Preparing Students for Civic Life: A Guide for Higher Education Leaders

Strategies for Embedding the Practice of Democratic Citizenship Throughout Institutional Culture and Curriculum

- Facilitate cross-campus collaboration on democratic engagement.

- Foster student civic engagement beyond election years.

- Engage every major with civics.

- Empower faculty to cultivate civic skills and incorporate civic knowledge into their curricula.

- Foster skills in discussion and listening.

- Articulate the value of democratic engagement for students and parents.

- Engage local communities to create opportunities for the practice of democratic citizenship.

- Identify key performance indicators to measure political learning.

1. Facilitate cross-campus collaboration on democratic engagement.

The work of instilling democratic values across a higher education institution should not be assigned to a single department, office, or student group. After all, student leaders graduate, administrators leave, and funding can dry up. Instead, campus leaders should aspire to cultivate a culture of democratic participation that will enable larger structural change. To build this culture, campus leaders need to promote collaborative efforts that touch all parts of university life.

One place to begin this effort is by making democratic citizenship explicit in the institution’s mission statement and across curricula, extracurricular programming, and faculty-development efforts. Leaders should identify a broad coalition of campus stakeholders already eager to do this work and deputize them to spearhead specific efforts. President’s offices can serve as central hubs for distinct democratic workstreams. University leaders can leverage their unique bird’s-eye view of campus—as well as their discretionary funding and cross-campus convening and communications power—to ensure collaboration between prodemocracy efforts.

See Trevor Brown, “Leveraging Mission and Traditions to Prepare Democratic Citizens,” case study from The Ohio State University.

2. Foster student civic engagement beyond election years.

Voting represents just one of many ways students can exercise civic skills and civic knowledge. Voter turnout should be considered the floor, not the ceiling, of democratic engagement on campus.

To foster sustained civic engagement, campuses need to facilitate civic opportunities for students. Schools should make it as easy as possible for students to engage with local government, to learn more about decisions that affect them personally, and to build connections with others who are passionate about similar issues. These efforts can be accomplished by, for example, bringing lawmakers to campus or offering students paid opportunities to get involved. Students live busy lives, and university leaders can reduce barriers standing between young people and a more active democratic engagement, especially during nonelection years.

See Josh Blakely, “Making a Whole-Campus Commitment to Citizenship,” case study from Longwood University.

3. Engage every major with civics.

Students’ ability to select their own areas of study presents a potential challenge for an institution seeking to instill democratic values. Some students, after all, may—even unintentionally—avoid courses focused on civic knowledge or avoid departments in which civic skills are a key part of how classrooms are managed. According to data from Tufts University’s National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement, students that major in STEM fields historically have lower rates of democratic engagement, including voter turnout.13

It does not have to be this way. A whole-campus commitment to democracy means creating opportunities for every classroom to instill civics in a subject-matter-relevant and nonpartisan way—even in classes focused on topics that, on the surface, are not connected to democracy. One step institutions can take to improve civic participation among all majors is to establish civics courses as part of the required curriculum. Civics can also be incorporated into existing course material across a wide range of fields. To further engage STEM majors, campuses can provide programming that connects democratic participation to issues these students are passionate about.

See Josiah Ober, “Civics and Campus Life,” case study from Stanford University.

4. Empower faculty to cultivate civic skills and incorporate civic knowledge into their curricula.

Every classroom should embody the principles of free expression, open inquiry, and civil disagreement. Faculty members, particularly in fields that may seem distant from democratic issues, have a unique opportunity to bolster students’ civic knowledge and civic skills. However, faculty may be loath to take up such programming on their own. Faculty are fearful of slipping into partisanship or igniting controversy. Many faculty members see their role as limited to their specific subject. Or they may simply feel that they lack the expertise to facilitate conversations about civic topics. Institutions’ cross-campus collaborative efforts on democracy would provide the justification and the impetus for professors to incorporate civic knowledge into their course materials.

Even more important, university leaders need to arrange pedagogical training for faculty. These trainings should emphasize the disposition of curiosity and should help faculty become more comfortable raising—and soliciting—both un-popular opinions and conversations related to democratic life. Institutions should have a comprehensive centralized resource for training faculty in this area.

See Sarah Surak, “Teaching Faculty How to Incorporate Civic Engagement into Their Curricula,” case study from Salisbury University.

5. Foster skills in discussion and listening.

Americans need to get better at talking to one another. Young people—and college students—are no exception. One-third of college students are uncomfortable sharing their political views on campus, according to an Institute of Politics study, while a study by the Constructive Dialogue Institute and More in Common found 45 percent of students, and 64 percent of very conservative students, regularly hold back opinions to avoid upsetting their peers.14 If students self-censor, they impoverish their education and leave themselves—and their peers—unprepared for a political system that depends on give-and-take.

In response to increasing polarization and division, institutions of higher education must do more to encourage engagement with a broad diversity of viewpoints. They also need to build students’ competencies in civil discourse, constructive debate, and mutual understanding. Such competencies cannot be taken for granted. Students need to learn how to listen to one another, make evidence-based arguments, and discuss hard issues. Learning to do so in the classroom will help them have these conversations in their dorms, dining halls, and other parts of campus. Universities should ensure that students have access to spaces where they are exposed to divergent viewpoints, where they can learn to respect those perspectives, and where they can come to recognize the value of compromise.

See Brian Dille and Deanna Villanueva-Saucedo, “Workforce Development and Civic Education,” case study from Maricopa County Community College District.

6. Articulate the value of democratic engagement for students and parents.

An education that prioritizes democratic participation does not just serve society at large. Students themselves benefit in the form of improved life satisfaction, stronger relationships, and better job opportunities. However, such benefits are not necessarily self-evident. Many students attend college on the expectation that what they learn will help them in their career. Many parents send their children to college expecting that their degree will provide a boost in the labor market. Leaders should make a point of articulating what students gain when they learn how to embody democratic values. Conversely, understanding the ways business and private enterprise rely on democratic governance and the rule of law will better equip students to understand both constitutional democracy and any future professional pursuits. Regardless of professional field, employers want workers who know how to listen, can think critically, and can empathize with different viewpoints. Explaining these facts at the outset will motivate students to prioritize developing civic skills and civic knowledge.

See Brian Dille and Deanna Villanueva-Saucedo, “Workforce Development and Civic Education,” case study from Maricopa County Community College District.

7. Engage local communities to create opportunities for the practice of democratic citizenship.

Research has shown that participating in one’s community and working with others on an issue has a lasting impact, including improved social-emotional well-being.15 If students build muscles of involvement with democratic practice when they are young, they may be more inclined to engage in these efforts as they mature. Institutions, then, should provide opportunities for students to improve both their knowledge of local government and their direct engagement with it.

See Marianne Wanamaker, “How Higher Education Institutions Can Engage Students with Local Government,” case study from University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

8. Identify key performance indicators to measure political learning.

Making a whole-campus commitment to democracy is one thing. Measuring that commitment and gathering data on the effectiveness of that commitment represent additional challenges. Ideally, institutions should measure two trends. First, they should assess the degree to which their campuses encourage students to be responsible citizens. How many academic departments or courses have incorporated civics into their curricula? How many on-campus bodies have hosted democracy-adjacent programming? What extracurricular opportunities are available that help students get involved with their local community? Second, institutions should measure students’ engagement with these efforts by tracking course enrollment, extracurricular participation, and improvements in students’ civic knowledge and civic skills.

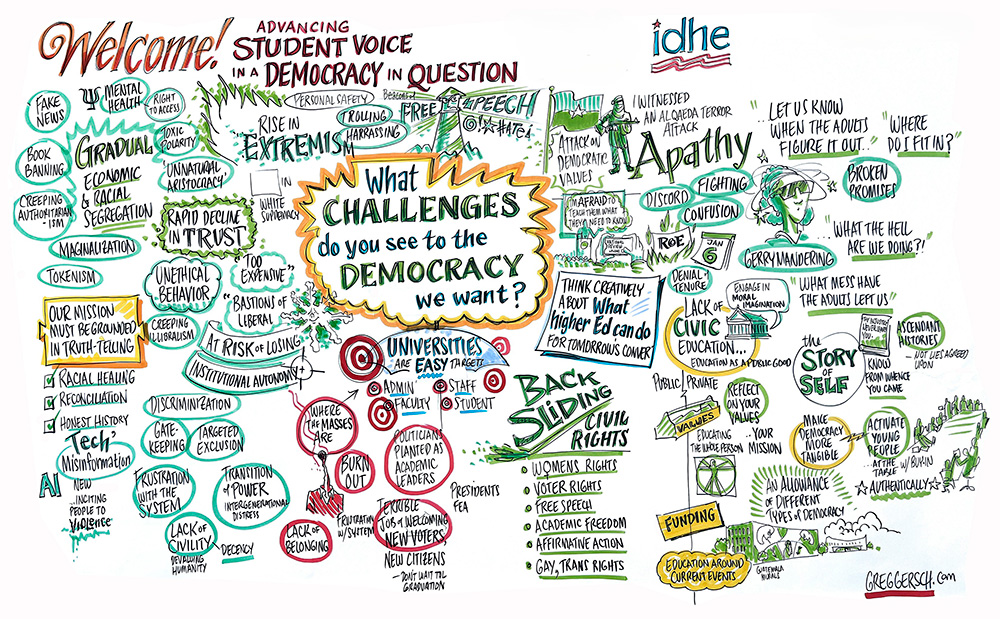

Capturing metrics such as these is always difficult. University leaders can draw inspiration from an initiative of the Institute for Democracy and Higher Education (IDHE), a nonpartisan applied research and resource center housed within the American Association of Colleges and Universities. Over the past decade, IDHE has completed twenty-five qualitative campus climate studies to examine the attributes of highly politically engaged campuses. These campuses were “outliers” in the sense that their aggregate (institutional) student voting rate was significantly higher (and, in a few cases, significantly lower) than IDHE predicted based on a statistical model they created. Four of the twenty-five campuses were selected because they had closed equity gaps in voting, based on IDHE’s statistical modeling.16

Based on this research, IDHE found that students learn about democracy primarily through the campus climate for political learning and participation, rather than from any single program or department. IDHE identified a few important questions to evaluate through focus groups, surveys, and other mechanisms, all of which represent the kinds of institutional norms, symbols, structures, and behaviors university leaders should endeavor to measure on their campuses:17Are skilled political discussions pervasive across campus? Are students educated to become leaders, community organizers, activists, and agents of social change? During elections, do campuses not only remove barriers to student voting but turn the election season into opportunities to learn about democracy and their responsibilities in a governing system “of, by, and for” the people? Finally, how pervasive are norms of caring and of shared responsibility across the campus community?

Of course, focus groups represent just one of many approaches to gathering data on democratic engagement. Campuses could consider conducting a civic assessment survey for first-year students and then readministering the survey when students graduate.18 Importantly, individual institutions need not create a new measurement tool from scratch. Existing options like the Institute for Citizens and Scholars’ civic readiness map offer ready-made measurements available for higher education leaders.19