The Case for Enlarging the House of Representatives

Part II: The House and Representative Democracy

How big should a legislative assembly be? As our nation’s founders understood, there is no obvious answer. As a general rule, assembly size offers a trade-off between efficiency and representativeness: The smaller the assembly, the more efficiently it can function. But the larger the assembly, the more representative it can be.17

At the state level, assembly size varies considerably across the nation. Tiny New Hampshire has 400 representatives in its lower chamber, while California, the most populous state, has just 80. Assembly size also varies considerably between countries, though it largely follows a consistent pattern (see International Comparisons).18

Before exploring specifics about chamber size, we might ask a more fundamental question: what is the purpose of a representative legislative assembly? The standard answer is straightforward. Self-governance requires a legitimate lawmaking body. Since it is impractical (and almost certainly undesirable) for every citizen to participate directly in governmental decision-making, a representative assembly offers a means to aggregate the perspectives and interests of a larger society into a single lawmaking body. This body should make laws in a broadly conceived “public interest,” or should at the very least help people feel like they have a voice in the rules that govern them.

Since citizens participate in government through periodic elections, participatory processes, and lobbying, the elected representative becomes the main link between citizens and their government. As a result, the question of representation has long been central to scholars of democracy. The debate dates back to eighteenth-century philosopher Edmund Burke’s distinction between the “delegate” and “trustee” models of representation. In the delegate model, representatives are mere stand-ins for constituency opinion and should act directly on behalf of their constituents. In the trustee model, representatives are elected for their character and judgment. To this day, contemporary political theory is full of debates over competing ways to conceptualize representation.19

On a broader level, a representative assembly can also be considered crucial for national cohesion. In this conception, a legislature is much more than the sum of its individual members. Instead, it is the one and only grouping that is truly representative of the entire nation, and the one and only venue in which individuals with perspectives across the ideological and geographic spectrum engage and deliberate with each other. In the process, legislative assemblies help forge the identity of a larger nation. If no one perspective has a monopoly on the truth, and if all perspectives can find themselves somewhere in a national legislature, then the idea of representation is something transformative. Congress becomes more than just a lawmaking body. It becomes a forum that helps Americans see the diversity of the country and that this diversity comes together to build something greater than the sum of its parts.20

There may be no one perfect way to represent a larger group of citizens. But any form of representation must involve at least some fealty to the values and interests of the citizens who are represented. And the larger the representative body, the more likely it is able to reflect the nation as a whole.

The Bigger the District, the Weaker the Electoral Connection

The standard account of representation in the U.S. Congress is that because members of Congress want to be reelected, they work hard to maintain a constant connection to their constituents.21 They show up at community events, hold town halls, and speak to community leaders. Some of these practices amount to little more than campaign stops, some are genuine attempts to connect with constituents. Regardless of representatives’ intentions, these appearances can serve a positive function. By trying to maintain a constant presence in front of their voters, representatives hear from their constituents and get a sense of what their concerns are.

However, there can be no guarantee that the constituents who representatives see are typical of their voter base. In a political science classic, “Constituency Influence in Congress,” Warren Miller and Donald Stokes write:

The Representative knows his constituents mostly from dealing with people who do write letters, who will attend meetings, who have an interest in his legislative stands. As a result, his sample of contacts with a constituency of several hundred thousand people is heavily biased: even the contacts he apparently makes at random are likely to be with people who grossly overrepresent the degree of political information and interest in the constituency as a whole.22

Or as political scientist Richard Fenno put it in another classic phrasing, “the constituency that a representative reacts to is the constituency that he or she sees.”23 Even in the Internet age, representatives are influenced most by the voters who best make themselves seen and heard.

As a general rule, representatives want to represent their constituencies. But how they define and see their constituency depends very much on which constituencies they actually see, and which constituencies they most fear upsetting.24 The more constituents a member represents, the more abstract the constituency becomes to them. Someone who represents one hundred people can know and understand the people she is representing very well. A representative for one hundred thousand voters has a more diffuse picture, likely distorted by those who make the most effort to be seen. A representative who represents one million people has an even more diffuse and distorted picture.

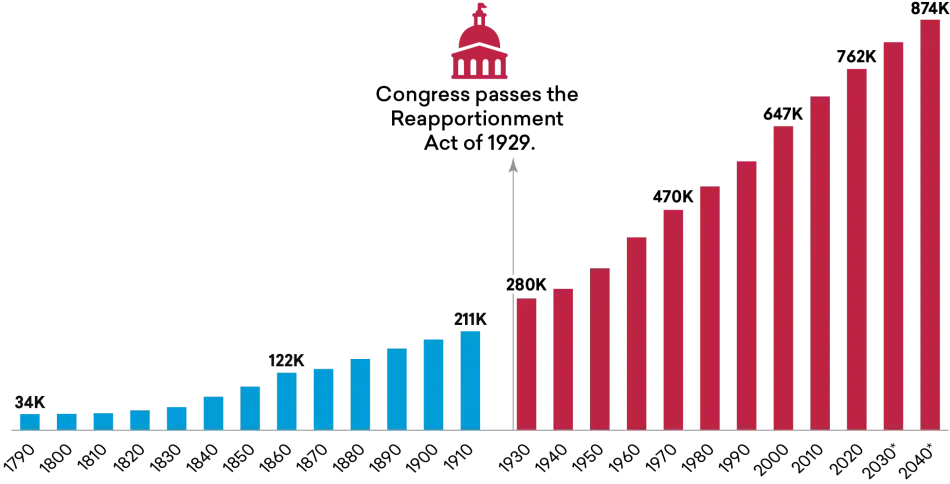

Figure 1

Average House District Size, 1790–2040

Note: Dates with an asterisk are projected.

In the twenty-first century, it is both easier and harder for members to understand their constituency and what it wants. There is far more high-quality polling available (at least theoretically high quality), and members are responsive to such polling.25 But it is also easier for small groups to organize and flood offices with calls and emails and social media engagements, thus creating an unrepresentative picture of the constituency. Indeed, this distorted view is increasingly becoming the reality, as sophisticated grassroots lobbying organizations are adept at making themselves seem larger and more influential than they really are.26

It is possible, even likely, that a representative of one hundred thousand people could present herself before a decent percentage of her constituents over the course of several terms. Likewise, these constituents could get a sense of who their representative really is and feel like they know her. However, the likelihood that citizens will be able to assess their representative directly declines as district size increases. Instead, they are left to evaluate their representatives more indirectly: through partisan affiliation, campaign advertising, media coverage, and other stand-ins. In a world of limited resources, representatives prioritize services for the constituents they consider most important to them and their chances of reelection.27

Numerous studies have found that the bigger the state, the less likely citizens are to have direct contact with their senators and the more likely they are to consider their senators as unhelpful.28 Though there is less variation in House district size, political scientist Brian Frederick found in a 2008 study that the smaller the district size, the more likely citizens were to have contact with their representatives, the more likely citizens were to reach out to representatives for help, the more likely they were to feel like their representatives did a good job keeping in touch with the district, and the more likely citizens were to approve of their representative. As Frederick concludes, “it becomes progressively more challenging” for citizens to gain access to a representative “as the number of citizens each representative serves rises, and voters appear to notice. There is a measurable cost to allowing an unchecked district constituency population growth.”29 One Spokane, Washington, resident told the American Academy’s Commission on the Practice of Democratic Citizenship: “[The] country keeps growing with its population and so it’s a lot harder to get the attention of your congressional representative now than it apparently used to be, way before any of us were born.”30

Critics may contend that, even with smaller districts, representatives would focus on only their loudest constituents. It is unlikely the House would be expanded to the point at which any district would have fewer than 200,000 or 300,000 residents, so there is no hope of returning to a full-on retail-politics style arrangement that was possible early in the nation’s history. However, there is a meaningful difference between a voter who is 1 of 700,000 or even one million and a voter who is 1 of 400,000 or 500,000, particularly in the arena of constituent services. Constituents frequently make requests of their representative’s office, which is also charged with making sure voters feel their voice is heard. According to the Congressional Management Foundation, Congress receives between twenty-five million and thirty-five million messages a year from the American people, an average of between 46,000 and 65,000 per congressional and Senate office.31 Any reduction in district size—without a corresponding decrease in the funding of congressional staff—would increase the chamber’s capacity to respond to these requests and let the American people feel they are being well—or at least better—represented.

As Our Common Purpose explains, part of the crisis of American democracy today is a crisis of trust in government. Building a closer connection between individual citizens and their representatives could be a significant step toward restoring some of that trust.

Expanding the Talent Pool of Representatives

District size also affects who runs for office. An obvious advantage of enlarging the House is that the regular addition of new districts would create open seats, offering opportunities for a new generation to serve in Congress. At the very least, an expansion of the House would be the quickest way to make Congress more diverse without resorting to term or age limits. Smaller districts do more than create opportunities for more people to serve in Congress. They lower the obstacles to run for Congress in the first place.

Running for Congress is a big deal. Campaigning and fundraising pose barriers and put tremendous demands on candidates. Anyone running for Congress who does not have access to significant fundraising resources is discouraged from launching a campaign. This privileges wealthier candidates and especially candidates who have access to networks of wealthy potential donors. It also privileges candidates who have strong ideological and partisan commitments that can keep them motivated through the long, uncertain slog of campaigning.32

Smaller districts, then, can help make running for office more accessible to a more diverse talent pool. Smaller districts help reduce the personal costs of running for office (less fundraising, fewer voters to reach out to) and create more opportunities for parties to recruit more diverse candidates. This can help candidates who might otherwise be deterred from running for office given the relatively few opportunities and the higher personal cost required under the current size of House districts.33

Voter Influence

For voters, the larger the district size, the less important any single voter is in deciding the election. To put it another way, the probability of any individual casting the deciding vote decreases as the number of voters increases. To put it a third way, in a larger district, representatives can afford to ignore more voters.

As districts become larger, they tend to become more heterogeneous. On the one hand, this flattens out the diversity of representation, making it harder for more extreme candidates to win. On the other hand, it also makes it harder for more idiosyncratic candidates and diverse candidates to win, as they may have a naturally more limited base of support. It also makes it harder for particular constituencies to elect their candidates of choice unless they are intentionally drawn into districts for the sole purpose of electing certain types of representatives. This is the theory behind majority-minority districts: without districts drawn specifically to ensure racial minority representation, minority candidates could be unlikely to win elections (though recent years have seen a growing trend of minority members elected from non-majority-minority districts). However, racial minority representation is a unique case. There are no districts drawn, for example, to ensure representation of lower-income voters. And few predominately nonwhite neighborhoods are located in areas that are sufficiently self-segregated to have even a chance at becoming a majority-minority district. Similarly, given the size of districts today, many rural areas are not populous enough to form distinct districts. As a result, rural areas are occasionally drawn into the same district as suburban or urban neighborhoods, often resulting in the voices of rural Americans being drowned out.

As districts become smaller and the threshold for victory becomes lower, it is possible for more groups to elect their candidates of choice: the smaller the district, the easier it is for a minority group to become a pivotal voting bloc. This is especially significant in the case of lower-income voters. Political scientist Karen Long Jusko has estimated that even if the poorest 33 percent of Americans voted as a unified bloc, they could still only elect their preferred representative in 5 percent of districts. In France, by contrast, one-third of the districts have a low-income majority. “The size of a U.S. congressional district is much larger—by a factor of almost seven—than the average French district,” Jusko notes. “This undoubtedly contributes to the heterogeneity of American congressional districts, and dilutes the electoral power of low-income voters.” Meanwhile, she finds a consistent pattern: the more electoral power poor voters have across countries (and across U.S. states), the higher the level of government social spending.34

Congressional Deliberation

The trade-off in having more representatives, of course, is that it changes how representatives work together. In a small assembly, it is easier for representatives to get to know each other and to have deliberative group discussions. But as assembly size increases, the ability of representatives to deliberate together in a single assembly dissipates. Back in the 1910s and 1920s, advocates for capping the size of the House argued that 435 was big enough. Any bigger and it would be difficult to have meaningful deliberation. As noted above, this was an arbitrary number, yet it captured the idea that the ability of a legislature to function properly can be undermined by the legislature’s size.

Anyone who has sat through any organizational decision-making meeting understands that deliberation in large groups is difficult. Large organizations solve this problem through committees and subgroups. This is also how Congress operates. The House as a whole does not deliberate. Members give speeches, mostly to empty rooms and watchful cameras, with little interest in discussion with each other. Committees and subcommittees hold hearings to debate and develop specific legislative proposals. Party leaders structure voting. The United States passed the point of a single legislative assembly operating as a whole long ago. Whether we like it or not, this is an age of specialization. And in this respect, a larger Congress—possibly paired with changes to deliberative rules and structures—would make deliberations within the committees and subcommittees more robust and representative.

Questions of deliberation are especially important given how much Congress has on its plate. Concerns about congressional efficiency led to the capping of the House at 435, and the issue is only more pressing today. Simply put, Congress has more to do than ever and, as political scientist Kevin Kosar writes, it cannot keep up with its current workload.35 It manages roughly 180 executive agencies. The House hosts hundreds of hearings per year—417 in 2020—and members are so overscheduled that they cannot attend hearings for their own committees.36 Representatives have scarce time even to read all the legislation slated to come up for a vote.37 The 63rd Congress (1913–1915)—the first with 435 seats—managed a budget roughly equivalent to $19.7 billion in 2021 dollars. The 116th Congress (2018–2020), also with 435 seats, managed a national budget of $4 trillion.38 Even before the budgetary and administrative growth that surely lies in the federal government’s future, at its current size, Congress can barely handle all of its duties.39

There is another, related issue that shapes the question of House enlargement: where are all these new congresspeople going to sit? Anyone who has spent time in the Capitol knows how jam-packed it is and how small congressional offices are. Physical space was one reason Congress opted to keep the House at 435 seats a century ago, and the Capitol has certainly not been significantly expanded since then.

Whether or not the House is expanded, Congress should consider changing its strategies for deliberation. The COVID-19 pandemic saw the adoption of a variety of new forms of participation, including virtual hearings as well as proxy voting. These rule changes have their critics, to be sure. But their widespread use signals that there is an appetite and an opportunity for Congress to think creatively about how it functions. In this context, concerns about office space may be less pressing, or even moot. Over the long term, Congress may consider building or renting new space near the Capitol to accommodate new members. In the meantime, new members could use makeshift offices outside of the Capitol complex or employ virtual participation tools. The argument that the House should not expand because it does not have enough room has the formulation exactly backward. The nation should not constrain its political institutions because of office space. Instead, we should forge the political institutions we need, and then figure out the logistical considerations.

As for current members of the House, aside from concerns about losing already-scarce office space, many may fear that with every additional seat, their voting power will diminish. Yet, in the modern Congress, individual members have little power as it is. A larger House could offer members more benefits in exchange for a decline in relative power: a closer connection to constituents and perhaps more opportunities for substantial subcommittee work, since subcommittees could become more significant in a larger chamber. These are the trade-offs. But the current size of the House seems to offer the worst of both worlds. The House is not small enough to function as a reasonably deliberative body. Nor is it big enough to allow for a truly effective division of labor in policy-making, or for districts small enough to facilitate meaningful member-constituent connections.

Parties and Partisanship

The complicator in all of this is nationalized partisanship, and especially hyperpartisan polarization.40 The foundational premise of constituent-member relations in the American tradition is the idea that geographic constituency offers some kind of meaningful unit of representation. However, the nationalization of politics and the metastasizing of the two political parties as distinct “mega-identities” pose a barrier to this vision of representative democracy.41 If Democrats cannot feel represented by Republicans and vice versa, how should one think about the delegate-trustee distinction? And if representatives simply discount the view of constituencies with whom they disagree (largely for partisan reasons), how does that square with our conception of representatives trying to reflect the views of their entire constituency?42

Should representation instead be thought of through the lens of political parties? After all, the single-member district is relatively rare across advanced democracies. It assumes a direct connection between citizens and their representatives. Though this is mediated by party, it is not the same as voting for a party. However, given that so much of voting is now thoroughly nationalized, and given that so many voters are reliably partisan voters, the ideal of dyadic representation—namely, the connection between members of Congress and their constituents—is increasingly difficult to square with reality.43 As a result, it may be time for a broader rethinking of the single-constituency, single-winner district.