On October 11, 2014, as part of the Academy’s 2014 Induction weekend program, new Members were briefed on the Academy’s research projects and studies. The speakers, who play an active role in one or more Academy projects, highlighted the studies’ current activities and the many opportunities for new Members to participate. The presentations focused on projects in Science, Engineering, and Technology; Global Security and International Affairs; and the Humanities, Arts, and Education. Below is an edited version of the speakers’ remarks.

Science, Engineering & Technology

New Models for U.S. Science & Technology Policy

Neal Lane

Neal Lane, a Fellow of the American Academy since 1995, is the Malcolm Gillis University Professor and Professor of Physics and Astronomy Emeritus at Rice University and a Senior Fellow for Science and Technology Policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. He chairs the Academy’s Initiative on Science, Engineering, and Technology, and is Cochair of the New Models for U.S. Science and Technology Policy study.

Throughout its history, the American Academy has been deeply concerned with both the pursuit of scientific knowledge and the implications of scientific and technological advancements for society. Those concerns lie at the heart of the Academy’s projects in the area of science, engineering, and technology, which our first panel of speakers will discuss.

In 2008, the Academy published its first ARISE (Advancing Research in Science and Engineering) report. This study, which was chaired by Nobel laureate and chemist Thomas Cech, focused on two primary issues: support for early-career investigators and support for high-risk/high-reward research. Last year, the Academy published a follow-up report, appropriately called ARISE II, which explored how to encourage transdisciplinary collaborations and create structures to allow those collaborations to flourish. The ARISE II project was chaired by Keith Yamamoto of the University of California, San Francisco and Venkatesh “Venky” Narayanamurti of Harvard.

In September 2014, the Academy published a new report focused on the future of the national science and engineering research enterprise entitled Restoring the Foundation: The Vital Role of Research in Preserving the American Dream. I had the privilege of cochairing that report with Norman Augustine, retired CEO of Lockheed Martin. Our report is dedicated to the late Chuck Vest, who often remarked about the path that took him from a kid growing up in West Virginia to the President of MIT: how important education and science and engineering were to him and to his life, and how he lived the American Dream. While the focus of our report is on the importance of basic research, we frame our arguments around the American Dream of a quality livelihood in a strong economy, which, among other things, requires quality education and a robust research enterprise.

The suggestion that the Academy carry out the study came from a Fellow of the Academy, a past university president concerned about shortcomings in science policy. A little over a year ago, the American Academy assembled the New Models for U.S. Science and Technology Policy Study Committee, which comprised leaders from various sectors, many of whom have experience in the world of policy. They set out to explore what the nation should do to ensure America’s leadership in science, engineering, and technology in an increasingly complicated world. The Academy staff – in particular, John Randell and Hellman Fellow Dorothy Koveal – also provided strong support for the project.

Throughout the year, the project chairs, Committee members, and Academy staff met with administration officials, members of Congress on both sides of the aisle, academic and business leaders, leaders of the research community, and others who care about the future of science, engineering and technology in our country. These meetings informed the Committee’s research and the resulting report, which was released on September 16, 2014. The report rollout included a Congressional briefing in Washington and a roundtable and dinner attended by representatives of several nongovernment organizations that share the Committee’s concerns.

Now Nancy Andrews will speak about the basis for the study, how it was framed, and why.

New Models for U.S. Science & Technology Policy

Nancy C. Andrews

Nancy C. Andrews, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2007, is Dean of the Duke University School of Medicine and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs. She is also the Nanaline H. Duke Professor of Pediatrics and Professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology. She previously served as Director of the Harvard-MIT M.D.-Ph.D. program and as Dean of Basic Sciences and Graduate Studies at the Harvard Medical School. She is a Member of the Academy’s Board of Directors and is a committee member for the New Models for U.S. Science and Technology Policy Study.

Restoring the Foundation asserts that the American science, engineering, and technology research enterprise is at a critical inflection point, and that the decisions policy-makers and leaders make over the next few years will determine the trajectory of American innovation for decades to come. The report describes the challenges that lie before us and is meant to serve as a call to action. In the words of Norman Augustine, who cochaired the Committee, “We must start to think about our future if we are to have a future.”

Looking back, America’s remarkable post–World War II rise to international preeminence in science and technology can be attributed to decades of investments made in research and education. We see the benefit in our own lives: our life expectancy is nearly twice that of our grandparents because many devastating infectious diseases have been conquered and many other conditions, such as cancer and coronary artery disease, are much less likely to be lethal. We carry pocket devices that not only let us communicate (and take selfies) from almost any place on the planet, but also can instantly provide more information than a library.

The past seventy years of research and innovation have also provided enormous economic benefit in the form of new efficiencies, businesses, and careers. But America’s future does not look as bright. In a number of areas, we can no longer claim the preeminence that we have taken for granted. As a country, we are seventh in the world in basic-research investment and tenth in total research-and-development investment; our students are seventeenth in reading, twentieth in science, and twenty-seventh in math.

As our investment in research has languished, other countries have recognized how vital a strong research enterprise is for economic growth and for the quality of life of their citizens. They are now trying to emulate America’s successes. In less than ten years, China is projected to outspend the United States in research and development (R&D), both in absolute terms and relative to the economy. We risk losing the advantage America has long held as an engine of innovation that not only generates new knowledge and products, but new jobs and industries.

Innovation relies on breakthrough discoveries, which are largely the products of fundamental, curiosity-driven, basic research. We therefore believe that basic research is the foundation upon which the nation’s science, engineering, and technology enterprise rests. Most basic research takes place in universities, but the primary source of funding for this research is the federal government, not the universities themselves. The government-university partnership dates back to World War II. The U.S.’s basic research enterprise was bolstered in the mid-twentieth century when a number of large corporations also established in-house R&D laboratories, such as the iconic Bell Labs, which supported a considerable amount of basic research. An impressive number of Nobel prizes were awarded to researchers from those industry labs. But Bell Labs and many of the others have closed. Companies increasingly depend entirely on the government and universities to provide the basic-research pipeline for innovation. They find it increasingly difficult to justify the long-term – and often risky – investments required for basic research, even as the demand for new breakthrough discoveries persists.

America needs a more robust partnership between government, universities, industry, and philanthropy. Other countries have used this strategy. For example, Germany’s Fraunhofer Institutes, Taiwan’s ITRI, and Singapore’s A*STAR have all launched initiatives that encourage the fluid transfer of ideas, innovations, and people across sectors. Our committee recognizes that we have made recommendations for increased support at a time when America has a large and growing budget deficit. However, as we emphasize in the report, we believe that research is an essential investment: there is a deficit between what America is investing and what it must invest to remain competitive in innovation, scientific and health-care advances, and job creation.

Adding to the challenge is the fact that our government does not have good mechanisms to plan for reliable research funding over the long term or to provide capital for research infrastructure, new buildings and centers, and advanced research technologies. Additionally, the productivity of America’s researchers has been crippled by policies that result in unnecessarily burdensome administrative tasks and piles of paperwork that take researchers’ time away from their research. Recently, political interference in funding decisions has become a larger problem. There are also workforce challenges. Furthermore, a boom-and-bust pattern of NIH appropriations has produced a research enterprise larger than what the federal government will support. This has left many bright young scientists questioning their futures and many universities trying to rebalance their research portfolios. In short, we must not only invest, but also generate a framework in which this investment can thrive. The future of the nation’s research enterprise depends on it.

Neal F. Lane:

I think it is fair to ask, “Why another report?” Many related studies on this issue have been conducted by reputable organizations, and many important reports have offered informed policy recommendations. But we felt strongly that the American Academy could add value to the conversation, specifically by focusing on the unique importance of research – basic research in particular – in all fields of science and engineering. I want to emphasize again Nancy’s point that discoveries coming out of basic research – the search for fundamental knowledge – provide the foundation for applications to meet national needs. Investing in basic research offers high social and economic returns. Federally funded research at American universities, for example, supports the health of institutions that produce new knowledge and well-trained graduates that are clearly vital to the future of the country. And while U.S. industry makes it clear that companies depend on access to new knowledge and fresh talent to stay competitive in world markets, its investment in basic research – where specific product applications and sales cannot be foreseen – is often lacking. That is why the federal government must bear the principal responsibility for the support of basic research.

Restoring the Foundation includes three overarching recommendations and several policy actions that would support them. The first prescription argues for sustainable research funding with long-term goals. This is about money – what the federal government invests and how it makes investment decisions. As Nancy mentioned, while the U.S. commitment to basic research has vacillated since the early 1990s, other nations have learned from our past successes and are forging ahead. Our history shows, however, that sustainable funding is not impossible. For nearly twenty years, between 1975 and 1992, the federal investment in basic research followed a remarkably steady path, growing in real terms at over 4 percent a year, despite serious economic and political turmoil (for example, the 1973 oil embargo, the great inflation of 1979–1982, and the final years of the Cold War). Those investments are paying off right now in terms of the products, services, jobs, and economic gains that basic research has made possible. We argue that the United States needs to recommit to the importance of basic research and get funding back on track. We recommend specific short-range and long-range targets, which are made explicit in the report.

We also recommend several changes in the federal budget process. We highlight the value of multi-year appropriations. And while we realize that there are Constitutional limits on what Congress can do, change is still possible within the current state of law. For example, a rolling five-to-ten-year plan for the federal funding of research and development could be released with the president’s annual budget request to Congress. In addition, a capital federal budget could be created for research infrastructure, which is common practice for corporations but something our government simply does not do.

Our second prescription is to ensure that the American people receive maximum benefit from the research they pay for. To this end, we recommend several actions that can be taken by the funding agencies, the White House, the Office of Management and Budget, and universities to reduce wasted time and effort by researchers. Increasing efficiency would allow researchers to be more productive in their research and reduce unnecessary cost burdens on the universities themselves. Funding agencies also need to continue their efforts to address the plight of early-career researchers and to give proper weight to truly transformational ideas. But we emphasize that funding decisions of individual grants should continue to be based on expert merit-based peer review and managed by the funding agencies.

Our third prescription points to the need for a new and robust partnership between government, universities, and industry, which we might call Vannevar Bush II in reference to the man who designed the government-university partnership that was put in place at the close of World War II. Nearly seventy years after Vannevar Bush wrote his legendary Science, the Endless Frontier, the world is a very different place and the country needs a very different kind of partnership, one that may require some years to put together. In our report, we recommend policy reforms that would lower existing barriers preventing close cooperation between universities, national labs, and the companies that depend on them for new ideas, new technologies, and a highly educated and skilled workforce. For example, several universities are changing their approach to intellectual property in order to facilitate the translation of research discoveries to industrial applications, reduce university costs, and improve synergy with industry. We applaud those efforts and encourage other universities to reconsider their policies and change them where appropriate.

This is an abbreviated summary of our report. We would like to leave you with two key points. First is the argument for sustainable federal funding with special attention to long-term considerations; and second – perhaps even more important – is the imperative to ensure that those investments benefit the people who pay for them. The Academy, under President Jonathan Fanton’s leadership, is strongly supportive of the report, and we will all participate in every way we can to make sure these recommendations see actions.

The Alternative Energy Future

Barbara Kates-Garnick

Barbara Kates-Garnick is the former Massachusetts Undersecretary of Energy. She is currently Professor of Practice and Director of the Energy, Climate, and Innovation program at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. She is a member of the Advisory Committee of the Academy’s Alternative Energy Future project.

First, I would like to acknowledge Maxine Savitz and Robert Fri, who cochair this project.* They are playing a critical role in helping us understand the transformation of our physical energy infrastructure and our opportunities for an alternative energy future.

The earth is warming. Its surface temperature has risen by 1.4 degrees centigrade over the past century and is projected to rise further: between 2 and 11 degrees centigrade over the next hundred years. A global temperature rise of 2 degrees centigrade has been considered the upper limit for a “safe” temperature rise: anything higher and we risk seeing the dangerous impacts of climate change. Recently even that threshold has been deemed too high.

Our energy numbers, however, do not reflect the gravity of the climate change reality. In 2012, U.S. electricity production came mainly from fossil fuels and generated over 32 percent of our greenhouse-gas emissions. The transportation sector contributed 28 percent to emissions that year, mainly from gasoline and diesel. Given that these two sectors together make up over half of our emissions, they need to become the focus of change in terms of alternative technologies, economics, and behavior if we are to slow down global warming within a reasonable timeframe.

An alternative-energy project, at this point, should be focused on innovations to our physical energy system, and the behavioral and policy designs that are needed to adapt to a transforming energy infrastructure. It seems very difficult for us to change systems, regulatory paradigms, and behavior to deal with a problem that affects vested interests, is global in its impact, and is likely to intensify over time. All of these factors have made the development of an international climate regime extremely complex – hence the need for this Alternative Energy Future project.

We must change how energy is produced, delivered, and consumed. Energy is delivered instantly to our homes and businesses through a massive infrastructure that was built on technological innovation and continues to evolve. Now, however, we must find new technological innovations. Renewable energy is gaining market share and achieving parity with fossil fuels, but integrating an intermittent resource (such as renewables) into the power grid is complex, and we must determine how to maximize the value of such resources while reducing our use of fossil fuels.

We can also educate consumers about energy efficiency practice, which is equivalent to any other resource. These efforts will limit the growth of power plants. But customers also need to see real-time price signals that will change their behavior in a meaningful way. We are also entering the world of distributed generation, where solar energy and other technologies permit consumers to produce energy on site and even to separate themselves from the grid entirely through smaller energy systems called microgrids.

All of these are complex technologies, and integrating them is absolutely necessary to making progress toward a sustainable energy future. At the same time, there remains a very essential role for social science, because we must contend with the economic and social challenges of transitioning technology. We can anticipate and plan for disruptive change, but participants in our project also point out the need for smooth transitions and changes that are adaptable and durable. These are very important concepts: in the highly transparent and communicative world in which we live today, failure is not an option. Think of the times when your power goes out: you cannot get to your computer, so you cannot do your work. The American workforce depends more than ever on being connected to the energy grid, so reliability must be a critical aspect of any development we make.

So, rather than developing a framework in an analytical silo, focusing only on one facet of a new technology, we must integrate the disciplines. Whether we are instituting a cap-and-trade policy or a carbon tax, we must consider the governance structures and institutions that must be developed to oversee these economic mechanisms. Alternative-energy investments cannot be made in a climate of economic uncertainty.

We must think about markets: Who are the winners and losers at the end of any given policy decision? What is the risk profile? And what is the impact of volatility and change? Reconciling differences among stakeholders will require that they recognize common values of equity and economic growth. Furthermore, we must grapple with the challenging question of how these values may conflict with one another as we build durable economic and legislative systems to deal with climate change. We must show that entrepreneurship and innovation have a better chance to flourish in a society that has a basic commitment to solving climate change. In these ways, the role for social science is quite evident: it will help us define the playing field, deal with disruptive events, and encourage collective action through integration rather than dislocation.

Whatever the path forward will look like, it will require the analytical capabilities of social science to ensure that transformative change can be adaptive enough to cope with future unknowns and durable enough to build a system that survives into future generations.

* The Academy mourns the passing of Robert Fri (November 16, 1935 – October 10, 2014).

Public Understanding of Science & Medicine: Public Trust in Vaccines

Seth Mnookin

Seth Mnookin is the author of The Panic Virus: The True Story behind the Vaccine-Autism Controversy, among other books. He is the Associate Director of the Graduate Program in Science Writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Cochair of the American Academy’s Public Trust in Vaccines project.

Today I will very briefly discuss the history of scientific advances in medicine and the social reaction to those advances in the past one hundred and fifty years. Then I will tell you about the Public Trust in Vaccines project, which I cochaired with Barry Bloom and Edgar Marcuse.

Vaccines, along with antibiotics and clean drinking water, are one of the three advances in medicine and public health that most dramatically changed the way we live in the world. If you look at the average American lifespan over the past century, you can see a remarkable jump of several decades. That is not due to people living longer per se, but rather to people not dying at very young ages of preventable conditions. We went from an average longevity of about fifty years to about seventy. This is not because all of a sudden fifty-year-olds were living for twenty more years, but because far fewer children were dying. One of the main reasons for that is the development and use of vaccines.

The effect of vaccines has been felt most strongly in industrialized and Western nations; among those, the effect has been strongest of all in the United States because of our mandatory school-age vaccination laws, which do not exist in the U.K. and much of Western Europe. But the effects of vaccines actually extend far beyond public health. For example, if you look at the prevalence of vaccines over time juxtaposed with other social trends, you can see a stark correlation between women in the workplace and the number of vaccines that had been introduced. When mothers no longer had to spend weeks or months of every year quarantined with their children, many more women were able to go to work.

Fast-forward to the end of the twentieth century: Over the past fifteen years, there has been a series of vaccine-related scares – in the United States, the U.K., and to some extent in Western Europe – that have largely originated from assorted frauds and charlatans, but have gained real traction because of parent-activist groups. These groups are, for the most part, very well-meaning, although they are mistaken in their fears. In retrospect, the public-health apparatus was completely unprepared to deal with these scares. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, we were still primarily operating in a paradigm in which doctors gave authoritative recommendations and patients followed them. But patients were no longer relying solely on medical authorities for information about their health, and to some extent, these vaccine-related panics were related to the way public health authorities communicated to the public. When, for instance¸ the United States decided to recommend removing a mercury-based preservative from vaccines in the late 1990s, the CDC released a statement saying that the decision was made despite there being “no evidence of harm.” Many parents interpreted this statement to mean that there was about to be evidence. The American Academy of Pediatrics said, “We’re going to make safe vaccines even safer.” Well, if parents are told something is safe, they do not assume that it will be on a sliding scale.

Over the past decade, we have seen overall vaccine-uptake rates in this country remain fairly high. But at the same time, we have seen concentrated pockets of under-vaccination around the country. Especially in the past five or six years, we have started to see some significant effects of under-vaccination, most notably in a series of measles outbreaks. The past several years have seen the largest number of measles outbreaks since the mid-1990s. This is especially remarkable because the World Health Organization declared in the year 2000 that measles had been eliminated from the United States. We are now seeing a resurgence of a disease that was completely eliminated. That is so crucial partly because, according to a study about a 2008 measles outbreak, containing and treating each individual case cost public health providers more than $10,000. When the number of cases climbs to a couple of hundred or a couple of thousand, the costs become very high.

The American Academy became interested in this very salient issue and convened a committee to examine it. The three cochairs of the project – Barry Bloom, Edward Marcuse, and I – felt that instead of discussing our intuition about which strategies would best address vaccine hesitancy, we needed evidence-based research that provided clear answers.

Our committee, which included individuals from the CDC and the National Vaccine Program office, gathered together in 2013 at the Academy. The result was the Public Trust in Vaccines report, which defines a research agenda. We found three areas that we thought especially needed attention: parental attitudes and knowledge; the events of the medical encounter; and specific issues regarding at-risk communities. Responses to this report have been extremely positive; we received attention from Science magazine and a request from the CDC for a briefing. We have drawn attention to an urgent need for more research into the science of science communication. Trust in science and scientists is dropping; depending on how you measure it, it may actually be at an all-time low. As we have heard already in this panel, the way we interact with science will have very dramatic effects on the future of our society. I appreciate the Academy’s support for the project, which I believe sends a hopeful signal that faith in the usefulness of this type of research remains.

Global Security & International Affairs

Committee on International Security Studies

Steven E. Miller

Steven E. Miller is the Director of the International Security Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School. A Fellow of the Academy since 2006, he is the Cochair of the Academy’s Committee on International Security Studies and Codirector of the Academy’s Global Nuclear Future Initiative. He also serves as a member of the Academy’s Council.

First, let me begin by congratulating the new inductees. I can personally attest that if you embrace the opportunity that the Academy represents to advance your personal and professional agenda, then the honor being bestowed on you today has the potential to alter the trajectory of your work and be a truly life-changing event.

We thought it might be interesting to begin by providing you with a snapshot of the origins and evolution of the Committee on International Security Studies. In 1958, the Committee on Arms Control was founded here at the Academy. Its intellectual history can be traced to a public appeal made by Albert Einstein and Bertrand Russell in 1955 that called attention to the dangers of nuclear weapons and warned of the “species-threatening nature of nuclear technology.” It has become known as the Russell-Einstein Manifesto and was Einstein’s last public act.

This notion was picked up by a Canadian-American industrialist named Cyrus Eaton, who had made his fortune in railroads. He funded the first meeting of Soviet and Western scientists in 1958 in his home village of Pugwash, Nova Scotia. The meeting was intended to try to bridge the chasm that existed between the Soviet and the Western world. Partially thanks to this meeting, the intellectual construct began to emerge that even enemies share a common interest in avoiding mutually annihilating nuclear catastrophe; that managed competition, however intense, would be preferable to unconstrained rivalry. This led to a fundamental question: how can we collaborate with our bitterest enemy in order to minimize the nuclear instabilities and dangers that menace us both? Up to that point, any reference to disarmament had been largely rhetorical, coming in the form of grand pronouncements proclaiming “our great fidelity to general and complete disarmament.” But after the Russell-Einstein appeal gave rise to a more sober interest in de-escalation, the challenge was to craft a meaningful policy approach to pursue these goals, and so the American Academy’s Committee on Arms Control was formed. Among the participants were Academy Fellows Henry Kissinger, Thomas Schelling, and Paul Doty. Out of the Committee’s work emerged two issues of Dædalus that were later republished as an edited volume under the title Arms Control, Disarmament, and National Security, which became the so-called bible of arms control. It also led directly to the production of a small book by Thomas Schelling and his then – graduate student Morton Halperin called Strategy and Arms Control, which is also a classic in the disarmament literature.

Since that first committee was formed, the Academy has always had a standing body, under various names, devoted to addressing arms control and international security. In the 1980s, it was heavily involved in the debate over missile defense spawned by President Reagan’s Star Wars initiative. In the 1990s, the Academy played a significant role in addressing questions of sovereignty and intervention, which were catalyzed by the Balkan crisis and by the emergence of the notion of responsibility to protect (which suggested that the international community had not only a right but an obligation to intervene on behalf of threatened peoples). More recently, the Academy has spearheaded a series of significant projects on corruption and international security. Professor Robert Legvold of Columbia University led a project on ordering the post-Soviet space, which looks particularly prescient now. John Steinbrenner of the University of Maryland has recently completed a project under the auspices of the Academy examining the question of governance of the human exploration of outer space. We are pleased that the Academy continues to maintain its historical role as a leading voice on international arms control and security.

New Dilemmas in Ethics, Technology & War

Scott D. Sagan

Scott D. Sagan, a Fellow of the Academy since 2008, is the Caroline S.G. Munro Professor of Political Science at Stanford University and a Senior Fellow and former Codirector of Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation. For the past six years, he has also been the Codirector of the Academy’s Global Nuclear Future Initiative.

This panel will be discussing two projects: Ethics, Technology, and War and the Global Nuclear Future. I will begin by discussing the intersection between them. Just after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, Fortune magazine published the results of a poll that asked Americans their opinions about the attacks. More than 53 percent of the public expressed approval for the bombing and 13 percent wished that there had been a demonstration strike on an unpopulated area first. What was most surprising was that 22.7 percent said that the U.S. government should have dropped many more bombs before giving Japan a chance to surrender. I used to think that this support for what could be called “atomic retribution” had to be understood in the context of Pearl Harbor, the massacre at Nanking, and the Bataan Death March, all of which were fresh in the public consciousness. However, recent research has suggested that something more disturbing was displayed in this 1945 poll.

In 2013, my colleagues Benjamin Valentino, Daryl Press, and I published the results of a survey experiment in which we asked a representative sample of the American public to read a hypothetical story in which Al-Qaeda was suspected to be building a primitive nuclear device in a cave in a neutral country. After reading the story, the public was asked whether they would approve of the United States using nuclear weapons to attack that site, given a certain probability that such a nuclear strike would effectively destroy the target. With different groups of subjects, we then varied the effectiveness of a nuclear strike versus a conventional strike against the Al-Qaeda cave. What surprised us was that 18.9 percent of the public preferred using nuclear weapons, even when it was clear they were not needed, because a conventional strike was posited to have the same 90-percent probability of destroying the Al-Qaeda cave. When, with other groups of respondents, we increased the efficacy of the nuclear strike to 90 percent and reduced that of the conventional strike to 70 or 45 percent, numbers of individuals preferring or supporting nuclear strikes rose dramatically. Although further research on this topic would be most helpful, our results suggest that a significant portion of the U.S. public views the potential use of nuclear weapons against an enemy in a very positive light, and that there is much less of a taboo around using nuclear weapons today than was previously assumed.

This raises important questions about the degree to which key principles of just-war doctrine, such as noncombatant immunity and proportionality, have been integrated into American public opinion. As you have heard, the Academy has had a long and distinguished tradition of dealing with nuclear issues and arms control. It has a slightly less lengthy but no less distinguished tradition of addressing ethical issues. In 2000, the American Academy published The United States and the International Criminal Court, a volume edited by Carl Kaysen (distinguished economist, former government official, and longstanding Cochair of the Committee on International Security Studies) and Sarah Sewall (then at the Harvard Kennedy School, and now the Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights). And, in 2003, an entire issue of Dædalus was published in which philosophers, political scientists, lawyers, and economists addressed challenges with global justice.

A new Academy project is gathering together a diverse group of individuals – including scholars, soldiers, and diplomats – interested in different aspects of just-war theory and application, and the challenges that modern technology creates. We put together the New Dilemmas in Ethics, Technology, and War project to analyze questions about ethics and justice before, during, and after modern wars. We are also asking ethical questions about which technologies are helpful and which create major challenges, whether it is weaponry (such as drones and biological weaponry), technologies for providing early-warning capabilities (such as satellites and expanded cell-phone usage), or medical technology improvements (which may reduce the mortality rate of soldiers or civilians in war, but could create new issues concerning higher numbers of wounded people after conflicts). Advanced weapons systems, for example, have led to optimism about the possibility of reducing collateral damage in war, but they have concurrently raised concerns about whether states now find it too easy to use force. This is a very new project, and we do not yet have the answers to these questions. But I do believe we are asking the right questions.

New Dilemmas in Ethics, Technology & War

Janne E. Nolan

Janne E. Nolan is a faculty member at the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University, where she chairs the Nuclear Security Working Group. She is also a long-serving member of the Academy’s Committee on International Security Studies.

Issues of ethics in national security and in war in the twenty-first century go straight to the heart of the question of the strategic imperatives of American engagement. The question of the legitimacy of American operations is not a side note or a non-essential matter, as has been suggested by some academics and practitioners. Public perception of the legitimacy of our engagement and methods is actually an absolutely essential and critical ingredient in their success and effectiveness.

My contribution to this larger project relates to the paradoxical but systemic tendency in the United States to underestimate – and often misconstrue – the nature and costs of the wars and engagements into which we enter. There is also a persistent pattern in U.S. military engagements of operating with a flawed conception of the conditions on the ground and then trying too late to adjust to the miscalculations. Where does that come from? We are working with individuals doing case studies of situations in which such discrepancies existed between a caricatured prediction of the engagement and its reality. This falls directly into larger questions about just war. What do we do when our civilian leadership is wrong and misinformed or marginalizes available information? Indeed, in many of the case studies that we have explored so far, we have found a common tendency to marginalize not only complex information, but also information that is discordant with the core assumptions that are driving a push to intervene. This constitutes an interruption in the flow of information and an interruption in the marketplace of ideas that often produces catastrophic and dire consequences. These are first borne by the military and then, subsequently, by entire societies.

The interdisciplinary study that Scott Sagan conducted and described so well is precisely the type of analysis we should be doing. This analysis, however, often results in a conversation that unfortunately rarely happens in Washington, where there are dramatic divisions between discussions of strategy, humanitarian intervention, and ethics. It is very infrequent that all of these threads are brought together, but it is our goal to do so, and in the process explore sensitive but vital questions. One is civilian accountability and leadership accountability: we have a greater understanding about military command authority and responsibility, but we have comparatively very little on the side of civilian leadership. The second under-addressed factor we will explore is education: it is fundamental to teach people to be more critical thinkers, particularly in the area of national and international security. After the 2003 invasion of Iraq, many studies concluded that particularly intelligent people had a failure of imagination and failed to speak truth to power about the invasion. What the studies may have overlooked is the fact that the consequence of speaking truth to power is often professional ruination. We want to address this issue as well, and encourage unbiased research that cuts across disciplines to contribute to a healthier policy debate about war.

The Global Nuclear Future

Robert Rosner

Robert Rosner, a Fellow of the Academy since 2001, is the William E. Wrather Distinguished Service Professor in the Departments of Astronomy and Astrophysics and Physics at the University of Chicago. He is a former head of the Argonne National Laboratory. He is also the founding Codirector of the Energy Policy Institute at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago. He is a member of the Academy’s Council and serves as Codirector of the Academy’s Global Nuclear Future Initiative.

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and its aftermath have given the United States a new perspective on the global nuclear future. Certain other countries have also clearly taken note of the significance of the disaster, the most prominent example probably being Germany. But the majority of the world has seemed relatively unperturbed by this event. In fact, there is considerable evidence that a growing number of countries have a burgeoning interest in nuclear power. Consider, for example, the United Arab Emirates; in particular, Abu Dhabi. One might think that it would have enough fossil fuel to last a good while for energy production and desalination. But, in fact, four nuclear plants are being built there.

We have focused on the issue of how to cope with this expansion – and encourage safe, secure, and sustainable management of nuclear power – when much of it is happening in nations that may be unprepared, both technologically and in their human infrastructure, to deal with its consequences. Our focus has primarily been on the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Specifically, we have engaged with the so-called nuclear newcomers – Vietnam, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Jordan, and Malaysia – and, also important, legacy countries such as Japan and Korea. Why Japan and South Korea? Both countries have a classic problem of legacy countries: namely, storing nuclear waste. Bringing legacy countries (which are better-poised and highly incentivized to deal with nuclear waste) to the same table as the nuclear newcomers is important to the success of our ongoing projects related to the back-end of the nuclear fuel cycle (spent-fuel storage and disposal). These include thinking about how we might coordinate across national lines to better internationalize and regionalize nuclear-waste storage; strategizing about removing nuclear materials from plants and across national borders; and developing a better understanding of the economics of dealing with nuclear waste in the international context. In addition to the back-end of the fuel cycle, we have also been focusing on nuclear safety, nuclear liability, and nuclear terrorism – in particular, the issue of insider threats.

One thing that we recognized early on is that it is not a great idea to tell other people what to do. The individuals and groups that we deal with are already very savvy about the problems associated with nuclear energy. A very important element of our approach, therefore, has been to involve the stakeholders in the countries that we are visiting in the discussions. In fact, many of our publications are authored or coauthored by individuals from the countries we have been working with: we are not the only ones at the table speaking.

Much of the work in the area of nuclear security has historically focused on what I like to call the “utopian state.” This work often founders on the problem of how we get to the world as we would like it to be. With this in mind, we have recognized the need to focus on the process of “getting there.” What does this mean in practical terms? We have been convening regional conferences with key stakeholders: civic leaders, politicians, academics, and individuals in the private sector and in industry. We have also been hosting policy briefings, consulting with government officials in various countries, and facilitating the involvement of the international nuclear industry in the conversation. We have commissioned publications coauthored by stakeholders in the regions we have visited, as I mentioned before; we have also been fostering relationships with the academic community in those regions.

Our work has led to the publication of two issues of Dædalus and a number of occasional papers on topics ranging from disarmament and nonproliferation to the back end of the nuclear-fuel cycle and the nature of reactors themselves.

Of our three publications from the last year, only one of them was written by one of us (this was an occasional paper coauthored by Scott Sagan and Matthew Bunn, called A Worst Practices Guide to Insider Threats: Lessons from Past Mistakes). The other two were written by experts from our target regions. For example, an entirely new subfield in nuclear security studies was explored by Mohit Abraham, a constitutional lawyer in India, who wrote for us about India’s changing perspective on nuclear liability. Liability has generally been placed on the operator, and, by extension, on the government to provide backstop. India is now considering extending liability to the companies that actually produce the equipment. You can imagine the reaction of the nuclear industry to that change.

2014 was a very busy year for our program. We had a meeting in Bali to which we invited stakeholders from all the ASEAN countries, as well as Japan, Korea, and China. We ran a workshop on insider threats here in Cambridge, Massachusetts. We also held a workshop for journalists in the Middle East, discussing nuclear-related issues the region faces. The Worst Practices Guide to Insider Threats has actually become a training manual at United States weapons labs, which was surprising and excellent news. That publication was also highlighted at the World Institute for Nuclear Security (WINS) workshop in Vienna in September 2014. The work I have been guiding on the back-end of the nuclear fuel cycle has led to discussions with the U.S. State Department and nuclear industry leaders.

We traveled to Abu Dhabi in January 2015, primarily to follow up on our first meeting. During that previous visit, the government was deciding which corporate team would design and build their plants; now the chosen team, led by a South Korean group, is actually in the process of building them. We will be in Seoul in February; in Chicago in March; and finally, in May, participating in the Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference. Finally, we will be participating in an international conference on insider threats when we release our book on the subject. It is a busy schedule, but we have a great time.

I would like to end my remarks by repeating Steven Miller’s sentiment: the Academy is a great venue to do interesting things. It has amazing pulling power to engage the world in ways that we – sitting in our academic institutions – often do not, so I highly encourage you to participate.

Humanities, Education & Social Policy

The Commission on the Humanities & Social Sciences

Carl H. Pforzheimer III

Carl H. Pforzheimer III, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2002, is Treasurer of the Academy and the Manager of Carl H. Pforzheimer & Co. LLC and of CHIPCO Asset Management, LLC. He is a member of the Academy’s Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences. He serves as a member of the Academy’s Board of Directors, Council, and Trust.

In 2010, a bipartisan group of Congressional leaders called upon the Academy to examine the importance of the humanities and social sciences to American democracy and competitiveness. They asked the Academy to consider this question: “What are the top actions that Congress, state governments, universities, foundations, educators, individual benefactors, and others should take now to maintain national excellence in humanities and social-scientific scholarship and education, and to achieve long-term national goals for our intellectual and economic well-being, for a stronger, more vibrant civil society, and for the success of cultural diplomacy in the twenty-first century?” To address this question, the Academy in 2011 established the Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences. The Commission brought together leaders from the sciences, business, public affairs, social sciences, humanities, and the arts to advance a new conversation about the importance of these disciplines to the nation’s intellectual and economic strength, its public institutions, and its civil society.

The Commission’s report, The Heart of the Matter, was released on June 19, 2013. The Commission was chaired by Richard Brodhead, President of Duke University, and John Rowe, Chairman Emeritus of Exelon Corporation; it included fifty-two other leaders from academia, business, the arts, and public affairs. As part of the rollout of the report, the Commission oversaw the creation of a companion film created by Ewers Brothers Productions in consultation with two Commission members, Ken Burns and George Lucas. The film has been viewed over thirty thousand times online and screened at large meetings across the country, even in K–12 classrooms.

The goal of the Commission was to push the public conversation about education to reintroduce the humanities and social sciences into a dialogue that had been focused almost entirely on the STEM disciplines. To that end, approximately one hundred thousand copies of the report have been distributed in hard copy or downloaded from the website. The Heart of the Matter has been the subject of dozens of op-eds, including fifteen by Commission members. Nearly three hundred articles have been written about the report. Many other major news outlets, including The New York Times, The Atlantic, Slate, the Huffington Post, NPR, and PBS, have covered the Commission’s work in detail – Richard Brodhead even had a memorable appearance on The Colbert Report.

Commission members and American Academy staff are working with the Federation of State Humanities Councils and the Institute of Museum and Library Services to sponsor Heart of the Matter events in at least fifteen states. In fact, we are working with anyone who is interested in meaningfully extending the dialogue. We even structured the Commission website to mirror the sites of political campaigns so that visitors can quickly and easily request materials and register for email updates.

Policy-makers have taken note of our activities. In January 2014, six Senators and six Commission members met for dinner in Washington, D.C., to discuss next steps. Since then, members of both the House and the Senate have expressed interest in pursuing some of our recommendations, most notably those on international education. For example, in December, Representative Rush Holt of New Jersey suggested an expansion of President Obama’s proposed STEM Master Teacher program to include other disciplines in addition to math and science, based on a recommendation from The Heart of the Matter. In fact, the first page and a half of the bill was lifted directly from the Commission report.

I suspect that part of the Commission’s success will be due to the expanding network of partnering organizations working to push the Commission agenda forward. These include the National Humanities Alliance, the Federation of State Humanities Councils, Phi Beta Kappa, the American Association of Universities, the Association of American Colleges and Universities, and the Chicago Humanities Festival, as well as colleges and universities across the country. Earlier, Robert Rosner made a comment about preaching to the choir, which is something about which the Academy remains mindful in its endeavors. I would say that, although all of the organizations that I just mentioned are part of the choir, there are many more concerts being planned than ever before.

The Commission on the Humanities & Social Sciences

Karl W. Eikenberry

Karl W. Eikenberry, a Fellow of the Academy since 2012, is the former United States Ambassador to Afghanistan and retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General. He is currently the William J. Perry Fellow in International Security at the Center for International Security and Cooperation and a faculty member of the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center at Stanford University. He is a member of the Academy’s Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences.

The Charter of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, written in 1780, says that “The end and design of the institution is to cultivate every art and science that may tend to advance the interest, honor, dignity, and happiness of a free, independent, and virtuous people.” I think that this very aptly describes what the Heart of the Matter report has done in promoting the study, research, and practice of the arts, humanities, and social sciences in the United States.

One of the most unusual aspects of this report is that, unlike most, it was not prepared, issued, and then promptly put on everyone’s shelf. Instead, it has truly served as a starting point for an ongoing national conversation about the issues that it raises and the possibilities that it explores. I have had the honor of serving on this Commission and have contributed to several events since the publication of the report over the past eighteen months, including at the National Humanities Alliance annual meeting in 2013; Carnegie Mellon University; the Chicago Humanities Festival; the British Academy of Humanities and Social Sciences in London; and a gathering at North Carolina State University that was attended by the Chancellor of the University, the Duke University president, and Congressman David Price. Truly, each one of these experience has been among the most rewarding of my life.

Let me offer three thoughts, then, to those of you who may be interested in contributing to this enterprise.

First, in terms of considering the comparative advantages each one of you might have to offer, it is useful to think in terms of the project’s overarching goals. These include: educating Americans in the knowledge, skills, and understanding they will need to thrive in a twenty-first-century democracy (this is very much in the tradition of Judge Louis Brandeis’s famous maxim that the most important political office in this country is that of private citizen); fostering an innovative, competitive, and strong society; and preparing the nation to lead in an interconnected world.

Second, the report’s areas of emphasis are very comprehensive and offer the possibility for any Academy Fellow to engage in areas corresponding to his or her strengths and interests. This could be K–12 education; two- and four-year colleges; research; cultural institutions and lifelong learning; or international security and competitiveness. Given my own background in the military and diplomacy, I have elected to focus my public presentations primarily on the last topic: maintaining the nation’s leadership in a globally interdependent world.

Third, and last, some specific recommendations:

Let the Committee – in particular, Program Director John Tessitore – know of your desire to contribute if you wish to do so. John does a terrific job of letting Fellows know about events of possible interest either nationally or in their own backyard.

Look for opportunities to create events, either in collaboration with others or on your own.

As two other speakers mentioned today, it is important that we do not waste time lecturing the converted, but instead engage with scientists, engineers, and mathematicians; businesspersons; and those in the executive and the legislative branches at federal, state, and municipal levels. And you’ll usually find very receptive audiences among those individuals.

Include instrumentality in your arguments for the arts and humanities. Of the top leaders of one major Silicon Valley IT company, eight majored or minored in the arts or humanities either as undergraduates or graduate students. The list includes a music major, a drama major, a dance minor, and an individual with a master’s degree in philosophy from Oxford University. It is important that our Committee continues to enlist individuals whose professional success was helped by their humanities background and to make their voices heard. This is crucial because parents and children in our country are very concerned about whether taking courses in literature, drama, and philosophy would help them in making a living in the United States of America today and over the next several decades.

Draw upon your own life experiences in making your arguments. When I speak publically, I discuss the advantage that my years of liberal arts education at West Point, Harvard, and Stanford provided me during my military and diplomatic career. I talk about the importance of my Chinese language studies and about the many skills I acquired as a result of my arts and humanities curriculum: analytical thinking; a rigorous grounding in ethics, writing, creativity, and problem solving. I also talk about my time as an ambassador in Afghanistan, where some of our most cost-effective development programs were focused on the arts and humanities. For example, one of our most valuable staff members was the embassy archaeologist, who led two projects in Afghanistan to help rebuild the Afghan National Museum and restore the famous Citadel of Herat in Western Afghanistan. Recounting vignettes such as these can be very powerful.

Use the Academy resources. The Humanities Report Card and reports on government and private expenditures in the arts and humanities are available online.

Finally, recognize the need to communicate in ways that reach today’s younger generation. As you heard, Duke University President Richard Brodhead had a superb appearance on The Colbert Report. I told him at the time that I thought it was probably tougher volunteering for duty on the Colbert Report than in Afghanistan! So you must get outside of your comfort zone if you want to reach the younger generation.

The Humanities Indicators

Norman M. Bradburn

Norman M. Bradburn is a Senior Fellow at the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago, and the Tiffany and Margaret Blake Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in the faculties of the Department of Psychology, the Harris School of Public Policy, the Booth School of Business, and the College at the University of Chicago. He was elected a Fellow of the Academy in 1994. He is the Principal Investigator of the Academy’s Humanities Indicators Project.

In 1997, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences began exploring the feasibility of a Humanities Indicator project that would publish up-to-date data on the humanities in the United States. With generous support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, work on a prototype of the Indicators began in 2006, and the project became fully operational in 2008. The Humanities Indicators takes as its model the long-running Science and Engineering Indicators released by the National Science Foundation. The Science and Engineering Indicators have become the gold standard for data underlying an array of policy debates and have driven much of the conversation over the past two decades about the needs of the STEM community. The need for a humanities equivalent was apparent.

What do we mean by Humanities Indicators? Indicators are quantitative, descriptive statistics that chart trends in some phenomena of interest. They are policy-neutral and are updated regularly. They describe a situation but do not explain anything. They answer “what” questions, not “why” questions, so their interpretation is not always straightforward; their data may mean different things to different observers. If done well, they provide a reference against which arguments for changes in reality can be tested, and a common starting point for arguments about the nature or rate of change in some phenomenon of interest.

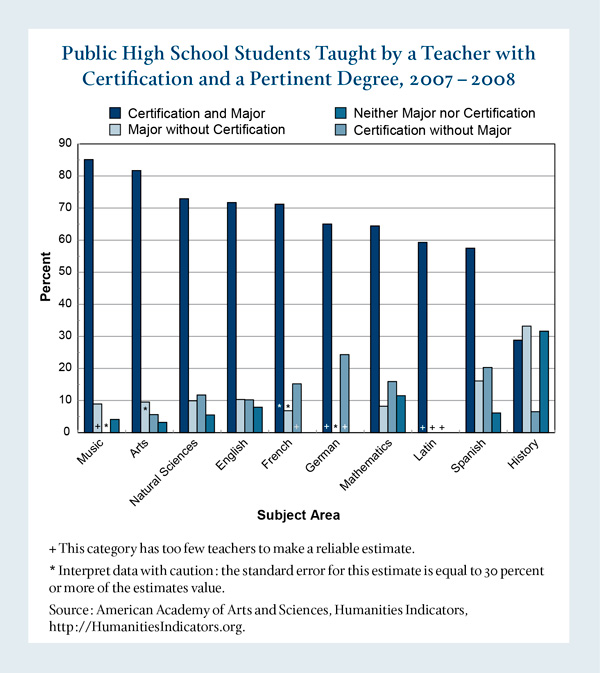

What questions about the humanities do we need answers to? We posed this question to people active in various aspects of the humanities. For many of these questions, we have no answers at present due to a lack of data. However, we were able to distill the many viable questions down to a manageable set of five topics. These topics are: primary and secondary education; undergraduate and graduate education; research and funding for the humanities; the humanities workforce; and humanities in American life. The Indicators site currently contains 76 topics and over 270 graphs and tables of information organized by these five categories. The website is updated regularly as new information becomes available.

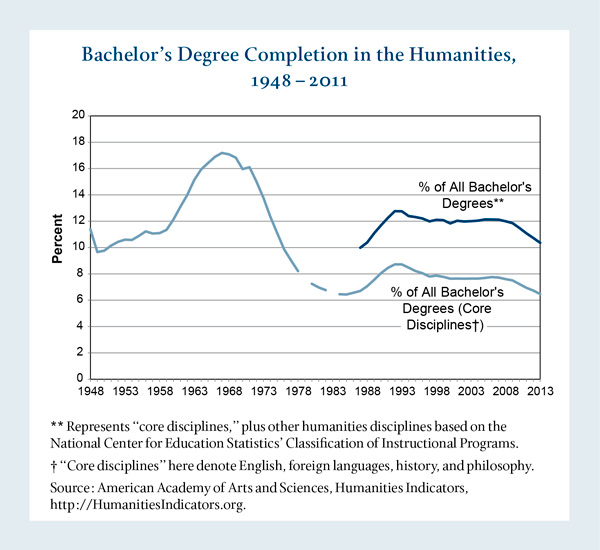

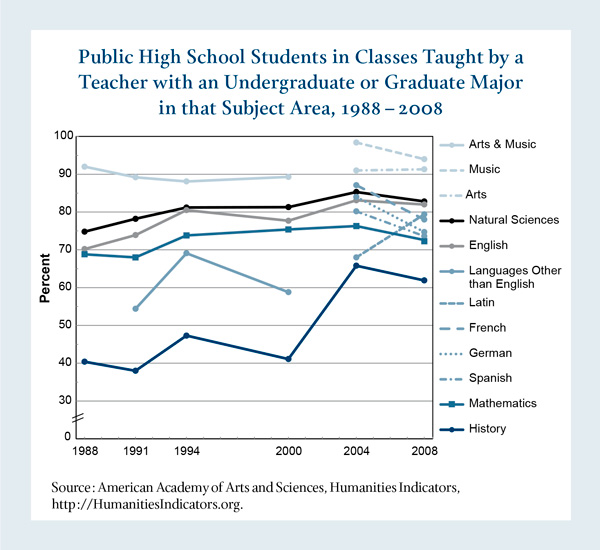

The Indicators have been heavily used, sometimes leading to vigorous controversy. For example, Harvard University used our data last year in a report on the humanities. The Wall Street Journal picked up that data and created a graph to start a conversation about the collapse of the humanities as signaled by the number of majors. But if you look at the data closely, you will see that the dramatic decline they trumpeted occurred in the 1970s and 1980s (see Figure 1). The gradual decline that has taken place over the past four decades is interesting, but humanities majors only dropped one percentage point after the onset of the 2008 recession – hardly a sudden collapse. Furthermore, the peak from which the humanities fell in the 1970s was an unusually high point of engagement. The graph used by The Wall Street Journal and Harvard left out a second line (shown in dark blue in Figure 1), which represented our attempt to account for students in other disciplines that certainly count as the humanities (such as area studies) but which are outside of the “core of four” humanities disciplines (English, foreign languages, history, and philosophy).

| Figure 1 |

|

The Holy Grail of photovoltaic modules has been 50 cents per watt (see Figure 2). The price is now about 75 cents. Over five years, we have seen an enormous drop in these costs, and deployment has been going up; it is still small, but it is going up. Today, a utility can build a large photovoltaic farm for about $1.80 per watt, which, once you do the arithmetic (assuming a 20 percent capacity factor and a 5 percent cost for capital), works out to about 5 cents per kilowatt-hour – which is very competitive.

| Figure 2 |

|

| Figure 3 |

|

These are just a few examples of how the Indicators afford us the ability to examine things to which little public attention has been paid. In this and many other ways, they can inform our discussion about the current health of the humanities. I invite you to explore them more fully and to begin drawing your own conclusions and starting your own conversations.

The Lincoln Project: Excellence and Access in Public Higher Education

Robert J. Birgeneau

Robert J. Birgeneau, a Fellow of the American Academy since 1987, is Chancellor Emeritus and Silverman Distinguished Professor of Physics, Materials Science, and Engineering and Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley. He is Cochair of the Academy’s Lincoln Project.

We launched the Lincoln Project in October of 2013. For our first year, we were largely in data-collection mode, trying to understand what the issues are and collecting quantitative information, some of it analogous to the Humanities Indicators data, which has been a valuable guide for us. Our practice of collecting and interpreting data will go on continuously, but we are about to shift our strategic emphasis somewhat, with the aim of not just producing Academy publications but also pursuing a political advocacy strategy. The 2016 election will therefore be guiding our schedule from this point forward.

Our project is named for President Abraham Lincoln, to commemorate his role in signing the Morrill Act of 1862, which laid the groundwork for the United States’ unparalleled public university system. It is clear that U.S. universities – especially public research universities – are increasingly challenged, and we formed this Committee to address that problem. The Academy is the ideal venue for the project because of the extraordinary breadth of the membership, of which we have taken full advantage.

The Lincoln Project is cochaired by Mary Sue Coleman, former President of the University of Michigan; and me, Chancellor Emeritus of the University of California, Berkeley. Our respective institutions are unfortunately model representatives of the dire situation of state disinvestment in higher education. Our Committee members were deliberately selected from a very broad array of backgrounds. We have enlisted university leaders, both current and past, from both public and private universities across the country. We have a significant number of business people as well as representatives of learned societies. Also on the Committee are several former politicians, including Kay Bailey Hutchison, former U.S. Senator; Gray Davis, former Governor of California; Phil Bredesen, former Governor of Tennessee; and Jim Leach, former Iowa Congressman. Finally, and very importantly, we have engaged experts in quantitative research and analysis as well as communications in order to help combat the extraordinarily high level of misinformation about higher education. To make our case to the public, we need to have believable and objective data and an effective communication strategy.

The first question that one might ask is how American universities are doing. One way of addressing this is to look at international rankings of research universities. My personal favorite among those is carried out by Shanghai Jiao Tong University, which ranks institutions on their excellence in the social sciences, science, and engineering. Their ranking methodology is data-based: its metrics include journal publications, citations per faculty member, and distinguished academic honors won by former students and current faculty members. You can agree or disagree with the Shanghai Jiao Tong methodology, but at least its metrics are quantitative, transparent, and understandable.

If we look at the most recent Shanghai Jiao Tong ranking, which came out in September 2014, quite a few American flags are visible in their top-25 list. Manifestly, American research universities, both public and private, continue to do extraordinarily well, which leads some to ask, “Is there really a problem?” I do not have to tell any of my friends working in private universities that their institutions now seem much more fragile than they once did, especially after the 2008 recession. But for public research universities, the situation is far direr. Across the United States, on average, funding per student has declined dramatically in those institutions and tuition has risen correspondingly. The decline in funding per student shows no sign of slowing down. Recently, I was at one of our great state universities giving a physics colloquium. I met with the university president, who informed me that their administration is now including in its budget projections one scenario in which state funding goes to zero! Is a public university still public if the state funding is zero?

Clearly, we have a very serious challenge on our hands. I am often quoted as saying that we have many great universities in the United States, both public and private, but we must have both. The Bay Area already has Stanford. We do not need a second Stanford in the form of a privatized Berkeley – we need a public Berkeley. Both institutions are important, but they play very different roles societally.

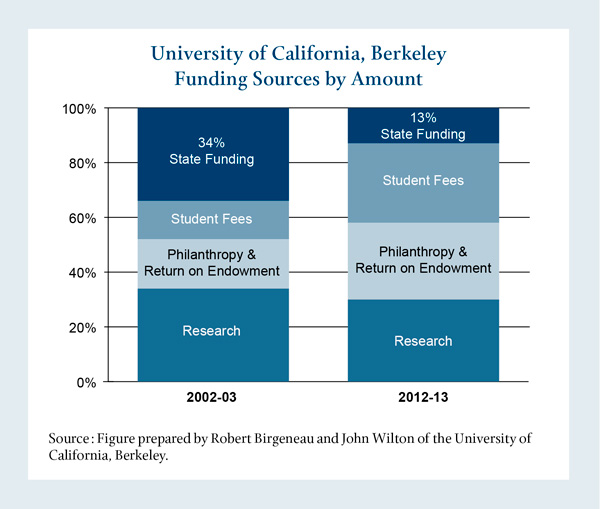

Berkeley has turned out to be an extreme example. In the 2002–2003 academic year, just before I began my tenure as Chancellor of the University, state funding represented just over one-third of our budget (34 percent; see the dark blue bar in Figure 4). During my time as Chancellor of UC Berkeley, state funding descended to a low of 10.5 percent of our total budget. Superficially, it appears that the situation has improved somewhat, because state funding has since risen to 13 percent. However, this is only because other funding sources, measured in real dollars, have dropped, not because state funding has gone up significantly. For example, student fees have been frozen for several years. All of the other funding sources – research, philanthropy, and student fees – now dwarf state funding (Figure 4).

| Figure 4 |

|

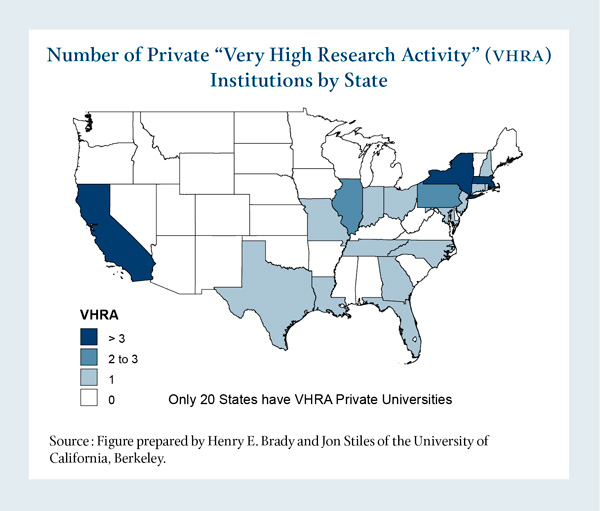

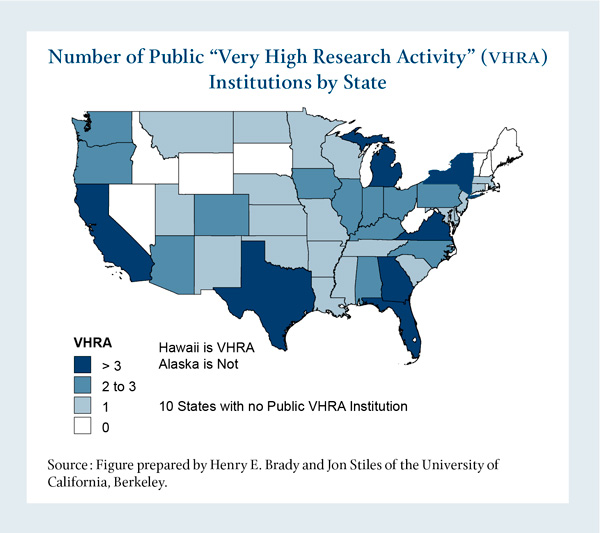

Now let us look at the distribution of the elite public and private universities across the country (Figures 5 and 6). When Henry Brady, Director of the Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley, first showed me these data, I was astounded. There are only four states in the United States that have two or more elite private universities; another fourteen have one elite private university. In many cases, those private universities educate quite a small number of undergraduate students relative to the flagship public universities in the same states. The data show that the majority of states in the United States are without significant private research universities. Indeed, some highly educated states, such as Washington, Michigan, and Colorado, are left out completely.

| Figure 5 |

|

| Figure 6 |

|

The flagship public research universities (members of the Association of American Universities, or AAU), on the other hand, educate a large fraction of the most talented university-attending population in the vast majority of the country.

If we include not just the AAU-level institutions, but also high-research-activity universities, of which many are private, the number of states with high-level private research universities goes up a bit. Even with these added, however, the vast majority of states have no private research universities, either of AAU caliber or of the next level down. If we look at the public universities of the same caliber, however, then we can see that every state in the country has a significant public research university. So, clearly, maintaining the health of these institutions is of paramount importance.

Another salient fact is that low- and low-middle-income students constitute 44 percent of the student body in public research universities, compared with 29 percent in private universities. Public universities act as the conduit into mainstream society for underprivileged but extremely talented people who will form the backbone of this country going forward. This is particularly true for underrepresented minorities: Latinos, African Americans, and Native Americans are overwhelmingly being educated in our public universities. From the absolute numbers for undergraduates, we see that the elite private universities have about five hundred thousand undergraduates, while the flagship public universities have close to three million. Clearly, America’s educated and skilled workforce is highly dependent on the health of our public universities.

These are just some of the conclusions we have reached so far in the Lincoln Project. The data make evident that maintaining our public research university system is of the utmost importance. In addition to spreading awareness, we also wish to address a number of important issues going forward. First, one might ask who is missing entirely in the public research university funding picture? We are the only country among our economic competitors where the federal government does not contribute directly to the operations of our great public research universities. In every single other country with whom we compete, the federal government understands that the health of the public research university system is critical to the country’s future as a whole. Washington needs to step up!

My second point – and perhaps a more controversial one – is that industry is by and large not making its fair contributions to education through the tax system. Corporations across America continuously hire graduates from our leading public universities while having contributed minimally to the cost of their education. This has to change. There are many ways that this could happen. I would like to conclude with a proposal that is specific to California but could be easily generalized to other states. If high-tech corporations in California were simply to repatriate annually 1 percent of their revenues which they are holding off-shore and donate those to the University of California and the Cal State universities, this would solve permanently the financial problem for public higher education in the state of California. My one extended conversation with a Congressman deeply committed to education indicates that this is by no means an irrational suggestion.

The Lincoln Project: Excellence and Access in Public Higher Education

David B. Frohnmayer

David B. Frohnmayer, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2002, is President Emeritus of the University of Oregon. He joined Harrang Long Gary Rudnick P.C. as “of counsel” in 2009. Previously he served as Oregon Attorney General, in the Oregon House of Representatives, as legal adviser to the University of Oregon president, and as Dean of the University of Oregon School of Law. He serves as a member of the Academy’s Board of Directors and as an advisor on the Academy’s Lincoln Project.

Public research universities are extraordinarily important institutions: they have provided great opportunities for the United States, and for individuals in this room who credit public higher education with their chance to live the American Dream. However, as Robert Birgeneau just shared with you, these institutions are currently dangerously fragile.

The Lincoln Project comes from the same wellspring of the Academy’s engagement as the other great efforts of which you heard this morning. I mentioned that these institutions are important. It should also be understood explicitly that they are a national public good and that while they are state-directed, they serve national and, indeed, international purposes. Their noble historical tradition extends back to the first Morrill Act. They enroll millions of students and provide them with quality higher education. They are research engines in their own right. They are also vastly significant regional economic powerhouses – a largely overlooked fact that we hope to highlight in our work.

Notwithstanding public universities’ great impact, their storied origins, and the sheer quantity of students that they engage, their future success is precarious. There is no federal system of higher education. As Bob pointed out, quite shockingly, we are the only nation in the developed world that does not have a national policy in place to support public higher-education institutions. Competing demands on state budgets have been devastating. Medicaid, prison expansion, and voter-driven tax reductions are just a few policy priorities that, at least in my state of Oregon, have powerful political constituencies. In some cases, the withdrawal of state budget support due to the whole of these competing interests has been close to catastrophic. This gives currency to a shopworn adage – at least among public-university presidents – that public universities have gone from being state-supported to state-assisted, then state-located, and finally state-molested.

Many of these institutions do not have the same tradition of private philanthropy as private institutions, and they certainly do not enjoy the same wealthy endowments. So the pressures of the current moment are even more demanding on them. Maintaining accessibility means that they do not, politically or even ethically, have the same capacity to raise tuition levels. This creates enormous dilemmas; in both public and private institutions these days, an enormous amount of the subsidy of basic research actually comes on the backs of undergraduates, from the tuitions that they and their families pay.

Significant data have been collected, and the Lincoln Project will use this information to make a data- and evidence-based case for the public university to a degree that is unusual for recent years. We want to enlist the support of any Academy Fellows who wish to work with us on this project, because our conclusions are still being formulated. Even at this early stage, however, we foresee seven or eight points that will be part of the Academy’s report on this project.

First, we will be doing a lot of demystification. There is an enormous amount of misinformation and overgeneralization about the levels and degree of student debt: where it is, how much there is, and how much of that is offset by financial or scholarship assistance. I think that deconstructing myths about debt – and some of the other stereotypes about higher education that command our current political template – is extraordinarily important.

Second, it is critical that we find strategies to enlist business and industry. We need private-sector leaders – not merely the shareholders of their corporations – to be our champions. Third, we have discussed potential contours of a twenty-first-century approximation of the Morrill Act of 1862, which established public land-grant universities. Fourth, we will build on the Restoring the Foundation report, continuing its project of encouraging research much more comprehensively.

Fifth, we will explore incentives to philanthropy, whether through the Internal Revenue Code or other mechanisms. Sixth, we will call for the reinvigoration of the state’s active role in maintaining the public research university as an essential piece of the American Dream. Seventh, we will underscore changing student demographics, because they will have a significant impact in the long run. In many states, the college-age population is either falling or predicted to fall; the ethnicity and preparatory educational backgrounds of students also continue to shift. While demographics may not be destiny, demography is certainly a powerful tool for anticipating the educational needs of the next generation of students in the higher-education opportunity. Finally, but not exclusively, we hope to uncover and highlight best practices that might be transferrable from one institution or region to another.

We hope that our pursuit of these essential and challenging questions will make this a project worthy of the Academy’s efforts and of the efforts of so many others in the past who have committed themselves to ensuring the accessibility and excellence of public education.

© 2015 by Neal Lane, Nancy C. Andrews, Barbara Kates-Garnick, Seth Mnookin, Steven E. Miller, Scott D. Sagan, Janne E. Nolan, Robert Rosner, Carl H. Pforzheimer III, Karl W. Eikenberry, Norman M. Bradburn, Robert J. Birgeneau, and David B. Frohnmayer, respectively.