in Table 2.

In summary, and as described above, the SDF has a comprehensive policy in place to respect and protect health care. In addition, a regulatory framework concerning peoples’ right to health care without discrimination is in place in NES, through the work of the AANES. There are also local structures to organize and structure health care provision, although they are limited in the provision of many critical health care services by their capacity and resources. There are several national and international stakeholders that work on health care provision in NES—helping bridge an important gap in the service provision—with whom the AANES and SDF actively coordinate. Nevertheless, both the AANES and the SDF expressed a wish for improved coordination and communication with international organizations and agencies working in the medical domain.

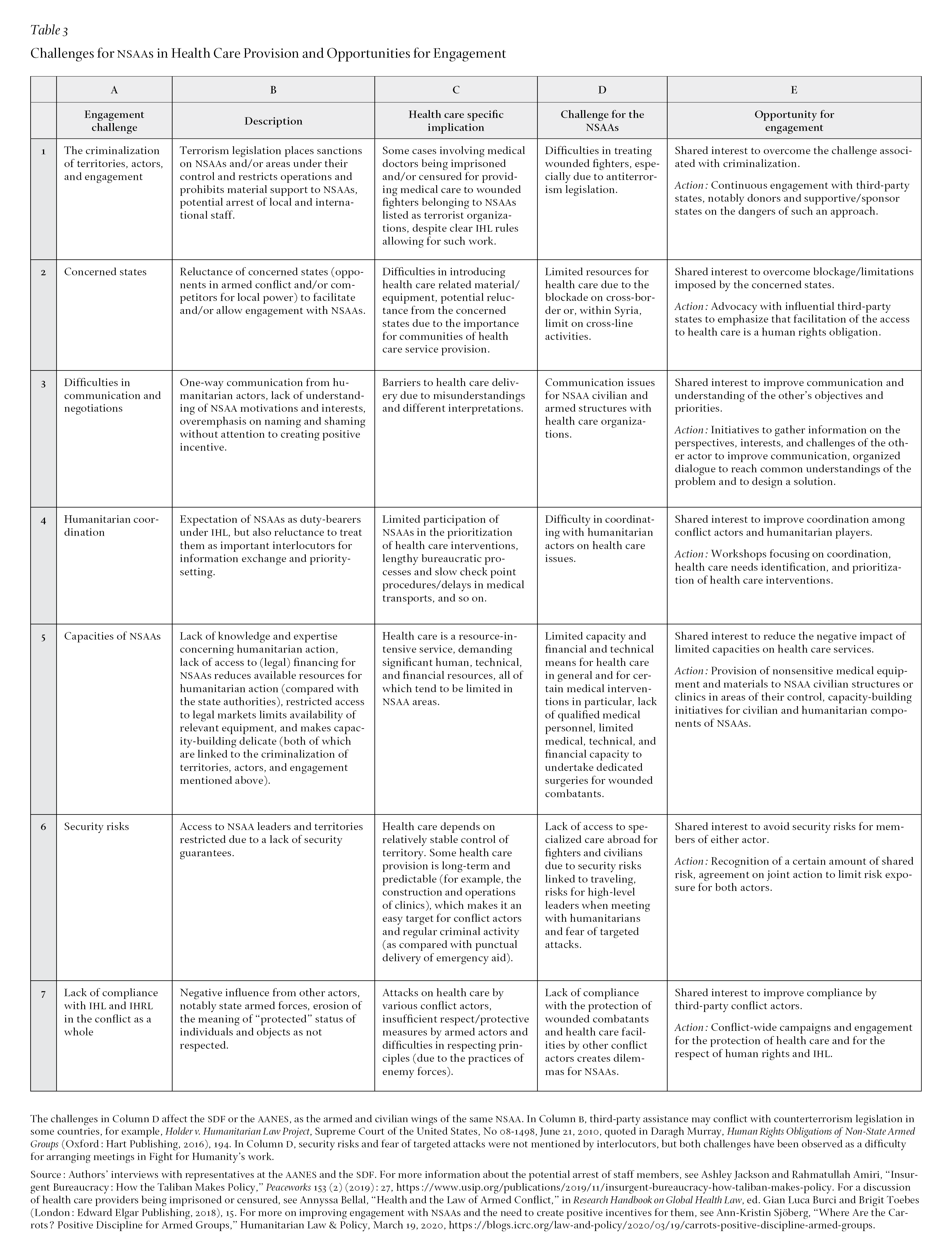

In the course of our research, the AANES and SDF identified several challenges to the provision of health care. To contextualize and interpret their views, and identify some potential opportunities, we draw on and adapt some of the existing literature—from both scholarly and policy sources—on the difficulties experienced by humanitarian actors when attempting to engage with NSAAs. Some of the key challenges featured in this literature include the “criminalization” of certain territories, actors, and humanitarian engagement, the constraints set by concerned states (meaning those involved in an armed conflict), difficulties in communication and negotiations between humanitarians and NSAAs, difficulties of coordinating with the NSAAs on needs and priorities, limited capacities of NSAAs, security risks for those involved in the engagement, and the lack of compliance with IHL by other conflict parties.64

Interestingly, as Table 3 shows, some of the challenges faced by humanitarian actors in engaging with NSAAs can also be reflected in the barriers NSAAs face when attempting to deliver health services. Column A lists challenges that have previously been identified in the literature. Column B elaborates on how these challenges affect humanitarian engagement with NSAAs, while Column C specifies how the challenges play out in the health domain. Column D then turns the challenges around to show how they manifest for NSAAs seeking to provide health care in Syria, as identified in the case study. Finally, Column E proposes opportunities for engagement between humanitarian actors and NSAAs in overcoming these challenges.

As Table 3 indicates, there is a certain coherence in some of the challenges facing humanitarians seeking to engage with NSAAs and the challenges faced by the NSAA subject to our case study. This does not mean that these are all the issues facing these two actors, but that there could be certain shared interests that, if addressed, could overcome barriers to health care provision in NSAA territory, for example, those relating to improved communication, coordination, and addressing issues linked to limited capacities and resources in these territories.

We have shown that NSAAs have been enabling the right to health care in very different settings all over the world. We have explored the efforts of one NSAA in Northeast Syria to ensure the access to health care for the population under its control, by considering its actions at all three levels of human rights obligations: respect, protect, and fulfill. The efforts of the SDF and AANES to act across the three aspects of its obligations demonstrate that NSAAs, in some contexts, can be both able and willing to meet health care obligations that extend beyond the provisions set out in IHL, despite challenging circumstances and limited resources.

We have also demonstrated that the challenges faced by the AANES and the SDF in respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the right to health care mirror challenges previously identified for humanitarian actors engaging with NSAAs, including the criminalization of certain territories, actors, and engagement, the constraints set by concerned states, difficulties in communication and negotiations between humanitarians and NSAAs, difficulties of coordinating with the NSAAs on needs and priorities, limited capacities of NSAAs, security risks, and lack of compliance with IHL by other conflict parties.

In other words, if there are shared challenges facing NSAAs and humanitarian actors seeking to deliver health care in conflict settings, there may also be opportunities to find joint solutions. To leverage this opportunity, preconceived notions about each actor—whether an NSAA or a humanitarian organization—need to be replaced with genuine efforts to communicate with and understand the objectives, perspectives, and priorities of the other. By illuminating the perspectives of one prominent NSAA on health care, we have strived to contribute to this enhanced understanding.