Increase Completion and Reduce Inequities

Introduction

After several decades of determined investment and coordination, a college education is now available to a substantial majority of Americans. Nearly 90 percent of all high school graduates enroll in college classes during their early adulthood. However, a much smaller percentage of Americans—an unacceptably small percentage—actually complete the education they start. By one measure, about 60 percent of students who pursue a bachelor’s degree complete one. And about 30 percent who pursue a certificate or associate’s degree earn the credentials they seek.

A wide variety of challenges conspire to prevent students from graduating. The path to completion is especially difficult for students who do not have a strong academic experience in high school; for older students returning to college after many years or enrolling for the first time while balancing family and work responsibilities; and for students who are the first in their families to attend college. These challenges are compounded for students who come from low-income families and struggle to meet day-to-day financial burdens. And completion rates, when analyzed by gender, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, reveal substantial inequalities. Women complete at higher rates than men, White and Asian students complete at higher rates than Black and Hispanic students, and high-income students complete at a higher rate than their low-income peers. These disparities represent a significant challenge to an education system that has long prioritized the expansion of access over other considerations.

Evidence shows that the greatest benefits of an undergraduate education derive from earning a credential and not simply from attendance. Students who do not graduate are often wasting their scarce resources of money and time. Taxpayer-funded subsidies and scholarships are not being fully realized. Most important, the nation is squandering the enormous potential of its students if it does not ensure that they can graduate within a reasonable period of time.

This section of the report begins with a discussion of the most significant factors associated with low college completion rates. It then turns to promising ways in which colleges and universities themselves can reengineer their operations and processes to spur increased completion rates. The section concludes with an analysis of the interconnections among colleges and universities as well as with other entities and how such networks must be strengthened if completion rates are to be improved significantly.

Where the Pathways to Completion Break Down

For too many college students, no clear path leads to the finish line of a timely graduation. Many take required developmental courses that do not count toward graduation; many take time off or switch between full-time and part-time study; and many must juggle families, jobs, and schoolwork. The cumulative effect of these interruptions and challenges is that more students take more time, and often earn more credits, than they need to graduate—and many do not graduate at all.

Academic Preparation: Many recent high school graduates as well as adults arrive at college academically underprepared. One-half of all college students are required to take developmental (remedial) courses that reteach high school–level reading, writing, and math. Many students do not complete these required courses and thus do not complete a college credential.

For example, only 28 percent of community college students who take a developmental course earn a degree within eight years, compared to 43 percent of students who did not require developmental education.43 Another analysis found that students pursuing a bachelor’s degree who take a developmental course are 74 percent more likely to drop out of college than their nondevelopmental course–taking peers.44 Developmental education is discussed more fully later in this section, reporting that a growing body of research critiquing its practices points the way toward important reforms.

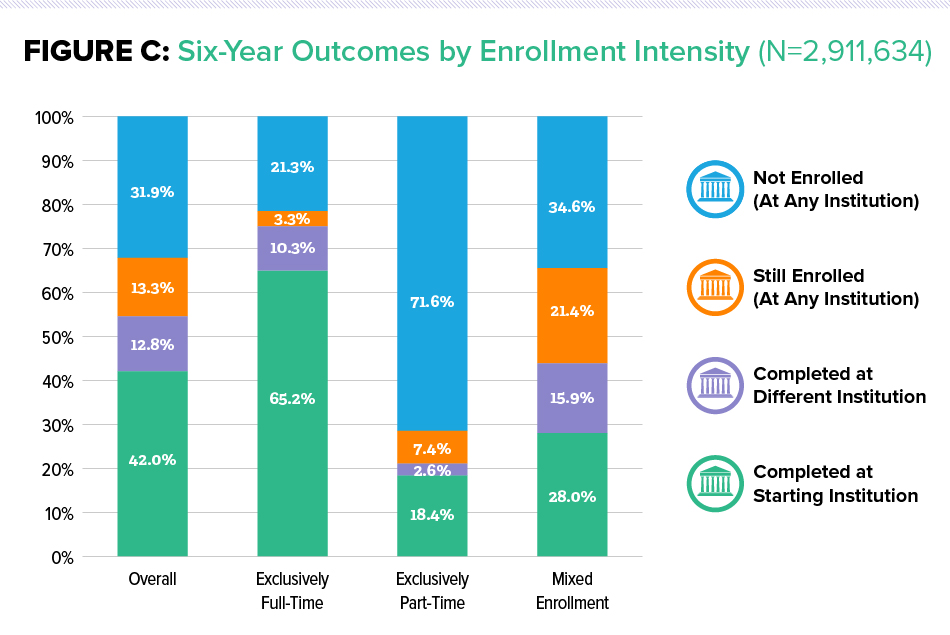

Enrollment Status: The difference in completion rates between students who enroll full-time versus part-time is striking. Figure C looks at the outcomes enrollment status in 2015 of almost 3 million students who started college in the fall of 2010. Less than one-quarter (21.3 percent) of full-time students dropped out in this six-year time frame, compared to almost three-quarters (71.6 percent) of part-time students.

SOURCE: D. Shapiro, A. Dundar, P. K. Wakhungu, X. Yuan, A. Nathan, and Y. Hwang, Completing College: A National View of Student Attainment Rates—Fall 2010 Cohort (Signature Report No. 12) (Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, December 2016), 16, Figure 5.

Institutional Choice: Some colleges and universities systematically and routinely outperform their peers when it comes to completion rates. A study that examined approximately 1,300 colleges and universities from 2003 to 2013, for example, found that although overall completion rates improved over this time period, they did not improve uniformly. Some institutions made huge gains, while others stayed flat or even lost ground. And in some cases, although an institution’s graduation rates improved, they did not improve for all student groups.45 Some colleges do better than others when it comes to completion, and within each institution some programs and majors do better than others.

Many underrepresented students, both recent high school students and adults, are often steered into colleges and/or academic programs with very low completion rates—and their future opportunities are limited as a result. This phenomenon, known as “undermatching,” mainly occurs at the front end of the application process, not in college or university admissions offices, because students do not know where they have the best chance to earn a college credential and many believe they will not be able to afford tuition at more competitive four-year colleges. However, research shows that students who are identical on measures such as high school GPA and SAT/ACT scores do better when they go to schools with higher graduation rates.46 Students from all backgrounds should attend the most challenging colleges they can.

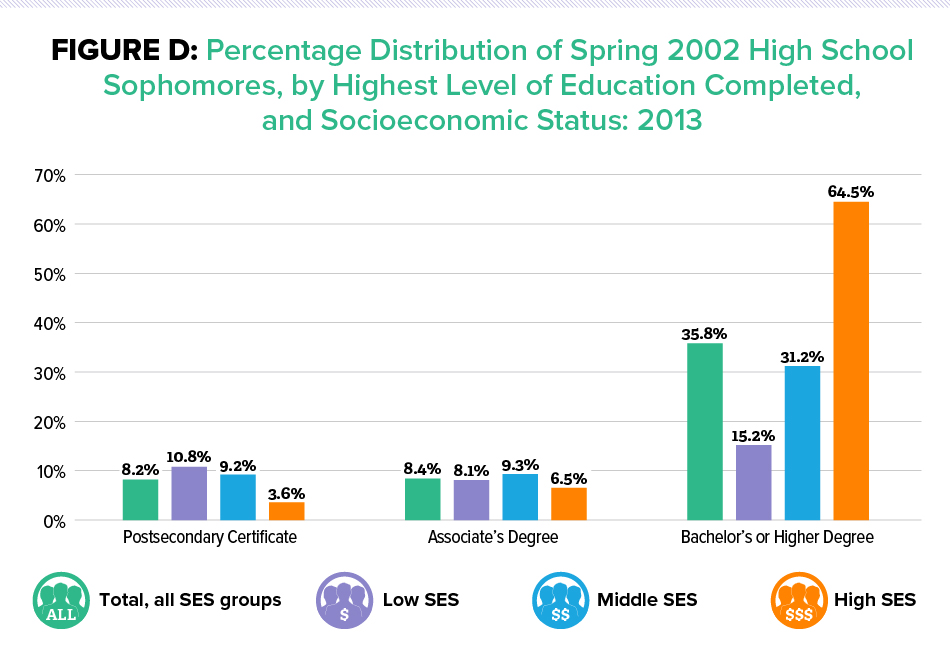

Demographics—Socioeconomic Status: Figure D compares, by socioeconomic status, the highest level of education achieved as of 2013 by students who were high school sophomores in 2002. A higher percentage of students from the lowest socioeconomic status (SES) group earned certificates and associate’s degrees compared to the highest SES group. This relationship is starkly reversed when it comes to bachelor’s degrees: only 15.2 percent in the low SES group earned a bachelor’s, compared to 64.5 percent of their high SES peers.

SOURCE: Percentage Distribution of Spring 2002 High School Sophomores, by Highest Level of Education Completed, and Socioeconomic Status: 2013

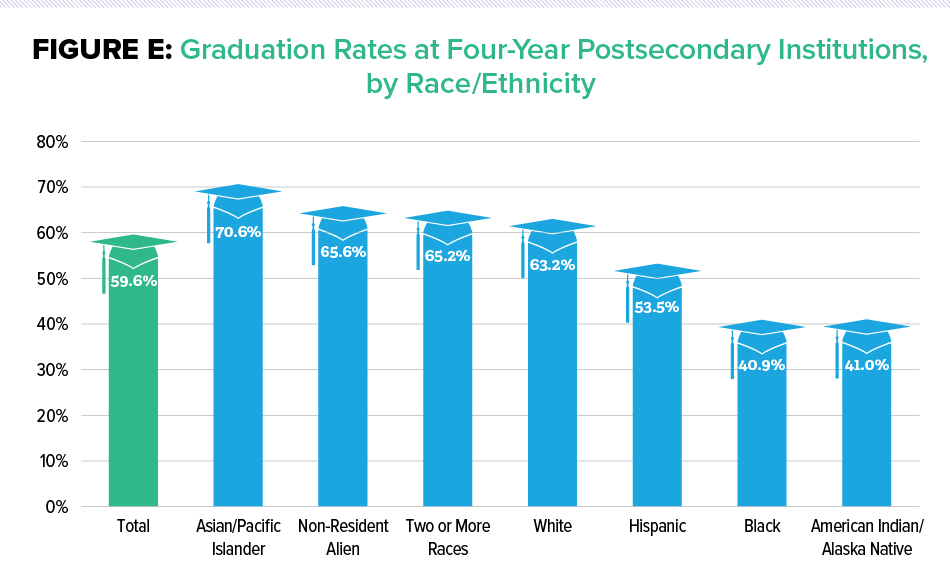

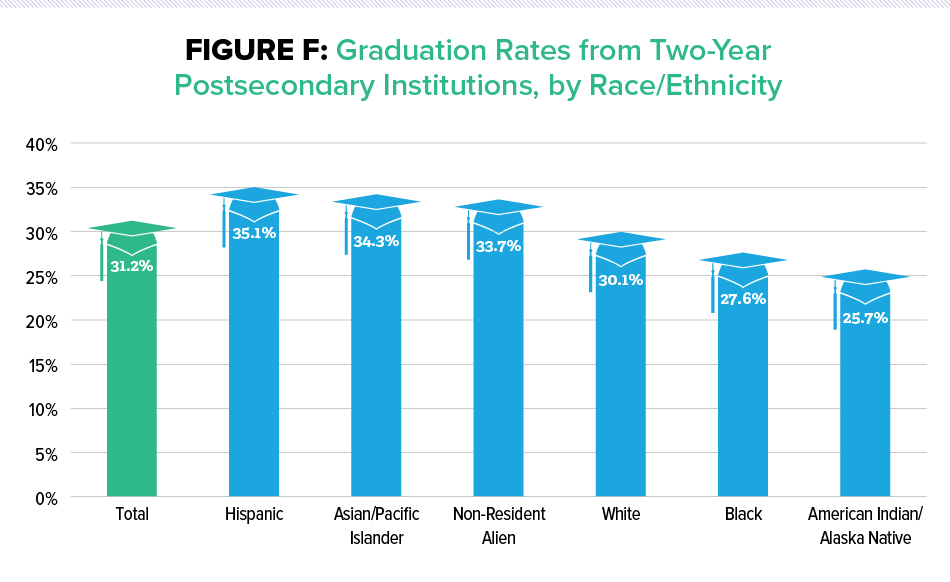

Demographics—Race/Ethnicity: As shown in Figures E and F, White and Asian students at four-year institutions graduate at higher rates than Black and Hispanic students. At two-year institutions, this trend is somewhat different, with Asian and Hispanic students completing at slightly higher rates than White and Black students.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, 2016 Digest of Education Statistics, Table 326.10.

Note: Six-year graduation rate from first institution attended for first-time, full-time bachelor’s degree–seeking students at four-year postsecondary institutions, by race/ethnicity: 2008 starting cohort. NCES defines “non-resident alien” as “a person who is not a citizen or national of the United States and who is in this country on a visa or temporary basis and does not have the right to remain indefinitely.”

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, 2016 Digest of Education Statistics, Table 326.20

Note: Graduation rate from first institution attended within 150 percent of normal time for first-time, full-time degree/certificate-seeking students at two-year postsecondary institutions, by race/ethnicity: 2006 starting cohort. NCES defines “non-resident alien” as “a person who is not a citizen or national of the United States and who is in this country on a visa or temporary basis and does not have the right to remain indefinitely.”

Demographics—Gender: Women are completing college at higher rates than men. Among first-time, full-time students who enrolled at a four-year institution in 2008, 62 percent of women and 57 percent of men graduated within six years.47 Similar patterns held for first-time, full-time students who pursue an associate’s degree or certificate at a two-year college. For those who first enrolled in 2008, 34 percent of women completed, compared to 27 percent of men.48

In addition to the factors discussed here, a host of other considerations serve to jeopardize students’ college careers. Being a single parent, working more than 30 hours per week, and being a first-generation college student—all these are associated with lower completion rates. Educational aspirations, motivation, and family support also play crucial roles in determining college success. Taken together, these characteristics underscore the complex and challenging ways that precollege experiences, college choices, demographics, and individual circumstances influence college completion rates. There are no silver bullets or simple formulas to address these issues, but rather they must be approached with equally complex and deliberate responses.

Limitations and Complexities in Measuring Completion Rates

The national Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) is the primary data source on colleges and universities in the United States. IPEDS provides publicly available data on all institutions that participate in federal student financial aid programs and is managed by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Due to their availability, many of the completion rates cited in this report refer to first-time, full-time students who complete their degrees within 150 percent of normal time (e.g., six years for a “four-year” bachelor’s degree and three years for a “two-year” associate’s degree). However, these measures exclude part-time and transfer students and thus undercount graduation rates. NCES recently implemented a new supplementary measurement to include part-time and “non-first-time” (transfer) students in their data collection efforts. These outcomes measures will track whether students received a credential within six years, within eight years, are still enrolled at their initial institution, are enrolled at another institution, or have an unknown enrollment status. This should provide a more holistic and realistic picture of how the full range of students are progressing toward completion over time. Several voluntary data collection initiatives also seek to provide a more comprehensive, nuanced understanding of college student completion rates, including the Voluntary Framework of Accountability, Complete College America, and Student Achievement Measure. Additionally, many states have the ability to track and analyze student progression through their statewide longitudinal data systems, and there are early efforts to coordinate the tracking of college student progress across state lines. It is critical that comprehensive measures that track student progression into, through, and beyond their college experiences serve to identify the weaknesses in college completion and focus on solutions where they are most needed. The further development and linking of the indicators that measure student progression must continue.

Fully Tapping Reservoirs of Human Potential

Over the next few decades, demographic changes will result in a declining number of Americans in their late teens and early twenties, the cohort of traditional college students. As a result, the number of high school graduates entering college over the next decade is expected to remain flat at about 3.3 million annually, implying level college enrollment rates nationally (the southern and southwestern regions of the country will see gains, while other regions may well experience enrollment declines). At the same time, the country will experience a decline in the working-age population of 18- to 65-year-olds. With fewer young people in the professional pipeline and fewer working-age adults overall, the only way to keep pace with or exceed current rates of economic growth will be to increase the productivity of the American workforce. In some industries in particular, automation may help fill the gaps. But, overall, the best strategy for addressing these demographic trends is to empower individuals to lead more productive lives, at home and at work. College completion has proven to be a particularly effective way to achieve this goal.

One way of achieving the nation’s growth objectives is to improve college access and completion rates—and of course the quality and relevance of education—of all student populations. Inevitably, institutions will continue to focus more and more on recruiting and serving larger numbers of students from populations that are currently underserved, especially the country’s growing Hispanic population, the large pool of working adults, students from low-income families in rural areas, and those who are incarcerated:

- Hispanics are the fastest-growing minority group in the country—the number of Hispanic high school graduates is projected to increase by 50 percent by 2032—yet they have the lowest educational attainment levels. This implies a significant opportunity for increased college-going and completion in this population.

- About one-fifth of Americans 25 and older have some college experience but no degree.49 These adult students range from veterans returning from service to displaced workers seeking to change careers to working parents wanting to improve their job prospects. Common barriers for adults seeking to complete a college credential include the associated costs and the challenge of balancing work, family, and community responsibilities. For these reasons and more, “reentry adults” often end up trying repeatedly without success to complete a degree or certificate. Among students who drop out for at least a year and then return to college, only about one-third complete a credential compared to over half of first-time students.50

- Despite the fact that high school students from rural areas have strong high school graduation rates (85 percent), only 29 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds in rural areas are enrolled in college, compared with 48 percent of their urban peers.51 Moreover, the rural-urban gap in college attainment is growing. From 2000 to 2015, the share of urban adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher grew from 26 percent to 33 percent; for rural areas, the share grew from 15 percent to 19 percent.52

- Incarceration rates in this country are alarming: between 1972 and 2010, the number of people in U.S. state and federal prisons rose 700 percent,53 with young Hispanic and Black men with very low levels of education disproportionately represented. Although the number of adults in the U.S. correctional system has declined slightly in the past few years, Blacks and Hispanics are incarcerated at much higher rates than Whites. For example, in 2015, imprisonment rates for males ages 30 to 34 were 5,948 per 100,000 Black males, 2,365 per 100,000 Hispanic males, and 1,101 per 100,000 White males.54 These trends have profound implications for the educational and economic opportunities for these individuals and their families and for the country as a whole.

These and other challenges should be met and turned into opportunities—the infusion of new ideas and energy for undergraduate education and for a nation that has always benefited from the interactions and innovations nurtured at its colleges and universities. We discuss below what we see as promising opportunities to build more success as we consider our nation’s future.

Institutional Reengineering

One potential hazard in the current push to improve college completion rates is the risk that colleges and universities might pursue strategies that improve completion rates at the expense of access or quality. The Commission strongly urges institutions to adopt the more challenging and ultimately rewarding path that addresses completion, access, and quality simultaneously.

The Commission recognizes a basic if implicit compact between student and college: At the moment of enrollment, students dedicate themselves and their energies to succeed in their studies, and institutions promise to provide the structure and supports necessary for the attainment of a meaningful degree. Educators and policy-makers often grapple with the question of how students can change and be better prepared to succeed in college. An equally important question that must be faced is, “How can colleges and universities be better prepared for their students?”

The Commission recognizes that many colleges and universities around the country are taking important steps to improve completion rates and reduce gaps across student populations, even as they maintain a strong commitment to access and high academic standards. A growing body of research and practice emphasizes the importance of structure and support for students, early entry into well-defined programs that have clear and transparent maps to completion, and the active use of student-level data to measure and improve student progression.55 The most successful institutions employ a set of integrated strategies, increasingly known as “guided pathways,” beginning with the proactive use of student data to understand progression and attrition; incorporating better teaching and learning; utilizing sophisticated predictive analytics; and enhancing “intrusive” advising, career counseling, and financial aid support. Some institutions have also taken the step to significantly narrow students’ choices. Rather than confront students with a bewildering array of courses, majors, and enrollment options in a typical college catalog, some schools offer a limited number of structured pathways, with curricula and course schedules designed to make these paths easier to negotiate.

PROMISING PRACTICE

Florida State University

Florida State University (FSU), a 32,000-student public research institution, has been engaged in determined efforts to increase retention and graduation for years, and the work has paid off. For the student cohort that entered FSU in 2008, the six-year graduation rate was 79 percent, a 16-percentage-point improvement from 1988 outcomes and in the top third of large research universities. FSU committed to a university-wide effort to support students more effectively, particularly those from underperforming subgroups, by using data to identify the biggest problems and to create institution-wide structures for ongoing discussion, so that solutions would be grounded and would have faculty and staff support. FSU pioneered implementation of detailed program mapping so that students understand what they need to do to complete program requirements. Reinforcing the mapping is an investment in advising so that students get help before they fall off track. FSU’s program mapping and proactive advising approach have become key components of promising initiatives across two- and four-year colleges and universities.56 Its model is being adapted by the other ten members of the University Innovation Alliance, a consortium of large public research universities established to test, scale, and diffuse relatively low-cost completion initiatives developed by their peers.

This transparency and greater structure facilitates college planning and has proven to be especially helpful to first-generation students and others who lack familiarity with how colleges operate. It motivates students to complete their courses in a timely way and often provides greater clarity about how certain pathways may affect a student’s future employment prospects. Greater clarity also serves to motivate students to complete their courses in a timely way. On a case-by-case basis, such approaches have proven to be very successful. They must now become widespread in practice at colleges and universities around the nation. It should no longer be acceptable to defend existing practices with the bromide, “that’s the way we’ve always done it here.”

While each campus must find its own way to understand and address student completion in an integrated and comprehensive manner, the following sections highlight some of the most important components in need of continued attention and experimentation: remedial education, program structure and pace, student support, and the potential of emerging technologies.

PROMISING PRACTICE

City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs

The City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP), designed to help more associate’s degree–seeking students graduate and complete more quickly, has demonstrated solid results in research studies and is poised to expand from 4,000 to 25,000 students by 2018. ASAP was created to overcome three common obstacles to completion: financial burdens; inadequate advising and support; and academic underpreparedness. Through a tightly structured program, ongoing and intrusive advising, meeting students’ full financial needs, and other supports such as free transit passes, ASAP serves students who are predominantly low income (75 percent receive Pell grants) and are either college-ready or require one or two developmental courses. Students are expected to attend full-time and graduate within three years. A random assignment evaluation found that ASAP students outperformed control group students on persistence, credit accumulation, full-time enrollment, three-year graduation, and transfer to four-year colleges. The three-year graduation rate was nearly double that of the control group (40 percent versus 18 percent). After three years, 25 percent of ASAP students were enrolled in a four-year school (versus 17 percent of the control group).57 Although the costs associated with ASAP students are greater compared to students in traditional programs because of the extra services, the overall cost for each graduate is less for students in ASAP because of the considerably higher graduation rates.58

Developmental (Remedial) Education

“College readiness” is a complex concept measured in multiple and controversial ways, including standardized test scores and transcript analysis. All too often, the determination that someone is “ready for college” is predicated on a superficial set of characteristics: “acting and looking like the students who have always succeeded at this college.” Such determination can be shortsighted. Standards of college readiness should be based on real evidence of factors that connect to college learning. Failure to abide by the evidence in such cases can be costly, for individual students and for the nation as a whole. In practice, students who do not meet the readiness standard, however defined, are typically required to enroll in developmental courses, which do not count toward a college credential, before they can take college-level courses. They require additional time and tuition, further delaying completion. As noted earlier in this section, one half of all college students take developmental courses, and degree completion rates are low for these students; indeed, many do not even complete their developmental courses.

Placement into developmental education is often determined by a brief high-stakes standardized exam, but recent research suggests such exams on their own do not reliably place students into the appropriate level of course-taking. As a result, some institutions and states are adopting different approaches to making this important determination. Long Beach Community College changed its placement policy for recent high school graduates to include students’ high school GPA, a policy shift that enabled the school to increase placement into college-level English from 14 to 60 percent and college-level math from 9 to 30 percent—without any statistically significant difference in pass rates in those courses between those who were placed under the new policy and those placed under the test-only policy. Connecticut passed legislation in 2012 requiring its public colleges and universities to revamp how students were placed into developmental education and to limit the time in developmental courses to one semester.

PROMISING PRACTICE

The California State University System

The California State University System (CSU), made up of 23 campuses serving almost 500,000 students annually, is working to increase its six-year graduation rates from its current 57 percent rate to 70 percent by 2025. If the system succeeds, it will have come a long way from its 46 percent completion rate in 2009. CSU is also focusing on increasing the four-year graduation rates for transfer students from 73 percent to 85 percent. Through a combination of campus efforts and system-wide coordinated actions such as hiring more tenure-track faculty and academic advisors, improving curricular alignment with K-12, supporting faculty innovation and course redesign efforts, and strengthening relationships with community and business partners, the system hopes to produce 100,000 additional graduates by 2025 as a result of this initiative.59

Once students are placed properly in standard and/or developmental courses, efforts to reform developmental education are key to improving college completion rates. The Commission supports the recent institutional, research, and policy initiatives that are restructuring the content and delivery of developmental education, aligning content to the skills needed for success in a student’s chosen program of study, and adopting accelerated methods like “corequisite” developmental instruction linked to first college-level math and English courses. The Community College of Baltimore County’s Accelerated Learning Program placed developmental English students into college-level English classes while enrolling them at the same time in a supplemental course in which the same faculty member provided additional instruction. Students in this corequisite model were more likely to pass their first two college-level English courses than students who took a traditional developmental course. In addition to corequisite models, some colleges have compressed their developmental sequence into fewer semesters, moving through the same material at a faster pace. New Mathways, developed by the Dana Center at the University of Texas-Austin, and the Statway and Quantway courses developed by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching integrate developmental and first-year college math into seamless year-long courses that show great promise.

PROMISING PRACTICE

The University of Maryland University College

The University of Maryland University College (UMUC) was created specifically to serve the adult learner population. As such, the university’s strategies—including a strong focus on online course delivery, emphasis on workforce development, and use of data for student support, program design, and institutional decision-making—take into consideration the unique circumstances and barriers that adult learners face. Of the approximately 84,000 students who are enrolled at UMUC, 87 percent took at least one online course in 2015. The institution’s approach to online education is not only notable for its scale: A part of UMUC’s online model involves a centralized and accessible support system and online community spaces where students and faculty engage with one another and share resources. Reflecting the institution’s commitment to giving students the opportunity to learn from professionals in their field, 90 percent of UMUC’s faculty are part-time and work on a contract basis. This “scholar-practitioner” faculty model plays a large role in the institution’s focus on workforce development, and students report high levels of satisfaction as a result. A survey of 2013 bachelor’s degree recipients found that 63 percent of students were satisfied with job preparation. That number rose to 85 percent when asked about preparation for continuing graduate or professional studies. Using data to drive decision-making at all levels is another aspect of UMUC’s success in serving adult students. Conducting analyses on why some students drop out, for example, has informed policy changes that directly affect outcomes for students.60

Program Structure and Time-to-Degree

Despite the fact that credentials are typically described in terms of “two-year” and “four-year” degrees, most students take longer to complete associate’s and bachelor’s degrees than those terms imply. For example, students across the country who started at a “four-year” college took an average of five years and ten months to earn a bachelor’s degree.61 In California, half the state’s community college students take four years or longer to complete a “two-year” degree.62 For some students, slow progress may be necessary, but a growing body of evidence on predictors of completion suggests that most students—especially students who attend less-selective institutions or come from low-income families—would benefit from a shorter time-to-degree and that reducing the time will likely increase graduation rates.63 Early research indicates that by limiting the vast array of program and course choices students have before them, and by providing more guidance and mentoring, institutions are able to help students conserve precious time and accelerate progress to a degree.

Efforts to reduce time-to-degree tend to focus on several related challenges. One is the tendency of many “full-time” students in two- and four-year programs to take only 12 credit hours a semester, even though on-time completion requires 15 credits each semester. Some states, such as Hawaii, Colorado, and Utah, utilize marketing campaigns and incentives encouraging students to take a 15-credit load. In Indiana, state financial aid is tied to a requirement that students take 30 credits a year. This policy has led to a 5.2 percent average increase in the likelihood of students earning 30 credits or more a year—without a significant decline in completion or fall-to-fall retention rates.64 States, systems, and institutions are testing other incentives to speed up time-to-completion. Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis discounts the cost of summer credits 25 percent for in-state students. Temple University’s Fly in 4 Campaign pays students up to $2,000 if they agree to work no more than 15 hours a week and commit to following the university’s directions on how they can complete in four years.

Perhaps the most promising strategies to reduce time-to-degree are those that streamline requirements and course sequences. In the late 1990s, Florida State University tried to reduce the large number of students who graduated with more than 120 credits by creating program maps that made it more transparent to students which courses and in what sequences they needed to pursue to graduate in a timely way. Initially, this change had no impact on time-to-degree, though it did result in slightly improved graduation rates. When the university turned the program maps into the default pathway for students and required undecided students to enter an exploratory major in their first semester, the four-year graduation rate increased by 17 percentage points. From 2000 to 2009, the share of students who had more than 120 credits when they graduated dropped precipitously from 30 to 5 percent.65

Student Engagement and Support

Whether they attend two- or four-year institutions, and whether they enroll full- or part-time, college students’ educational experiences are far broader than their academic courses and experiential learning activities. One of the primary benefits of the college experience, for example, is participating in the range of activities and services available to students in the hours they are not in class or studying. Research over several decades concludes that the more actively students engage with their peers, with faculty and staff, and with their academic program, the more likely they are to progress, persist, and complete. Both the National Survey of Student Engagement at four-year institutions and the Community College Survey of Student Engagement have found a similar correlation between engagement and success, even for community college students, who do live away from campus, work more hours than their four-year counterparts, and often attend on a part-time basis.66 A recent review of research studies indicates that faculty participation in professional development activities and use of evidence-based teaching practices have a positive relationship with student persistence and degree completion.67 It is important to continue to understand more fully the connection between teaching strategies and student completion rates.

However, many students, particularly those from low-income and first-generation college families, are unable to participate in campus life in a meaningful way, and many face significant nonacademic obstacles to success. Financial reversals, housing challenges, car breakdowns, bus route changes, an illness or death in the family, childcare difficulties—each can be sufficiently disruptive for students with complicated schedules and little flexibility in their lives. One helpful strategy is for college administrators to have discretionary funds at their disposal to help students immediately address these difficult temporary financial circumstances.68 Another approach is to more purposefully use federal work-study experiences to better prepare students for postcollege employment.69

In addition to these obvious obstacles, many students face subtler barriers to academic success rooted not in their academic ability but in a lack of the knowledge, support networks, and confidence that can be so helpful to anyone trying to navigate the college experience. To help address all of these challenges, many colleges and universities make available a range of nonacademic student supports outside the classroom to help improve academic performance. The Community College Research Center identified four mechanisms by which nonacademic support services appear to promote student success:70

- Creating social relationships with peers and instructors;

- Clarifying aspirations and enhancing commitment to specific career goals and path;

- Developing college know-how in order to manage the logistical, behavioral, and cultural demands of college; and

- Making college life feasible by minimizing financial and other daily life obstacles.

Enhanced advising, student success courses, and learning communities have demonstrated modest results in improving academic performance and persistence in college. Yet short-term and modest interventions tend to have short-lived results, so reformers have begun to design and implement interventions that are more intensive and systematic and provide long-term access to academic, financial, and social supports.

Technologies Supporting Student Completion

New technologies to support the student experience are evolving in different directions. Many have significant potential to help more students complete degrees. Advances in adaptive learning technologies are beginning to become available, creating on-demand, automated tutoring that can support students in customized, efficient ways. Learning analytics are being incorporated into more comprehensive systems that combine education program planning, progress tracking, advising and counseling, and early alert systems that initiate proactive interventions. The growing use of free Open Educational Resources is reshaping the textbook market and allowing students greater access to high-quality educational materials at much lower costs. The combined use of data systems and close monitoring have already proven their worth in improving completion rates.

However, it is still early in the evolution of educational technology—for advising as for instruction. Even as the pace of technology innovation accelerates, there is still insufficient evidence to determine the extent to which new classroom technologies can address the most fundamental challenges undergraduate education will face over the next decades, and strong results for at-risk students have proved elusive. Thorough research on promising practices will be critical as the country seeks to address a host of challenges.

Systems Approaches

Student Transfer

Each college and university has the responsibility to critically evaluate its internal approaches and make the changes needed to ensure that the students who arrive are able to complete their studies in a timely way. Ideally—because it’s the least complicated option—a student would start and finish at the same college. However, the more complicated reality is that a significant proportion of undergraduate students—approximately one-third—transfer from one institution to another or enroll in two institutions at the same time during their college careers. And among all students who completed a degree at a four-year college in 2015–2016, almost half (49 percent) had enrolled at a two-year college in the previous ten years.71 Beyond the “vertical” movement from a community college to a four-year college or university, transfer is also “lateral” (e.g., community college to community college or four-year to four-year); “reverse” (e.g., state college to community college); and “swirling” (multiple institutions). Further complicating student transfer is the growing array of ways students earn college credit: through high school dual enrollment, early college, and vocational programs; competency-based programs; prior learning assessments; nationally recognized exams (e.g., CLEP, DANTES, UEXCEL, Advanced Placement Examinations); and prior military education.

The transfer of academic credit from one institution to another is often a messy, perplexing, and frustrating part of the college experience for faculty, staff, and, most important, for the students themselves. This reality demands that an institution look not only inwardly but externally to improve relationships with other colleges and universities in order to increase student success. There is much work to be done in this regard. Confusing and contradictory policies and agreements, the rejection of course credits for unclear reasons, the inability to apply some completed courses to some credentials, and inconsistent student access to information and appeals processes have complicated student transfer for decades. Students who transfer frequently lose credits, repeat courses, extend their time-to-degree, and, in many cases, fail to complete their degrees. Only 14 percent of students starting in community colleges transfer to four-year schools and earn a bachelor’s degree.72

The failure to address transfer obstacles ultimately wastes the precious time, money, and energies of students and disproportionately affects those most at risk: students who are first-generation, working adults, low-income, and/or from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. It is critical for institutions to work collaboratively, informed by trust and transparency to systematically align courses and academic programs; to make transfer credit decisions based on data rather than impressions; and to provide systematic and coherent advising and support to students.73 A strong cultural shift in the undergraduate education landscape toward openness and willingness to evaluate, recognize, and apply the college-level learning that takes place at multiple institutions through various mechanisms will do more to advance the educational opportunities for underrepresented students than any other national policy, including affirmative action.

The University of Central Florida (UCF) offers guaranteed admission to graduates of Valencia College and three other community colleges through its DirectConnect program. Students from those schools have access to reliable information, UCF advisors, and can take third- and fourth-year UCF classes on Valencia’s campus, saving students a two-and-a-half-hour bus ride. DirectConnect graduates from the community colleges are guaranteed UCF admission and they have been graduating at a slightly higher rate than native UCF students.74 The Mandel Continuing Scholars Program is a partnership with Cleveland State University (CSU), Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C), and the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation in Ohio to increase the number of Tri-C students who transfer into the Mandel Honors College at CSU. The program identifies community college students through receptions, individual or group meetings, and recommendations to engage with faculty and students in the bachelor’s degree program they aspire to enter. Through a coordinated combination of scholarship support, stipends for books and transportation, and academic and career advising and mentoring, the program goes beyond just ensuring that academic credits transfer to helping create a welcoming environment and sense of belonging for community college students by building social networks and providing ongoing support through bachelor’s degree completion.

Many states are working toward coordinated processes to help students transfer more efficiently to the baccalaureate programs of their choice. In Massachusetts, faculty from across two-year and four-year public colleges and universities identified the foundational courses for 20 majors, created pathway maps of courses that make up the first 60 credits, and engaged in dialogue to identify competencies and skills that students need to master in the first two years.75 In the western part of the country, seven states are participating in the Interstate Passport, a new program that focuses on the transfer of lower-division general education courses.76

Collaborations with Alternative Educational Providers

Growing numbers and types of providers that are not colleges or universities offer pieces of educational experiences comparable to college-level learning. Career and technical schools, corporate training programs, MOOCs, coding boot camps, and industry groups, to name a few, may play an increasingly important role working with colleges and universities. If indeed these kinds of opportunities multiply (they are a growing sector but remain a small segment of the undergraduate landscape), this diversification of options has the potential to expand college-level learning but could also become a daunting maze that students must navigate in deciding on their best path forward.

New efforts to help build educational crosswalks and consider innovative ways to represent learning are taking hold. These include the emergence of microcredentials, digital badges, and certifications. The Commission supports efforts to improve pathways across educational routes and to measure and afford recognition to college-level learning that takes place outside the bounds of traditional and familiar college offerings. Regardless of the provider, students pursuing a college-level certificate, associate’s degree, or baccalaureate program should expect to gain the knowledge, skills, and experiences to improve their near-term economic prospects as well as the ability to more skillfully navigate their personal and public worlds and participate fully in a democratic society.

PROMISING PRACTICE

The Partnership between Northrop Grumman and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Northrop Grumman (NGC), a leading global security company, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) have had a robust partnership for more than 20 years that strengthens both organizations and also strengthens the region.

- Early in this partnership, the two organizations codeveloped a master’s program in system engineering. To date, more than 500 NGC employees have earned this advanced degree.

- With support from the Northrop Grumman Foundation, UMBC established its successful Cyber Scholars program, focused on attracting more women and minorities to the cybersecurity field. UMBC, NGC, and the Northrop Grumman Foundation are making an impact in local communities through an innovative multiyear partnership in Baltimore City Schools designed to boost STEM resources and student outcomes.

- Together UMBC and NGC launched a novel cybersecurity business incubator program (CYNC) run by bwtech@UMBC, UMBC’s research and technology park.

- NGC executives serve on advisory boards at all levels of the university, and the company’s scientists and engineers are on campus regularly to speak with and mentor students inside and outside the classroom.

- Finally, NGC is a top recruiter of UMBC talent at the undergraduate and graduate levels, with large numbers of UMBC students securing internship opportunities every year.

Collaborations with Business and Industry

New substantive and mutually beneficial partnerships between businesses and colleges help students gain the knowledge and skills needed for the workforce and help employers secure well-prepared employees. These relationships vary with the type of college, region, and industry, but in an increasingly interconnected world the walls between colleges and employers need to be broken down, and bridges must be built that help meet the needs of students and future employees. Given the differences in mission and culture often found between colleges and companies, organizations seeking to work together effectively should adopt mindsets that seek to understand each other’s needs and be open to constructive criticism. Creating trust and transparency is vital for building an ecosystem that comprises different institutional types. Affiliations range from simple agreements such as employers offering internship placements and mentoring for students to multilevel partnerships sustained and enhanced over years and involving input from industry on curriculum development and evaluation, research and experiential opportunities for faculty, and placement support for students.

PROMISING PRACTICE

P-TECH

The P-TECH model, launched by IBM, is a Grades 9–14 school whose graduates earn an industry-recognized associate’s degree, have benefited from business mentors and work experience, and are prepared to enter a high-demand industry. Begun in 2011 in a single school in Brooklyn, the model is now being implemented in 70 schools across the United States, Australia, and Morocco. The State University of New York system, for example, embedded this program throughout all of its 30 community colleges. Variants on this model can be found in Texas and other states that have encouraged career-focused early college high schools and close partnerships between local industry, high schools, and community colleges, resulting in momentum for both college (through dual enrollment) and career (through work experience and mentors). These partnerships also serve to incentivize students to learn and to stay in school by giving them added confidence that the academic work they are doing will prepare them for actual jobs when they graduate as many students see no clear link between what they learn and productive employment afterward.

The most comprehensive partnerships are regional, involving colleges and universities, K-12 institutions, employers, workforce/economic development agencies, labor groups, and social service providers, and connect the supply and demand sides of the local labor market through new credential programs, information-sharing venues, and opportunities for learning and sharing across business and higher education. In many communities, these “career pathways” efforts begin in the high schools, particularly in areas with strong career and technical education programs. Taking their inspiration from European apprenticeship programs that serve a majority of youth in countries like Switzerland and Germany, these efforts are creating new and promising ways for educators and employers to understand each other better and for alternative routes to high-demand employment to develop that expand young people’s postsecondary college and career choices.

State and Federal Roles in Accelerating Completion Goals

State governments have a special role in ensuring that their public agenda for higher education includes a focus on improving college completion rates. While state investment in public higher education has declined over time, states still remain a major funder and oversee a range of academic and fiscal policies that influence and directly regulate institutional behaviors. Government leadership can and should enact comprehensive and coordinated strategies to make college completion a top state priority. State leaders should determine their state’s educational attainment goals, communicate and promote these goals to their citizenry, and collaborate with campuses, government agencies, business and industry, and community-based organizations. States can help set campus goals for increasing college completion rates, support campuses through targeted institutional allocations and student financial aid, and track improvement by population subgroup, utilizing state longitudinal data systems. States can use discretionary funds to create competitive grants that encourage evidence-based approaches to improving completion, including promoting informed program choices, limiting excess credits, reducing developmental coursework, and redesigning curricula.

The following section of the report will focus on changes that can and should be made at the federal level to promote college affordability, a key element in increasing college completion rates. In addition to these actions, the federal government should revisit the 2008 amendment to the Higher Education Act that banned a federal student unit record data system and resume efforts to build a system that can track institutional, state, and national trends related to student progress and outcomes. A great deal of student level data is currently collected by the U.S. Department of Education’s National Student Loan Data System, the Internal Revenue Service, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Removing student-identifying information and connecting this data would provide invaluable information in helping identify and address a range of concerns.

Tennessee has made undergraduate education access and success a top priority over the past 15 years, under two governors from different political parties. During Democratic Governor Philip Bredesen’s two terms, which ended in 2011, Tennessee’s legislature passed the Complete College Tennessee Act, which took steps to increase and simplify transfer from two- to four-year institutions, reduce remediation at four-year schools, create a statewide community college system, and introduce a new performance-based funding formula. The initiative also included a focus on K-12 improvement. When Republican Bill Haslam assumed the governorship in 2012, he continued the state’s emphasis on education, committing Tennessee to a goal that 55 percent of the state’s adults would have a postsecondary degree or credential by 2025 (up from 33 percent). The state introduced, among other initiatives, the Tennessee Promise, a last dollar scholarship for high school graduates that guarantees full-time freshmen who are recent high school graduates two years of free tuition along with a mentoring program that helps recipients make better decisions among higher education options; a program to support regional partnerships that bring together employers and K-12 districts; and a program that expanded the state’s last dollar scholarship strategy to adults.

PROMISING PRACTICE

Hawai‘i P-20 Partnerships for Education

This statewide partnership led by the Executive Office on Early Learning, the Hawai‘i State Department of Education, and the University of Hawai‘i System works to strengthen the education pipeline from early childhood through higher education in order to increase the share of working-age adults (25 to 64) with a two- or four-year college degree from 46 to 55 percent by the year 2025. One of many integrated strategies to meet this goal is to improve college graduation rates, particularly for Native Hawaiians, low-income students, and those from underserved regions and populations. To do so, the University of Hawai‘i System responded by creating a data-driven program to help students track their progress toward completion, review degree requirements and milestone courses along their academic pathway, and explore the impact of scheduling decisions and changes in major on the time it will take them to graduate. The university also created 15 to Finish, a campaign that encourages students to take 15 credits per semester. The four-year graduation rate at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (the system’s largest campus) for first-time, full-time students who started college in fall 2012 was 32 percent, compared with 17.5 percent six years earlier.

Strengthening Pre-K-12

The main focus of this report is the work that must be done at colleges and universities to ensure the future of American undergraduate education. These institutions bear the heaviest burden for improving students’ educational experiences along the pathway to success. But undergraduate education is built on a foundation of primary and secondary school education that is itself in need of strengthening. It is difficult to think of anything that could do more to increase opportunities for more equal and more effective education at the postsecondary level than making improvements to early and K-12 education. The Commission urges that the nation take the long view that an individual’s path toward college completion begins at birth and that the life circumstances into which one is born still substantially affect one’s chances of earning a college degree and one’s later life experiences, even with strong efforts at later stages. The goal of increasing college attainment rates is inextricably linked to the education and care children receive from their families and communities beginning at a young age—including the willingness or ability of parents to read regularly to their toddlers, access to high-quality prekindergarten programs, and the availability of good healthcare and nutrition in a safe and supportive environment. Similarly, if they are to meet their full potential, students from all backgrounds need to encounter high-quality coursework and skillful classroom instruction and will benefit from academic and social supports throughout their elementary and secondary school experiences. Community-based afterschool programs often serve a critical role in helping young people build the skills and attributes necessary for academic success—especially for students from low-income, historically underrepresented backgrounds. The Commission is encouraged by the continual increase in overall national high school graduation rates and college entry rates but remains concerned that these rates are unequal across student populations and that too many high school students are unprepared for college-level academic work.

In acknowledging these realities, the Commission does not mean to imply that nothing can be done to improve college success until the precollege experience is transformed. It is the responsibility of all the powerful institutions in American society to bend their efforts toward improving prospects for the next generation.

In that spirit, the Commission affirms that colleges and universities have the responsibility to advance the cause of better precollege education. What a particular college can do depends on its circumstances. Many open access universities and community colleges can work directly with teachers and administrations in their local communities to clarify expectations and smooth pathways. High school students should have opportunities and supports to engage in college learning, since dual enrollment and early college initiatives have been shown to improve college readiness, reduce the need for remediation, and increase persistence and completion. Some universities have large schools of education whose students are a big part of the region’s teaching force. These institutions need to ensure that their students are well equipped for the work they will take up. The wealthiest and most-selective schools can invest in actively recruiting students from disadvantaged backgrounds throughout the nation but can also help neighboring communities to advance opportunities for all college-going youth. Lastly, the most fundamental and important way every college and university can help create stronger educational experiences at the P-12 levels is to ensure that their own students are receiving a high-quality, broad-based education: the vast majority of credits that college students take to become teachers are in the arts and sciences, not education courses, and aspiring teachers must have a strong and deep understanding of their subject-matter knowledge as a starting point to be effective.

Texas community colleges aggressively pursue dual-credit partnerships with area high schools. In 2015–2016, more than 133,000 Texas high school students enrolled in dual-credit courses, up from 17,800 in 2000. South Texas College, a predominantly Hispanic-serving community college, has one of the largest dual-credit efforts in the state, partnering with 24 districts and about 80 high schools, including 30 autonomous Early College High Schools, which enable participating students to earn up to 60 hours of college credit during their high school years. Minneapolis Public Schools’ My Life Plan initiative started in 2006 and works with students starting in middle school to explore and develop academic plans and career paths.

College Access: Still a Concern

Although less directly related to the issue of college completion, access to college, and to which colleges, is still a concern. Although undergraduate student enrollment grew dramatically over the past several decades and is increasingly diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, including students of all ages and backgrounds, many continue to face significant barriers to the pursuit of a college credential. Of increasing concern is access for students from low-income families, students from rural areas, adult students, Black and Hispanic students, and men.77

The barriers that preclude students from going to college fall into four broad categories: precollege academic struggles; financial hurdles; low college awareness and/or aspirations; and an inability to complete administrative requirements such as applying for financial aid. Students often lack the support and structure they need to be able to navigate burdensome processes of applying to college and managing institutional bureaucracies. Inadequate information and advising present important obstacles to success, especially for members of disadvantaged groups. As a result, the transition from high school or the workplace to college can be complex, if not opaque, to potential applicants, resulting in too many costly financial decisions and poor choices about which institutions to attend and which programs to select. For adults, often without even the limited assistance high school guidance counselors can provide, finding and receiving effective guidance and support may be even more difficult.

Wherever possible, institutions and government agencies should make available clear information about program completion rates and simplify the application process, as well as the procedures for receiving financial aid, so that qualified students from low-income or disadvantaged backgrounds can apply to the programs in which they will likely succeed. To use the language of behavioral economics, there are many advantages to finding ways to “push” information and advice to potential students, rather than making them try to find it for themselves. More generally, all college-going students (and their families) should have easy access to information about their chances of graduating from the college program they intend to enroll in, as well as an understanding of their postgraduation employment or graduate study prospects. A lack of knowledge about their postgraduation prospects is a source of deep frustration for many graduates. Much work is required to help students understand the link between the courses they take and their ability to obtain a good job or an opportunity to continue their education.

But beyond access to clear and useful information, high-quality and sufficient advising and mentoring are key.78 Information needs to be coupled with active advising and guidance along the way. Therefore, institutional practices and state and federal policy responses should focus on solutions that are comprehensive in nature and address multiple, rather than individual, barriers.

ENDNOTES

43. Community College Research Center, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/what-we-know-about-developmental-education-outcomes.pdf.

44. Education Reform Now, https://edreformnow.org/policy-briefs/out-of-pocket-the-high-cost-of-inadequate-high-schools-and-high-school-student-achievement-on-college-affordability/.

45. The Education Trust, https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/TheRisingTide-Do-College-Grad-Rate-Gains-Benefit-All-Students-3.7-16.pdf.

46. William G. Bowen, Matthew M. Chingos, and Michael S. McPherson, Crossing the Finish Line: Completing College at America’s Public Universities (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009).

47. National Center for Education Statistics, 2016 Digest of Education Statistics, Table 326.10.

48. National Center for Education Statistics, 2016 Digest of Education Statistics, Table 326.20, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d14/tables/dt14_326.20.asp.

49. See A Primer on the College Student Journey, 10, note 17.

50. Wendy Erisman and Patricia Steele, “Adult College Completion in the 21st Century: What We Know and What We Don’t,” Higher Ed Insight, June 2015, 2.

51. National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ruraled/tables/b.3.b.-1.asp.

52. Rural Education at a Glance, 2017 Edition (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture, April 2017), https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/83078/eib-171.pdf?v=42830.

53. National Research Council, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2014), doi: 10.17226/18613.

54. Bureau of Justice Statistics, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p15_sum.pdf.

55. See, for example, Davis Jenkins, Hana Lahr, and John Fink, Implementing Guided Pathways: Early Insights from the AACC Pathways Colleges (New York: Community College Research Center, 2017), https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/implementing-guided-pathways-aacc.html; and MDRC, How Does the ASAP Model Align with Guided Pathways Implementation in Community Colleges? (New York: MDRC, 2016), http://www.mdrc.org/publication/how-does-asap-model-align-guided-pathways-implementation-community-colleges.

56. Thomas Bailey, Shanna Smith Jaggars, and Davis Jenkins, What We Know about Guided Pathways (New York: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center, 2015).

57. Susan Scrivener, Michael J. Weiss, Alyssa Ratledge, Timothy Rudd, Colleen Sommo, and Hannah Fresques, Doubling Graduation Rates (New York: MDRC, February 2015), http://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/doubling_graduation_rates_fr.pdf.

58. Henry M. Levin and Emma Garcia, Benefit Cost Analysis of Accelerated Study In Associate Programs (ASAP) of the City University of New York (CUNY) (New York: Center for Benefit-Cost Studies of Education, May 2013), http://www.nyc.gov/html/ceo/downloads/pdf/Levin_ASAP_Benefit_Cost_Report_FINAL_05212013.pdf.

59. Public Policy Institute of California, http://www.ppic.org/main/publication_quick.asp?i=1197#fn-1; and The California State University, https://www2.calstate.edu/csu-system/why-the-csu-matters/graduation-initiative-2025.

60. Jessie Brown and Deanna Marcum, “Serving the Adult Student at University of Maryland University College,” Ithaka S+R, June 9, 2016, doi: 10.18665/sr.282666.

61. See A Primer on the College Student Journey, 41, note 71.

62. See ibid., 41, note 72.

63. See, for example, Bowen, Chingos, and McPherson, Crossing the Finish Line; John Bound, Michael F. Lovenheim, and Sarah Turner, “Increasing Time to Baccalaureate Degree in the United States,” Education Finance and Policy 7 (4) (Fall 2012): 375–424, doi: 10.1162/EDFP_a_00074; and D. Shapiro, A. Dundar, P. K. Wakhungu, X. Yuan, A. Nathan, and Y. Hwang, Time to Degree: A National View of the Time Enrolled and Elapsed for Associate and Bachelor’s Degree Earners (Herndon, Va.: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, September 2016), https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SignatureReport11.pdf.

64. Ashley A. Smith, “Credits Up with 15 to Finish,” Inside Higher Ed, May 23, 2017.

65. Bailey, Jaggars, and Jenkins, What We Know about Guided Pathways, 45.

66. NSSE tracks the benchmark “enriching educational experiences.” CCSSE tracks “support for learners.”

67. Jessie Brown and Martin Kurzweil, Instructional Quality, Student Outcomes, and Institutional Finances (Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education, 2017), http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/Instructional-Quality-Student-Outcomes-and-Institutional-Finances.pdf.

68. Wisconsin Hope Lab, http://wihopelab.com/publications/investing-in-student-completion-wi-hope_lab.pdf.

69. Stanley S. Litow, “Work Study and College Affordability: Time for a Closer Look,” https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/work-study-and-college-affordability-time-for-a-closer-look/.

70. Melinda Mechur Karp and Georgia West Stacey, What We Know about Nonacademic Student Supports (New York: Community College Research Center, 2013).

71. D. Shapiro, A. Dundar, P. K. Wakhungu, X. Yuan, and A. Harrell, Transfer and Mobility: A National View of Student Movement in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2008 Cohort (Herndon, Va.: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, July 2015), https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SignatureReport9.pdf.

72. Davis Jenkins and John Fink, Tracking Transfer: New Measures of Institutional and State Effectiveness in Helping Community College Students Attain Bachelor’s Degrees (New York: Community College Research Center, January 2016), https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/tracking-transfer-institutional-state-effectiveness.pdf.

73. See, for example, The Transfer Playbook: Essential Practices For Two- and Four-Year Colleges (New York: Community College Research Center, 2016), http://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/transfer-playbook-essential-practices.pdf; and National Conference of State Legislatures, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/educ/student-transfer.pdf.

74. Sophie Quinton., “Why Central Florida Kids Choose Community College,” The Atlantic, February 10, 2014.

75. Massachusetts Department of Higher Education, http://www.mass.edu/strategic/comp_transferpathways.asp.

76. Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, http://www.wiche.edu/passport/about/overview.

77. See A Primer on the College Student Journey for a full discussion of college enrollment rates.

78. See, for example, Mandy Savitz-Romer and Suzanne Bouffard, Ready, Willing, and Able: A Developmental Approach to College Access and Success (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2012); Daniel Klasik, “The College Application Gauntlet: A Systematic Analysis of the Steps to Four-Year College Enrollment,” Research in Higher Education 53 (5) (August 2012): 506–549, doi: 10.1007/s11162-011-9242-3; Andrea Venezia and Laura Jaeger, “Transitions from High School to College,” Future Child 23 (1) (Spring 2013): 117–136; Scott Carrell and Bruce Sacerdote, “Why Do College-Going Interventions Work?” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9 (3) (2017): 124–151, doi: 10.3386/w19031; and Lindsay C. Page and Judith Scott-Clayton, “Improving College Access in the United States: Barriers and Policy Responses,” Economics of Education Review 51 (2016): 4–22, doi: 10.3386/w21781.