The Rise and Decline of Global Nuclear Order?

The Rise and Decline of Global Nuclear Order?

The first half century of the nuclear age witnessed the gradual construction of a global nuclear order designed to mitigate nuclear dangers, inhibit arms racing, and prevent the spread of nuclear weapons to additional states. Spurred by the experiences, the dangers, the crises, the near misses, and the frightening risks on display in the early years of the Cold War, sustained efforts were made, in McGeorge Bundy’s vivid phrase, “to cap the volcano.”1 The time had arrived, Bundy wrote in 1969, for the two great nuclear superpowers “to limit their extravagant contest in strategic weapons,” a contest that had “led the two greatest powers of our generation into an arms race totally unprecedented in size and danger.” In the subsequent twenty-five years after Bundy’s appeal, an increasingly elaborate and institutionalized arms control process produced, with many ups and downs, a detailed web of constraints on the nuclear behavior of the superpowers. The articulated goal was to stabilize the superpower nuclear balance by reinforcing mutual deterrence. The vast nuclear arsenals of the superpowers, however, were not the only source of nuclear danger. In a world in which the number of states armed with nuclear weapons was slowly growing and many additional states had interest in acquiring such weapons or the technology to produce them, there was reason, as Albert Wohlstetter warned in 1961, to be “concerned with the enormous instabilities and dangers of a world with many nuclear powers.”2 Such a world—“life in a nuclear armed crowd”—Wohlstetter wrote in a later famous study, was widely believed to be “vastly more dangerous than today’s world.”3 The desire to prevent this unattractive world led to the negotiation of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), which entered into force in 1970, and to the subsequent development of an associated regime intended to create legal and technical barriers to the spread of nuclear weapons. Thus, in reaction to the major perceived dangers of the nuclear age, there emerged what Lawrence Freedman calls the “twin pillars” of the global nuclear order: mutual stability in the major nuclear rivalry and nonproliferation to inhibit or prevent the spread of nuclear weapons to additional states.4

By the end of the Cold War, mutual deterrence and strategic arms control had been deeply embedded in the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union, and most states in the international system had, by joining the NPT, undertaken a legally binding pledge not to acquire nuclear weapons. The collapse of the Cold War structure and the end of reflexive hostility between Moscow and Washington seemed to suggest that a much more cooperative international security system might be possible and that a golden age of ambitious arms control might beckon.5 To be sure, there were still worries about nuclear dangers and still debates about the effectiveness of the NPT system, but in general there was optimism about what President George H. W. Bush labelled “the new world order.” “The winds of change are with us now,” Bush concluded confidently in his moving and triumphant State of the Union Address in January 1991.6 A safer world, in which nuclear dangers would be contained by cooperative management, seemed to be at hand—or at least possible.

Nearly three decades later, it is evident that such hopes for a benign nuclear order have been dramatically disappointed. Harmony and cooperation among the major powers have not been preserved, a golden age of arms control and disarmament has not arrived, and the nonproliferation norm has not been universally respected. Instead, Russia’s relations with the United States and the West have grown difficult and sometimes toxic. China’s rise has added a significant complication to the nuclear calculations of Washington and Moscow. Several new nuclear-armed states have emerged, creating complicated and unprecedented regional nuclear dynamics, while protracted crises over the nuclear ambitions of Iran and North Korea have called into question the effectiveness of the NPT regime. Important pieces of the arms control framework inherited from the Cold War era have been rejected or jettisoned while others are undermined and jeopardized by contentious compliance disputes—and at present there appears to be little serious interest in reviving the arms control process, either bilaterally or multilaterally. Meanwhile technological advances in surveillance and accuracy have the potential to erode the survivability of deployed nuclear forces and thereby undermine the deterrence stability that has been one of the pillars of the global nuclear order. Compared to the high hopes of 1991, the current state of the global nuclear order is shockingly worrisome: political relations are frayed, stability is jeopardized, and arms control has deteriorated. The potential implications are enormous. As Gregory Koblenz argues in his recent analysis of the evolving nuclear scene, the United States could find itself “trapped in a new nuclear order that is less stable, less predictable, and less susceptible to American influence.”7

How did we arrive at this point and what are the forces that are shaping the negative evolution of the global nuclear order? In what follows, I provide broad-brush sketches of three phases of the nuclear age, sketches that demonstrate movement from an unregulated and highly competitive environment to one that gradually becomes highly regulated and collaboratively (sometimes cooperatively) managed. What has come to dominate the story is the striking turn in the narrative arc in recent years toward a less regulated and more contentious third phase in the history of the global nuclear order. Old concerns (such as missile defense) have resurfaced while new problems (such as multilateral deterrence) have arisen. It is not entirely clear yet where we are headed but there should be no doubt that fundamentally important questions should be on the agenda. Are we going to be living in a nuclear world that is more laden with friction, more multilateral, less stable, less constrained by negotiated agreement, and possibly populated with additional nuclear-armed actors? Will some of the undesirable characteristics of the early years of the nuclear age re-emerge? If so, what can be done to address the emerging nuclear dangers? If we are headed into or are already living in a new nuclear age, how can it be managed safely and prudently? A brief examination of the history of the nuclear order provides the context for and demonstrates the significance of these questions.

Unmanaged Competition, 1945–1970: Racing to Oblivion?

In the beginning, there was not order but unmitigated competition. For the first quarter of a century of the nuclear age, nuclear forces evolved in an unregulated environment. Serious dialogue between the great Cold War protagonists was virtually nonexistent. States were unconstrained by arms control agreements. There were few norms or tacitly agreed codes of conduct. To the extent that order existed at all, it emerged from the uncoordinated unilateral steps and choices of states acting on the basis of their own perceived self-interest. For the two Cold War superpowers, the result was a world of intense arms racing and recurrent nuclear crises. Driven by fear, by the opacity of the existing military balance, by uncertainty about the plans and motives of the other side, and by concern about the adequacy of deterrent postures, the two nuclear superpowers rapidly expanded and modernized their nuclear forces.

The formative nuclear strategists of this era quickly came to the conclusion that nuclear weapons were best understood as instruments of deterrence. Remarkably, Bernard Brodie articulated the core logic almost immediately after World War II in an essay initially drafted late in 1945. Because no gain would be worth suffering a devastating nuclear attack, Brodie argued, aggressors would refrain from nuclear attack if threatened with retaliation in kind. Hence the great imperative of the nuclear age: “The first and most vital step in any American security program for the age of atomic bombs is to take measures to guarantee ourselves in case of attack the possibility of retaliation in kind.”8 Inexorable logic suggested that if other nuclear powers heeded the imperative to possess nuclear retaliatory capabilities, a condition of mutual deterrence (later codified in American doctrine as mutual assured destruction, or MAD) would exist. If nuclear rivals had confidence in the adequacy and survivability of their respective retaliatory capabilities, the nuclear balance would be stable, meaning neither side would have incentives to use nuclear weapons first. In this way, a kind of nuclear order would emerge as the Cold War evolved, so long as the United States and the Soviet Union satisfied the requirements of deterrence—as both strenuously sought to do. As Lawrence Freedman observes, “The logic of the nuclear stalemate was to neutralize the effects of the arsenals. There was no premium in initiating nuclear war. Each arsenal cancelled out the other.”9

With hindsight, we know that the resulting order—the logic of nuclear stalemate—sufficed to prevent the use of nuclear weapons despite years of dramatic political contention and military conflict (notably Korea and Vietnam). But it was also an order marked by stresses, dangers, and disadvantages. Nuclear weapons were never used but the arms competition between the nuclear superpowers was extremely intense and the confrontations between them seemed, both at the time and in retrospect, to be perilous.

Powerful arms race dynamics propelled the Soviet-American nuclear competition. At least five reinforcing forces were in play. First, the overwhelming importance of preserving second strike capabilities against current and future threats created incentives for expansion and redundancy; a large and diverse nuclear arsenal provided insurance against the risk of being victimized by a successful first strike and allayed strategic concerns that the other side’s expanding and improving forces might pose a credible threat to one’s own deterrent force. Second, each side was keen to ensure its own second-strike capability but was not willing to accept without resistance the retaliatory forces of the other side. Rather, both Moscow and Washington embraced operational nuclear doctrines—under the rubric of counterforce and damage limitation—that targeted the nuclear forces of the other side. Hence, the enormous growth in the size of the arsenals represented an expansion of the number of targets, requiring larger forces to ensure that all targets could be covered—a self-reinforcing cycle. The obvious intense contradiction between the imperative to possess a survivable deterrent force and the powerful instinct to target the deterrent forces of the other side not only drove up numbers but produced recurrent concerns about vulnerability and instability.10

Third, these potent doctrinal impulses produced strong interaction effects as the nuclear plans and behavior of the Cold War protagonists influenced one another—what came to be known as the action-reaction phenomenon.11 But in an atmosphere of hostility, distrust, and uncertainty about future plans, there was a tendency to worry about the worst-case, to prepare to match what the opponent might do next, to fear that the future threat could turn out to be larger and more effective than expected. Prudent policy-makers, it was believed, would feel the need to be ready for the worst-case scenario, resulting in what might be more accurately described as an action-overreaction dynamic. As George Rathjens wrote in 1969, “the action-reaction phenomenon, with the reaction often premature and/or exaggerated, has clearly been a major stimulant of the strategic arms race.” The pattern of overreaction, Rathjens observed, produces “an arms race with no apparent limits other than economic ones, each round being more expensive than the last.”12 The unknown future cast a powerful shadow as fears of an ever larger and ever more sophisticated and effective nuclear arsenal in the hands of the other side shaped the perceptions and decisions of nuclear policy-makers; the long timelines associated with the procurement of major systems meant that today’s choices were inevitably framed in the context of an unknown future threat.

Fourth, one particular form of the action-reaction model, the offense-defense arms race, was thought to be operating powerfully. For deterrence to work, nuclear forces needed not only to be able to survive an attack in some number, but the surviving forces needed to be able to penetrate the enemy’s defenses—otherwise the necessary retaliation in kind is questionable and may not be sufficient to deter.13 Even an imperfect first strike could significantly degrade an arsenal and might reduce the surviving retaliatory force to such an extent that it makes the problem of defense against retaliation much more tractable. At the time, missile defenses were still limited and not highly effective, but no one knew what advances might be made in the future. A breakthrough could undermine deterrence and give one side a strategic advantage. The answer to the potential threat of future effective defenses was, once again, an expansion of offensive forces. If the offensive force was large enough, it would always be possible to exhaust a missile defense system no matter how effective it might be. Moreover, in this era (as at present) it was considerably cheaper to acquire additional offensive forces than to deploy missile defense interceptors. “In a competition with a determined and resourceful adversary,” Rathjens explained in response to impending U.S. decisions in the late 1960s about deploying missile defense, “the advantage in an offense-defense duel would still lie with the offense.” Nevertheless, the urge to defend is very strong and the choice to remain defenseless is often unacceptable in domestic political terms even if sensible in strategic terms. Hence, both the United States and the Soviet Union were working on missile defense systems and their planning for nuclear forces had to take into account possible defensive deployments in the future. The notion of an offense-defense arms race envisioned a future in which ever larger and better missile defense systems would be offset by ever larger and more sophisticated offensive arsenals—with the expansion of offensive forces driven by the imperative of deterrence. This would produce an upward spiral in the nuclear competition without eliminating the nuclear threat. As Rathjens concludes, “it appears virtually certain that at the end of all this effort and all this spending neither nation will have significantly advanced its own security.”14

Finally, at least in the United States nuclear policy-making was driven in part by a politically motivated fear of falling behind and being (or looking) inferior. In strategic terms, exact numbers might not be significant and possession of a secure second-strike capability should make additional forces unnecessary or superfluous. However, there was concern about the international optics of having smaller forces; friends and foes might perceive the United States to be the weaker power, with negative consequences for Washington’s ability to operate in the world.15 Similarly, in the American domestic political context, the Soviet achievement of numerical advantages by the 1970s was disturbing and for elected officials there was little to be gained by supporting alleged inferiority. Codifying those Soviet advantages in arms control agreements was particularly controversial and provoked intense criticism. Writing decades after the debates about ratifying the SALT I agreements, for example, Henry Kissinger is still visibly frustrated by the “amazing tale” of the claim that in the SALT negotiations the Nixon administration had “conceded an inequality.” Kissinger explains that “inequality was one of those code words that create their own reality,” a reality that undermined support for the Nixon-Kissinger arms control policy and produced the impression, as Kissinger himself puts it, “that what the Administration was defending was a ‘missile gap’ disadvantageous to the United States.”16 In short, internal political considerations joined strategic calculations in promoting vigorous competition in the nuclear relationship.

A further confounding factor was the possibility that nuclear weapons might spread to additional countries. From the earliest days of the nuclear age, it was understood that other states might choose to pursue and deploy nuclear arsenals, resulting in what Brodie, in 1946, described as “multilateral possession of the bomb.”17 This was an option available to any state that possessed or could develop or acquire the technical and financial resources necessary for a nuclear program. While the United States and the Soviet Union were primarily preoccupied with each other, it was recognized that in the not-too-distant future there could be a number of nuclear-armed states. By 1960, Washington feared that there might be as many as twenty-five nuclear weapon states within five to fifteen years—a prediction that John Kennedy noted during his presidential campaign and that President Kennedy later highlighted in a memorable press conference in March of 1963.18 Here, then, was another large and worrisome uncertainty: the U.S.-Soviet rivalry might become embedded in a multilateral nuclear order that could involve many (large and small, stable and less stable, responsible and irresponsible) actors, regional nuclear balances, multidirectional fears of attack, and concerns about the stability of a complicated overall system of nuclear interactions. Both Moscow and Washington feared and opposed this outcome, a deeply held shared interest that produced considerable cooperation between them on nonproliferation even in the darker days of the Cold War.19 But policy-makers and nuclear planners on both sides had no choice but to consider the implications of life in Wohlstetter’s “nuclear-armed crowd.” This was another unsettling feature of the nuclear order in the first quarter century of the nuclear age.

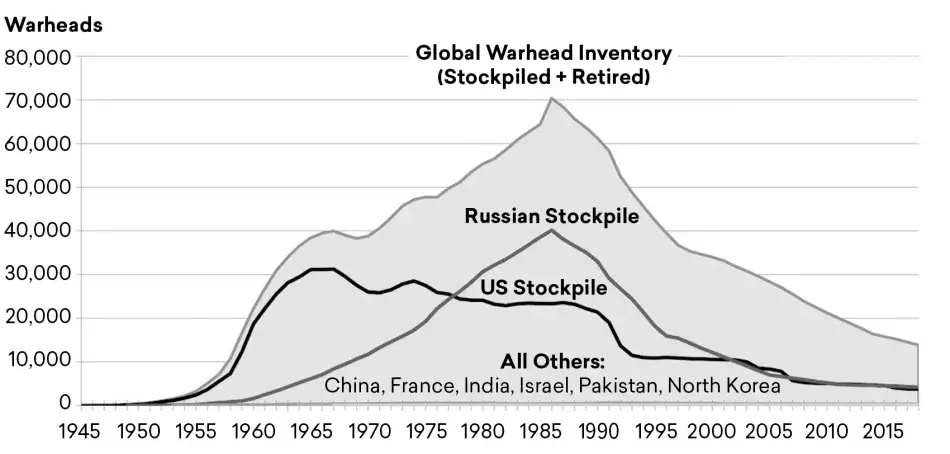

The operation of this set of powerful forces had three broad effects. First, there was a prodigious accumulation of weapons—to a level that today seems irrational. One small nuclear weapon devastated Hiroshima, but the superpowers eventually deployed tens of thousands of weapons, nearly all of them many times more powerful than the bombs dropped in 1945. By the time this gluttonous acquisition of nuclear weapons peaked in 1986, there were more than seventy thousand nuclear weapons deployed by the superpowers—more than thirty thousand in the American arsenal and nearly forty thousand in the Soviet arsenal.20 This extraordinary amassing of weapons represented an unimaginable aggregation of destructive power—leading to concerns that any substantial nuclear exchange between the Soviet Union and the United States could seriously damage the global ecosystem by producing a “nuclear winter” as enormous quantities of dust and debris in the atmosphere blocked the sun and produced a cooling of the planet.21 Advocates of arms control believed that this immense buildup increased dangers and wasted resources while producing no net improvement in security. An intense quantitative arms race was one of the hallmarks of the unregulated phase of the nuclear age. And the momentum of this build-up continued well into the 1980s.

Second, the scramble for advantage and the fear of disadvantage led to the nuclearization of nearly everything. Long-range bombers and ballistic missiles were, of course, the mainstays of the strategic nuclear competition. But by the 1960s, nuclear weapons were being deployed throughout the U.S. and Soviet militaries in every armed service and on nearly every conceivable means of conveyance. Gravity bombs were provided for tactical aircraft. Shorter-range missiles and cruise missiles were armed with nuclear weapons. Nuclear air defense interceptors and nuclear torpedoes were deployed. In addition, an array of so-called battlefield nuclear weapons was developed, including nuclear artillery shells, nuclear land mines, and man-portable nuclear weapons. The M28/M29 Davey Crockett, for example, was a recoilless rifle, handled by a three-man crew, that fired a W54 warhead weighing 51 pounds in a projectile that was 11 inches in diameter and 31 inches in length; between 1961 and 1971, the Davey Crockett was deployed in both Germany and South Korea.22 At the peak of this nuclearization in the 1970s, the United States possessed some 7,600 tactical nuclear weapons, of which 7,300 were deployed with U.S. forces in Europe.23 Every domain of warfare—ground forces, naval deployments, tactical air—became part of the nuclear equation. Along with the pervasive deployment of nuclear weapons came elaborate doctrinal explorations about how the various levels of nuclear capability were related to one another in ladders of escalation and whether it might be possible to engage in varieties of limited nuclear war without escalating to all-out nuclear exchanges.24 The unrestrained competition widened the horizons of the nuclear debate and brought more menacing scenarios and possibilities into view.

Third, the vast accumulation and wide distribution of weapons were accompanied by rapid innovation and a fast pace of nuclear modernization. At the outset of the era, medium-range bombers were the primary delivery system, but were soon supplanted by intercontinental bombers. Starting in 1951, the United States invested in more than two thousand B-47 medium range bombers, but in 1955 the long-range B-52 was introduced and by 1963 more than seven hundred B-52 bombers had been acquired. The Soviet Union was simultaneously charging into the missile age. The Soviet launch of an orbiting satellite in October 1957 demonstrated Moscow’s progress and produced in the United State the shocked belief that it was lagging behind in the missile field—producing deep fears of a missile gap. The U.S. missile program was galvanized and early in his administration President Kennedy decided to deploy a thousand intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), dubbed Minuteman. In parallel, starting in 1961, ballistic missiles were deployed at sea on submarines. By the late 1960s, programs were underway to put multiple warheads on missiles and to upgrade their guidance systems to improve accuracy.

The large and redundant strategic forces that emerged on both sides provided grounds for thinking that second-strike forces would survive any attack and deterrence would therefore be effective. The pace of innovation and modernization, however, was worrisome and disruptive, and gave rise to fears that large and dangerous vulnerabilities might emerge or exist or that asymmetric capabilities might give significant or even decisive advantage to one side. Reliance on medium-range bombers meant utilizing air bases within range of the Soviet Union that were vulnerable to attack. Long-range bombers were potentially vulnerable to short-notice attacks by ICBMs. Even missiles in hardened silos were vulnerable if attacking missiles could strike accurately enough. Command and control arrangements for nuclear forces could become vulnerable to crippling “decapitation attacks.” Rapid modernization brought all these concerns into view, producing a perennial debate about the survivability and adequacy of deterrent forces and a pattern of lurching from one vulnerability crisis to the next. By the mid-point of the Cold War, the United States was in the midst of a serious scare over the possible vulnerability of its ICBM force.25 While the heated quantitative arms race produced enormous numbers, the intense qualitative race generated endless anxiety and repeated scares about possible instability in the nuclear balance.

The compulsion to compete quantitatively and qualitatively produced what came to be labelled arms race instability. This was an unfortunate circumstance: costly, potentially dangerous, and producing questionable gains in security while raising fears of instability. But an even larger concern arose from the repeated diplomatic confrontations between the nuclear antagonists, which raised the risk of military escalation and brought the possibility of nuclear use into view. In one collision after the next—the Korean War, Quemoy and Matsu, Berlin—nuclear weapons cast a worrisome shadow. What is generally regarded as the moment of maximum danger—namely, the Cuban Missile Crisis—came in October 1962. The incredibly intense standoff between Moscow and Washington over the Soviet Union’s deployment of missiles in Cuba brought the world to the brink of nuclear war—or so it was believed—and subsequent revelations exposed dangers not fully understood at the time. This frightening near-miss highlighted the peril of nuclear crises. “Events were slipping out of their control,” commented Robert McNamara in one of his countless exhortations about the lessons of the 1962 crisis, “and it was just luck that they finally acted before they lost control, and before East and West were involved in nuclear war that would have led to destruction of nations. It was that close.”26

Two large concerns were reinforced by the Cuban Missile Crisis. One was the importance of managing crises carefully and effectively; “crisis management” became almost a field unto itself—abetted by the claim that disaster had been avoided in 1962 because President Kennedy and his team had handled the affair so deftly. The other, more fundamental, concern had to do with the problem of crisis instability—the fear that in a crisis there might exist particular temptations to strike if striking first with nuclear weapons would confer advantage, especially if each side feared that the other might strike first. Thomas Schelling warned in 1960 that even a small incentive to strike first could be magnified by this dynamic, which he called the reciprocal fear of surprise attack: “Fear that the other may be about to strike in the mistaken belief that we are about to strike gives us a motive for striking, and so justifies the other’s motive.”27 This was another argument for robust deterrence: the answer to crisis instability was survivable nuclear forces that would guarantee that a surprise attack would be met with unacceptable retaliation. After Cuba, the power of this analysis was fully understood.

In sum, nuclear order in the first twenty-five years of the nuclear age took the form of unregulated competition in which the only significant constraints were budgetary and technological and in which the primary moderating force was the mutual deterrence that arose out of each side’s unilateral efforts to neutralize the nuclear forces of the other. This was a nuclear order that, as it evolved, came to be marked by massive numbers of nuclear weapons, pervasive nuclearization of military forces and doctrines, and recurrent dangerous and sometimes frightening crises. Gradually, however, a school of thought emerged that suggested that the costs and dangers of the existing nuclear order could be contained and reduced if negotiated constraints could be achieved.

Managed Rivalry, 1970–2000: Building an Architecture of Restraint

It would be incorrect to suggest that there was a magical transformation of the nuclear order, after which all was well. On the contrary, the superpower rivalry remained intense, nuclear forces remained substantial, efforts to escape the implications of mutual deterrence endured, bruising diplomatic confrontations continued, domestic controversies over nuclear policy and arms control were common, and worries about nuclear proliferation persisted. After the unfettered competition of the first quarter century following World War II, though, the next several decades were an era of arms control. Starting in the late 1950s, a group of strategists began to analyze and advocate for arms control, suggesting that negotiated constraints were both feasible and desirable.28 The aim, as then-Director of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) Alistair Buchan summarized, was “the stabilizing of mutual deterrence by taking both unilateral and multilateral action and at the same time attempting to identify and control the most dangerous features of the arms race . . . .”29 Ideas and policy concerns that had been discussed for years came to fruition in the 1960s. Prompted in part by the Chinese nuclear test in October 1964, negotiations commenced in 1965 under the auspices of the United Nations for a treaty to inhibit the spread of nuclear weapons. In the same period, efforts to launch U.S.-Soviet arms control discussions were disrupted for a time, in particular by the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968, but the strategic arms control talks finally began in November 1969, initiating a process that would continue, with minor interruptions, more or less continuously for four decades. The processes for enhancing Lawrence Freedman’s twin pillars—nonproliferation and strategic stability—were in place.

The evolution of the nuclear order was neither smooth nor harmonious. Though the United States and the Soviet Union shared an interest in preventing nuclear proliferation and in avoiding an unwanted nuclear war, their relations were contentious and marked by distrust until very late in the Cold War period. Arms control remained controversial and outspoken skeptics criticized both the broad process and the content of specific agreements.30 Nevertheless, over several decades, stretching from the late 1960s to the late 1990s, there was the gradual construction of elaborate treaty regimes that addressed both concerns about nuclear proliferation in the multilateral arena and about nuclear rivalry in the bilateral Soviet-American arena. As Richard Haas has written in characterizing this nuclear era, “reason and caution increasingly gained the upper hand.”31

The tales associated with building the web of connections and constraints are long and filled with telling details, but the essential architecture of restraint rested on four main building blocks.

Preventing the Spread of Nuclear Weapons: The Nonproliferation Treaty and Regime

Somewhat miraculously, it proved possible to negotiate a legally binding multilateral treaty that acknowledged and accepted the five nuclear weapon states that existed at the time but prohibited all other signatories from building or otherwise acquiring nuclear weapons. Across time, also perhaps somewhat miraculously, nearly every state in the international system (191 member states) signed the treaty; every state that does not possess nuclear weapons (with the single exception of South Sudan) has signed a legal instrument in which they accept a binding obligation to remain non-nuclear. The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty entered into force in 1970 and became the legal foundation for an evolving regime of technology controls and mandated inspections of nuclear facilities aimed both at preventing the spread of weapons-related nuclear technology and at discouraging the use of civilian nuclear facilities for illicit weapons-related purposes. Adaptions in the regime often came after some undesirable development or challenge to the system. After the 1974 Indian nuclear test, for example, a Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) was established to harmonize export controls on sensitive nuclear technologies and to deny weapons-related technologies to potentially worrisome recipients. Similarly, after the discovery of Iraq’s illicit nuclear weapons program in 1990, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) developed a new set of information requirements and inspection measures, enumerated in a document called the Additional Protocol, that enhanced the IAEA’s access to information and its powers of inspection. In the nearly five decades since its inception, there has been considerable evolution in the NPT regime. From the beginning, there were doubts about its sufficiency and effectiveness.32 Doubts remain even today, and the regime has been seriously tested by protracted crises involving Iran and North Korea—showing that where proliferation problems exist, they are very disruptive and troublesome and not easily addressed. Nevertheless, the unregulated order in which it was feared that nuclear weapons might spread to many states has been replaced by a nearly universal treaty that prohibits the acquisition of nuclear weapons and by an associated regime for managing and limiting the spread and use of weapons-related nuclear technology. In the 1950s and 1960s, few would have imagined that the eventual puzzle would be why there are so few nuclear-armed states nor would they have expected the emergence of a widespread norm against the acquisition of nuclear weapons.33 The assumption that a steadily growing number of states would acquire nuclear weapons was supplanted by the belief that most states would not do so. This was a profound change in the global nuclear order.

Severe Constraints on Missile Defenses: The ABM Treaty

Nascent missile defense programs in the United States and the Soviet Union had been both engines of the arms race and potentially destabilizing factors in the strategic equation between the superpowers, since they could contribute to first-strike options. In the early stages of the strategic arms control process, the most significant result was the 1972 ABM Treaty, of unlimited duration, that limited the two sides to two strategically insignificant missile defense sites.34 Interest in and explorations of missile defense persisted (most prominently with Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative program in the 1980s), but operational deployments were severely restricted by a permanent treaty. A 1974 protocol to the ABM Treaty reduced the number of permitted sites to one, and in 1975 the United States abandoned missile defense deployments altogether (though research and development continued). Regarded as the essential foundation of strategic arms control, the ABM Treaty directly confronted offense-defense interactions as an influence on nuclear decision-making by eliminating missiles defenses from the equation for the foreseeable future. This was a vast and moderating change in the character of the global nuclear order.

Limiting and Reducing Offensive Nuclear Forces: SALT, START, and Beyond

Missile defenses were only one of the factors that gave momentum to the accumulation of offensive nuclear forces. Fears of vulnerability, worries about inferiority, desires for counterforce options, and the drive for innovation and modernization were also in play. Uncertainty was a major influence: who knew how large and capable an opponent’s force might be in the future, especially when current planning had to anticipate capabilities that might exist years ahead? Starting with the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks (SALT) in November 1969 and continuing through the New START agreement of April 2010, Washington and Moscow engaged in a long series of negotiations aimed at limiting strategic offensive forces.35 These negotiations were typically slow and difficult. The agreements were sometimes disappointing and were frequently controversial. The process sometimes broke down or failed; ratification of the SALT II agreement, for example, was prevented by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

But the aggregate impact of this process was the imposition of an evolving set of increasingly significant constraints on the size and character of nuclear forces, accompanied by a verification process that reduced the opacity of the competition. The first such agreement, the Interim Agreement on Offensive Forces of 1972, established a freeze on the number of launchers—the volcano was capped and the upward spiral in the number of delivery systems was stopped, permanently as it turned out. It is commonly presumed that arms control codified rather than caused the leveling off of the Soviet-American nuclear competition, but it is also plausible that deployments could have grown even larger in the absence of limits on offensive and defensive forces. Since 1972, however, strategic nuclear arsenals have been governed by agreed limits and hence the future size of the opposing force could be known precisely with some confidence so long as the arms control framework was expected to remain intact. The Soviet Union and the United States agreed to observe the limits of the 1979 SALT II agreement even though it was never ratified. Starting in the 1980s, strategic arms control focused on reducing numbers and constraining modernization—even though the Reagan administration was skeptical of arms control and started out with a confrontational policy toward the Soviet Union. With the signature of the START I agreement of 1991 after nearly a decade of negotiation, significant reductions had been agreed upon, limits on modernization had been achieved, extensive verification measures had been accepted, and the strategic nuclear relationship was governed by a detailed treaty, including countless pages of definitions, annexes, protocols, and agreed-upon understandings. This was a remarkable change from the reality that existed in the first twenty-five years of the nuclear age.

The aim of this protracted exercise in arms control was not only to contain the arms competition between the two superpowers—that is, the promotion of arms race stability. It was also intended to inhibit the emergence of destabilizing capabilities—thus contributing to crisis stability. To be sure, neither side ever really abandoned the quest for advantage or the pursuit of usable nuclear options, but the imperative to ensure the adequacy of deterrence was fundamental. Arms control was viewed as an instrument that could strengthen deterrence and prevent threats to the deterrence system from arising. As Henry Kissinger has written, “The diplomacy of arms control concentrated on limiting the composition and operating characteristics of strategic forces to reduce the incentive for surprise attack to a minimum.”36

Arms Control as Management Process

Despite recurrent acrimony in U.S.-Soviet relations and occasional interruptions in negotiations, arms control talks became a form of institutionalized dialogue on nuclear issues. As Matthew Ambrose comments about SALT, for example,

Negotiations grew so routine that they became divorced from whatever agreement they sought to achieve next and were instead seen as a continuous process. In this process, senior policymakers on each side formulated a policy and presented and discussed these positions at formal diplomatic exchanges. These exchanges were punctuated by intermittent summit meetings by heads of state or cabinet officials. As this cycle repeated itself, policymakers primarily thought of their task as tending to the more abstract “SALT process.”37

These regularized interactions became, in effect, a mechanism for the joint management of the nuclear balance. The completely uncoordinated exertions of the 1950s and 1960s were eventually replaced by the practice of regular consultation, producing periodic agreed-upon limitations on nuclear forces. Rivalry still existed and nuclear dangers did not disappear, but the era of unbridled nuclear competition and galloping acquisition of nuclear forces was brought to an end.

Post–Cold War Promise and Progress

Arms control had proven resilient enough to weather setbacks and low moments, even during the Cold War. With the end of the Cold War, there arrived a moment of extraordinary hopefulness. Instead of intense antagonism, there was now “strategic partnership” between Moscow and Washington. As the Cold War waned and then disappeared into history, what emerged was a remarkable decade-plus of arms control. This phase commenced with the dramatic Reagan-Gorbachev summit at Reykjavik in 1986, at which the two presidents discussed both the elimination of all nuclear weapons and the banning of ballistic missiles.38 Though the two sides were unable to reach agreement on these unprecedentedly sweeping measures, Reykjavik represented a symbolic breakthrough to a much more ambitious era of arms control. Soon after came the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) agreement that eliminated an entire class of missile. This was the beginning of a retreat from the nuclearization of everything that had been witnessed in the early decades of the nuclear age. It was followed in September 1991 by an unprecedented set of reciprocal unilateral initiatives undertaken by Presidents Bush and Gorbachev (prompted in part by the August 1991 coup attempt against Gorbachev that raised concerns about control of nuclear weapons) that committed the two sides to eliminate, withdraw from service, or significantly reduce most categories of tactical nuclear weapons; particularly notable was the focus on removing tactical nuclear weapons from ground and conventional naval forces.39 The intent and effect of these initiatives was to “radically reduce” holdings of deployed tactical nuclear weapons.40 In December 1991, the United States initiated the Cooperative Threat Reduction program (also known as Nunn-Lugar) that involved intimate cooperation with and investment of U.S. taxpayer dollars in the Russian nuclear weapons establishment; it sought to secure facilities and weapons-usable nuclear materials to allay concerns that Russian nuclear assets might leak into illicit nuclear markets during the turbulent period after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This program was not without its difficulties and frictions, but it involved a degree of intimate nuclear collaboration that would previously have been unthinkable. In short order, the possibilities for arms control seemed to expand and the nuclear relationship was transformed by one unprecedented move after another.

In parallel, significant steps were taken in strategic arms control. After a difficult decade of on-again, off-again negotiations, the START I agreement was signed on July 31, 1991. Much the most complex of these agreements and containing elaborate verification provisions, START I called for significant reductions in the number of deployed strategic delivery systems and associated nuclear weapons. Soon thereafter, on January 3, 1993, yet another agreement—START II—was reached; it represented a further elaboration of the increasingly extensive network of negotiated constraints governing nuclear capabilities by introducing an important qualitative constraint: the banning of multiple warhead (MIRVed) missiles, which were regarded as potentially destabilizing because they expanded attack capabilities while also representing attractive targets for the other side.

This phase of hope and progress reached a crescendo in the mid-1990s, highlighted by one historic event and one dramatic vision. The historic event was the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995. The treaty was coming to the end of its initial twenty-five-year duration and the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference would determine whether the treaty was terminated or extended, and if extended, whether for a fixed term or indefinitely. There was no guarantee that the alchemy that had permitted the negotiation of the treaty in the late 1960s would exist in 1995 and there was plenty of indication (not least at earlier NPT review conferences) of dissatisfaction with the treaty. Hence, there was great concern in the period leading up to the 1995 conference that the outcome could well be disappointing. George Bunn, one of the leading nonproliferation experts, warned, for example, that “The obstacles to securing a lengthy extension are truly formidable….”41 The United States, for its part, mounted a major diplomatic effort to gain support for a protracted renewal of the NPT, motivated by the realization that among NPT members “many are resisting an indefinite extension.”42 At the 1995 conference itself a number of alternatives were put forward, including renewal for a single fixed period, rolling renewal for fixed periods, and renewal made conditional on greater and more tangible progress toward nuclear disarmament by the states possessing nuclear weapons. In the end, however, on May 11, 1995, the conference agreed on the indefinite extension of the NPT, thus putting the legal foundation of the nonproliferation regime on sound permanent footing.43 This was seen as a major victory: the demise of the NPT had been avoided and instead the NPT regime entered “a new era.”44 There were still nonproliferation problems on the agenda, of course, and efforts to improve the regime continued, but with the indefinite extension of the NPT the nonproliferation pillar seemed well-entrenched. Moreover, the deliberations over the NPT gave impetus to the negotiations on nuclear testing, with non-nuclear weapon state members of the NPT pressing the nuclear-armed states to take tangible steps toward disarmament, as called for in Article VI of the NPT. The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) was signed in September of 1996.

The landmark step in nonproliferation was soon followed by the emergence of a dramatic vision of progress in strategic arms control. At their summit in Helsinki in March of 1997, Presidents Clinton and Yeltsin agreed on a framework for the upcoming START III negotiations that went well beyond earlier agreements.45 The Clinton-Yeltsin framework envisioned not only further substantial reductions in nuclear forces, but also, for the first time, a direct focus on warheads and nuclear materials (in contrast to earlier agreements that focused overwhelmingly on delivery systems). The negotiation was (again, for the first time) to address tactical as well as strategic nuclear weapons, and to cover delivery systems (such as sea launched cruise missiles) that had been excluded from earlier agreements. There was an emphasis on trying to achieve the irreversibility of reductions by creating a cooperative and transparent program for the dismantlement of warheads withdrawn from service and to secure and manage the nuclear materials extricated from dismantled warheads. Clinton and Yeltsin established the goal of creating a nuclear arms control regime of permanent duration. The parameters for negotiation agreed by the two presidents at the Helsinki summit aimed at nothing short of a comprehensive, cooperative, highly transparent, permanent, treaty-based regime for managing the nuclear relationship between the United States and Russia.46 If the Reagan-Gorbachev summit at Reykjavik was, in terms of ambition, the pinnacle of Cold War arms control, the Clinton-Yeltsin summit at Helsinki was the high-water mark of post–Cold War arms control. An agreement based on the Helsinki parameters would be unprecedentedly ambitious and transformative.

In sum, a fertile dozen years, spanning the end of the Cold War and the emergence of the post–Cold War era, stretching from Reykjavik 1986 to Helsinki 1997, witnessed an impressive advance of arms control in multiple contexts. The negotiations were often contentious, forward movement was often hard-won, interests still collided, rivalries and antagonisms between states continued, agreements invariably attracted criticism and opposition, and policy battles were fought and sometimes lost. This is not a smooth story of steady and uninterrupted progress. Nevertheless, in aggregate, by the late 1990s, much had been achieved: an extensive, treaty-based regulatory infrastructure governed the nuclear affairs of the planet, and momentum in the direction of greater cooperation and additional constraints seemed in evidence.

The Tide Turns, 2000–2018: The Erosion of the Nuclear Order

The picture so far suggests that during the first half century of the nuclear age there was a slow and uneven but broad evolution from intense, unregulated competition to an increasingly regulated, collaboratively managed nuclear environment in which nuclear arsenals were constrained by agreement and the spread of nuclear weapons was inhibited by a negotiated regime rooted in a permanent legally binding treaty. The unregulated phase was marked by the slow but steady increase in the number of nuclear armed states, prodigious accumulations of weapons by the two main protagonists, the spread of nuclear weapons throughout the military organizations of the superpower rivals, recurrent fears of instability undermining deterrence, and frightening and risky diplomatic and military confrontations that raised risks of nuclear use. We do not have to hypothesize about what an unregulated global nuclear order—a world without arms control—might be because the first twenty-five years after the end of World War II gave us a vivid taste of that world.

The increasingly regulated phase of this history, in contrast, gradually built a global nuclear order in which the NPT had gained almost universal acceptance, the associated regime was being slowly improved, a norm of nonproliferation was thought to exist, and the emergence of the feared nuclear-armed crowd was avoided. In parallel, the superpower arsenals were dramatically reduced in size and many types of tactical weapons were withdrawn from operational deployment, qualitative limits constrained modernization, missile defense deployments were constrained to meaningless levels by negotiated agreement, nuclear dialogue was sustained and essentially institutionalized, and the nuclear relationship between Washington and Moscow had grown impressively and unprecedentedly cooperative. In the early post–Cold War era, with past antagonisms consigned to history and once unimaginable collaboration now possible, it seemed that the movement in the direction of a heavily regulated and jointly managed nuclear order would continue and deepen.

And then the tide turned. It is even possible to point to a moment when, arguably, events began to shift in a more troubling direction. On May 12, 1998, India conducted a set of nuclear tests that represented the commencement of an open program aimed at developing deployable nuclear weapons.47 Within weeks, Pakistan responded with its own nuclear tests. The two big powers in South Asia were now committed to the nuclearization of their troubled and conflict-prone relationship.48 Not since China detonated its first nuclear test in October 1964 had the nonproliferation norm been so blatantly disregarded.49 Another reversal came the following year: in October 1999, the United States Senate voted down the CTBT and has yet to ratify the agreement to this day. This multilateral instrument, hailed as a breakthrough and seen as a point of significant progress when signed in 1996, cannot enter into force until the United States (along with some others) formally adopts the treaty; hence, the treaty remains in limbo. Whatever momentum was derived from the indefinite extension of the NPT and the signing of the CTBT was soon lost.

These setbacks in nonproliferation were accompanied in 1998 by a dramatic loss of momentum in strategic arms control. With Clinton embroiled in scandal and impeachment proceedings, Russia preoccupied with a severe domestic economic crisis, and relations between Washington and Moscow increasingly complicated by NATO enlargement, Balkan crises, and other frictions, the strategic arms control process fell off the agenda. The START III negotiations were never begun and the ambitious Helsinki framework was never converted into an actual treaty governing Russian and American nuclear forces. The 2000 presidential election in the United States brought to power an administration that regarded the inherited arms control infrastructure as an “obsolete relic” of the Cold War and was determined to escape the shackles imposed on American policy by arms control treaty obligations. The Bush administration was more inclined to dismantle existing arms control arrangements than to build a more extensive web of negotiated constraints.50

Looking back two decades later, the events of 1998 look like the beginning of a long period in which difficulties, setbacks, and worrying trends outweighed occasional gains in terms of the stability and management of the global nuclear order. To be sure, the picture is not totally bleak. Two new strategic arms control agreements—the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) of 2002 and the New Start Agreement of 2010—were reached with Russia; though modest compared to the ambitions of the late 1990s, these agreements preserved the negotiated nuclear relationship between Moscow and Washington. An unprecedented agreement—the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—was put in place to constrain Iran’s nuclear program and to ease concerns about its possible acquisition of nuclear weapons (only to be renounced in 2018 by President Trump). There have been meaningful augmentations of the NPT regime, including the wide acceptance of the Additional Protocol that strengthens the safeguards system and refinements of international export controls to inhibit the spread of weapons-related nuclear technology. Nevertheless, the global nuclear order today is vastly different and more worrisome than was envisioned two decades ago. A number of trends and developments have combined to alter the trajectory of the nuclear order.

The Return of Great Power Competition

Political relations among the major powers have grown more contentious and potentially more confrontational. Most immediately, relations between the United States and Russia have grown much more toxic and have brought back into view nuclear concerns and dangers reminiscent of the Cold War—though in a very different and more difficult international context.51 The expectation that “strategic partnership” between the United States and Russia would permit sustained and unprecedented nuclear cooperation has been thoroughly disappointed. At the same time, China’s extraordinary growth in recent decades and its increasing power and assertiveness have dramatically raised the prominence of the relationship between China and the United States. These two states seem destined to be the primary rivals on the international scene in the decades to come and the potential for antagonism and confrontation is real—as evidenced by the bubbling debate in the United States about the likelihood of war with China.52 All three of these states are committed to substantial long-term nuclear modernization programs that are sure to influence one another; in the cases of the United States and Russia, they retain doctrinal inclinations that are legacies of the Cold War. The effects of competition and friction among these three can already be seen. The 2018 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review, for example, explicitly highlights the rise of great power competition and the growing power and assertiveness of Russia and China as key factors shaping U.S. nuclear policy and as core rationales for Washington’s ambitious and extremely expensive nuclear modernization program.53 Nuclear weapons are now prominent in the security policies of these states and indeed, after fading into the background after the end of the Cold War, nuclear weapons have been “relegitimized.”54 Among the most powerful nuclear-armed actors, the environment is strikingly less benign and less hopeful than was the case in 1991. This is one fundamental factor that is reshaping the global nuclear order.

Proliferation Creates Regional Nuclear Balances

The emergence of three new nuclear-armed states since 1998 has resulted in regional nuclear balances in Northeast Asia and South Asia that simply did not exist previously. The possession of nuclear weapons by a mercurial North Korean regime and the presence of nuclear weapons in the fraught and conflict-prone relations between India and Pakistan have raised a new set of risks, dangers, and potential instabilities. There is no reason to assume that regional nuclear dynamics will have the attributes that have marked the bilateral relationship between the two nuclear superpowers and no reason to be confident that more than seven decades of superpower nuclear peace will be easily replicated in regional settings.55

Multilateral Nuclear Dynamics

The rise of China and the arrival of additional nuclear-armed actors has led to the multilateralization of deterrence relationships. Where once a single bilateral nuclear relationship was the primary focus, now a set of triangular relations has become increasingly salient. The United States, Russia, and China will obviously be increasingly caught up in a three-way nuclear relationship. This can be seen clearly in the Trump administration’s insistence that future strategic arms control depends on the participation of China, despite Beijing’s emphatically declared lack of interest in such participation.56 China is simultaneously integral to a second triangle involving India and Pakistan—a “trilemma” that has been described as “inherently unstable.”57 North Korea engages in a complicated nuclear interaction with the United States but also sits in a location where China and Russia are major players. No longer can the nuclear strategy community preoccupy itself largely with the U.S.-Russia nuclear relationship. Difficult questions are becoming unavoidable. Are past concepts and practices appropriate and effective in this new setting? Can arms control work in this multilateral environment? How can this more complex situation be handled safely?

The Deterioration of Arms Control

While new challenges are arising, the regulatory framework is weakening, to the point that long-time arms control experts have suggested that perhaps the era of negotiated arms control is ending.58 “If we think of the end of the cold war as a time of relative peace among the major powers,” wrote experienced arms control negotiator James Goodby in 2001, “we should ask ourselves whether arms control could survive the peace.” His plaintive answer: “Perhaps not.”59 Much that has happened in the subsequent years has vindicated his pessimism. “Arms control,” writes Eugene Rumer, “is in trouble.”60

One of the first, and most portentous, steps away from arms control was the U.S. withdrawal from the ABM Treaty in 2002. This step eliminated what had been regarded as the essential foundation of strategic arms control and opens up the possibility that the offense-defense dynamics feared in the earlier years of the nuclear age might resurface. Missile defense deployments remain small in scope and limited in effectiveness, so the arms race dynamics should not yet be operating powerfully. Nevertheless, there are already indications that the U.S. missile defense program is having an outsized impact on the calculations of others. On March 1, 2018, for example, Russian President Vladimir Putin gave a speech in which he explicitly identified U.S. missile defense policy as one of the driving factors behind Russia’s nuclear modernization:

Now, on to the most important defense issue. I will speak about the newest systems of Russian strategic weapons that we are creating in response to the unilateral withdrawal of the United States of America from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and the practical deployment of their missile defense systems both in the US and beyond their national borders….In light of the plans to build a global anti-ballistic missile system, which are still being carried out today, all agreements signed within the framework of New START are now gradually being devaluated, because while the number of carriers and weapons is being reduced, one of the parties, namely, the US, is permitting constant, uncontrolled growth of the number of anti-ballistic missiles, improving their quality, and creating new missile launching areas. If we do not do something, eventually this will result in the complete devaluation of Russia’s nuclear potential.61

Putin proceeded to enumerate an array of nuclear acquisition programs, some quite long term, that he described as intended to neutralize the U.S. missile defense effort. China’s concern about U.S. missile defense—especially but not only that deployed in Northeast Asia—is similarly quite visible.62 Chinese President Xi Jinping has said, for example, that the U.S. missile defense program is having “a severe negative impact to the global and regional strategic balance, security, and stability.”63 But the problem is not limited to Russian and Chinese concerns about U.S. missile defense; Moscow and Beijing are working to develop their own missile defense capabilities that can discomfit American policy-makers.64 The potential for a revival of offense-defense interactions clearly exists and it may prove difficult to sustain limits at low levels on offensive forces if substantial missile defense systems are built: the death of constraints on missile defense could thus undermine future efforts at constraining offensive forces.

The abandonment of the ABM Treaty had another significant consequence. On June 14, 2002—the day after the U.S. withdrawal from the ABM Treaty took effect—Russia withdrew from the START II agreement. Moscow was unwilling to abide by START II restrictions if it was going to have to contend with U.S. missile defenses. The end of START II and its important modernization constraint meant the failure of efforts to eliminate multiple warhead missiles from the strategic calculus of the two largest nuclear-armed powers. The U.S. withdrawal from the ABM Treaty was thus a double blow to the fortunes of arms control. The long-term implications could be immense if the regulatory structure governing offensive forces continues to weaken because this represents a significant step back toward an unregulated nuclear environment.

The elimination of the ABM Treaty may be the most profound change in the arms control scene in the past two decades, but other developments compound the concern that the hard-won regulatory framework created over decades is eroding. The Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, which for two decades had facilitated deep cooperation with Russia’s nuclear establishment, was terminated completely in 2012, falling victim to increasingly contentious U.S.-Russian relations.65 The INF Agreement has been in serious jeopardy in recent years as a result of a compliance dispute triggered by new Russian systems, and also by growing U.S. interest in deploying INF in the Pacific to offset expanding Chinese capabilities. In October 2018, the Trump administration announced its intention to withdraw from the INF Agreement and on August 2, 2019, the United States formally departed the treaty.66 In addition, having disposed of the INF Agreement, the Trump administration turned its attention to the Open Skies Treaty. Originally proposed by President Eisenhower in 1955 and signed by President George H. W. Bush in March 1992, the Open Skies Treaty promoted transparency by permitting overflights of national territory and requiring that the information gathered be shared with all signatories of the agreement. Invoking ever-present complaints about Russian compliance, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced in May 2020 that the United States intends to withdraw from the treaty despite the objections of NATO European allies, who continue to see value in the arrangement.67 The formal withdrawal took place on November 22, 2020. Soon thereafter Russia withdrew from the treaty as well, leaving it without its two most important participants. Whether it might be possible to resurrect the treaty is unclear, given uncertainties about Russia’s interests and possible difficulties in obtaining ratification from the U.S. Senate, which has developed a pronounced aversion to treaties. For now, it is one more agreement stricken from the books.

Nor is strategic arms control faring well. For some four decades, starting in the late 1960s, it was at the center of efforts to constrain nuclear capabilities and the negotiating process was a centerpiece of relations between Washington and Moscow. However, apart from a fifteen-month period at the beginning of the Obama administration, during which the New START agreement was negotiated, the strategic arms control process has grown largely dormant and the institutionalized regular dialogue on nuclear issues has disappeared. In contrast to painstakingly negotiated earlier treaties, the 2002 Moscow Treaty was a hastily negotiated two-page document whose contents were so meager and poorly drafted that it called into question the significance of the exercise. The only remaining negotiated constraint on U.S. and Russian nuclear forces, New START (2010), is a serious agreement but it too was in jeopardy. New START expired on February 5, 2021, and during the Trump administration there was no move to negotiate a follow-on agreement. New START includes a provision that allows it to be prolonged for an additional five years, but President Trump was reported to have no interest in extending it and left office without doing so.68 Had Trump been reelected, it is possible, perhaps even likely, that New START would have been allowed to expire. For the Trump administration, that would have represented another significant move in its substantial demolition of what was left of nuclear arms control—bringing to an end nearly half a century of strategic arms control. With the coming of the Biden administration, however, American policy immediately reversed and as one of his first acts in office, Biden agreed with Moscow to extend New START, preserving the existing legal framework for five years and allowing time for negotiating a new agreement. Though the treaty has survived, no one would suggest that strategic arms control is in good health—there is little remaining of the arms control infrastructure that had been built up over several decades, there is no momentum toward a new agreement, virtually nothing remains of the process that produced past agreements, arms control has been discredited in many eyes, and difficult substantive issues crowd the agenda as technologies change and the world grows more complicated. As Nikolai Sokov and William Potter observe, “The fabric of US-Russian nuclear arms reductions is unraveling.”69 The Trump administration has accentuated this trend; it concluded in its Nuclear Posture Review, for example, that arms control is inappropriate in current international conditions and that “further progress is difficult to envision.”70

U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control may be sputtering, but possibly even more striking is the fact that the world’s seven other nuclear arsenals (several of which are growing steadily) are ungoverned by any effective constraining agreement. Meanwhile, on the nonproliferation front, the emergence of three new nuclear-armed states, each working steadily to expand its nuclear arsenal, has undermined confidence in the robustness of the nonproliferation norm. The protracted and never fully resolved crises involving Iran and North Korea have raised criticism of the effectiveness of the NPT regime. Can proliferation really be held back over the long run, when it seems that determined states—with North Korea being the prime example today—can get nuclear weapons if they really want them? How long can the nonproliferation regime keep possible nuclear aspirations at bay? The record of the nuclear age so far suggests that success is possible, but doubters fear the trend cannot last. “Is Nonproliferation Dying?” asked The Washington Quarterly on its cover not long ago.71

In short, far from building on the arms control inheritance of past decades, the arms control frameworks governing nuclear weapons have been discarded, weakened, or jeopardized. The trend toward more extensive constraints and greater cooperation has been substantially reversed, meaning the future nuclear order may be less regulated and more competitive. How much does this matter? Arms control has never been a panacea and has not precluded either geopolitical rivalry or intensely competitive arming. Indeed, skeptics question the net value of the entire arms control enterprise. Brendan Green writes, for example, that strategic arms control “achieved little more than force caps at very high numbers” and dismisses Cold War arms control as “a wildly popular show about nothing.”72 Recognizing the limits of arms control, however, does not erase the difference between a constrained and an unconstrained nuclear environment, nor does it eliminate the contrast between a future rendered more predictable by regulation and the uncertain and potentially more disturbing futures imaginable in an unfettered environment. The notion that a competition bounded by negotiated rules is preferable to a wide open rivalry has lost much of its political and policy force, as reflected in the demise of most of the arms control architecture built up over decades of arduous negotiation. This is another dramatic change in the character of the nuclear order, and moves us back toward the dangerous world experienced in the first decades of the nuclear age.

Technological Advance Undermining Stability?

Worries that nuclear forces might become vulnerable to an opponent’s first strike have been an abiding feature of the nuclear age, notwithstanding the wide belief during the mature Cold War period that large, redundant, protected, or hidden capabilities were sufficient to produce a stable deterrent relationship.73 But now technologies have emerged or are emerging that have the potential to erode, perhaps substantially, whatever stability may be thought to exist. Advances in surveillance, accuracy, lethality, artificial intelligence, and cyber capabilities could make it much more difficult to have confidence in the survivability of deterrent forces.74 The growing transparency of military milieu, for example, could make submarines more vulnerable than in the past, thus undermining a capability that has long been regarded as a survivable guarantor of deterrence. Land-based capabilities (including mobile missiles) may become increasingly vulnerable to attack as improvements in surveillance provide precise real-time targeting information to highly effective attacking forces. Progress across an array of technologies from precision to data processing has increased the potential for making missile defense more effective. Further, technological improvements make it possible to use advanced conventional weapons against strategic targets and nuclear command and control facilities, potentially blurring the line between conventional and nuclear war and possibly creating escalatory risks and pressures in the event of conventional conflict.75 An additional layer of potential threat and vulnerability has emerged with the advance of cyber capabilities, which raise the possibility that command and control systems can be attacked and nuclear operations can be disrupted using cyber assets.76 How far these technological trends will go and how much they will shake confidence in deterrence is still being debated. Nuclear-armed states will be highly motivated to find countermeasures to preserve their deterrent forces. But there can be no doubt that a world of more vulnerable offensive forces, more effective missile defense capable of degrading whatever offensive forces might survive a first strike, more lethal conventional forces capable of use against strategic assets, and larger worries about cyber vulnerabilities will be a more dangerous and less stable world.

In short, over the past two decades, a confluence of multiple trends has transformed the nuclear landscape—and unfortunately, most of these trends have produced new challenges and worries.

Conclusion: New Realities, New Challenges

We live in a new nuclear world—what some are now calling the third nuclear age.77 The nuclear order of 1991 no longer exists. The optimistic and hopeful nuclear ambitions and opportunities envisioned in 1991 never became a reality. As we have seen, starting in the late 1990s there has been a significant deterioration of relations among the great powers, an erosion of arms control, violations of the nonproliferation norm, and the emergence and evolution of potentially destabilizing technologies. The broad storyline, stretching across decades, of evolution from a competitive, unregulated nuclear environment to a more cooperative, regulated environment has come to an end. Instead, as Nina Tannenwald has written, “In this emerging nuclear era, key norms that have underpinned the existing nuclear order—most crucially deterrence, non-use and nonproliferation—are under stress. . . .The global nuclear normative order is unraveling.”78 It is far from clear where this will all lead but it is certain that the old order no longer exists.

As a result, there is a need for what Thomas Schelling described as “strategy in an era of uncertainty.” Schelling, a Nobel laureate in economics and one of the formative strategic thinkers of the nuclear age, has described the difficulty of the task:

Now we are in a different world, a world so much more complex than the world of the East-West Cold War. It took 12 years to begin to comprehend the “stability” issue after 1945, but once we got it we thought we understood it. Now the world is so much changed, so much more complicated, so multivariate, so unpredictable, involving so many nations and cultures and languages in nuclear relationships, many of them asymmetric, that it is even difficult to know how many meanings there are for “strategic stability,” or how many different kinds of such stability there may be among so many different international relationships, or what “stable deterrence” is supposed to deter in a world of proliferated weapons.79

The fundamentally important question is, of course, how can we live safely in such a world? If present trends continue, we may find ourselves living in a future world marked by greater contention among the great powers, more nuclear weapons, more nuclear weapons states, less stability, and less arms control and international regulation of the world’s nuclear affairs. What are the implications of living in such a world? What paths might lead in more constructive directions? How can this more complex environment be most prudently and effectively managed?

Understanding what has changed over the three decades since the end of the Cold War, and debating the implications of those changes, is an essential and necessary step in addressing such questions. In front of us are choices about force modernization, arms control, and technological advancement that will help shape the contours of the evolving nuclear order and that will determine the relative safety or danger of the future nuclear environment. Nuclear matters may have slipped out of the limelight they once occupied and large changes may have gradually occurred without attracting adequate notice, but we cannot avoid seeking to navigate safely what Robert Legvold has described as “the mounting challenges and dangers of a new and far different nuclear world.”80