2139th Stated Meeting | October 12, 2025 | House of the Academy

The closing program of the Academy’s 2025 Induction weekend featured a presentation by new member David Dunning on the psychology of overconfidence and its influence on decision-making, followed by a conversation with Academy President Laurie L. Patton. An edited transcript of the presentation and conversation follows.

Laurie L. Patton

Laurie L. Patton is President of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a position she started in January 2025. Prior to the Academy, she served as the 17th President of Middlebury College. President Patton was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2018.

It’s my pleasure to welcome you to the final program of our Induction weekend. It is wonderful to have one more opportunity to spend time with friends, new and old, and to learn about the work of a new member.

Our presenter today is David Dunning, the Mary Ann and Charles R. Walgreen Jr., Professor of the Study of Human Understanding and Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan. I asked him what it was like to be a Walgreen Professor, and he admitted that his prescriptions were at CVS, so that’s the kind of humor we can expect this morning!

David’s research focuses on the psychology underlying human misbelief and social misunderstandings. In his most widely cited work, he showed that people commonly hold flattering opinions of their competence, character, and prospects that cannot be justified from objective evidence—a phenomenon that carries implications for health, education, the workplace, and economic exchange. David’s other research examines decision-making more directly. He explores how people actively distort their reasoning to favor preferred conclusions and avoid threatening ones, even down to the level of what they literally see. Please join me in welcoming David Dunning.

David Dunning

David Dunning is the Mary Ann and Charles R. Walgreen Jr., Professor of the Study of Human Understanding, Professor of Psychology, and Associate Chair for Faculty Development at the University of Michigan. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2025.

Good morning. I want to thank President Laurie Patton and Chair of the Board Goodwin Liu for inviting me to provide some remarks this morning.

I’ll begin with a celebration of the human brain and the genius of its neural structure. A Salk Institute study claimed that the average human brain can store 1 petabyte of information, which is roughly the amount of information found in four Libraries of Congress. That amount of information allows us to approach novel situations and to be able to problem-solve. We are an adaptable species. There’s only one other species that is as resilient as we are, and it’s the tartigrades.

Let’s start with a quiz. I’m going to show you some instances of daily experiences, and I want you to surmise the theme that unites them. Here are the instances:

Struggling with a can opener

Bumping elbows at the dinner table

Hard to find a friendly school desk

Using ill-fitting scissors

Uncomfortable using a spiral notebook

Ink-smudged hand while writing

What theme unites all these instances?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Left-handedness.

DAVID DUNNING: Correct. These are some daily occurrences for a left-handed person in a right-handed world. Roughly 11 percent of you have an advantage in knowing what this theme is because you live it. Many of you may have come to some other reasonable theme, but not the one we inserted. It’s not a theme you experience. What’s interesting is that we have valid lived experiences, but we don’t necessarily know the lived experiences of others.

We’ve done a study of left-handedness versus right-handedness. Almost two-thirds of left-handers know what we’re talking about after seeing this list. Only one-third of right-handers do. We’ve also done a study with Black respondents versus white respondents, in which we presented instances of daily discrimination that Black respondents are more prone to experience. We found that 50 percent of Black respondents recognized the theme within two instances. For white respondents, it took five instances before 50 percent of them recognized it. If we describe things that women do on a daily basis to protect themselves physically, women recognize the theme far more successfully and far earlier than men. I assume the rich don’t know the lives of the poor. The poor don’t know the stresses of being rich.

We all live with tremendous amounts of knowledge, given the 1 petabyte of information that we store in our brain. By the time we are sixty years old, if we’re an English speaker, we will know 48,000 words and their meanings. That’s astonishing, but there are over 600,000 entries in the Oxford English Dictionary, and that’s before you get to words that are not in English and don’t have an English translation, like the Japanese concept of amae, which is to depend and presume upon another’s love or bask in another’s indulgence. Or the French word ilinx, which is the sudden urge to perform minor and unnecessary acts of destruction. Or the Germanesque neologism sonder, which is the realization that each passerby in the street has an inner life that’s as vivid and complex as your own.

It was Karl Popper who said that the main principle about our ignorance is the fact that our knowledge is finite, while our ignorance must necessarily be infinite.

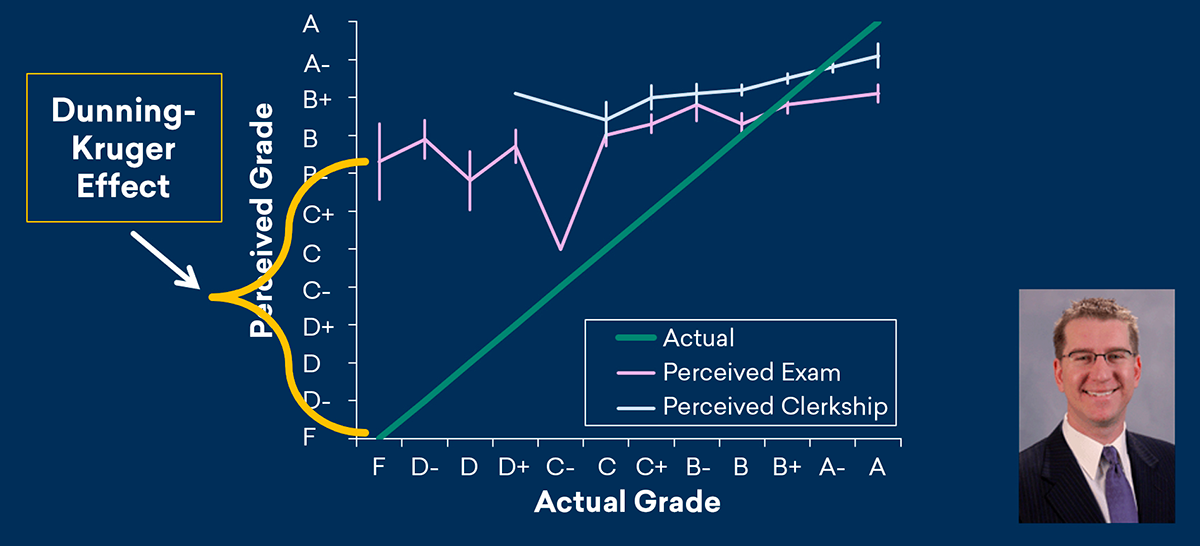

In our research, we’ve looked at particular areas of skill in which you can have expertise, illustrated, for example, by medical students in an OB/GYN rotation or clerkship. At the University of Florida in Jacksonville and at Shands Hospital in Gainesville, 1,100 third-year residents were asked after they finished their final exam, “How well did you do on the exam? And how well did you do on the clerkship?” Figure 1 shows their actual grade on the exam and on the clerkship compared to their perceived grade.

Figure 1: Medical Residents in Obstetrics/Gynecology Clerkship

R. K. Edwards, et al., “Medical Student Self-Assessment of Performance on an Obstetrics and Gynecology Clerkship,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 188 (4) (2003): 1078–1082.

What we see is that the top people underestimate themselves a little bit, while the people at the bottom are getting F’s and D’s on the exam, but they think they’re getting a B or a B minus. On the clerkship itself, they think they’re getting a B plus when they’re actually at the bottom of their class. Those who don’t know don’t seem to know that they don’t know, and they don’t have the expertise that they thought they had. There’s a gap at the bottom.

That gap has come to be known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. By the way, the photo in the figure is of Justin Kruger, a professor at New York University. The problem that we described is that ignorance is not only infinite; it is often invisible. You just don’t know that you don’t know. The way I would describe it is that those who lack expertise lack the expertise that is necessary to realize just how much expertise they lack. This has been demonstrated in a number of areas and with different groups of people, such as with poker and bridge players, debate teams, computer programmers, surgical trainees, public health emergency responders, the general public’s ability to tell fake news from real news, health literacy, financial literacy, aviation students, gun owners, and even wine tasters. Those who don’t know don’t know that they don’t know. And we can actually go further than that. We should not expect them to know, and if they knew, they would work harder to correct their lack of knowledge.

A couple of weeks ago, this was demonstrated in chess. The study just went online, and it is a comparison between an actual chess ELO rating and a perceived ELO rating. What the study found is that people tend to believe that their rating underestimates their true ability by up to 180 points on average.

What does that mean? ELO ratings allow you to forecast the likelihood that the player with a higher number will beat the player with a lower number based on the degree of separation.

One quick side note. For those of you who know about the Dunning-Kruger effect, there are some people who say it’s just statistical noise that is producing it; that it is simply an artifact. What the critics tend not to realize is that there is an established literature on how you correct for that problem, and others have examined the effect referring to that literature.

Back to the chess study. What we get is a hefty overestimation of self. Those who lack expertise don’t necessarily know they lack expertise. They simply don’t have the expertise to recognize it.

Now let’s go back to the genius aspect of being a human being. As a human being you can approach a novel situation and not know the answer, but you can arrive at an answer quickly. We did a study in which we asked two questions about geography: 1) In which season (in the United States) is the earth closest to the sun: spring, summer, fall, or winter? and 2) Which of the following best describes Africa’s location: entirely in the Southern Hemisphere; mostly in the Southern Hemisphere; mostly in the Northern Hemisphere; or entirely in the Northern Hemisphere? In samples we collected and in American samples in general, respondents are about 80 percent sure that they’ve answered correctly the question about the season in which the earth is closest to the sun, but only 15 percent of them gave the correct answer. The earth is closest to the sun in winter. Most people think it’s summer. On the question about Africa’s location, they are about 65 percent sure they’ve answered the question correctly, but only 24 percent gave the correct answer. Though Africa is in the Global South, it’s actually mostly in the Northern Hemisphere.

Part of the problem of not knowing that you don’t know is our genius. We have enough in our brains to conjure up a reasonable answer—the psychological term is to confabulate—and it may be the correct answer. Our genius allows us to approach new situations correctly, but sometimes it creates an answer that is a fiction. And that’s a tremendously fraught thing because it can lead us into a cul-de-sac and make us think we understand that we don’t understand.

But that is how our brains operate. That is part of our cognition. In preparing for this talk, I went to the University of Michigan’s version of ChatGPT and asked it, “What do people mean when they use the phrase, ‘You should try to eat the taco upside down?’” U-M GPT answered, “It’s a humorous or playful suggestion. It can sometimes pop up in social media memes, online discussions, or as part of friendly banter.” I was impressed with the answer because I had just made the phrase up. Then U-M GPT continued: “The phrase can be a metaphor for looking at familiar things in a new and unconventional way, encouraging creativity or the willingness to break from tradition.” Hmm, okay, that’s what I must have meant. U-M GPT continued: “The phrase can also be used as a parody of overly life-hacky or silly food advice, poking fun at the flood of strange suggestions found on the internet.” Yes, there are indeed strange suggestions found on the internet!

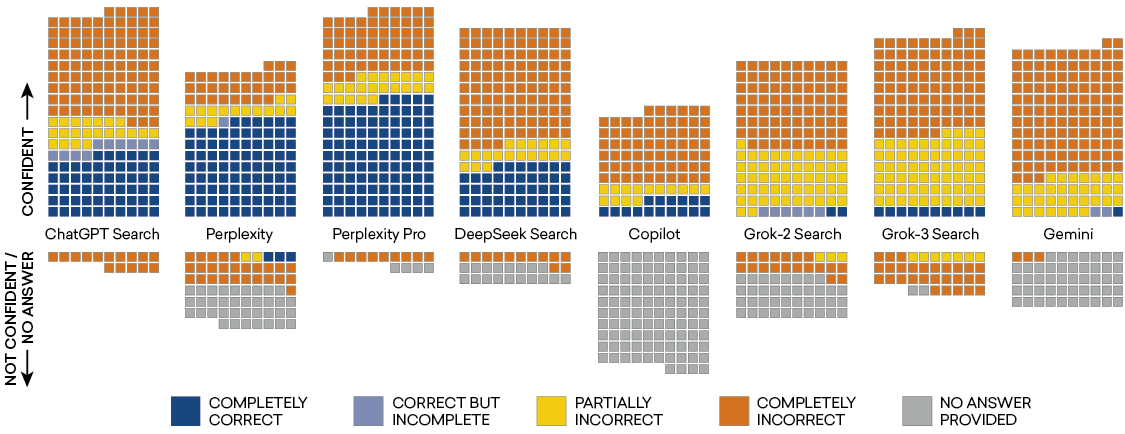

We all know about AI hallucinations. The psychological term is confabulation. Earlier this year, there was a study from the Columbia School of Journalism in which chatbots were given excerpts of news articles and asked to come back with the article’s headline, publisher, and the URL where the quote came from. If we look at the results in Figure 2, the dark blue means completely accurate; light blue is mostly accurate; yellow is mostly wrong; orange is completely wrong; and gray is no answer provided. We know that AI will return an answer. That’s what it’s meant to do, but it doesn’t necessarily come up with the right answer. Above the bar are the returns in which the chatbots don’t hedge at all about the information they are giving. They are perfectly confident. All of us should be concerned about that.

Figure 2: Generative search tools were often confidently wrong in our study

The Tow Center asked eight generative search tools to identify the source article, the publication, and URL for 200 excerpts extracted from news articles by 20 publishers. Each square represents the citation behavior of a response.

K. Jaźwińska and A. Chandrasekar, “AI Search Has a Citation Problem,” Columbia Journalism Review (March 6, 2025).

My other favorite example is Humanity’s Last Exam, which has 2,500 questions that are esoteric, technical, and specialized. As of April 2025, the best chatbots get 25 percent of the questions correct. The worst get only 3 percent correct, but they’ll report that they’re getting over 80 percent correct. And like these AI agents, that’s what our brain does as well. It gives answers, even when it shouldn’t, with confidence. And, importantly, it’s the cognitive and informational part of our brain, not the emotional part, that supplies the confidence. It’s not self-deception, rationalization, or ego. It’s just the way that we think.

Now, ego does matter eventually. We did a study about ten years ago in which we tested business students on their emotional intelligence. After we gave them feedback, we offered to sell them a self-improvement book, The Emotionally Intelligent Manager, for half price. What we found is that 64 percent of the students at the top quartile of performance wanted the book. For the students in the bottom quartile, only 20 percent wanted the book. We attribute those results to ego.

In terms of dealing with information in the world, more responsibility is being put on each of us. We have to figure out our retirement funds. We’re responsible for our own health care. We’re told to do our own research. But how do you do that when you aren’t an expert yourself?

These data may not be exact, but about 80 percent of people say they consult Dr. Google for medical information, diagnosis, and treatment. For those who go to a doctor, they are told that the diagnosis from the internet is wrong about 30 percent of the time. We don’t have data for those who don’t go to the doctor. This leads me to my next point about expertise and the lack of it.

We’re currently doing research in which we present some scientific headlines and ask if the statements are true. In Figure 3, we have some scientific headlines under Set A and then the reverse of those statements is under Set B. For example, one statement in Set A says, “Pure alcohol contains more calories than fat.” Under Set B, the statement is, “Fat contains more calories than pure alcohol.” One group gets Set A, the other group gets Set B, and we ask each group if the statement is true or false. We then take the percentage who said Set A was true and the percentage that said Set B was true and use the average.

Figure 3 | |

|---|---|

Set A

| Set B

|

Now, the average should be 50 percent because if 70 percent think Set A is true, then 30 percent should think Set B is true. For each item, when we take the average and compare it to 50 percent, what we tend to see is that most people see the statements as true well over half the time. People have a bias toward seeing things as true.

In another experiment, we had people answer a science quiz so we could determine how knowledgeable they are about science and how good they are at spotting the true statements. They do somewhat better at it the more knowledgeable they are about science in general, but the real superpower associated with science knowledge is being able to deny false facts. That’s what you get with expertise: the ability to spot falsity.

Let’s talk for a moment about education. What does it do? Well, first, it makes you more knowledgeable. But philosopher and writer Anatole France said that an education isn’t how much you have committed to memory, or even how much you know. It’s being able to differentiate between what you do know and what you don’t. To study that, we went to two college classes. One class is the comparison group and the other class is the treatment group. At the beginning of the semester in both classes, the students are asked, “Are you familiar with these psycho-legal concepts?” Now the treatment group was a psychology and law class. At the end of the semester, the students in that class were asked, “Do you know these particular psycho-legal concepts?” What’s special about these psycho-legal concepts is that they don’t exist. They were never presented in class, and we know this because we made them up in our office.

What we found was that 83 percent of the students expressed some knowledge of these nonexistent concepts, much more than in the comparison class. And some of that residue remained two years later, when we contacted as many people as we could from both classes. It seems education can make it harder to understand where your circle of competence ends.

But the question on tap for this morning is why do fools think they are wise? I hope I’ve given some answers for that, but it’s important to note that the fool is each and every one of us. A person is wise when they realize they will have their moments when they are the fool. It will happen at unexpected times. And the key is to be prepared to know how to recover from that.

That’s the concept of resilience, which a good business management school will teach you. Be resilient against unexpected error and be resilient against overconfidence. A wise person will realize that they need to surround themselves with other people who will make them smarter, and they recognize that they should return the favor because it is in working with other people that we avoid everything that I’ve been talking about today.

People often ask me two questions about this work. The first question is, what are your Dunning-Kruger spots? Where do you experience Dunning-Kruger? I tell them that if Justin and I are correct in our theory, then I am the last person you should ask about where I experience Dunning-Kruger. Ask my friends, who will be very willing to tell you but they kindly won’t tell me.

The second question that I’m asked is, how does this influence how I approach life? I have several answers, but the key answer is this. Philosopher Robin Collingwood said that a person ceases to be a beginner in any given science and becomes a master in that science when they have learned that they are going to be a beginner all their life. Now, I am old and tired, but I realize I can never be at rest. The world is changing, and there are going to be new challenges. I embrace that because it means there are going to be new inspirations and fascinating things to do. And I can’t wait to get started.

What we know is that what is true for the individual is also true for the community, the group, and the nation. If I find that I’m always closer to the starting gate than I am to the finish line, then that has to be true of any group and of the nation as well.

In 1780, a group of sixty-two men, mostly in or near Boston, chartered an institution to cultivate every art and science which may tend to advance the interest, honor, dignity, and happiness of a free, independent, and virtuous people. In time, they would be joined by such people as Maria Mitchell, Ralph Bunche, and Scott Momaday. If I squint my eyes enough, I can see the souls of the people who have come before us, who have made the discoveries and addressed the challenges of their day, as we have done in our own generation. I know that the generations to come will be making discoveries and meeting challenges that we can’t even conceive today. But they’ll probably also be dealing with challenges that have attended this country since the beginning, bringing them closer to the starting gate than to the finish line. I’m okay with that because if that’s where the struggle and the challenge are, then that’s where the discovery, the triumph, and the joy will be.

Thank you again for the invitation to present some of my work to you this morning and for the indulgence of your time.

Conversation

LAURIE L. PATTON: Thank you. That was an incredible presentation, and thank you for mentioning the Academy at the end. I must be wise because I have surrounded myself with 5,200 members who are smarter than I am. We are in a room full of people who are the top leaders in their fields.

Let’s start our conversation by talking about your history. Your first love was screenwriting but you also loved Steely Dan. Could you tell us how screenwriting and music were formative for you?

DAVID DUNNING: I grew up in a small town in Central Michigan, in Midland, the world headquarters of Dow Chemical. There wasn’t much to do, but I realize that was very important for all of us who were growing up there. We formed our own soccer teams. We formed our own football teams. I was in a mime troupe and did a lot of theater. Other people were playing music and painting. We were just doing, mostly out of sheer boredom. I also watched a lot of television, and I was drawn to it as an art form of storytelling. I began to do screenwriting in my spare time in the evening, essentially to figure out how to do this art form. And I still work at that, studying what’s going on now. Those were my formative years, and they have informed how I do science.

Briefly about Steely Dan. The only radio we had was Top 40, except after midnight, when the local station would switch over to jazz, which was a godsend. Steely Dan is a gateway drug into jazz. I am of the opinion that there are people who despise Steely Dan because their preferences go to punk, and I absolutely appreciate that, but to be honest, Steely Dan doesn’t care what you think. I appreciate that attitude as well.

PATTON: Last year during our Induction weekend, I interviewed scientist André Fenton, a new member, and he talked about his early interests in literature and English. I think there’s something that makes you a creative and energetic scientist that is connected to the love of telling stories.

DUNNING: Yes, I believe that’s true.

PATTON: Here’s a question I’ve been waiting to ask ever since reading your work: What is the difference between saying, “I was subject to the Dunning-Kruger effect,” and saying, “I was arrogant”? There’s seems to be a double curse of the Dunning-Kruger effect.

DUNNING: Well, there is a distinction between vincible ignorance and invincible ignorance. It doesn’t map onto Catholic terms, but it comes close. Often people walk into error that could have been prevented because they failed to do due diligence, and that could be attributed to ignorance. Or it’s a situation in which Dunning-Kruger could occur, such as when you’re doing something that you haven’t done before that contains the unknown unknowns, the situations or risks that you just don’t know about. And that’s when you should seek mentors and talk to other people. That’s vincible ignorance. Now, there is invincible ignorance as well, where no one can know. The world contains so many more multitudes. There is chance, there is luck, and there’s also no way for us to know. You prepare for what you can prepare for. You don’t become obsessive about it. There’s the invincible side of ignorance, and for that, you just prepare for life’s little surprises.

PATTON: It’s interesting because I was thinking about invincible ignorance in the opposite way, which is that you’re happy being ignorant, and it doesn’t matter what corrections you get. What is wonderful about your work is that it’s about the process of knowing. I’ll ask you about expertise and experience in a moment, because there’s a lot of literature about your work that is trying to get at that question. But, before I do that, there is the excitement about getting the first pool shot in even though you’re nervous, or doing the math problem well even though you thought you were really bad at math. I’m thinking about this as an educator.

DUNNING: I teach an undergraduate course on the self, and begin by examining how difficult it is to follow the Oracle of Delphi’s maxim “Know thyself.” I’ve come to learn that the first two weeks of class really depress the students. And so, I do some therapy with them. I tell them the world is the same world that you had before. Everybody faces challenges and survives. We are going to learn more about how to conduct yourself in life, and how to think about things. And when you have that first severe disappointment, and it’s going to happen, it is okay to be disappointed. But it’s important to talk to people. This is how I start preparing them for the future.

PATTON: That’s powerful and it is connected to my next question. How can you maintain the joy in knowing, in learning, and even in making mistakes if you might have overestimated your abilities? I’m thinking about Claude Steele’s work and the idea of internal stereotyping. I’m sure there are gender, racial, and class aspects to this question of confidence and overconfidence. Have you done research on this?

DUNNING: That is a central question, because when people overestimate or underestimate themselves they think that what they’re doing isn’t based on their experience on this quiz or on this task. They think it’s based on these preconceived theories they have about themselves. A lot of the evaluation is top-down. It’s based on what I think about myself. Do I think I’m good at this, or not? It’s not based on the experience.

There are instances in which we see divergences in how people think based on gender or cultural differences, and we’ve done some work on that. When you have a divergence in these preconceived notions of self, then there will be a divergence in how well people have done, even though they’re exactly equal in their skill and the dexterity in what they’re doing.

At Cornell, we did a study in which we gave a pop quiz on science. We know that female students think less of their scientific talent compared to male students. The female and male students did equally well on the quiz. We said to the students, “We are working with the chemistry department on a science Jeopardy quiz show at the end of the semester. Do you want to participate?” The men were 20 percent more likely to say yes, not based on their actual quiz score, but on their preconceived notion of how they thought they had done on the quiz. It was the preconceived notion that influenced their evaluation of how well they had done, which in turn influenced whether or not they volunteered to be on the science show. So, there’s an impact not only on perception, but on choices that follow from that perception.

We did a later set of studies and discovered that these preconceived notions of self were actually interfering with people’s experience of the task. “Did you think it was taking you long to do this task?” “Did you think the terms were esoteric?” “Were you conflicted between the choices?” And their responses were connected to how they thought about themselves.

PATTON: Are you and your team going to do more with that? There seems to be much more to discover and understand.

DUNNING: We were hoping other people would continue these studies, but they haven’t yet. So we may go back and do some more work on this.

PATTON: It seems that a lot of this could be connected in interesting ways to using AI as a coach. As an educator, I’ve seen many students shut down after being told they were overconfident or less skilled than they believed. That criticism devastated them and erased their confidence. There’s a fragility there that is part of being young.

DUNNING: I resonate with the coach model. In fact, I’m doing that right now with my graduate class.

PATTON: Say more.

DUNNING: UMich allows you to bring in an AI tailored to your class, and then you can do with it whatever you want. There’s a researcher at USC who works with the Army, and I’m using his model to create an AI that is, in effect, an assistant coach to what I am doing. I use the AI not to give the students ideas, but to encourage the students to come up with their own ideas. I’ve found in previous experiences that some students will ask the AI, “What should I think? Tell me the answer.” Other students will use the AI creatively to explore possibilities. I want everybody to be that last type of student.

Students diverge greatly in the education that they’re getting, so you have to give students feedback in a way that allows them to understand that it is a process and they are going to improve. The next step is to ask them how they are going to address this weakness in their knowledge. What’s their plan?

In Utah, a few chemistry professors incorporated a weekly feedback quiz into their classes so students could find out what material they weren’t strong in. And then they were asked to come up with a plan to deal with that weakness. It was an incremental process, and it really lowered the percentage of students who failed the class. That’s how you do it.

PATTON: That’s very interesting. As an educator I’ve noticed that if you give students an idea and the tools that they can turn to, even if they’re not using them now, those two things can make a real difference.

DUNNING: I agree.

PATTON: A few more questions before we turn to our Q&A with the audience. What has it been like to live with the Dunning-Kruger effect? In doing some research on your work I found that the Dunning-Kruger effect is itself subject to the Dunning-Kruger effect. In fact, there’s a website in which people think they know what the Dunning-Kruger effect is. What has it been like to live with that and to carry that for twenty-five years?

DUNNING: I truly don’t understand why this thing has stayed viral for twenty-five years. After we did the research, I sat down and said, okay, I have no idea how to follow this up. But now I do. My field has caught up, too. Unfortunately, people misunderstand what the Dunning-Kruger effect is. In an acceptance speech for an award that I received, I said, “Here are four ways in which people misunderstand what the Dunning-Kruger effect is.” I invite you to look for images of the Dunning-Kruger effect on Google, and you’ll be amazed if within the first twenty images, you find one that looks anything like a graph I showed you earlier. I’m intrigued by the idea that public discussions about concepts really involve mistaken and shallow ideas of what the concept really is. But that’s future work.

PATTON: It seems there are all sorts of interesting implications of this for people in leadership positions, when you sometimes have to be a generalist. You’re always a beginner, but in a different way, and you can become overconfident because people treat you as if you know more than you actually do.

DUNNING: That’s right. But I don’t want to dismiss confidence or even overconfidence, because confidence is not something to avoid. Confidence is something to manage. There are times when you want to be confident. If you’re a doctor, and you think you have the right treatment plan for a patient but aren’t 100 percent sure, then your confidence is appropriate because odds are the patient will be better off if they follow what you suggest. Confidence can persuade, but you need to monitor what’s going on. If you’re a doctor, you order blood tests. You do your due diligence, study the problem, and prepare for it.

PATTON: Something that I am very much occupied with and think about for the Academy is the social divide that we feel in America right now, between expertise and experience. In your work, you’ve explained the difference between expertise and experience, where expertise is the capacity to spot falsity. I’m thinking about the study you described when you gave completely made-up concepts to the students in the psychology and law class. I wonder if some of the students were thinking, “I should know this concept because of this class so I’m going to say that I’m familiar with the concept.” For me, I know many Sanskrit words, but there are many more Sanskrit words that I don’t know. So, if someone says, “This Sanskrit word exists,” even if it doesn’t, there’s almost a legitimately scientific and even appropriately hesitant approach to saying, “Yes, it could be a word, even if I don’t happen to recognize it right now.” In those cases, I think there are some really interesting ways in which expertise and the capacity to spot falsity, even at the highest level, are subject to these confidence questions.

DUNNING: Yes, I agree with that.

PATTON: But there is also something powerful about experience. Can experience, too, even if it is not sanctioned expertise, help us spot falsity? I worry about saying that expertise can spot falsity more than experience can, because I feel the social divide between experts and non-experts so keenly in America right now.

DUNNING: What we need to understand is that there is no one thing that is expertise. Experience is expertise. And I would not dismiss that. Whether it’s experience or whether it’s knowledge, true expertise reestablishes the ability to spot falsity and the truth. If you go to experts like doctors, they don’t falsely recognize fake diseases or fake conditions, but undergraduate pre-med students do, for example. It gets complicated because we also have research that shows that it’s good to be the expert, to know when you’re correct about something, but also to be aware of your mistakes. And this is something that we just kept seeing in the data again and again. We actually saw it in other people’s data, but they had missed it because they didn’t look at their graphs. Expertise helps, but it doesn’t lead you to perfection in this task that we refer to as metacognition, which is knowing when you know and knowing when you don’t know. In terms of contrasting expertise and experience, I would argue that there are many different forms of expertise.

PATTON: And what about shame? I think it’s also part of the learning process. Let’s turn now to questions from our audience.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You touched on this briefly, but I’m curious about ignorance. Stuart Firestein wrote a book on the pursuit of ignorance in science, about the humility of scientists in acknowledging what they do and do not know. But there’s also ignorance at a community level. I wonder about the interplay of personal ignorance and community ignorance.

DUNNING: I’ve been trying to encourage students to study this because one way to alleviate ignorance is to have people interact with one another. We are currently doing experiments in which participants answer questions, and we’ve found that they’re confident both in their right answers and in their wrong answers. Another person will look at the responses, and they’ll spot the mistakes. But that fails at the community level if there’s a sense of conventional wisdom. For example, in the sciences, there’s a certain way to define terms and to accept evidence. I might teach a class in psychology and law about how behavioral scientists operate in terms of what is evidence and what is a legitimate conclusion. But how the law defines evidence and what’s a legitimate conclusion are different. There’s a chasm. Does that lead to communities of knowledge that also suffer from ignorance? It’s a big topic that is absolutely worthy of study.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: When I was a kid, I read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and I loved it. It was a terrific book, but I think I missed the point. When I got older, I saw something else in the book that I think is very relevant. The book analyzes what happens if you firmly believe in something and you’re confronted with evidence that shows that what you believe in is in fact completely wrong. The question is, what do you do, and how do you address that? What the book shows is that you do not give up on what you believe in, but, rather, you complicate your belief system in order to admit a possible explanation that’s contradicting your belief system. The book is full of examples of that, and I think it should be required reading for anybody who is a scientist and talks to the public.

DUNNING: I think it should be required reading for social psychologists as well. What you’re describing is called cognitive dissonance, and it’s one of the most powerful engines of belief permanence. It was at play in the experiment in which people who received negative feedback about their emotional intelligence said they didn’t need the book that was being offered to them at half price. There is this layer in which you don’t need motivation. It’s just the way that we think. But the dissonance level does exist and it sounds like it’s powerfully illustrated by Mark Twain.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You humorously noted that people shouldn’t ask you about where your gaps are. They should ask your friends, who are unlikely to tell you, but they might tell them. You also said that one of the ways to deal with the topic is to surround yourself with other people who have other ideas, but those two things seem to conflict. If your friends aren’t likely to tell you, but you’re the one who needs to know, then how are you and others being measured? What have you measured about leaders and the types of interactions or the types of people that they should surround themselves with?

DUNNING: I’ll use the terms honesty and bluntness. Other cultures are very good at being honest and blunt, but we aren’t so good at that in the United States. And it’s evident in personal relationships, in families, among friends, and even in business. We’re not very good at giving feedback effectively and receiving that feedback effectively. I wish there was more instruction on this. There was a classic review of feedback programs in business that showed that about 40 percent of feedback programs actually demotivated employees. So I wish we were more effective in giving and in receiving feedback.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: In interviews, when you’re looking for people who are adaptable and resilient, what interview question would you ask to discover if the candidate has those qualities?

DUNNING: I’m going to suggest something that you’re probably already asking: “Can you describe a mistake you made in which you learned something?” You’ll know the worth of the answer once you start hearing their responses.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What do we do when people overestimate their knowledge and end up being hostile to expertise? I’m thinking about COVID-19 and vaccines.

DUNNING: The issue isn’t information or knowledge. It’s a matter of trust. Experts have to establish who they are and that they are humans like you. We need to show the humanity of science. I think the technical details and the information are actually secondary, but I realize that everyone may not agree with me.

PATTON: Thank you, David, for your presentation and for this interesting and lively conversation. I would like to extend my congratulations again to all of our new inductees. We are glad to have you as members of this Academy and we look forward to working with you. We have discovered in the last eight months, as we struggle with the challenges in our country, that people are turning to the Academy to lead. Our independence matters. Our longevity gives people confidence. Our practice of convening gives people resilience. And our commitment to nonpartisanship gives people hope. This really is a moment for the Academy to lead.

© 2026 by David Dunning

To view or listen to the presentation, visit the Academy’s website.