2135th Stated Meeting | April 17, 2025 | House of the Academy and Virtual

On April 17, 2025, Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., was honored with the American Academy’s Award for Excellence in Public Policy and Public Affairs. The award recognizes individuals for their distinction, independence, effectiveness, and work on behalf of the common good. The award was presented to Dr. Fauci for his significant contributions to the understanding and treatment of infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and COVID-19. The event included remarks by Dr. Fauci and an interview with Academy President Laurie L. Patton. An edited transcript of the program follows.

Laurie L. Patton

Laurie L. Patton is President of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She was elected to the Academy in 2018.

Good evening. Whether you’re here at the House of the Academy or joining us from around the world, thank you for being with us. Dr. Fauci, we are so happy to be in your presence.

Tonight we are gathered to honor Dr. Anthony S. Fauci with the American Academy’s Award for Excellence in Public Policy and Public Affairs. This evening we celebrate his extraordinary contributions and learn more about his remarkable life.

The Award for Excellence in Public Policy and Public Affairs is presented to individuals for their distinction, independence, effectiveness, and work on behalf of the common good. Tony is the third recipient of this award, following Ernest Moniz and Marian Wright Edelman.

Tony has served this nation for five decades, spanning seven presidential administrations. As Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases from 1984 to 2022, Tony was a tireless and visible advocate for evidence-based policymaking. He helped navigate unprecedented challenges. At the Academy we are proud to claim him as a past author in Dædalus, our quarterly journal. Together with Peggy Hamburg, he wrote “AIDS: The Challenge to Biomedical Research” that appeared in the spring 1989 issue Living with AIDS. He is a clinician, researcher, communicator, and a fierce champion for a healthier, more equitable world.

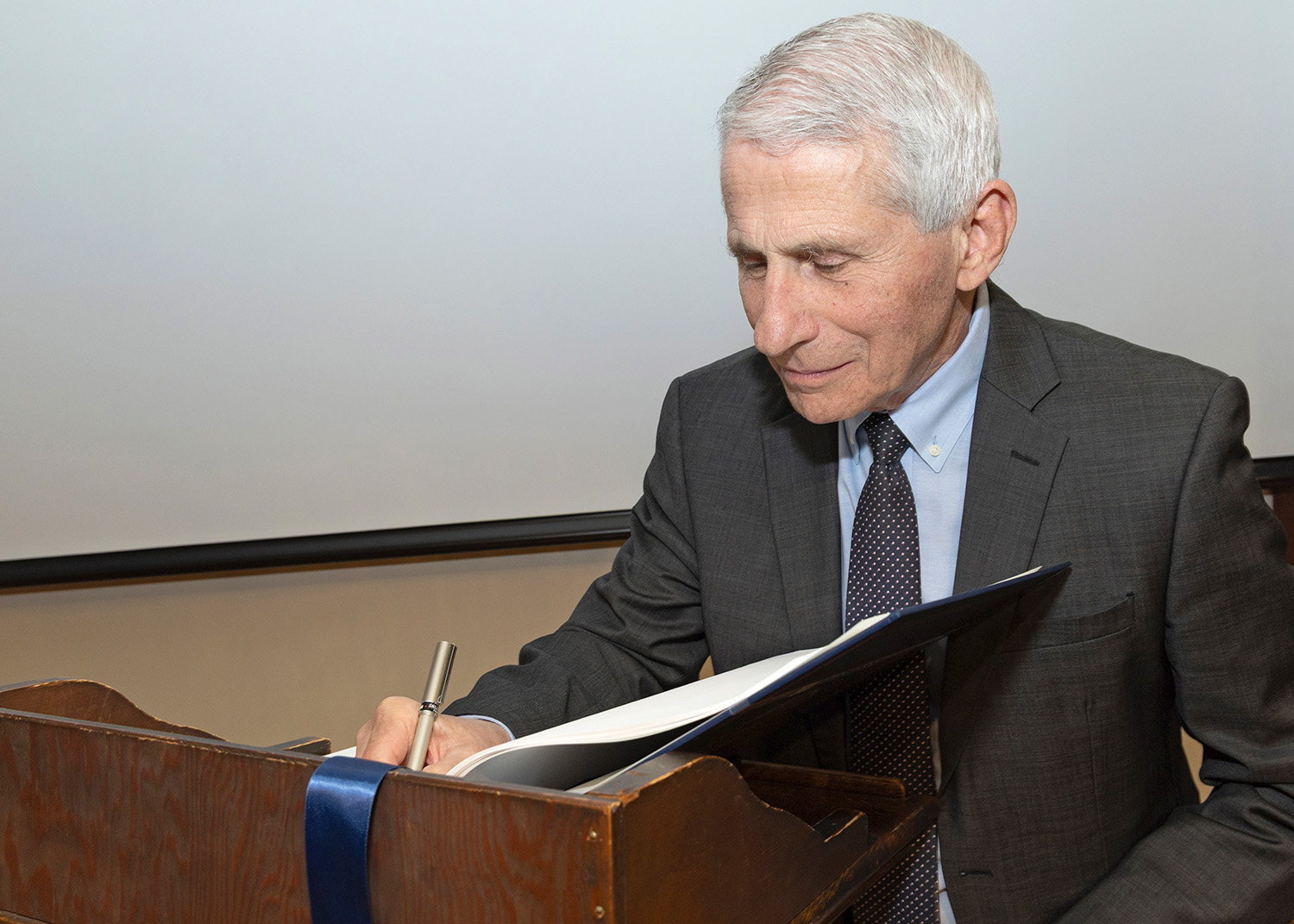

Tonight we honor Tony, but we also have the honor of hearing from him. After I officially confer our award, Tony will join me in conversation about his exemplary life and career as illuminated in his superb memoir, On Call. But first some Academy business. It may not be surprising to know that Tony has been a member of this Academy for over thirty years. But he has been a little busy since his election in 1991, so tonight is a perfect opportunity for Tony to inscribe his name in the Academy’s Book of Members. Each inductee into the Academy signs their name in our Book of Members, thereby joining a living record that includes the signatures of John Adams, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and the generations of Academy members who have followed in their footsteps. Many of you here tonight are part of that legacy.

Nearly 250 years of Academy history have led to the election of health pioneers, including the creator of the smallpox vaccine, Edward Jenner; virologist and the developer of the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk; the surgeon general known for his work on tobacco use and the HIV/AIDS crisis and also a friend of Tony Fauci’s, C. Everett Koop; and infectious disease expert and mentor of Tony’s, Sheldon Wolff. Tony, we invite you to sign your name alongside your fellow members.

It is now my pleasure to confer the Academy’s Award for Excellence in Public Policy and Public Affairs on Anthony S. Fauci, M.D. I will read the official citation.

Citation

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences was founded by a group of patriots who devoted their lives to cultivating every art and science which may tend to advance the interest, honor, dignity, and happiness of a free, independent, and virtuous people.

The Award for Excellence in Public Policy and Public Affairs is presented to individuals for their distinction, independence, effectiveness, and work on behalf of the common good.

For his demonstrated record of serving the public interest over partisanship; championing important ideals, principles, and ethics; and exhibiting courage in the performance of his public service, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences hereby recognizes Anthony S. Fauci, M.D. for his extraordinary leadership, groundbreaking research, and unwavering commitment to public health.

As a young boy, you honed your skills on the basketball courts of Brooklyn, playing point guard with precision, strategy, and unshakable determination. You learned that the role of a point guard is not just to score, but to lead—reading the game, anticipating the challenges, and making the right plays under pressure. Throughout your career, you embodied this same leadership, orchestrating global responses to some of the greatest public health crises of our time.

For over four decades, you have been at the helm of infectious disease research and policy, directing the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. From HIV/AIDS to Ebola, from Zika to COVID-19, you guided the scientific and medical communities with skillful decision-making, ensuring that each move was backed by evidence, teamwork, and a deep commitment to protecting lives. Like an elite point guard, you excelled under pressure, navigating fast-changing circumstances with agility and poise. Even in the face of opposition and uncertainty, you remained steadfast, keeping your eyes on the goal of safeguarding global health.

Leadership is not just about making decisions in the moment; it’s also about guiding the next generation. You have nurtured and inspired countless scientists, physicians, and public health leaders. Through your mentorship, you have not only shaped individual careers but also strengthened the very foundations of infectious disease research and public health, leaving a profound and enduring legacy of excellence.

Physician, researcher, leader in public health, beloved mentor, and recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, you exemplify the Academy’s values of using evidence and knowledge to advance the common good. Your unyielding commitment to science, truth, and human well-being has saved millions of lives, and in doing so, you have inspired future generations to pursue knowledge, serve humanity, and stand resolute in the face of adversity.

Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.

Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., is Distinguished University Professor at the School of Medicine and McCourt School of Public Health at Georgetown University. He served as Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health from 1984 to 2022. Dr. Fauci was elected to the American Academy in 1991.

Thank you very much, Dr. Patton. It is with great pleasure and humility that I accept the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Award for Excellence in Public Policy and Public Affairs. As some of you may know, I have recently stepped down from my fifty-four-year career at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). For thirty-eight years of that time, I was the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

My getting involved in public policy and public affairs for which I am receiving this award was not on my radar screen when I graduated from medical school in 1966 and began my multiple years of residency training in New York City and fellowship in infectious diseases at the NIH. At the time, I had the full intention of expanding my knowledge in the field of infectious diseases, returning to New York City, and practicing medicine in a teaching hospital. But at the NIH, everything changed for me. I became enamored of the concept of clinical research, where what you did benefited not only the individual patient for whom you were caring but also allowed for a multiplier effect, where what you discovered and the clinical protocols that your research led to could be used by physicians and health care providers throughout the country and the world to benefit countless patients that you might not ever see.

I was fortunate that with the help of a generous mentor and with the highly intellectual atmosphere of the NIH, I was able at a relatively young age to develop life-saving therapies for a group of formerly fatal, uncommon (but not rare) inflammatory diseases of blood vessels that led to multiple organ system failure. I became fairly well-known in medical circles and was feeling very good about the fact that most of my patients who might have died were now leading relatively healthy lives.

Then, in the summer of 1981, my world changed, and the era of HIV/AIDS began. I knew this was a brand-new disease and it had to be infectious. I made a career-changing decision at that point, against the advice of my mentors and advisors, to put aside the successful program that I had developed, hand it over to my trainees, and devote myself full time to studying this new and mysterious disease. It was the dark period of my professional career since we had no treatment early on and virtually all of my patients died within months to a year or two from diagnosis.

I felt that I needed to have a greater influence on promoting research and directing more resources to this terrible disease as well as to infectious diseases in general, and so I accepted at a relatively young age the offer to be the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases so that I could have a much greater impact on the area of infectious diseases and immunology. Over the next several years we greatly expanded the resources for research on AIDS, and in collaboration with the pharmaceutical companies we developed highly effective therapies for HIV such that the patients whom years earlier I could only comfort were now put into complete remission, going on to lead normal healthy lives with an anticipated lifespan approaching the general population.

My role as Director of the Institute also gave me the privilege over my almost forty-year tenure of advising seven presidents of the United States on matters of domestic and global public health, from Ronald Reagan to Joe Biden, for whom I served for two years as his chief medical advisor. It was in this context that I became deeply involved in public policy and public affairs in the arena of science, medicine, and public health. Public health challenges emerged with each administration: HIV/AIDS starting with Reagan and sustaining through George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and to a lesser extent with other administrations. Then there were the anthrax attacks following the 9/11 terror attacks, and bird flu during the administration of George W. Bush. There was pandemic flu of 2009, Ebola, and Zika during the Obama administration, and of course COVID during the Trump and Biden administrations. During each of these public health crises, I tried to follow the scientific evidence to guide our public health decisions and communicate these clearly to the American public.

I have summarized the arc of my life and my career from my early childhood until the present day in my recently published memoir—On Call: A Doctor’s Journey in Public Service, which I am looking forward to discussing with Dr. Patton and our audience. Thank you.

PATTON: I want to share a story that’s a little bit of a confession. I’m a former college president who led a college through COVID, and you were omnipresent in our lives at that time. We became de facto health communicators even though we hadn’t been trained in that area. I had a group of about six other leaders, and to get us through COVID we would connect with each other all the time. We had a little mantra. At first, it was “Have you listened to Fauci today? What did he say?” At the end of one particularly difficult moment, when we were opening and other schools weren’t and we were getting a lot of pressure, someone said, “Laurie, did you get your Fauci on today?” And I said, yes! So that was my mantra for two years. I would walk out of the house and say, “I gotta get my Fauci on.” So you are part of my inspirational mantra.

I had the privilege of listening to your book as I commuted back and forth from Cambridge to my home in Vermont, and one of the things that really struck me as I listened to you—you narrated your own book, which is also an incredible feat—was the way you talked in your childhood and particularly in high school about the choice of medicine. You were an athlete and you were also a clearly gifted student who loved the sciences, but something that many people may not know about you is that you also loved the humanities. You were trained in the Jesuit tradition in the classics, and at one point in the early chapters of your book you said that you wanted to bring the classics and the sciences together—similar to what we say at the Academy about the arts and the sciences coming together. And for you, that was medicine. Could you tell us how medicine brings those things together?

FAUCI: It really started earlier when I was a child in Brooklyn, New York. My father had a pharmacy in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn, which was a working-class neighborhood. He had an interesting outlook on the neighborhood. He was a very poor businessman, but he loved the community and felt that the pharmacy should be almost everything to the community. He was a part-time psychiatrist and marriage counselor. He cared about people, especially parents with delinquent children, and there were a lot of delinquent children there. So the idea of service to others was in my DNA, but I wasn’t sure how it was going to play out because I was only eight or nine years old.

I went to a Jesuit high school in Manhattan, Regis High School, and then I went to College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. I liked science and I knew that I was pretty good at science, but I wanted my association with people to go beyond the science that’s related to people. I was more interested in the person who has the disease rather than the disease that afflicts a person. My Jesuit training was very heavily weighted to the humanities. My diploma was a bachelor of arts—Greek classics/philosophy/premed. My courses gave me a feeling of humanity and people, and that’s the thing that essentially drove me. I did my medicine training and was a researcher at the NIH, but my fundamental identity has always been as a physician who cares for people.

PATTON: Are there particular Greek philosophers or thinkers who have stayed with you from your classes?

FAUCI: Well, I translated The Iliad and The Odyssey from Greek to English. It took me three years to do that so that really sticks out in my mind.

PATTON: It’s amazing the way that works. The other thing that I noticed about your high school career is the way you spoke about your basketball playing. You remembered the players, you remembered your rivals, you remembered the people you wanted to beat—what their records were, what their strengths on the court were, and so on. I was particularly struck by that because growing up in a medical family I know that doctors can get super competitive, and it’s clear that you are super competitive in a really wonderful way. But you seem to have channeled it in a different direction throughout your career. Could you say more about that?

FAUCI: I was the captain of my basketball team in a New York City high school, which is really the hub of big-time high school basketball! In my senior year I found out that I was actually quite good. I was the high-scoring point guard. And then we started scrimmaging against college players and I found out very quickly that a five-seven, very fast, good court presence point guard will always get killed by a six-three, very fast, good court presence point guard. So then I decided I was going into science.

PATTON: I also note that throughout your memoir you remember your colleagues almost like they were your teammates. I wonder if you learned the art of friendship in those years of playing basketball.

FAUCI: I did. In the book, I tell the story of one person in particular who I played against in a basketball tournament in high school. He played for St. Agnes of Rockville Center in Long Island and I played for Regis High School, and I met him on the first day when I went to Holy Cross. We became very good friends, and our career paths went through Holy Cross, Cornell Medical School, and fellowship at the NIH. I have a strong feeling about strong friendships and, as I describe in the memoir, I’ve had several of those.

PATTON: The other thing that I’ve noticed throughout, and I think this is connected, is that when you’re talking about managing the AIDS crisis or Ebola or Zika, you refer back to your medical school training and your first few years as a practicing doc with a kind of reverence for the skills that training and experience gave you. I haven’t heard a lot of doctors mention how formative those early years are for the rest of their lives. You didn’t forget that.

FAUCI: I look upon it as a physician’s responsibility to give everything you have to the individual patient. You have to be totally responsible for that patient; you have to focus when you’re in the room taking care of the patient. And even when you leave, you are still responsible for the welfare of that patient. And that became a metaphor when I was in a position of broader influence. I would think of the general public as my patient. During the AIDS crisis, every person who was living with HIV or at risk for HIV became metaphorically my patient. During COVID, I used to feel that the country was my patient and the same attention, commitment, and resolve that I gave to an individual patient in a New York hospital in 1968 is what the country deserved in 2021 and 2022.

PATTON: That’s extraordinary and also a lot to carry. And it is striking in a couple of ways. Your capacity to see the general public as your patient allows you to think about matters of public health. I’m wondering if the transition that you made gradually over several years in leadership from being a physician who treats individual patients to becoming a health communicator was a hard one because the skills of a physician are in many ways different than the skills of a health communicator. Would you describe what it was like to become an effective health communicator?

FAUCI: When I was younger, I observed some colleagues, both scientists and physicians, who made what I consider were some very serious mistakes when trying to communicate with the general public. Their mistakes helped me to develop some fundamental principles of communication. It didn’t happen overnight. It was a gradual process.

The first thing is, know your audience. The second thing is, be very precise and stick with one message. It’s sometimes a failing of people in medicine and science to convey every detail in a single speech or presentation. I learned, and I’m very fierce about this, that the purpose of communication is not to show the audience how smart you are. It is to get them to understand what you’re talking about. Many people give a presentation as if they’re explaining the supplemental figures to a Nature paper!

PATTON: Earlier you mentioned metaphors. One of the things that you’ve given the world is the idea of the AIDS cocktail. And it’s a metaphor that I use in my administrative work. In your book, you explain what it meant to add drug to drug to drug to make something effective in the end, even though it wasn’t the final cure. Whenever I try to explain what goes into solving a complex problem, I’ll say, “It’s like the AIDS cocktail.” I owe that to you. It’s an effective use of a metaphor that is powerful.

FAUCI: In 1981, as I describe in the memoir, I turned the trajectory of my career around overnight and decided I was going to start seeing exclusively these young, previously healthy, almost all gay men who had a disease that would kill them in twelve to fifteen months. The years from 1981 to 1986 were really the dark years of my medical career because everybody that I was taking care of was dying. And that was tough to take. But it was an incentive to do something about it, which was one of the reasons why I took the job as the Director of NIAID because I needed to do more than just take care of patients.

The first drug was introduced in 1987 and it diminished the level of virus not below detectable level but just enough to have a person go into a temporary remission. But inevitably the virus bounced back. It’s an RNA virus, and there are going to be mutations. Two or three years later we had two drugs and the virus went down even further, but never below detectable level, and it always seemed to bounce back in most people. Then the incredible transforming year of 1996, when the protease inhibitor was introduced for a triple combination that for the first time ever did something that I quite frankly would never have imagined we would be able to do: it brought the level of virus to below detectable level and kept it there indefinitely. People who previously would be going into hospice were looking to get their old jobs back. It was a miraculous advance.

It was a long arc—from 1981 to 1996—and then the drugs got better and better so that by the time we got into 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005, you could have one pill with three drugs in it that would put somebody into remission. To me that is one of the most dramatic examples of the power of basic and clinical biomedical research, where you could go from taking care of one person to helping groups of patients. I’ve taken care of hundreds, if not thousands, of people with this disease who suffered and died, and then we turned that trajectory around completely so that people were walking out of the hospital and getting on with their lives. Biomedical research at the NIH is being threatened right now, and there are going to be a lot of lives lost if we pull back on our efforts because we are leading the world in basic and clinical biomedical research and it would be a terrible thing if we lost that.

PATTON: In your book, you describe a conference in Canada where the data were presented and everyone spontaneously applauded. But you yourself are not a high drama person.

FAUCI: No.

PATTON: Everyone loves that about you. I want to ask about this incredible capacity that you have to remain calm. In your book, you talk about how you engaged with activists like Larry Kramer. I know as a college president that sometimes you need to be super wonderful on the outside, but at the end of that I’m saying to myself, “oof, that was really hard.” The way you described your relationship with Larry Kramer, who accused you of murder and a few other things while you were working your butt off to do the opposite, that’s tough and to have that be on a national stage is even tougher. The fact that you kept that relationship and became a deep friend of that person is such an extraordinary story. I’d love to hear you say a little more of how you think about that now.

FAUCI: Larry Kramer was one of many activists, and it was a situation where the driving principles of their activism were correct. At the time, the biomedical research community and the regulatory community had an approach that worked very well for other diseases, like hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers. Protocols had strict entry and exclusion criteria with no room for anything outside of the clinical trial because you didn’t want to interfere with the pristine nature of the clinical trial so you can get a definitive answer. The FDA had a strong track record of ensuring the safety of the American public by approving drugs that worked and were safe. It took an average of seven to ten years to get a drug or vaccine approved.

These groups of young men were terrified. They were ill and knew that from the moment they developed clinical disease they would likely be dead in ten to fifteen months. And they were saying, “You know, your paradigm doesn’t work for us. We want to be able to sit down with you and have some input into the design of the clinical trial and to get the FDA to be a bit more flexible. We need to have a seat at the table.” And, interestingly, it’s true. The scientific community—it sounds horrible in hindsight—was saying, “We know what’s best for you because our process has been successful for so many years.” To get our attention, the activists adopted provocative, iconoclastic, disruptive, and theatrical tactics.

When Larry Kramer wrote an article for the San Francisco Examiner in 1988 entitled “An Open Letter to Dr. Anthony Fauci,” he referred to me as an incompetent idiot and a murderer. He got my attention for sure. What I did then was one of the best things that I’ve ever done in my career. Instead of running away from them the way almost everybody in the scientific community did, I said, “Let me listen to what they’re saying.” And what they were saying was making absolutely perfect sense. If I were in their shoes, I would be doing exactly what they were doing. After that, I embraced them and listened to them.

PATTON: Against the advice of your staff.

FAUCI: I had to get rid of some of my staff who refused to interact with the activists. I wanted them to come to our meetings and to have input into how we could do better, and there were several members of my staff who didn’t want them anywhere near us. So it was a bit of a clash, but it was absolutely the right thing to do. So that’s how the relationship with Larry went from being antagonistic to having him become a collaborator, a contributor, and one of my close friends.

PATTON: It’s an extraordinary story. And your narrative of being with him near his time of death is also so moving to read.

FAUCI: Yes.

PATTON: I want to move to other diseases and other health threats. Right after 9/11, you had to drop your work on AIDS and manage the bioterror scare. I imagine that shift was a loss and not an easy one. The public was scared and you had to reassure them in a different way than what you had to do with AIDS. Could you talk a little bit about the specific communication challenges of the different diseases that you oversaw?

FAUCI: It gets back to what I said previously about knowing your audience. When I was talking to the community of persons at risk for HIV, it was one audience. I’m sure you all recall that right after 9/11 when we had anthrax attacks through the mail, everybody thought Al Qaeda was responsible. People were worried about more anthrax in the mail, but they were also worried about anthrax spores in the subway in New York City or on the Metro in Washington, D.C. I realized that I was addressing the American public. I needed to tell them what we knew without scaring them. It’s a delicate balancing act. Right from the beginning I was very skeptical that Al Qaeda was responsible because Al Qaeda had already shown that they were pretty competent in killing people, so to send a couple of spores in the mail wasn’t Al Qaeda’s style.

I had to tone down the fear that everybody had about even opening their mail. Remember that the post office was irradiating the mail. I geared my message to the audience and to the reality of what the problem was. There’s another aspect about the anthrax attack that I explain in the book. George W. Bush, right after the anthrax attack, designated $1.5 billion to develop countermeasures against bioterror. The funds would be going to either the Department of Defense or to the NIH. I convinced President Bush to give the funds to the NIH since the worst terrorist is nature itself. I was more worried about naturally occurring infections like a pandemic flu. I didn’t know about COVID at the time. I said that we should take that $1.5 billion and use it to develop countermeasures against the obvious bioterror of pathogens, which would be smallpox, tularemia, botulism, and the like. We did spend some money on that, but the bulk of it we invested in trying to develop better drugs and vaccines against naturally emerging infectious diseases.

PATTON: I want to come back to your relationships with leaders as you led the nation on public health. Tiny footnote to the anthrax scare: There were a couple of cases in which there was no known exposure and the press was all over that. You had to manage that kind of fear as well.

FAUCI: Aerosolized spores can lead to secondary and tertiary transmission. A letter that went from New York to Connecticut still had some spores on it, and when the recipient opened the mail in Connecticut, we couldn’t trace it to any specific post office because the letter went through more than one post office.

PATTON: During the COVID pandemic, one leader said, “We need to get this all wrapped up by Easter,” and you replied, “Sir, the virus doesn’t understand Easter.” You had an incredible friendship with both Bushes, you were close to Obama, and you worked with the Clintons. You have said no to several presidents, which is admirable. How do you convince leaders to accept or act on scientific information?

FAUCI: The first time that I went into the White House to brief Ronald Reagan on HIV/AIDS a friend of mine, who had spent six years in the Nixon White House and then was in the Department of Health and Human Services, a guy from Boston who went to Boston Latin High School, gave me some advice. He said, “You’re going into the White House to advise a president for the first time. Do yourself a favor. When you go under the awning of the West Wing and go down to the lower level, before you go to the Oval Office whisper into your own ear that this might be the last time I’m going into this building. Because you might have to tell the president or the vice president or his advisors an inconvenient truth that they might not want to hear. And they might not ask you back.” But then he said, “But if in fact that happens you’ve got to understand that the White House is a very heady place.” I’ve been in the White House hundreds of times, but when you go in the White House you instinctively get a feeling that isn’t this great. I would love to get asked back. People make a mistake, maybe subconsciously, of telling an authority something that is not necessarily true, but something they’d like to hear because you don’t want to be the messenger that gets shot and not asked back.

So my friend told me, “Just go in there and always tell the truth even if it’s something that might get that person unnerved.” And I did that with every single president and it worked very well except for one occasion. I had to tell President George H. W. Bush that he was not giving us enough resources. He respected my position, though he didn’t necessarily do everything I said. And the same thing with Obama. He would listen very carefully. He might not agree with you, but he always respected what you said. And that worked well for thirty-eight years until the end when I was put in the position of having to directly contradict the president, which was very difficult.

PATTON: For much of your career, you were heard, but then there have been these spectacular moments when what you said was simply not heard or was disagreed with in a way that made your job hard. And those are different kinds of things. You had scientific experts disagreeing with you about AIDS, and then you have other folks who deny the power of science altogether and that’s a different kind of not being heard.

How do you manage not being heard when you’re dealing with such a massive question of health?

FAUCI: You keep talking.

PATTON: And keep saying the same thing?

FAUCI: Well, no. One thing that I’ve learned is that when people disagree, particularly the antivax people or people who don’t believe that HIV causes AIDS—they thought it was a behavioral thing—you can’t be confrontational. You have to try to understand where they’re coming from and convey your position, and hopefully they will be open enough to accept the data. But there’s always going to be a core group of people that no matter what you tell them, they are not going to believe it, and they’re going to have their own ideas. For example, there are people today, and not a small number, who believe complete fabrications because it’s spread by what I call the cesspool of social media, like COVID vaccines have killed more people than COVID itself, which is completely crazy. The data are so crystal clear if you compare deaths of unvaccinated people and their hospitalizations with deaths and hospitalizations for vaccinated people. The curve of hospitalization and death hits you like a Mack truck.

PATTON: This is what I mean by “getting my Fauci on” because though we say, “The science is clear and that’s what it is,” we can’t cite the data like you just did, and that’s the skill that I think is so necessary. Staying with COVID for a second, was it a different kind of challenge for you?

FAUCI: It was. There’s always some politics involved in whatever you do in Washington, and not necessarily politics in a negative sense because sometimes the politics can lead to positive things. But the issue with COVID was so politicized during those early years that that’s when I had to speak up. In the beginning we were saying what we had to do: people needed to wear a mask, people needed to physically distance. And the Trump administration and the president went along with that, but he was hoping, because the election was coming up, that the virus would disappear like magic as we got into the warmer weather toward the end of March and the beginning of April. And that’s when I told him the virus doesn’t respect Easter. He wanted everybody back in church on Easter and I said, “I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

He would get up in front of the audience in the press room at the White House and say, “Oh, it’s going to disappear like magic” and then the press would ask me, “What do you think?” And I’d have to get up and say, “No, I don’t think that’s going to happen.” And when it became clear as we got into April that it wasn’t going to disappear like magic, he started to evoke magic elixirs and say, “Ah, I heard from someone that hydroxychloroquine works.” Or “I heard that Ivermectin works.” And he would get up and say, “Well, you know, I heard from good people that it works so I think it works,” knowing that I’d have to then stand in front of the microphone because the press would ask me and I’d say, “No, I’m really very sorry, but the data show that not only does it not work, it can actually harm you.” And the people in the White House were infuriated with that, less so than the president. The president wasn’t that upset about it. The people around him were really furious because they thought I was deliberately doing it to undermine him. What they didn’t understand is that regardless of who is president, I had to tell the truth. I have a great deal of respect for the office of the presidency, and it was very painful for me to publicly disagree with the president of the United States. Getting back to the metaphor of my patient, the public was my patient and it was like going into a room with a patient and telling them something that’s not true. I just couldn’t do that. And that created a real firestorm against me.

PATTON: To disagree with the president in your calm manner was so impressive to those of us who were witness to it. I’m going to end this part of our conversation with something a little more personal. One of the things that really moved me about your book was the way that you carried certain moments in your career with you. The patient who became blind one afternoon due to secondary comorbidities in the early AIDS years. You saw him in the morning and then he was blind in the afternoon. The Ebola patient in Uganda, when you knew you could have done something, but at that moment in that situation you couldn’t help that young man. That was very powerful because you revisited those images and they almost seemed to me like ancestors or people that you carry with you no matter where you go. Who are you carrying with you today?

FAUCI: What bothers me most right now is what I think bothers most people in the audience, and that is the direct attempt to destroy the scientific enterprise in this country. It’s painful because it’s very dangerous. Things are happening haphazardly; for example, the cuts to USAID without realizing that the PEPFAR program that I had the privilege of putting together for President George W. Bush has saved 25 million lives over the last twenty years, but 60 percent of the drugs that get distributed in southern Africa are through USAID. So when you pull the rug out from USAID there’s going to be a substantial number of people who are waiting for their next dose of medicine who are not going to get it. If you look at a corporation and say, “We’re going to slim it down to make it more efficient by cutting x%.” If it doesn’t work and the corporation doesn’t do so great, well, the most you’re going to lose is money. When you do this to the biomedical research and public health enterprise what you lose is lives. So that’s the thing that’s weighing very heavily on me right now.

PATTON: In ending this part of the conversation, Dr. Anthony Fauci, I want to thank you so much for thinking of the nation and the world as your patient.

FAUCI: Thank you.

PATTON: We have time for a few questions from our distinguished audience.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Could you comment on the challenges that we face because of the reduced development of new antibiotics? The core issue seems to be the lack of financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies. Highly effective antibiotics, such as cephalosporins or macrolides, are typically taken for a week or two. In contrast, drugs for chronic conditions like high blood pressure or high cholesterol are taken daily, providing a steady, long-term revenue stream to these pharmaceutical companies. This makes investment in antibiotics far less attractive to drug companies. Where will the funding for new antibiotic research come from if the pharmaceutical industry has little motivation to invest in it?

FAUCI: In the last year of my directorship of NIAID I tried to develop a drug development program in collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry to de-risk the amount of investment that they need to make because for certain antibiotics or antifungals there’s not going to be a large need for them throughout the country and so there’s no real financial incentive for the pharmaceutical companies. NIAID put in a fair amount of money. That money has now been taken away with the cuts to the NIH, but your point is very well taken. If there is a needed intervention that is critical for public health but it’s not a profit maker for the pharmaceutical company, then some entity, in this case the federal government, has to make an investment to de-risk it for the pharmaceutical companies. Unfortunately, they are cutting $20 million out of a $47 million budget for the NIH, and if that stands, which I hope it won’t, it’s going to be a disaster.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: First, thank you for your service. I have a two-part question. Can you estimate when the next highly infectious and lethal pathogen will emerge? And looking back, what would you have done differently and what lessons can we use for the next pandemic?

FAUCI: Thank you for these two very important questions. To answer the first question, I can say with a great deal of certainty that we will have another pandemic, but I can also say with a great deal of certainty that I have no idea when that will occur. If you look at the history of pandemics, from the plague of Athens in the fourth century BC all the way to the bubonic plague in the fourteenth century and smallpox and measles in the Western Hemisphere in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries and then pandemic flu in 1918 and then some minor outbreaks of flu and then the big one with COVID, it’s clear it is going to happen again. We know that there will be another pandemic, but we don’t know exactly when. That’s the reason why pandemic preparedness, which we put together before I left NIAID, has to be a perpetual effort, which unfortunately and seemingly paradoxically has now been discontinued.

What would we have done differently? No one is perfect, especially when facing a horrendous outbreak. One thing that I believe was not fully understood by the public is how the scientific process works in such situations. Science is not static—it’s a process that evolves as new data and evidence become available. That means recommendations and guidelines may change as we learn more. And that’s not inconsistency; it’s the self-correcting nature of science. When the facts change, it’s our responsibility to adjust our approach accordingly.

There are a lot of things that we would have done differently if I knew in January 2020 what we knew in June 2021. For example, the original understanding was that COVID was very similar to SARS from 2002 and 2003, which was very poorly transmitted from person to person and could easily be contained by public health measures of identification, isolation, and contact tracing. In contrast, SARS-CoV-2 was highly transmissible. The next thing we didn’t know is that, unlike other respiratory diseases, 50 to 60 percent of the transmissions were from someone who had no symptoms. The whole idea of covering your cough didn’t really help, because 60 percent of people spreading the virus had no symptoms at all. That has a big impact on physical separation, ventilation, and whether you wear a mask or not. If we were doing January 2020 over again and seeing what was going on in China, we would have said, “Everybody, start wearing a mask now.”

Think back to January 2020—there were three people known to be infected in Washington state who had come back from Wuhan. If the health officials told you that everybody should be wearing a mask and do physical distancing, nobody would have listened because we had no idea what was going to happen. The bottom line is this: we have to be humble enough to admit that while we weren’t perfect even with what we knew, there were also things we didn’t know—and as new evidence emerged, we had to update our recommendations based on the scientific process of gathering the information. Some people see that as scientists flip-flopping and say we shouldn’t trust science. The anti-science crowd jumps on TikTok and other social media, and suddenly their message reaches millions.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: How readily do you think the NIH is going to be able to return to normalcy after what’s being done to it?

FAUCI: I’m very concerned about that. I was going to use the word pessimistic, but I don’t want to say that because fundamentally I’m not a pessimistic person. But when you take money away from scientific and medical projects, people are going to suffer. People who need the intervention now, who are living with HIV and need their next dose. And then there’s also the delay in progress and advances against diseases for which effective treatments might be available in the next year or two. The other effect is the disincentive for people to go into science and medicine when they see what’s happening to highly qualified scientists who are getting indiscriminately fired. I think it’s going to take years to recover. The United States is a leader in so many different things, and two that stand out the most are the biomedical research enterprise and our universities. And look what’s getting attacked.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What should we do as a public to try to combat the attack on science?

FAUCI: Speaking out about what’s happening is important. But voices from places like Boston or Harvard may not carry much weight with those who need to hear them most. Things will change when the people who expected something different recognize the reality they now face. That said, staying silent isn’t an option. We must speak up. Being passive is not acceptable.

PATTON: I would like to remind everyone that the Academy will continue to convene its pop-up conversations on the issues that emerge as a result of all of the things that we’re experiencing in our world. Our next conversation will be on tariffs. We are also planning a conversation on the limits of executive power as well as one on the relationship between democracy and autocracy. Stay tuned for these upcoming events as we continue to speak up and engage with these really tough issues of our time.

The Academy is deeply invested in long-term solutions in all the areas pressing on us today. We need people to reimagine and rebuild, and we invite all of you as Academy members to do that with us.

I want to thank you, Tony, for your candor and for your remarkable example. The Academy is so proud to honor you tonight.

© 2025 by Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.

To view or listen to the presentation, visit the Academy’s website.