How CPVs Would Work

This section lays out a policy framework for CPVs designed to facilitate the arrival of new immigrants in places where they do not currently choose to go in significant numbers. The working group presumed that legislation will be required to create CPVs but that no legislation can account for all the administrative decisions necessary to implement such a complicated program. Enabling legislation, therefore, ought to contain clear statements that Congress intends the supervising agency or agencies to adapt the visa program to changing circumstances, including the possibility that the program works differently in practice than anticipated. Throughout this report, we have identified questions that will need to be resolved by the agency or agencies charged with overseeing the program.

In developing the CPV framework, we sought at all points to promote two principles for both visa recipients and communities: agency and flexibility. We prioritized agency in recognition of autonomy, choice, and consent as central American values, concluding that the visa program should allow communities to opt in and respect the preferences and personal freedoms of visa recipients. We prioritized flexibility in recognition of the likelihood that, once implemented, a program of this kind would need to evolve. Rigid rules would do a disservice to both visa recipients and their host communities. The rules and operational details we propose below should be seen as suggestions; other configurations may also work well, provided they retain the flexibility of the program and respect the agency of participants.

Steps to Creating CPVs

Community Eligibility

The first step to setting up CPVs involves identifying the communities eligible to accept visa recipients. Eligibility should be determined based on the state of local economies. Traditional geographic units, such as counties or municipalities, will not adequately identify target communities. Some counties are extremely large. Some are sparsely populated. Crucially, county borders do not reflect economic borders in a meaningful way. Municipalities, meanwhile, do not include rural areas.

The working group proposes that the CPV program rely on the Commuting Zone (CZ), which represents the unit of geography that offers the best approximation of the shape and state of a local economy. CZs were developed by the federal government in the 1980s and are based on census data on individuals’ travel to and from their jobs. Because CZs utilize people’s movement in the course of their daily lives, they offer a better geographic reflection of local economies than traditional political boundaries. CZs for 2020 were built by geographer Christopher S. Fowler, whose analysis divides the nation into 583 CZs. Most CZs are located entirely within a single state, though some cross state lines.13

We further propose relying on the following metrics to determine community eligibility:

Population growth

Prime age (25–54) labor force participation rate

Median income growth

Local cost of living

The first three metrics serve as proxies for economic performance. A community that is losing population will, almost by definition, struggle economically, either in the short or the long term. Population loss means that even if labor force participation and income growth remain strong—or especially if they remain strong—the community in question will face a dearth of eligible individuals to fill open jobs. Any community that is losing population and has low income growth for median-income earners is almost certainly struggling. Without outside intervention, this community may be headed for a downward economic spiral, as the loss of population will further depress incomes, which will drive more people to leave, and so on.

We used the following formula to determine CZ eligibility (see Appendix B for a more detailed methodology). First, we tabulated the median income growth, prime age labor force participation rate, and population growth rate for each CZ using county-level data, which was weighted according to county population. The median income growth and labor force participation measures were combined into an aggregate measure. We then built a distribution of CZs along both the population growth measure and the combined labor force/income growth measure. Any CZ that scored above the eightieth percentile on both the population growth measure and the labor force/median income growth measure was labeled ineligible. By our metrics, these places are already thriving—many because they are already immigration hubs—and would not require place-based visas to attract new immigrants. On the other side of the distribution, any CZ that scored in the bottom twentieth percentile of both measures was also made ineligible. Some of these CZs are so challenged economically that only a large infusion of immigration—one beyond the scope of the CPV program—would change their economic trajectory. Many of the other recommendations in the Academy’s CORE report, Advancing a People-First Economy, would aid these places, including proposals focused on banking, housing, healthcare, broadband access, social safety nets, workforce development, and place-based anti-poverty programs. It also would be contrary to the best interests of the visa recipients to be drawn to a sparsely populated community where they do not have a realistic chance for economic security or opportunity.

Finally, CZs with a high cost of living were labeled ineligible. Population loss in these counties is likely related to this cost of living, not stagnant economic growth. Using the Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator, we used population-weighted county-level data to determine the cost of living in every CZ for a two-parent, two-child household. The top 20 percent of CZs by cost of living were made ineligible for CPVs.

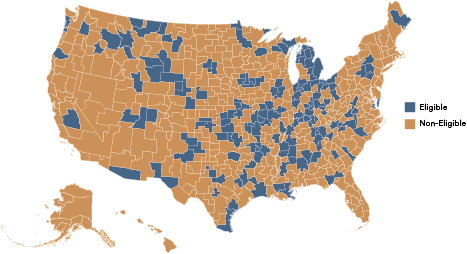

Commuting Zones by CPV Eligibility

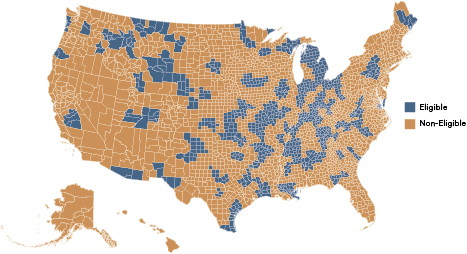

Counties by CPV Eligibility

Under our proposed criteria, 168 out of 583 CZs would be eligible to participate (28.8 percent of the total). Eligible CZs account for 30 percent of all counties and 19 percent of the American population (using 2020 population data). Thirty-nine states include at least one CZ.14

Overall, eligible counties had lower per capita GDP than ineligible counties (nearly 25 percent lower in 2020). They also had lower levels of overall well-being, as measured by the CORE Score, a product of the Academy’s Commission on Reimagining Our Economy. The Score is a 1–10 measure of well-being in eleven annual county-level measures across four categories: economic security, economic opportunity, health, and political voice. In 2023, eligible CPV counties had an average CORE Score of 5.33, lower than the national average (5.61) as well as the average of noneligible counties (5.68). Eligible counties averaged lower scores than noneligible counties across all four categories.

Eligible communities include a range of places. Some have relatively robust labor participation rates or median income growth, but a lack of proportional population growth signifies a dearth of personnel to fill available positions and help the community continue to thrive. Eligible communities include both rural and urban areas, and the most populous places eligible by our formula are the CZs that include the cities of Detroit, Michigan; Cleveland, Ohio; Tucson, Arizona; Fresno, California; and St. Louis, Missouri. While some of these cities are already immigration hubs, in general the CZs eligible in our formula have a higher percentage of their population consisting of people born inside the United States compared to ineligible CZs (92 percent for eligible compared to 83 percent for ineligible). Places that would be qualified to host CPV recipients are, generally speaking, not places where immigrants are already choosing to live.

Community Opt-In

No community will be required to participate in the CPV program. The program as a whole should be supervised and directed by a federal agency, as explained in more detail below. But local residents and leaders should determine for themselves that their community has the need and the capacity for the arrival of immigrants. Local leaders will have the best sense of the types of job openings available in their area and the types of workers who would best help their community thrive.

Though CZs, as measures of local labor markets, offer the best metric for defining areas of eligibility for CPVs, such zones are not political units. CZs have no mayor or governing commission and thus no institutional entity that could apply for the program. As a result, applications to participate in the visa program should be made by county, city, municipal, or tribal officials who represent an area located within an eligible CZ. Ideally, these should be officials who answer to voters, to ensure that the decision to participate is subject to democratic accountability. Because multiple political units exist within any given CZ, more than one application from a CZ may be viable. For example, Wayne County and Oakland County, Michigan, fall within the same eligible CZ. Officials from each county would be able to apply to the program as they saw fit. Furthermore, within each county, multiple cities or towns could endeavor to apply. Efforts to coordinate applications across units should be given consideration as the program develops.

The entities that submit formal applications to the program will differ across locales. Some counties or municipalities have robust governmental systems that could apply directly. Others may want to designate this responsibility to a local governmental or nongovernmental body. A nonexhaustive list of possible organizations includes:

Workforce Development Boards: Regional entities focused on economic and educational development. There are 590 such boards across the country, varying widely in jurisdictional size.15

Regional community and economic development organizations: Quasi-governmental organizations focused on economic planning and development. These bodies are variously known as Regional Development Organizations, Councils of Government, Planning and Development Districts, Regional Planning Councils, Area Development Districts, or Local Development Districts. The National Association of Development Organizations has a membership of more than five hundred such entities across the country.16

Tribal governments: Though legally more analogous to states than cities or counties, Native American reservations represent major hubs of regional employment and economic development in certain parts of the country.

If a county or local government chooses to designate another entity to apply for CPVs on its behalf, local officials should select an entity whose primary mission is to advance the well-being of the people within their jurisdiction and is attuned to the state of the local labor market. Ideally, these entities should include a wide variety of community figures—rather than, for example, solely business leaders—and should not have a political affiliation. Applying entities should also strive to solicit input from the public as they draft the application. Wherever possible, they should consult with refugee resettlement organizations or other bodies that have experience with immigrant relocation to the relevant community to ensure they have a complete sense of the financial prospects of the new immigrants. Counties and municipalities should ensure that only one entity applies on their behalf, and the supervising federal agency should set up a certification process to designate an official applicant for each interested locale.

The Community Application

Only the federal government can issue visas. The CPV system, therefore, must be designed to enable communities to indicate the needs of their local labor market to the federal government. We recommend that CPVs be overseen by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), in consultation with the Department of State where relevant. USCIS would review applications from communities, direct the process of allocating and issuing visas, and then issue visas.

Many details about this application should be left up to USCIS. Important principles that should guide the drafting of the application forms include:

The CPV program should be open to workers from a wide range of categories. The communities eligible to participate in the CPV program are heterogeneous. Some will seek people with advanced degrees or particular expertise. Others may need to fill positions that do not necessarily require any or much advanced training, including in fields such as agriculture and manufacturing. Applying entities should be able to note the type of workers they are seeking to invite or should be able to select from a supplied list of options.

Some county or local governments may lack the bureaucratic capacity to prepare an application. They may not even have the ability to designate another organization to apply or may be the only eligible entity in their area. This lack of capacity should not be a barrier to participation. The enabling legislation for CPVs should delineate precisely how counties can designate local entities to apply to participate while also offering a shorter, simpler application for counties to apply to USCIS for help completing the fuller application. This would ensure all eligible counties are actually able to participate.

The application should require communities to demonstrate that potential immigrants are not being brought in for the purposes of undermining incumbent workers or loosening tight, worker-friendly labor markets. The applying entity should provide evidence that the community is unable to satisfy the needs that would be served by the types of workers the community is seeking. Any such requirements could parallel, but should be less strict than, those that apply to other temporary worker programs, such as H-2A (Temporary Agricultural Workers) and H-2B (Temporary Non-Agricultural Workers) visas.

The application should include space to indicate how many visa recipients the community hopes to receive. The number of visas a community can apply for should be capped and proportional to the county’s population and the total number of visas the enabling legislation authorizes USCIS to distribute.

The Individual Visa Applicant

The federal government should place limits on who can apply for a CPV. Only those between the ages of eighteen and forty-nine should be eligible, to reflect the program’s goal of boosting the local labor force. In addition to those outside the United States, individuals already in the country on a temporary visa—including Temporary Protected Status—should be eligible to apply, as should individuals with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and parole statuses.

Applicants should not be required to have already received a job offer as part of their application. Such a requirement would reduce the flexibility of the program for both communities and visa recipients. Regardless of whether they are the entity that applies for CPVs, local political, business, and workforce development groups, as well as local refugee or immigrant resettlement organizations, should seek to identify job openings for visa recipients to ensure quick transitions into the local labor market.

Like the communities themselves, potential visa recipients would opt into the program by applying, either through the Bureau of Consular Affairs if they are abroad or USCIS if they are already located in the United States. The application should resemble typical work visa applications and should include relevant security screening. The agency can attach an application cost to the program, and the fee should remain in line with that for other immigration programs, such as H-1B or Conrad 30 J-1 visas. These fees can help defray the costs of administering the program at the federal level.

Matching Communities and Applicants

A key part of the CPV process will involve matching the communities that opt into the program with applicants from around the globe (and within the country). By necessity, this process should be overseen by USCIS. The agency should develop its own process to match communities with applicants and to incorporate community input into the matching process.

Visa Portability

Strict policing of the movement or residence of visa holders would be impractical, and doing so would run contrary to the principles of autonomy and flexibility. But because the CPV program is designed to spur economic revitalization in specific areas, visa holders should be required to live within the applying county or locale with which they were paired, and they should find employment within the relevant CZ. If the visa holder is unable to find suitable employment, they should be permitted to petition for relocation to a different CPV-eligible community, during which time their visa would remain valid.

Visa Duration and Family Eligibility

CPVs should last for at least five years, long enough for the recipient to immerse themselves in their community. At the end of the initial five-year period, the visa holder should be able to renew their visa for five more years, for a total maximum duration of ten years. At the expiration of the second visa, the visa holder should be eligible to apply for permanent residency under a newly created post-CPV green card category. Receipt of a CPV would not preclude the recipient from obtaining permanent residency earlier through another stream, such as employer sponsorship or marriage.

After an individual arrives on a CPV, they should be eligible to apply for their spouse and any minor children living abroad to receive visas. The spouse could be eligible to work as well.

Program Size

The program should be sufficiently large to have the intended effect of helping to economically revitalize host communities but not so large that it eclipses other streams of immigration in existing law. The precise number of visas should be determined by USCIS, though comparable programs such as H-1B or H-2B visas (65,000 and 66,000 per fiscal year, respectively) offer useful points of comparison.