Expanding Representation: Reinventing Congress for the 21st Century

Executive Summary

Across partisan lines, Americans today are deeply dissatisfied with our political system:

- 80 percent say that public officials do not care much about what people like them think;

- 70 percent say that half or more of the people running the government are corrupt;

- 69 percent say that people like them have no say in what the government does; and

- 78 percent say either that the government in Washington can be trusted only some of the time or that it cannot be trusted at all.1

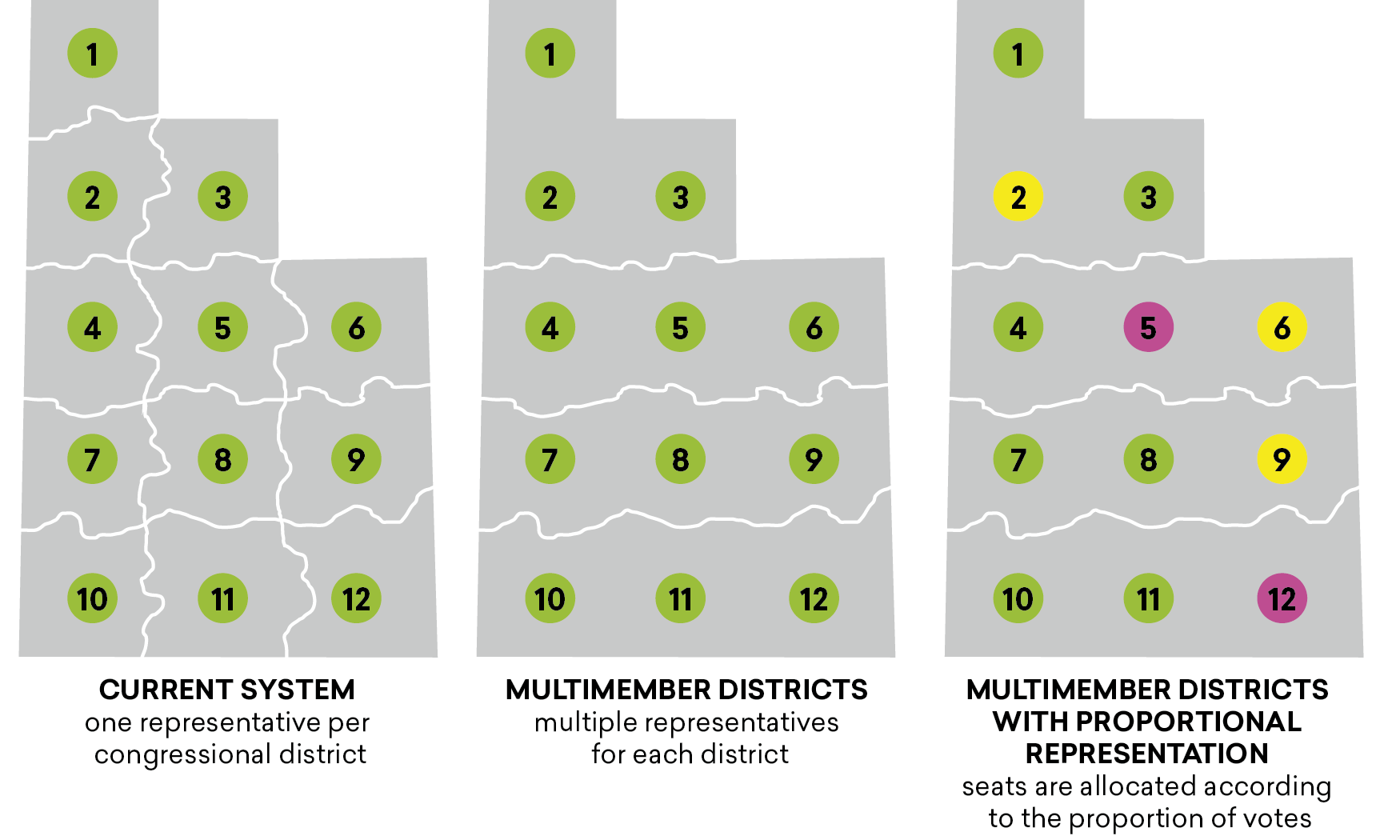

Faced with this deepening voter frustration, a growing number of scholars and advocates have encouraged policymakers to consider America’s electoral system, or the system by which votes are translated into congressional seats, as one important source of dysfunction. In our current winner-take-all electoral system, one candidate is elected per district, and the person who receives more votes than any opponent wins that sole available seat (that is, “takes all”). Winner-take-all systems can leave large portions of the electorate—up to nearly 50 percent in very close elections—without a representative who shares their views. Researchers have linked this type of system to a variety of negative outcomes, including a decrease in competitive legislative races, the underrepresentation of women and racial and ethnic minorities, and escalating polarization and extremism.

As part of its groundbreaking 2020 report on reinvigorating democratic citizenship, Our Common Purpose: Reinventing American Democracy for the 21st Century, the Commission on the Practice of Democratic Citizenship recommended moving from our current winner-take-all structure to a system known as single transferable vote (STV; sometimes also called proportional ranked-choice voting or emergent proportionality) to elect members of the House of Representatives.2 This is a type of proportional representation, or a system in which multiple representatives instead of one are elected from each district and seats are won in proportion to votes.

This paper is intended to help policymakers and reformers better understand this Our Common Purpose recommendation, as well as a broader array of proportional options. It is the product of a working group of political scientists, legal scholars, advocates, and others convened by the Academy who offered their diverse expertise as a complement to the extensive scholarly literature on the topic. The paper does the following:

- Provides a primer on electoral systems, including the key distinctions between the two main classes: winner-take-all, currently used for most U.S. federal, state, and local elections, and proportional representation.

- Reviews the core components of any electoral system, with recommendations on basic design decisions when considering proportional systems in the United States. These components include district magnitude, assembly size, ballot structure, and allocation method.

- Distills existing scholarship to suggest how changes to our electoral system could affect the health of American democracy. While the impacts of any change are not guaranteed, shifting away from a winner-take-all system as outlined here is associated with improvements that are vital to America’s civic health, including reducing negative polarization, increasing voter turnout, and increasing representation across several kinds of group characteristics. International experience shows that proportional representation is also associated with stable governing and lawmakers advancing policies that broadly serve the electorate.

The paper intends to be an accessible resource for understanding what proportional representation is, how it might be designed for U.S. elections, and why it should be considered as a potentially powerful reform given the existing and growing evidence of its impact.

Multimember Districts with Proportional Representation