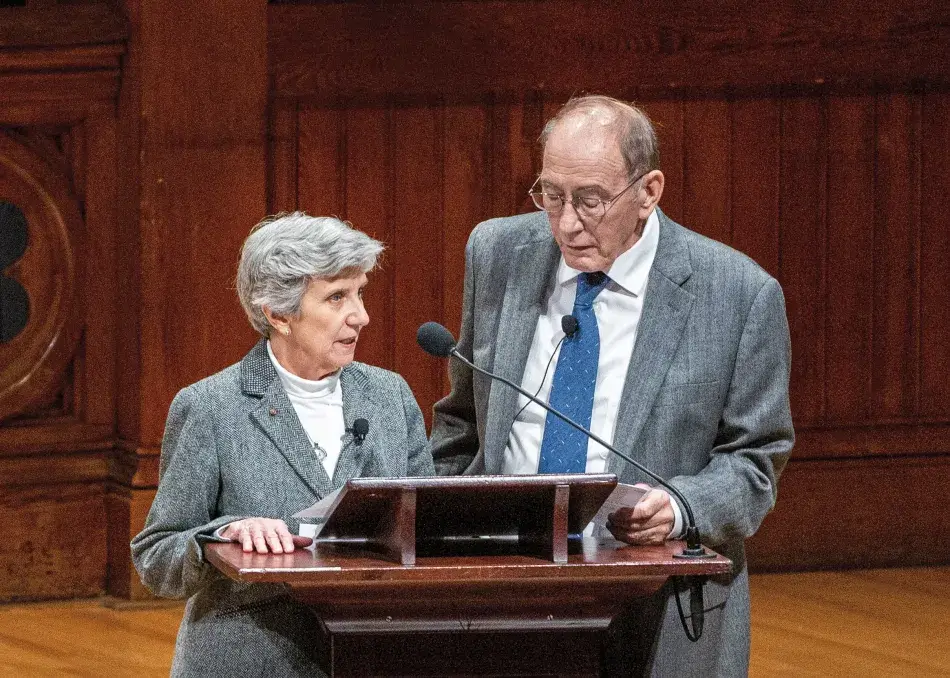

Climate change, soil erosion, human rights, Indigenous peoples, and “fixing” our democracy — the class speakers at the 2019 Induction Ceremony addressed major issues facing the world today, with calls to action and calls for change. Following a reading from the letters of John and Abigail Adams by humanitarian Jane Olson and attorney Ronald Olson, newly elected members spoke passionately about their life’s work. The ceremony featured presentations from paleoclimatologists Ellen Mosley-Thompson and Lonnie G. Thompson; microbiologist Jo Handelsman; former United Nations diplomat Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein; historian Margaret Jacobs; and lawyer and advocate Sherrilyn Ifill. An edited version of their presentations follows.

2083rd Stated Meeting | October 12, 2019 | Cambridge, MA

Lonnie G. Thompson is Distinguished University Professor in the School of Earth Sciences and a Senior Research Scientist in the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at The Ohio State University. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2019.

It is an honor for us to address this distinguished assembly of passionate and accomplished people on behalf of Class I, the Mathematical and Physical Sciences.

The twenty-first century faces numerous challenges, and one of the greatest is dealing with unprecedented, global-scale environmental changes. Virtually everything depends on how Earth’s climate fluctuates and how we choose to mitigate and adapt to it. Our national and global economies, agriculture, quality of life, societal stability, and the availability of food and safe water, among other things, depend on a relatively stable climate. Unfortunately, this critical issue gains prominence in the American public eye only during and in the wake of extreme events such as deadly heat waves and catastrophic hurricanes that affect the U.S. mainland. After the emergency has passed and the task of recovery and rebuilding are well underway, the conversation about climate change returns to mere background noise in the media and public discourse. Our lack of attention to climate-related human tragedies in other countries arises from the belief that what affects people far away will not bother us due to the advantage of distance.

However, where climate is concerned there is no such thing as “far away.” Climate does not respect national borders or cultural or ethnic differences. Because of hemispheric and even planetary atmospheric teleconnections, weather that affects regions on one side of the world generally affects those living elsewhere. Polar and alpine ice is melting at unprecedented rates and raising global sea level, which will continue to accelerate and result in marine encroachment on coastal cities and wetlands. The retreat of the Arctic sea ice in summer is altering atmospheric circulation patterns and bringing unusual and often extreme weather to the mid-latitudes, including our nation’s agricultural belt. Adverse climate conditions in poor nations are already contributing to mass migration to wealthier countries, sometimes resulting in strident governmental reactions. The situation will become more critical in the coming decades as mountain glaciers in developing areas such as the Andean and South Asian regions retreat and eventually disappear, resulting in water resource, agricultural, and economic stresses that can exacerbate political unrest. The increases in the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide and methane, have paralleled the growth in world population and economic development. Evidence from Antarctic ice cores tells us that current greenhouse gas concentrations are higher now than at any other time in the last eight hundred thousand years.The concept that human activities are closely connected to the environment is not new. The naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who lived two hundred years ago, was the first to make this connection. He recognized the effects that environmental degradation would have on future generations. When von Humboldt was undertaking scientific expeditions throughout the world in the early nineteenth century, world population was around 1 billion. The environmental effects of the Industrial Revolution were restricted to Northern Europe and small regions of Eastern North America. Today, Earth is home to over 7.5 billion people, with over 80 percent living in developing countries that increasingly rely on carbon-based fuels and are developing their economies at the expense of the environment. Not only as citizens of nations, but as citizens of Earth, we must face and overcome the challenges presented by our changing climate. As the world’s population and our technology to exploit natural resources continue to grow, the need to understand human influences on the processes driving climate change and environmental degradation are more critical now than ever.

To meet that need we must redouble our efforts to train and support our aspiring scientists, ensure they have opportunities to observe their world first-hand through field experiences, and encourage them to develop the communication skills needed to instill public trust in the scientific enterprise. Sherwood Rowland, Nobel laureate in environmental chemistry, who is best known for his contributions to discovering the chemical compounds destroying the ozone layer, asked a poignant question: “What’s the use of having developed a science well enough to make predictions if, in the end, all we’re willing to do is stand around and wait for them to come true?” The public and the private sectors must invest in the development and implementation of renewable energy sources at the expense of carbon-based energy.

In the past, nations have put aside cultural, political, and religious differences to mitigate threats to the well-being of humanity. For example, during the world wars of the twentieth century, adversaries formed alliances to defeat aggression on several continents. Although the effects of a changing climate are manifested more gradually, we are facing a type of “war” in which all nations, including adversaries, must cooperate for the ultimate welfare of existing and future generations. Many countries that are politically and economically at odds are nevertheless collaborating on climate research. In our research program, for example, over the past forty years we have drilled ice cores from glaciers and ice sheets around the world. This was possible only because international teams of scientists and mountaineers were willing to endure harsh living and working conditions, lasting from weeks to months, in very remote regions far from the basic comforts we often take for granted. We hope that the global community will ultimately work together to diminish the causes of the current anthropogenic climate changes and to mitigate their worst impacts. Our fear is that if we delay, mitigation will no longer be our best option and our only choices will be adaptation and suffering. Human actions have created the unfolding climatic and environmental crises, but we have the opportunity to recognize the reality of our current situation and work together to change our habits of energy production and consumption and thereby put Earth on a more healthy and sustainable course.

© 2020 by Ellen Mosley-Thompson and Lonnie G. Thompson

For the final three years of the Obama administration I served as one of President Obama’s science advisors. I advised the president on issues as diverse as precision medicine, gene editing, forensic science, Ebola virus, and STEM education. Some of the topics were of his choosing, some mine. Some were rapid responses to emerging world problems. In those three exciting years, I wrote many memos to the president informing him about issues that are close to my heart and many that needed to be closer to our nation’s heart.

One of my greatest regrets about my time in the White House was that the only memo that I was never able to send to the president was about what may be the most pressing issue of our time – loss of soil. I wrote a memo, but could never penetrate the phalanx surrounding the president with this one. I was blocked at every turn. So I vowed to make the subject of that memo the top priority of the rest of my career as a scientist. In that capacity, I would like to read to you now a memo that I might have sent to President Obama.

Dear Mr. President:

I write to alert you to the soil crisis that threatens soil across the United States and many other regions of the world. Soil is a precious resource that underpins the health of Earth and its civilizations. Yes, we’re talking about soil – we also call it earth and dirt; suelo in Spanish; Łeezh in Navajo; adama in Hebrew; talaj in Hungarian; udongo in Swahili; and dojo in Japanese.

Whatever we call it, it is the product of millennia of biological and physical forces acting on Earth’s crust. Pulverized geologic material is weathered and mixes with dead and live plant, animal, and microbial materials and the chemicals released by their decomposition. These are the starting materials of soil. Water percolates through, air fills empty pockets, plants penetrate, animals burrow, and microbes turn the crank of nutrient cycles. Over hundreds of years, soil is enriched and deepened by these processes to produce the fertile material we know as topsoil on Earth today.

Soil supports many essential processes. Familiar to most people is its role in agriculture and forestry, where soil forms the substrate in which plants grow. But soil’s profound impact on Earth extends far beyond plant growth. All organisms depend on soil for clean water – in fact, soil serves as the largest water filter on Earth. Soil microorganisms manage the nitrogen, phosphorus, and water cycles, and soil serves as the largest repository for carbon on Earth – it contains three times the amount of carbon in all plants combined and twice the amount in Earth’s atmosphere. Practical uses of soil abound. It is used by people for constructing buildings, roadbeds, and pottery and is the source of drugs used in traditional and modern medicine, including three-fourths of the antibiotics used in clinical medicine today. It contains the most biologically diverse environment on Earth, gifting us with the potential of great discovery and great beauty.

Now soil is under threat. It is being eroded and degraded rapidly, and those processes are likely to accelerate with the projected climate changes that produce more frequent heavy precipitation events. The United States and many other countries are eroding soil ten to one hundred times faster than it is produced. By some projections, the United States will run out of soil on much of its sloped agricultural land by the end of the twenty-first century, but many regions will be barren in the next ten to twenty years. Although the exact endpoint is unclear, it is abundantly clear that the current trend is not sustainable – if it continues, we will run out of soil. The endpoint will vary across the landscape depending upon the slope of land, weather events, and farming practices. The Midwest has already lost half of its soil since 1850, and in many locations in Iowa, subsoil is visible where all the topsoil has eroded. With these trends, food production will confront unprecedented challenges as erosion intensifies.

There is a long history of civilizations collapsing because of soil erosion. The population of Easter Island declined from fourteen thousand to two thousand after their soil eroded from steep mountainsides into the ocean, leaving the island without agricultural production. Similar examples of societies that have over-tilled their soil, which then eroded along with the ability to produce food, abound in regions of China, Africa, and the United States. The good news is that sufficient knowledge is in hand to diminish or even halt soil erosion with relatively little short-term cost and substantial long-term savings. Agricultural practices such as no-till planting, use of cover crops, and interplanting crops such as corn with deep-rooted prairie plants comprise the trilogy of proven methods to prevent erosion and rebuild soil health.

These farming practices would enhance soil carbon storage, thereby reducing greenhouse gases. In the Paris climate talks of 2016, there was a proposal to increase soil carbon worldwide by 0.4 percent, which would be sufficient to compensate for the projected increased carbon emissions, thereby keeping atmospheric carbon at its current levels.

There are several policies that your administration could implement that would encourage farmers to adopt soil-protective practices and build up soil carbon. The administration could galvanize consumers to participate in a movement toward a “soil safe” label for food that would be based on certification of farming practices that build rather than destroy soil. The administration could partner with farmers, environmental groups, agrichemical companies, food retailers, and consumers to develop criteria for certification and then guide its implementation in a manner that makes changes in farming practices financially feasible for the producers.

Mr. President, thank you for your tireless work on behalf of Earth’s health. I deliver to you a challenging problem, but one that can be quickly solved. All we need is the will, and we dare not lack that will or our civilization as we know it will not be sustained.

© 2020 by Jo Handelsman

Dear friends, I am honored to be delivering the following statement on behalf of Class III, the Social and Behavioral Sciences, and before this magnificent Academy with so many of the world’s most accomplished and esteemed scholars. While I am very grateful to the Academy, there’s obviously been some sort of terrible mistake when it comes to my induction – not only am I not a career academic, but the last time I published anything scholarly was a long time ago! I have a receipt here from one rather upset fellow named Claus who, using the most disrespectful language – replete with expletives – wrote to me in 1802. I am suspending reality for a moment! He writes, “you so-and-so . . . ,” he was quite drunk, “you dirty dog,” now that is the PG part, “. . . you still owe us, my family, for printing services rendered by great grandpapa Gutenberg!”

So you see, dear friends, it was a long time ago when I last published anything! Now before the bailiff or police officer throws me off the stage for willful impersonation of someone who deserves to be here, and before I am disowned by Class III, let me offer a few thoughts if I may, capped by an appeal to the Academy.

I have come to realize, over time, that most people don’t know what their rights are, or even what human rights are.

Yet however they view them, most people seem to think human rights exist as some sort of moral post-it note or a feel good – almost a decorative annex to the human experience. If not whimsically simple, then human rights are seen from the other extreme, as being overly technical, overly legal, ultimately a weakish creation. And overall, the layperson’s understanding of human rights is best captured by the iconic image of Eleanor Roosevelt holding up the Universal Declaration, or seeing photos on some UNICEF poster of primary schoolchildren reading its articles. And if you are better informed, then a few desks tucked away in a human rights center – usually an office found within the small number of law faculties that house them – is academia’s way of acknowledging the presence of this awkward, interdisciplinary, almost orphan-like subject matter we call Human Rights.Human Rights. Two words that often gate-crash into a reader’s field of vision when they are scanning the penultimate paragraph in a report issued by the UN Secretary-General. And that is the good news – at the very least, the two words are there in the UN report.

But sadly, they are barely detectable within the broader expanse of academic scholarship, especially with respect to the social sciences: namely, economics, development economics, political science. Now don’t get me going about business or corporate literature – for goodness sake, don’t mention these two words. We will upset China or some of the Arab states . . .we will lose our funding, our readership, our market, or some investment or research opportunity. Better to slice human rights up (after all, the perforations already exist) and speak of them in part only – civil rights, women’s rights, LGBTQI rights. And if this is still beyond what our nerves can bear – too threatening to others – euphemisms work well too: shared values, harmony, inclusive economies, gender mainstreaming, and so on; but not those two words. . . . Voldemort would be so proud!

Upset? Why should the Arab states and the like be so upset? Human rights mean nothing to most of the lay public internationally and to many of my academic colleagues who ought to know, they actually know very little about human rights. Tragically, many could not be bothered to learn about them because they are not humanitarian principles as is so often presumed.

And yet . . . and yet . . .

A few weeks ago, the head of a leading IT company argued with me that only the human rights community – not the most powerful of the European governments – could exert the higher forms of pressure on Silicon Valley that are needed to bring AI into greater alignment with human rights law.

What? What epitome of weakness! The spindly thing, spindly when compared to France and Germany, spindly when compared to corporate power, with all their CEOs – their eyebrows furrowed – extolling shareholder value or their fiduciary responsibilities, respecting only (or so it would seem) some retired military four-star officers, speaking geopolitics to them.

And yet it is the human rights community, the human rights NGOs, with their minuscule budgets – the Frodos of this world – that must take on the big five with their combined annual revenues of many hundreds of billions of dollars, if not trillions, and make them change.

So how does one make any sense of this?

Dear friends, human rights are not boutique, nor are they weak, marginal, or even values. They are a set of interlocking treaties (nine of them) codifying all manner of rights – from women’s rights, to child rights, to the rights of persons with disabilities – while establishing clear prohibitions for the violation of a specific number of these rights, including torture, enforced disappearances, and racial and gender discrimination.

They impose legal obligations on those governments that accede to them and establish an international standard that ought to be met by the rest. In sum, they form an injunction built on three basic expectations: that a government will not discriminate against any individual on prohibited grounds; that (correspondingly) a government will not deprive that individual of social and legal protections and services; and that a government will not govern by fear.

And while elections are a key prop for the legitimacy of governments – a legitimacy conferred on them by their constitutions – only when those governments then actually serve their people can that legitimacy be properly certified. When a government fails to do that and defaults on and violates its human rights obligations toward its people, it submits its legitimacy not just to their scrutiny and doubt, but also to that of the wider international community. And that, my friends, is why human rights are politically so immensely powerful! They delegitimize as easily as they legitimize, and the authoritarian-minded leaders of the world simply do not like that, and hence do not want them.

The violators of human rights are challenging the universal human rights framework in a manner not seen since 1948 – human rights are the antonym for what they, with their thinner agendas, stand for. Though human rights proponents may be few in number, they are pushing back everywhere: the people of Hong Kong are in the ring; so is the NAACP; the Democrats on the Hill are in it too; the people of Ecuador are protesting daily; Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad are on the front lines; Agnès Callamard, the extraordinary UN Special Rapporteur, is simply heroic; so too is her colleague Philip Alston; and Maria Ressa is also fighting. Greta Thunberg is utterly phenomenal too. So many other extraordinarily brave people are shaking off their fear – from Poland to Egypt to Venezuela – demanding their rights, the rights of others, the human rights of all, and, almost always, without wanting to hurt anyone.

Notwithstanding what we heard this morning about nonpartisanship, I submit to you that this is not the time for it! I appeal to the Academy to join in, and do so forcefully, to be more involved: to use its power and influence in placing human rights center stage, where they must be – academically, politically, culturally. For many of us here who are tenured in the United States, we enjoy both job security and the protections of the First Amendment. This is an opportunity for us to make a mark. We must do so and defend the universal rights agenda where we can because our lives and the lives of those we hold so dear – indeed all that we have created together as human beings – rest on their being upheld.

With that, I am now quite ready to be thrown off the stage!

© 2020 by Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein

Thank you for welcoming me into the Academy, and for asking me to speak on behalf of Class IV, the Humanities and Arts. I am truly honored to speak before you today, at this historic place and institution, and on the homelands of the Wampanoag people.

In a culture consumed with the present and even more so with the future, we historians may seem as antiquated as the subjects we study. We get a little frisson when we enter a library. We swoon at the musty smell of the archive. A positive thrill electrifies us when we stand on the site of a historic event. We can sense the past alive in the present.

In our current attention economy, history may seem irrelevant. It’s so . . . yesterday. But recovering, acknowledging, and learning from our history – a key task of the humanities – may be just what we need to truly live well with one another, now and in the future.

June 10, 2018: A farm in Nebraska. It’s hot, humid, and hazy with an insistent wind. This likely fits your image of our state. The farm’s owners, Art and Helen Tanderup, might confirm your stereotypes, too. They are White and in their sixties. Art is portly, seemingly gruff. Helen exudes stand-by-your-man farm wife. This homestead has been in Helen’s family ever since the late nineteenth century.

But this isn’t Little House on the Prairie. There are Indians everywhere: Poncas, Omahas, Winnebagos. They ride up to the Tanderups’ farm in fully decked-out pickups. They tumble out of their trucks in shorts, jeans, and flip-flops. Some of the women wear handmade calico skirts ringed with ribbons. There are non-Indians, too, wearing baseball caps, cargo shorts, Birkenstocks. Kids turn cartwheels on the grass; their grandparents lounge on folding chairs.

The hugs and the smiles make clear that these people have known each other for a while. They had originally come together in 2013 to oppose a transnational oil pipeline that would bisect the Tanderups’ farm and the homelands of the Poncas. Then, something else happened. Political alliances grew into personal friendships. And these blossomed into a new tradition: the planting of sacred Ponca corn on the Tanderups’ farm every year. These events led to this historic summer day.

The Tanderups are holding a ceremony with two leaders of the Ponca nations of Oklahoma and Nebraska. At a similar gathering, 160 years ago, Ponca leaders had signed over thousands of acres of their homelands in Nebraska to the U.S. government in return for a small reservation. This land was redistributed to homesteaders like Helen’s ancestors. Despite this treaty, the government decided to relocate the Poncas to Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. In the 1870s, at the point of bayonets, the military forced the Poncas to march six hundred miles to a foreign land. Today, the Tanderups are signing a kind of reverse treaty that returns ten acres of their farm to the Poncas.

During the ceremony, Art says, “it can never make what went wrong right, but it can show how we feel about this [injustice].” As Art and Helen sign the deed to transfer the land, Casey Camp-Horinek, of the Ponca tribe of Oklahoma, breaks down. When she can speak again, she says, “This day our Mother the Earth sustained us, and gave us reason to live.” She signs the deed and passes it to Larry Wright, Jr., chairman of the Ponca tribe of Nebraska. He declares, “This means a lot. To be able to sit here as partners, to come together out of the goodness of your heart[s] and undo what the federal government did.”

This ceremony encompasses the components of restorative justice. Ponca leaders told of their history, the mistreatment they had suffered at the hands of settlers. The Tanderups honestly confronted this history. They took responsibility for these past harms, as witnesses looked on. Then they offered redress.

This gesture of personal truth and reconciliation may seem like a quaint throwback to the early civil rights era. Yet in a global context, it is not the Tanderups and the Poncas who are out-of-touch; it is the United States. New Zealand created a tribunal to respond to the grievances of the Maoris – in 1975. The Canadian and Australian governments both carried out extensive inquiries into the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families. In 2008, both nations issued official apologies for this heartless abuse.

But in the United States, when faced with the cruelties of our history, most of us in the White population retreat into denial. We can hardly imagine that any person could act out of moral responsibility, not crude self-interest. But there are a few, like the Tanderups, who step up and face the truth of history and accept accountability. And then they go one step further – they take action to make amends. The cynics think that those who acknowledge this history have a lot to lose. But Art says, “it’s something that makes our hearts feel good.”

Mekasi Horinek, a Ponca, played his drum and sang at the end of the ceremony that summer day in Nebraska. Just before he began, he said, “over the past 5 years [Art and I] got to spend time with each other and know each other’s families. To know each other’s hearts. And I know that what he’s doing is from his heart. From my heart I just want to say I love you, my friend.”

Facing our history, together, is not an exercise in shaming. It is an act of respect, integrity, and interconnectedness. The Poncas and the Tanderups show us just how much we have to gain by confronting and learning from our history, not denying and evading it. They teach us, too, that anyone – and everyone – can engage in acts of truth and reconciliation. And that it may be these small gestures that have the greatest power to heal the wounds of history. The humanities, it turns out, have a lot to teach us about restoring our humanity.

© 2020 by Margaret D. Jacob

I really cannot express in words what an honor it is to be inducted into this august group and to have the opportunity to speak with you today on behalf of Class V: Public Affairs, Business, and Administration. When I agreed to speak for our class, the Academy team very kindly sent me the remarks made by class speakers over the last four years, which I made the mistake of reading. So impressive. And intimidating.

They were all amazing, but I found that I couldn’t quite shake the opening from Walter Isaacson’s wonderful talk for this class in 2016. He began his remarks with a stark assessment: “The Internet,” he said, “is broken. We broke it. We allowed it to corrode, and now we have to fix it.”

And so I’d like to paraphrase Mr. Isaacson’s opening and frame my remarks around the following thesis: “Our democracy is broken. We broke it. We allowed it to corrode, and now we have to fix it.”

I realize that this is a rather sober opening for the final remarks of the day. But I don’t mean to be discouraging. In fact, I want very much to encourage us. Because what I want to talk with you about today is how we confront what I believe to be the question that plagues my every waking and sometimes sleeping moment: What is our responsibility? What is the responsibility of the citizen when her democracy is broken?

Well, I’ve already cribbed the answer from Walter Isaacson: we must “fix it.” But what does it mean to “fix” our fractured democracy? Well I want to suggest that the fix requires something more than simply gluing the jagged, imperfect, fundamentally flawed pieces of our democracy back together in a semblance of integrity and coherence.

Because our democracy is not newly broken. Those of us who do the work of civil rights – work that at its core requires us to face without flinching the deep cracks and fissures in our democracy – we knew that our democracy is broken. Many of us tried to sound the alarm. We spoke about voter suppression and gerrymanders and out-of-control wealth inequality. We sounded the alarm about a culture of cruelty, about the decimation of public life, and the denigration of public goods in our country. These fissures have now become full-on fractures. And so the task before us is not a simple patch job.

And this is the opportunity I see in this difficult moment in our country. We have the opportunity to dig deep and to marshal our ambition and courage to reimagine what we will need to strengthen and undergird a better democracy than the one whose loss so many of us now lament. And this will require us to embrace a newly invigorated sense of our own obligations and responsibilities as citizens to build and maintain democratic institutions, ideals, and values.

It will not surprise you that for inspiration for this daunting task before us, I turn to the powerful example of ordinary people who took on the work of repairing a broken democracy, and created a new America – one that could produce the diversity and dynamic mosaic of esteemed individuals in this room today. Their courage made the trajectory of my life possible – from the youngest of ten children in Queens to standing at this podium today. What moves me most about the group of mid-twentieth-century democracy builders – these civil rights lawyers who executed a decades-long legal strategy to end segregation – legal apartheid – in this country is that they embarked on this ambitious, often dangerous course without a blueprint. But American democracy was broken, and they knew it. Segregation – nearly a hundred years after the end of the Civil War – was designed to permanently brand Black people in our country with the mark of inferiority and to render us as permanent second-class citizens. It was an expression of White supremacy as powerful and damning as slavery itself. So when Thurgood Marshall and the team at the Legal Defense Fund created a plan to challenge it, they knew they were seeking to dismantle what had been a core feature of American identity – a corrosive and toxic perversion of democracy, but one to which millions of White Americans and almost every institution of American government were fervently committed.

To do this they had to trust in a strategic vision premised on values of equality and justice. They could not become discouraged by loss (and there were losses). They themselves, as African Americans or Jews, were often in peril as they worked on their cases in the South. Their dignity was often challenged in ways great and small. And they had to work past it and through it to meet their goal.

At the end of the first day of the trial in his suit challenging the exclusion of Black students from the University of Oklahoma Law School in 1947, Thurgood Marshall and his client Ada Sipuel talked about how hungry they were. Marshall had prepared meticulously for the trial. But he hadn’t prepared for the fact that he and Ms. Sipuel, as African Americans, would not be permitted to eat in the cafeteria at the federal courthouse. According to Sipuel, Marshall remarked to her as he packed up his briefcase and they prepared to leave the courtroom, “Tomorrow, I’ll try the case and you bring the bologna sandwiches.”

Individuals like Marshall and Constance Baker Motley and Jack Greenberg are the lawyers who inspire me and the LDF staff – especially now.

But it wasn’t only them. There were others who saw the brokenness of our democracy and were determined to use their skills, their assets, their resources – wherever they were in business, in the academy, in education, in their homes and churches and temples – to contribute to the transformation of our democracy.

These individuals, and countless others, worked in a relatively few short years to help transform this country – building a set of norms and policies and narratives that became part of how we came to define our national character. What they successfully created did not benefit a small group of Americans who were treated unjustly. The strengthening of America’s commitment to principles of equality and justice benefitted the entire country.

We too often fail to recognize, for example, how the successes of the Civil Rights Movement strengthened America’s geopolitical power and influence in the Cold War – a war often fought in surrogate third countries, where the image of America as a place of expanding equality and opportunity had powerful currency. Presidents Truman and Eisenhower knew this. I commend to you both Mary Dudziak’s book Cold War Civil Rights and the scholarly work of civil rights lawyer Derrick Bell, who powerfully document this reality.

This country owes a great debt to those who marched, and sacrificed, and endured prison, and died to give this country the opportunity to prove itself better than our foes in the Cold War.

Indeed the historical record of this country demonstrates that whenever America expands the reach of equality and provides greater opportunity for those on the bottom, the entire country benefits.

What better example can there be than the ratification of 14th Amendment of our Constitution in 1868. The opening provision of the amendment is pure democratic genius: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and the State wherein they reside.”

The radical framers who shaped the provision we now call “birthright citizenship” designed it to ensure that newly freed slaves and other Blacks would become full and equal citizens of this country – a status that was stripped away by the Supreme Court’s disastrous decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857. But that provision – designed to protect citizenship for people like me – ensured that many of your great-grandparents and parents could travel to this country and, in one generation, fold their family into full American citizenship. They didn’t need to be wealthy, literate, well-connected, or beautiful. They just had to be here and become naturalized. Their children born here became immediate citizens. This provision of the 14th Amendment made possible the widely accepted concept of America as a “nation of immigrants.” However incomplete that description of our country (slaves after all were not voluntary immigrants), the power of this framing has for more than a hundred years defined the unique and, until recently, widely admired experiment of twentieth- and twenty-first-century America.

Do you see it? The provision was created for people who look like me, but it bestowed full citizenship on more White Americans and secured the national legitimacy of more White immigrant families than any other provision of the Constitution.

And so, to “fix” our democracy, we should remember that there is a guaranteed dividend when we strengthen the guarantees of equality and justice for those at the bottom. So let’s start there.

We are now called to be as ambitious and courageous as those framers of the 14th Amendment who rebuilt American democracy at the end of the Civil War, and those civil rights pioneers who remade American democracy yet again in the middle of the twentieth century. It’s time to rebuild again. The good news is that there are hundreds of us here and thousands, millions, tens of millions more around the country who believe in the building blocks that make a democracy strong – we believe in facts, truth, transparency, dissent, art, science, ethics, opportunity, equality, the rule of law, and justice.

And now as we are confronted with the fragility of our democracy, we – the citizens – must be strong. Our responsibility as citizens requires more than just showing up on election day. We now know that our democracy needs us to put on our hard hats and get to the difficult work of reshaping, reframing, and remolding the very foundations of our democracy. We shouldn’t settle for spackle and a fresh coat of paint. We need a re-imagined capitalism. A redefined sense of corporate responsibility, not only to shareholders, but to democratic ideals and values. A truly transformed vision of criminal justice. A lasting commitment to the arts and humanities. An education system that really provides the foundation for citizenship. A reconfigured system of elections and politics that promotes true and equitable representation. A new commitment to facts and truth and public goods.

At the conclusion of his 2016 speech Walter Isaacson listed the possibilities of what we might gain by “fixing” the Internet. He ended with “the possibility of a more civil discourse.” For the fixing of our democracy – which, by the way, is not unrelated to fixing the Internet – the possibilities are infinitely more ambitious and potentially enduring. And the stakes are too high to even contemplate failure.

© 2020 by Sherrilyn Ifil

To view or listen to the presentations, visit www.amacad.org/induction2019.