Expanding Representation: Reinventing Congress for the 21st Century

I. Electoral Systems: The Basics

Winner-Take-All Versus Proportional Representation

Elections are shaped by many important factors, from ballot access laws and voting procedures to campaign finance laws and candidacy requirements. As political scientists Michael Gallagher and Paul Mitchell explain, “Such rules . . . are all very important in determining the significance and legitimacy of an election. However, they should not be confused with the more narrowly defined concept of the electoral system itself.”4

Electoral systems are the methods by which votes are translated into legislative seats. While many factors determine the nature of a country’s elections, not all are “specifically about the votes-to-seats conversion process.”5

To illustrate, consider the United Kingdom’s 2024 election results, in which the Labour Party won 68 percent of seats in Parliament by securing 33.7 percent of the vote. Meanwhile, in Germany’s most recent elections, the leading parties (the Christian Democratic Union of Germany/Christian Social Union in Bavaria) won 30.02 percent of seats in the Bundestag with 30.02 percent of the vote. In the United Kingdom, Labour won seats significantly out of proportion to its share of the vote, while the leading German party’s shares of seats precisely reflected its share of the vote. The two countries use markedly different electoral systems that convert votes into seats in different ways.

Broadly, electoral systems can be divided into one of two classes: they are either winner-take-all or proportional.6

In winner-take-all electoral systems, the election winner secures 100 percent of the available seats, regardless of the actual share of the vote received. A winner can be established either on a majority basis (meaning that the winner must receive 50 percent of the votes plus one) or a plurality basis (meaning that the winner simply receives the most votes, even if that amount is less than 50 percent of the total number of votes cast). Winner-take-all systems may use either single- or multimember districts, though single-member districts are more common. In the United States, each congressional district is represented by a single official, so if that candidate wins 50 percent plus one vote (or if the winner can be established by a plurality), they in effect win 100 percent of the seats. Voters who did not back the single winning candidate do not have an official representing them for whom they voted. Winner-take-all is used in all U.S. state and federal legislative elections and most municipal elections. It is also used in a few other major democracies, including the United Kingdom, Canada, and India.

In contrast, proportional systems aim to ensure that a group’s share of seats reflects its share of votes.7 For instance, if a given multimember district has six seats, and a party secures 50 percent of the vote, the party’s candidates will win three of those seats. Proportional systems can exist only in multimember contexts, but they come in a rich diversity of forms; and while common variants exist, no two countries’ systems look exactly alike. Nonetheless, they all share the property of aiming to roughly approximate seats to votes.8 It is the most common electoral system among the world’s democracies today.9

To illustrate the system in practice, consider Illinois. Like all states, Illinois uses winner-take-all to elect its congressional delegation. In the 2024 election for the U.S. House, nearly 53 percent of the state voted Democratic, yet Democrats won fourteen of the seventeen available seats. That is, 53 percent of the vote translated into 82 percent of the seats. Meanwhile, Republicans, who commanded 47 percent of the vote, secured only 18 percent of the seats. In Illinois, Republicans do not constitute a majority in most districts and so Democrats are likely to win the single seat available in most cases. The cumulative effect is a lopsided delegation in Congress.

Consider how outcomes would likely change under a proportional system instead. Illinois could create, say, four three-member districts and one five-member district. With districts featuring at least three seats, Republicans—who regularly constitute roughly one-third or more in nearly all of today’s single-member districts—would secure at least one in each, significantly lessening the gap between their share of the vote and their share of seats.

Why Does Federal Law Require Single-Member Districts?

Today, federal law mandates that all states use single-member congressional districts, although some states still use multimember districts for state legislative races.10

Since the nation’s founding, many states have used multimember districts in the form of statewide at-large voting, also known as bloc voting, a type of winner-take-all system. Instead of allocating multiple winners proportionally to votes, winners were determined by a plurality or majority. In practice, this meant a single majority group could elect every seat in the state. The system was used to deny fair representation both to partisan and racial minority groups. As a result, multiple Congresses in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries passed laws prohibiting the system and instead requiring the use of single-member districts—another variant of winner-take-all, though a less evidently nonproportional one. The latest mandate was passed in 1967 to improve representation for African Americans during the burst of legislative activities that attended the Civil Rights Movement.11

The reform examined by this paper is fundamentally different from systems used earlier in our country’s history. We recommend that multimember districts be used with a proportional allocation of winners: in effect, the exact opposite of the methods previously used to exclude all groups except the majority faction.12

While we highlight here an example in which winner-take-all disfavors Republicans, the consequences can affect any political party. As we explore in greater depth below, the consequences are also felt beyond partisanship: gender, racial, and ethnic groups, issue-based constituencies, and other groupings of voters that typically fail to constitute an outright majority in any given jurisdiction regularly struggle to secure representation commensurate with their numbers under winner-take-all.

The American colonies inherited winner-take-all from the United Kingdom. Various framers imagined a House that would proportionally reflect the electorate; but proportional systems had yet to be developed. As political theorist Robert Dahl observes, winner-take-all was “the only game in town in 1787 and for some generations thereafter. The Framers simply left the whole matter to the states and Congress, both of which supported the only system they knew.”13 Later, Congress passed a law mandating single-member districts for House elections, thus cementing winner-take-all as the rule for federal races.

Where Are Multimember Districts Currently In Use in the United States Today?

Multimember districts can be used in both proportional and winner-take-all electoral systems. When combined with a proportional method for allocating winners, multimember districts generate a proportional electoral system; when used with a plurality or majority allocation, they generate a winner-take-all system. Multimember districts are currently used in both forms across various U.S. jurisdictions today.

In the form of proportional representation, multimember districts are used in some cities—such as Portland, Oregon, and Cambridge, Massachusetts—although no states use a proportional system for state legislative or congressional elections.14 More than one hundred additional cities use systems considered semiproportional.15 These were typically adopted in response to lawsuits brought under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. This paper does not examine semiproportional systems. Instead it focuses on methods we consider to be more fully proportional, although semiproportional systems have been successful at mitigating vote dilution in municipalities.

Ten states use multimember districts for state legislative elections, but none combines it with a proportional allocation of winners.16 This kind of system, termed bloc voting, is a distinctly nonproportional variant of winner-take-all in which multiple seats are typically allocated to the majority group rather than allocated proportionally. Because of its potential to suppress, rather than enhance, representation of minority groups, bloc voting for congressional elections is fundamentally at odds with the recommendations outlined in OCP.

Public Support for Reform

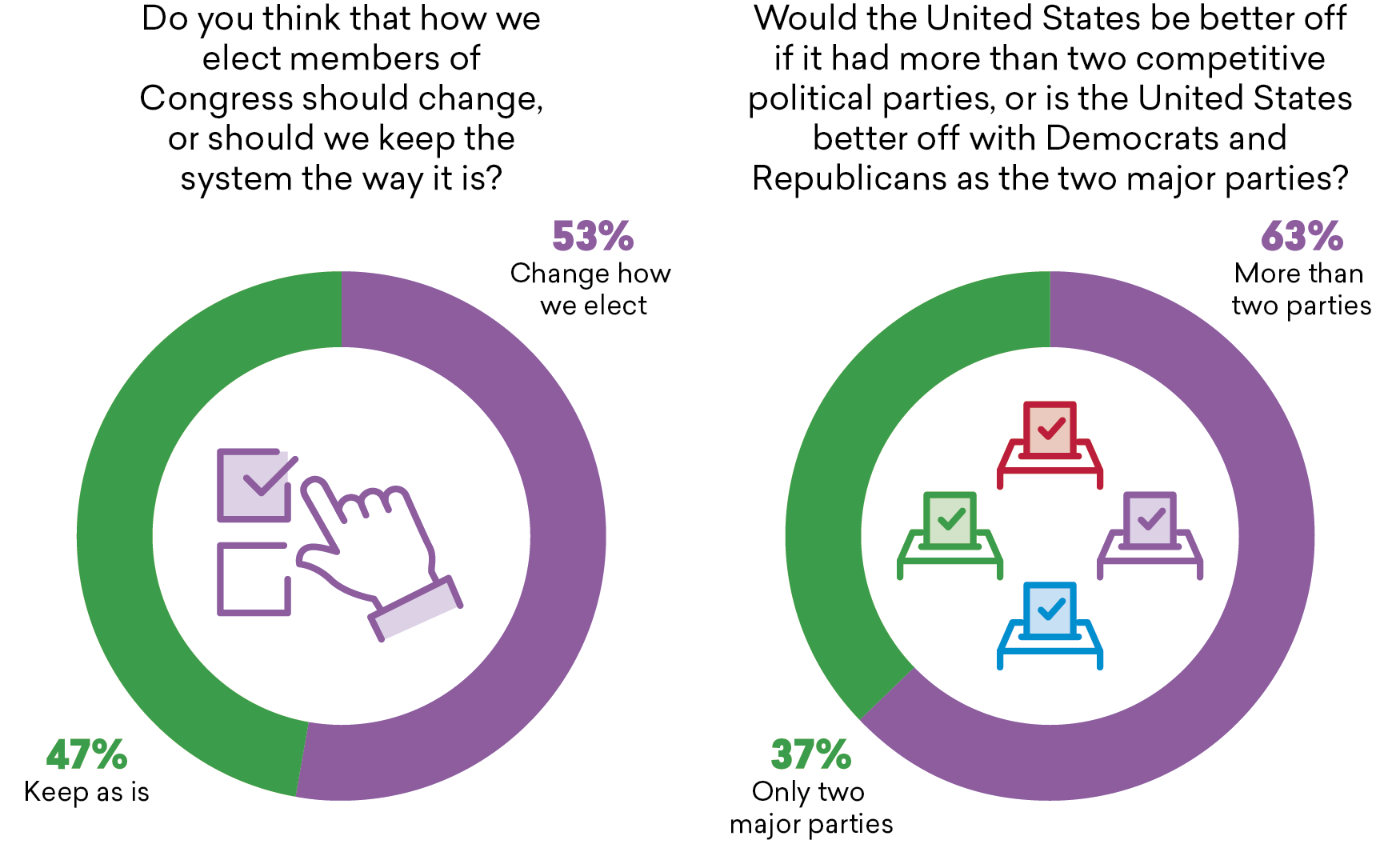

In September 2024, the Academy commissioned a public opinion research exercise to assess potential support for electoral reform. The exercise included a large-scale survey of 3,200 eligible voters complemented by focus groups. Across partisan lines, respondents demonstrated significant distrust of the federal government: 78 percent said government in Washington can be trusted only some or none of the time, including 69 percent and 63 percent of Democratic women and men, respectively, and 89 percent and 86 percent of Republican women and men, respectively. In turn, 53 percent support changing the system by which Americans generally elect their lawmakers.

Public understanding of electoral systems and reforms like proportional representation is understandably limited. However, respondents were more compelled by the idea of generating additional political parties than by reform in general, with 63 percent supporting changes that would permit more than two options (including 63 percent among Democrats, 80 percent among Independents, and 58 percent among Republicans). Further, when framed as generating additional parties, increased support for reform was most pronounced among those who were otherwise most skeptical of change in general, including Republican men, voters without a college degree, and voters who pay little attention to politics. (The lowest level of support for more than two parties, 49 percent, was among those without a college degree.) Finally, results indicate majority support (60 percent) for adding 150 new members to Congress when that change is framed in a way that emphasizes its potential to help representatives better understand their constituents’ needs.

Americans are open to changing our electoral system

In general, discussing the mechanics of electoral system design—as does the analysis that follows—is far less compelling than the potential outcomes, such as reducing corruption, reducing the power of interest groups, and improving the competence of and voter communication with lawmakers.

Policymaker Interviews

To better understand the political opportunities and barriers to moving toward proportional representation, the working group and Academy staff conducted several interviews with policymakers and advocates at the federal, state, and local levels. Legislators currently working on electoral reform noted that they were motivated to do so because of its potential to reduce polarization, improve representation, and eliminate “spoiler” effects and other idiosyncrasies of our current winner-take-all system. They cited inertia as the most significant barrier to electoral system change; current elected leaders have done well under the existing winner-take-all system and thus are reluctant to change it. One legislator suggested that overcoming this barrier may require setting legislation to take effect far in the future to allow a long adjustment period.

Some policymakers also expressed concern about whether changes would provide advantages to the opposing party and whether voters would understand and support a new electoral system. One policymaker noted the existence of certain “sacred seats”—majority-minority districts that were formerly represented by historically significant figures, giving them a resonance and importance beyond the seat itself. Because moving to multimember districts would effectively dismantle these districts, voters within those districts may have particular reason to view any changes as a step back from hard-fought gains for underrepresented communities.

Among community leaders familiar with successful local efforts to adopt STV, one of the most important benefits reported was the ability to form new coalitions. These coalitions could include established representatives and voters or community members new to electoral politics. In other cases, community leaders found that the ability to discuss and address policy concerns that impacted many voters but were not usually part of elections, such as the performance of municipal services, generated the most excitement.

Finally, in our interviews, we encountered situations in which ranked-choice voting and STV were treated as interchangeable or assumed to have identical features and effects—even where the evidence does not point to these conclusions. This underscores the importance of ensuring that public discussion clearly delineates the differences between single-seat ranked-choice voting and the OCP recommendation discussed here.

Single-Winner Versus Proportional Ranked-Choice Voting

Our Common Purpose recommends two versions of ranked-choice voting: a single-winner version, which is the focus of Recommendation 1.2, and a multiseat, proportional version, which is the focus of Recommendation 1.3. In both versions, voters rank the candidates in order of preference. Differences arise with the number of seats filled via the election.

In the single-winner version of ranked-choice voting (RCV, also called “instant-runoff voting”), if a candidate wins an outright majority of first-choice votes, the race is over, and the candidate secures the seat. However, if no candidate has a majority of first-choice votes, then the candidate with the fewest first-place votes is eliminated, and ballots that had indicated a first preference for the eliminated candidate are allocated according to their second choices. This process continues until a candidate has more than 50 percent support.

Winner-take-all systems may have either a plurality or majority requirement for winning a seat, with the latter typically requiring a run-off between the final two candidates to generate a majority winner. Single-winner RCV operationalizes a majority winner requirement through an alternative to a multi-election run-off. A majority requirement—whether achieved through run-offs or RCV—helps avoid “spoilers” (nonwinning candidates whose presence on the ballot changes which candidate wins the election) and ensures that the winner has support from a majority of the voters. In addition, the need to appeal to other candidates’ supporters to get their second-choice votes may potentially reduce negative campaigning and/or drive candidates to moderate their policy positions.

However, in any single-winner race—even one with a majority requirement—large numbers of voters (potentially nearly 50 percent) can still be stuck without a representative of whom they approve.

RCV can also be implemented with multiple-winner rules. This system is generally known as either single transferable vote or proportional RCV. A win threshold is established based on the number of seats available. That threshold will be lower than the 50 percent required to win a seat in the single-winner version of RCV. For instance, in a three-seat district, a candidate will need 25 percent plus one vote to win. As in the single-winner version, voters rank the candidates on their ballot. When a candidate surpasses the win threshold, the surplus votes are allocated to the candidate’s supporters’ second choices according to a formula. Whenever no candidate reaches the threshold, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and their supporters’ votes are transferred to their second-choice candidate. This process continues until all the seats are filled.

In short, in multiseat districts, election results will deliver seats to a broader range of parties, factions, or identity groups roughly in line with the amount of relative support they have from voters.