2107th Stated Meeting | September 9, 2022 | Klarman Hall, Harvard Business School | David M. Rubenstein Lecture

The opening program of the 2022 Induction weekend featured a conversation between David M. Rubenstein, Co-Founder and Co-Chairman of The Carlyle Group, and cellist Yo-Yo Ma that explored the meaning and honor of Academy membership, the power and universality of music, and the importance of the arts, culture, and education, among other topics. An edited version of their conversation follows.

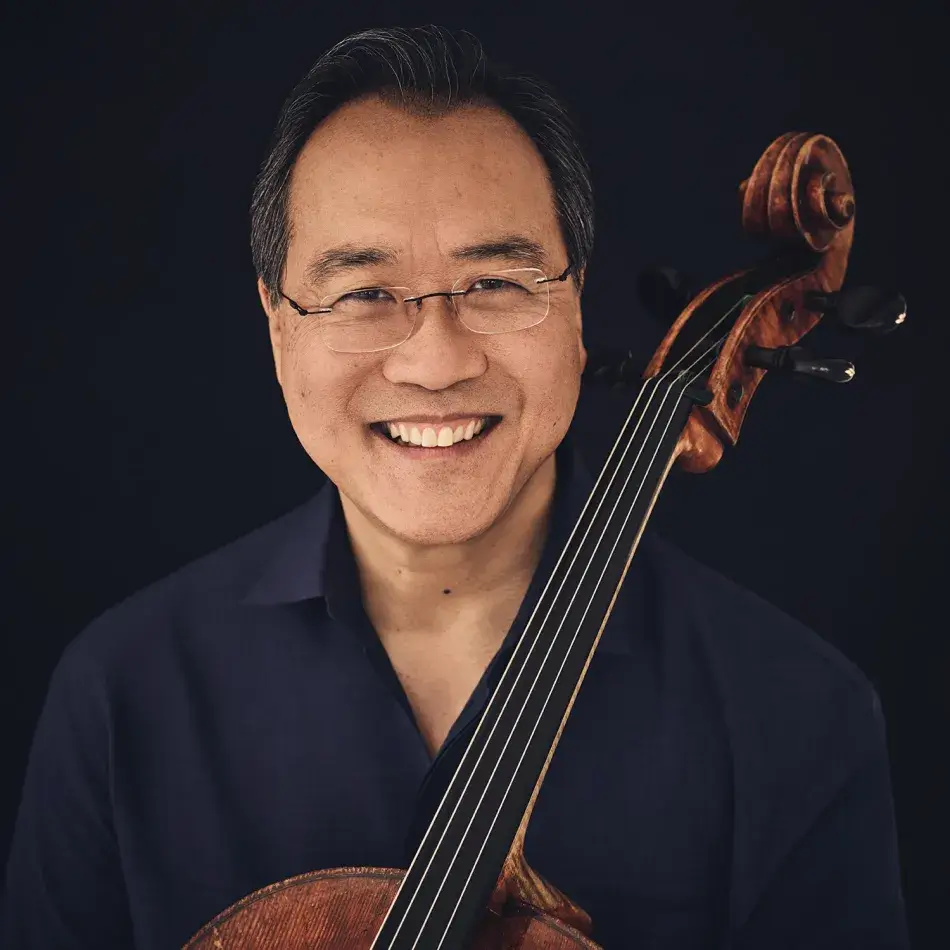

Yo-Yo Ma’s multifaceted career, as both a performing artist and a partner with communities and institutions from Chicago to Guangzhou that develop programs that advocate for a more human-centered world, continues his lifelong commitment to stretching the boundaries of genre and tradition to explore how music not only expresses and creates meaning, but also helps us to imagine and build a stronger society and a better future. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1993.

DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN: It is great to see you. Thank you for joining me in a conversation this evening. Do you remember what your reaction was when you were first told that you had been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences? Did you wonder how you got in?

YO-YO MA: I thought it was a great honor. One of the reasons I went to college was to get a liberal arts education, and I thought, my goodness, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences – that’s exactly where our country should be. The arts and sciences are part of natural philosophy, which was what we had when our country started. I was elated when I was elected, and I am elated today to be here with you and with the new members of the Academy.

RUBENSTEIN: Let’s talk a little about the early part of your life, and how you became such a well-known and world-renowned cellist. You were born in Paris?

MA: I was, at least that is what I have been told.

RUBENSTEIN: And your father was a music teacher?

MA: He was a musician, and he later became a teacher. But he was always a teacher, and certainly he was my teacher.

RUBENSTEIN: Why did you leave Paris to come to the United States? Did your father get a job here?

MA: They were looking for a music teacher at a school in New York, and that’s how we came to the United States.

RUBENSTEIN: What was your name at birth? If I’m correct, it was something other than Yo-Yo.

MA: I think it was David.

RUBENSTEIN: Was it perhaps Ernest?

MA: Actually, my name is a cultural combination. Every day in the French calendar has a saint’s name assigned to it. The fact that I was born on October 7 was important. But it’s also important to note that in more recent Chinese tradition, a lot of babies are not named until they are a month old, because of infant mortality. So, November 7th was Fête Ernest, and that became my French name.

RUBENSTEIN: How old were you when your parents brought you here?

MA: I was seven years old.

RUBENSTEIN: Did you speak English fluently?

MA: Just like right now, no, of course not.

RUBENSTEIN: At what age did you take up the cello?

MA: I was four years old. I have a sister who is four years older, and she played the violin. So, I started the violin at age two, and I played badly. Like a cat screaming, that was what it was like. My parents thought I wasn’t talented. And I should have kept that thing going, because then who knows what I would have become. I might have gone into . . .

RUBENSTEIN: Private equity?

MA: Yes, private equity.

RUBENSTEIN: The cello is a big instrument, and you were only four years old. How did you lug something that size around? Or did they have a smaller version for four-year-olds?

MA: Yes, they had a 16 size. But since I couldn’t go into private equity at age four, I wanted to play the largest instrument. Size is important to a four-year-old, and I had my sights set on something much bigger: the double bass. Obviously, I couldn’t handle that, so I downsized.

RUBENSTEIN: You downsized to the cello?

MA: That’s correct.

RUBENSTEIN: Some people may not remember this, but when the Kennedy Center was first established, before President Kennedy was assassinated, it was called the National Cultural Center. It was later renamed the Kennedy Center after his death. But before that tragic killing, the federal government was not supporting the National Cultural Center. The Center had to raise its own money. They had national telethons, which Leonard Bernstein conducted. And at one of them, Bernstein said something like, “I’ve heard of a great young cellist, he’s only seven years old, but I want you to hear him.” And you played. I think President Kennedy was there. Do you remember that?

MA: I do, but I remember a slightly different scenario than what you described. I was an immigrant, newly arrived in the United States, and I actually played for Pablo Casals. After Casals left Spain, he moved from southern France to Puerto Rico. I played for him. A couple of weeks later, Casals was asked to play for this new National Cultural Center. He didn’t want to travel from Puerto Rico, and so they inaugurated the telecast and live coverage. He is the one who said I know this kid who plays, and that’s why my sister and I were asked to play.

RUBENSTEIN: Was President Kennedy there?

MA: He was, but what was impressive to me then was the fact that Danny Kaye was conducting the National Symphony Orchestra.

RUBENSTEIN: So, you are seven years old, you are playing in front of the President of the United States, and then you continue to play the cello. But as you got older, did other things intervene? Did you want to play baseball or something else? Did you lose your focus on the cello at all?

MA: One of the reasons I love Pablo Casals is that when he met me, he said, don’t forget to go play baseball.

RUBENSTEIN: Really? Did you play baseball?

MA: No.

RUBENSTEIN: Alright. You went to Julliard, yes?

MA: I did. But let me mention something incredible that you did yesterday. You opened a permanent exhibit at the Kennedy Center. You are the Chairman of the Board at the Kennedy Center, but also the Chairman of the Board at other places too. Why are you the Chairman of so many boards? If you are supposed to be in private equity, doesn’t that take a lot of your time?

RUBENSTEIN: Private equity doesn’t take as much time as you might think.

MA: Is investing no longer interesting to you? You are on the board of Harvard, of the American Academy, of the Smithsonian, of Duke, and of the World Economic Forum.

RUBENSTEIN: Well, you’re on that board too.

MA: Yes, but how do you have time to do all this stuff?

RUBENSTEIN: I don’t play golf, and that saves about ten hours a day. Now back to your life. You are a student at Julliard, which is a great school, but you leave it to go to Harvard. I mean Harvard is not bad either, but why did you decide you wanted to go to Harvard, a four-year college? Many child prodigies go to Julliard or the equivalent.

MA: Well, first of all, I had no idea what college would be like. I had only lived at home, and my family environment was not one in which dialogue could really take place. When you have people telling you who you are, what you think, and how you feel, I didn’t know what I thought or what I felt. But all joking aside, I had an amazing musical foundation from my home. And that allowed me to be incredibly efficient as an undergraduate.

RUBENSTEIN: Were you the class of ’76?

MA: Yes.

RUBENSTEIN: Anybody else famous in that class?

MA: Let me think.

RUBENSTEIN: Wasn’t there a computer guy?

MA: There was a computer guy in Currier House, but he ended up dropping out. And there’s a guy who’s now at the Supreme Court.

RUBENSTEIN: Really?

MA: Roberts.

RUBENSTEIN: Did you know him?

MA: No. I only found out we were in the same class when I had dinner with him.

RUBENSTEIN: So, you graduate from Harvard, and you want to be a professional cello performer. Would you agree that the life of a professional classical music performer is not the easiest in the world?

MA: Well . . .

RUBENSTEIN: You must travel a lot. You are playing every night in a different place.

MA: First of all, when you start out, you’re starving. You take any job.

RUBENSTEIN: Right.

MA: My first summer at camp, some friends asked if I wanted to play a wedding. Fifty bucks, pizza money, it was great.

RUBENSTEIN: Did you ever play at bar mitzvahs?

MA: Of course.

RUBENSTEIN: Early on, about how many hours a day did you practice?

MA: To be honest, I did not practice that much.

RUBENSTEIN: Really?

MA: Yes, but only because I’m very efficient. I told you, I had a great foundation, which meant that I could spend a lot of time doing other things or doing nothing. And that was a great advantage. I was not well schooled, I was not well prepared for college, and I didn’t know how to write papers. After college, I tried to make up for the things missing in my life – from the courses and people that I met to fill in the gaps. So, in a way, my education started after college, with things that I was exposed to through my travels and meeting people at concerts.

RUBENSTEIN: The life of a classical music performer is a life of getting on planes, getting off planes, rushing from place to place, performing, and so forth. How do you deal with jetlag and that hectic pace?

MA: The life of a classical musician, or of any musician, is to find meaning every day. That’s what we all try to do. That’s what you do and is probably the reason why you serve on all those boards.

RUBENSTEIN: But in your case, I imagine that you need to practice. Last night, you played at Wolf Trap. You must have practiced a few hours before your performance.

MA: At least.

RUBENSTEIN: So, when you’re practicing and you make a mistake, do you tell yourself I don’t really have this piece down yet? How many times do you have to practice before you really master it?

MA: Let me ask you the same question. When you go to a board meeting and give a speech, how long have you practiced beforehand? And this book of yours that I’m holding, How to Invest: Masters on the Craft, it is not just a prop. I have actually read the book. And what I’m fascinated with is the fact that as an investor, you characterize yourself and others who invest as people who are incredibly curious, who never stop learning, and who read everything about everything because it all helps. The exact same thing applies to what I do. In music you learn technique, and the reason I practice is so that I can transcend it. What do I mean by that? If I spend 100 percent of my brain real estate concentrating on how I’m going to do something, I’m going to feel nothing. But if I can decrease the amount of brain real estate on the playing aspect of the cello, I can focus on what it’s about. And if I can do that, if I can consistently focus on that – which is something that I’ve seen you do over and over again in your speeches when you get everything right, when you include humor – then that is when the music begins to speak.

RUBENSTEIN: But even when I’m making a speech, I’m sometimes thinking about what am I going to say next? Did you ever make a mistake?

MA: I always make mistakes.

RUBENSTEIN: Do you ever forget the next note when you’re playing?

MA: Yes, but what’s important is what kind of mistake. To quote from your book . . .

RUBENSTEIN: Really? I should have asked you to do a blurb. I will next time.

MA: You say, “Learn how to admit a mistake and to correct it as soon as possible, with the least damage possible. Investors will always make mistakes, but the key for really good investors is learning when to admit them, cut losses, and go on to the next opportunity.”1 When I make a mistake, I just say, oh well, I made a mistake. And you let it go because there’s something more important than that.

RUBENSTEIN: Let’s suppose you’re playing with the National Symphony Orchestra, or some other great orchestra, and they make a mistake, and you know they’ve made a mistake. What do you do? Do you raise your eyebrows?

MA: I’m just going to keep quoting from your book. This is from Ray Dalio. “The company’s culture was key. Having a culture in which there’s thoughtful disagreement and meritocratic decision making, so the best ideas win out, was a big thing. It was a culture in which we would challenge each other’s ideas and hold each other to high standards. High-quality independent thinking, humility, working well with others, and resilience.”2 Working well with others means that it is more important that what you’re trying to do comes through, so when somebody makes a mistake, you push through and make everybody look good. That’s collaboration. Does that answer your question?

RUBENSTEIN: I understand.

MA: Did I get the answer from your book?

RUBENSTEIN: You seem to know the book better than I do. But I wrote it about a year ago. Now back to you. You are unique in the sense that many classical music performers just perform, and there’s nothing wrong with that; they’re really good at it. But you spend a lot of time on cultural issues that are unrelated to classical music. You spend a lot of time going around the country, talking about the importance of learning the arts, the importance of education, and the importance of happiness, among other things. Why do you spend so much time on things that are not related directly to your career as a classical musician?

MA: Because everything is connected. If I can’t figure out how playing a piece by Beethoven connects to your life, to my life, and to the moment that we’re in, then I’m not being a musician. All of you here this evening are incredible at something. You wouldn’t be in this room otherwise. You know the content and you exist in a world that recognizes what you know. So, you’re able to communicate that to other parts of the world. And if you weren’t successful in doing that, again you wouldn’t be in this room. And how you are able to serve the world knowing what you do is the crucial part. For me, that’s the answer of why David, you are so curious. That’s why all of you are members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. It’s all connected. Now let me ask you two questions. Who said the following: “Nature has the greatest imagination, but she guards her secrets jealously.” Did a scientist or an artist say that?

RUBENSTEIN: I would guess an artist.

MA: It was a physicist, Richard Feynman. And who said, “We are nature. If we are disconnected from nature, it’s because we’re disconnected from ourselves.” Was it an artist or a scientist?

RUBENSTEIN: I would guess an artist, perhaps Leonardo?

MA: It was the sculptor Andy Goldsworthy, a wonderful person who works in landscape and nature. Do you believe we are part of nature?

RUBENSTEIN: I hope so, yes.

MA: It’s a good thing that you seem to think that because for the longest time, we didn’t necessarily believe that or act that way. We can learn from nature. If we really are part of nature, wouldn’t we start to make decisions a little differently?

RUBENSTEIN: Let me ask you about classical music. Why do you think the people who often go to classical music concerts have my hair color and seem to be a little older? Is classical music going to fade from our civilization because younger people aren’t interested, or do you think they will eventually become interested in it?

MA: David Oxtoby, president of the Academy, told me that this summer he saw Michael Tilson Thomas conduct the Boston Symphony. And President Oxtoby remembered that Michael conducted the Harvard-Radcliffe Chorus back in 1968. He has been following Michael Tilson Thomas’s career for more than fifty years. Michael is not only a great musician, but with his wonderful partner, Joshua Robison, he has created the New World Symphony in Miami, which trains young musicians who end up going to major orchestras. These young musicians go out and train other young people. The graying hair, yeah, there’s a lot of that. But there are people in this room who are in the music profession, who are training young people, who in turn will train even younger people. We are seeing all this being developed now. I think classical music is quite alive in many places. But we don’t know all of the results yet. You believe in the future. You believe that when you predict the future correctly, you win. Right?

RUBENSTEIN: Yes.

MA: And what we’re betting on is a future that we want to believe in. So, everything that we do – which is the third part of how we get from the content to what is being received right now – impacts our future.

RUBENSTEIN: Unlike some classical music performers, you do what I would characterize as crossover. You work with popular musicians, like James Taylor and others. I can’t imagine Pablo Casals sitting down with James Taylor, but maybe he would have. Why do you work on non-classical music? Is it to broaden your audience? Or because you enjoy it?

MA: The simple answer is, I don’t think in categories.

RUBENSTEIN: So, you see it all as music?

MA: Music is energy. Music is sound. And sound is energy. It moves air molecules, which hit your eardrums, and then your brain interprets what these sounds mean. It has nothing to do with whether it is any particular type of music. It is the reason I went to college: to ask the question, if I hear some sounds, who did it, and why? Does that answer your question?

RUBENSTEIN: It does. Let me ask another question. When you fly on a commercial plane, do you get a seat for your cello?

MA: I do.

RUBENSTEIN: If you could play in any music hall in the world with the best acoustics, which hall would it be?

MA: Every hall – and by the way, Klarman Hall is a beautiful hall and music would sound fantastic here – is like an instrument. It is not static; it has characteristics. Is there a best horse in the world? A best car in the world? A best house in the world? You learn to accommodate what a house is, what a car does, what a horse is. And it’s the same thing with a hall. Symphony Hall is gorgeous. It’s rectangular, and it has certain characteristics, which if you play jazz in it, it is going to sound too swimmy. But it sounds great when you play Brahms. So, you need to find the best hall for certain types of music.

RUBENSTEIN: So, Carnegie Hall is no better than Symphony Hall?

MA: Is there a best parent in the world? Why do we have to have the best of something? Why can’t we just say that these are the characteristics of something, and if you’re going to do X activity in it, you need to know that. Now I don’t know anything about basketball, but my friend Lynn Chang tells me that Larry Bird used to spend hours in the old Boston Garden, throwing a basketball so that he could learn every little nook and cranny on the floor and use that information. It was his version of curiosity: to know the floor that he would be playing on so that no matter the angle of the ball, he would know what the reaction was going to be. That same thing applies to music halls. If I’m playing in a hall that I don’t know, I spend an extra fifteen minutes in the space. If I’m playing a recital with piano, well a piano and cello have a very different acoustic projection. With the piano lid open, the sound projects in a very wide way. For the cello, the way you point the F-holes, which are the holes in the front of the cello, determine where the sound goes. So, what are my choices? In this hall, there’s an overhang over there, so there shouldn’t be any problem with the sound. There are a lot of music theaters that are converted movie theaters from the 1930s, and they have a long overhang. So, what happens? The sound doesn’t get a chance to bounce into that part of the hall. In those cases, I would point my cello, the F-holes, toward that specific part, because the people beneath it will naturally hear less. In this hall, I need to get more projection so by moving my chair six inches back, I can use the back wall. This is the type of fiddling that is normal.

RUBENSTEIN: Do you think this is a good hall for you to play the cello? Are the acoustics good here?

MA: I think the acoustics would be fine.

RUBENSTEIN: Let me ask you about a piece you played yesterday. You and I were at the Kennedy Center for its 50th anniversary celebration. Let me acknowledge Deborah Rutter, president of the Kennedy Center, who is in the audience with us tonight. One of President Kennedy’s granddaughters was there for the celebration. In your remarks, you talked about President Kennedy and how Pablo Casals did not want to play in certain countries that were supporting Franco. But he made an exception for the United States because we had done other good things. So, Casals played at the White House. And then you played the very piece that he had played in the 1960s. Could you play that for us? And my other question is, suppose you have somebody who’s 73 years old, and he wants to learn the cello. Do you think it’s possible at that age to become a cello player?

MA: Let me ask you a question. If there’s an Asian musician who’s 66 years old, past retirement age, and he reads your book, could he learn how to invest?

RUBENSTEIN: I would encourage that person to hire some good money managers. The reality is I’m not going to be a great cellist and you’re not going to be a great private equity investor.

MA: This is the difference between us. I know I’m not going to be a good private equity person. But a person as intelligent as you, why wouldn’t you want to be a cellist?

RUBENSTEIN: Well because I would want to be Yo-Yo Ma. You have a great life, and people sometimes recognize you. You are world famous, while private equity people are a dime a dozen compared to great cellists.

MA: But the only private plane I own is a five-inch model that I keep in my home. The difference between investing and playing an instrument is this: when you play an instrument, it doesn’t matter who thinks you played well. If you use your head, your heart, and your hands together, and you get pleasure from that, then that is the meaning. Now, if I started investing with that same intention, the results would be disastrous.

Let me quote again from your book. This is from your interview with Seth Klarman, who is in the audience with us today. He is answering your question about whether he has any interest in writing an updated version of his book. And Seth says, “I would write about the criticality of team. Who’s on your team? How do you motivate them? Culture is critical for every organization.”3 It’s interesting that you spend a lot of time building your team so that the culture is just right. There’s another place in the book in which Larry Fink says, “Culture is what binds an organization. Culture is what makes an organization differentiated and unique. I spend at least 30 percent of my time focused on culture if not more.”4

And there’s more. Ray Dalio says that out of three things that are important, “Third, the company’s culture was key. Having a culture in which there’s thoughtful disagreement and meritocratic decision-making, so the best ideas win out, was a big thing.”5

RUBENSTEIN: My next book is going to be on how to play a musical instrument, and I’ll have you in that one.

MA: You give ten principles that are important for young investors. Let me point out a few of them. One is, “Follow up on commitments and promises.” In other words, honor your word. Another one is, “Focus on developing a reputation for humility, cooperation, and ethical behavior. . . . A reputation for being willing to listen to others, accept advice, not brag, and help others will go a long way toward building a successful and admirable career. And do not be tempted to cross ethical lines.” Another is, “Learn how to admit a mistake and to correct it as soon as possible.” And the last principle is, “Find areas outside of investing that can enable you to broaden your scope as a human, and experience things other than the pursuit of money and professional success. Working around the clock just on investing is honestly not a prescription for success on a long-term basis in the investing world.”6

RUBENSTEIN: So, are you saying that playing classical music all the time is not going to make you happy?

MA: We are basically talking about the same thing. Building a culture, rebuilding our democracy or renewing it: that is where one-third of our effort should be. That is what I do in music. After I learn the content and after I learn to play in tune, the last third is how is it received? Is what I’m doing being absorbed or living in somebody else? Because if it isn’t, then whatever I do is dead on arrival.

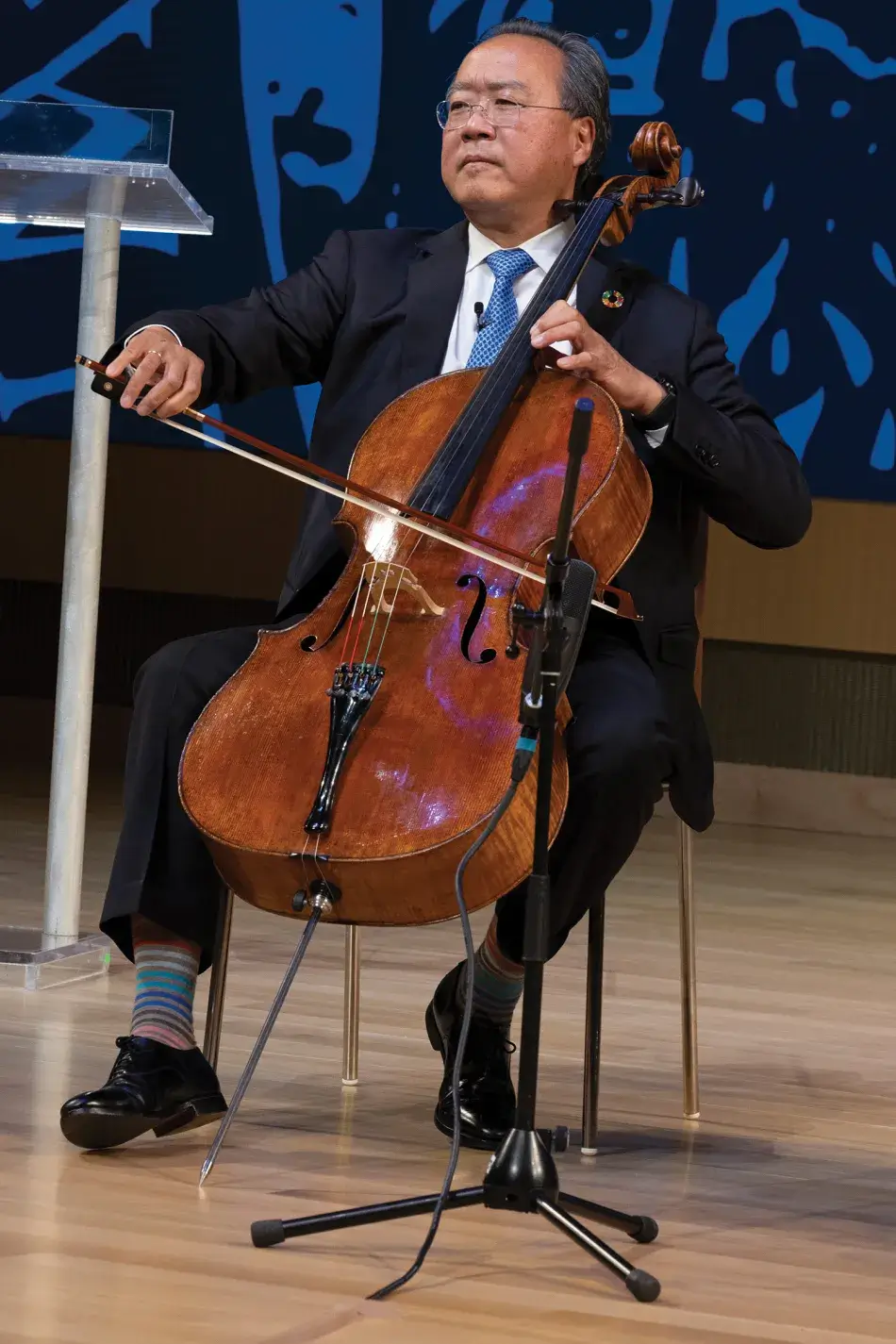

RUBENSTEIN: Speaking of democracy, how about Pablo Casals’s piece? Are you ready?

MA: Another value is persistence. One reason I love Casals, even as a nine-year-old, was because he used to say: I’m a human being first, a musician second, and a cellist third. And to my nine-year-old ears, that sounded really good. But to my sixty-six-year-old ears, I really believe it. About three years ago, before the pandemic, I went to visit his house outside of Barcelona, which is now a museum, and one of the things I saw was the very careful accounts that he kept of the several fortunes he gave away to refugees who were in need both during the Spanish Civil War as well as during World War II. And the accounts are reams. And I also saw the letters that he wrote after the war to newspapers, to politicians, to diplomats about what the Allies promised they were going to do to get rid of fascist governments, and they didn’t. In protest, he gave up playing. And it was out of admiration for President Kennedy that he broke his vow to stop playing. That White House concert was a signature part of the Kennedy administration, so much so that we remember that concert sixty-one years later. I think everything that we do at one level is connected with how we create memory, how we pass on things that are valuable to another generation. How we define that is the essence of all of our work.

At the end of the concert, Casals said, “I am going to play for you the piece that means the most to me. It is a folk song from my native Catalonia, and it is called ‘The Song of the Birds.’ Every Catalonian knows this song because it means freedom.” Everything that we do at the American Academy right now is about how we are going to make sure that the democracy that we believe in can thrive and continue to thrive in ways that benefit our entire population. Birds are migrating right now. They are crossing borders; they are crossing silos. So, whether it’s the arts or the sciences, I know the Academy is attempting to cross borders.

[At the end of the conversation, Yo-Yo Ma performed Pablo Casals’s “The Song of the Birds.”]

© 2023 by David M. Rubenstein and Yo-Yo Ma

To view or listen to the presentation, visit www.amacad.org/events/2022-Induction-September.