Principle 2: Communicate Consensus

People are more likely to believe climate change is happening and caused by human beings if they understand that the scientific evidence justifies these conclusions and that there is a scientific consensus about both.

Individuals’ beliefs about climate change are influenced by what they think scientists believe (Lewandowsky, Gignac, and Vaughan 2013). Communicating that there is a scientific consensus about the existence, harmful nature, and need to address climate change can increase acceptance of the existence of human-caused global warming (Bolsen, Leeper, and Shapiro 2014; van der Linden, Leiserowitz, and Maibach 2018). Accepting the scientific consensus about climate change can act as a “gateway belief” to understanding and engaging with other dimensions of the issue (van der Linden et al. 2015). Consensus messaging of this sort works by using perception of widespread acceptance as a means of aligning individual perception with the descriptive norm (for an explanation of the process, see Tankard and Paluck 2017). A meta-analytic examination of the demographic and psychological correlates of belief in climate change found that belief in climate change was stronger among those who accept a source heuristic (“scientists are trustworthy so the scientific orthodoxy must be true”) and a consensus heuristic (“there is scientific consensus around climate change, and consensus implies correctness”) (Hornsey et al. 2016).

The challenge to be addressed:

For decades, the media tendency to imply the existence of two opposed but equally justified scientific positions on the nature, extent, and causes of climate change distorted the public’s perception of the extent of agreement among published climate scientists (Boykoff and Boykoff 2004; Koehler 2016). At the same time, those with a vested interest in sustaining fossil fuel use (Farrell 2016; Supran and Oreskes 2017) were seeding doubts about the extent of scientific agreement (Oreskes and Conway 2011). Worrisomely, a recent meta-analysis concluded that “belief in climate change is more easily weakened than strengthened” (Rode et al. 2021). Consensus uncertainty—a disagreement among experts or about the existence or strength of evidence—is the only kind that erodes a message’s credibility, according to a 2020 review of the literature on the effects of uncertainty in science (Gustafson and Rice 2020).

The climate science:

Since the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “human influence on the Earth’s climate has become unequivocal, increasingly apparent, and widespread, reflected in both the growing scientific literature and in the perception and experiences of people worldwide (high confidence)” (Working Group II 2022).

An analysis of 11,944 climate abstracts from 1991–2011 matching the topics “global climate change” or “global warming” found that, “among abstracts expressing a position on AGW [anthropogenic global warming], 97.1% endorsed the consensus position that humans are causing global warming” (Cook et al. 2013; see also Anderegg et al. 2010).

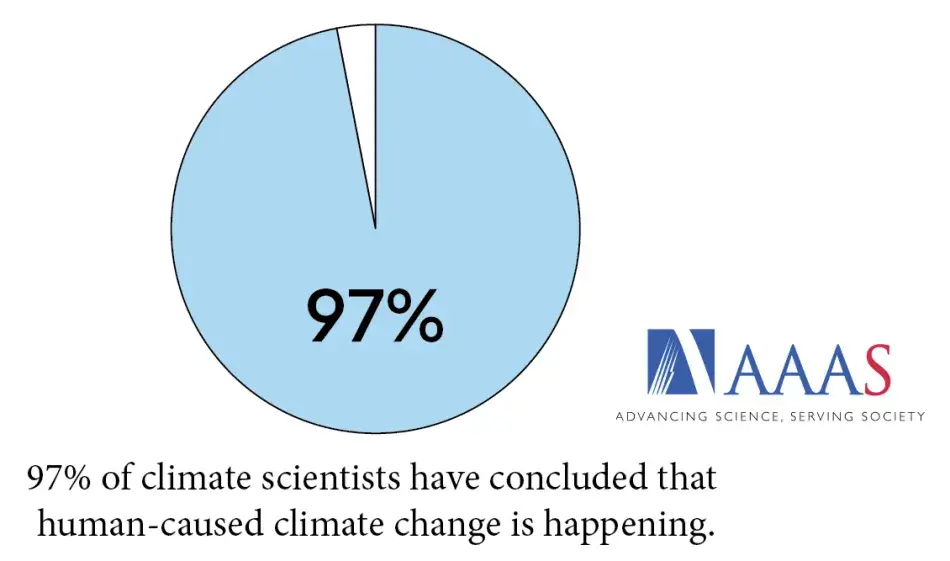

Example 1: Graphically communicating climate consensus

Source: van der Linden et al. 2014.

Effectiveness:

Descriptive text and a pie chart capsulizing the scientific consensus on human-caused climate change (“97% of climate scientists have concluded that human-caused climate change is happening,” with the logo of the American Association for the Advancement of Science [AAAS]) were able to increase belief certainty about estimates of the scientific consensus (van der Linden et al. 2014; see also Goldberg, van der Linden, Ballew, Rosenthal, and Leiserowitz 2019).

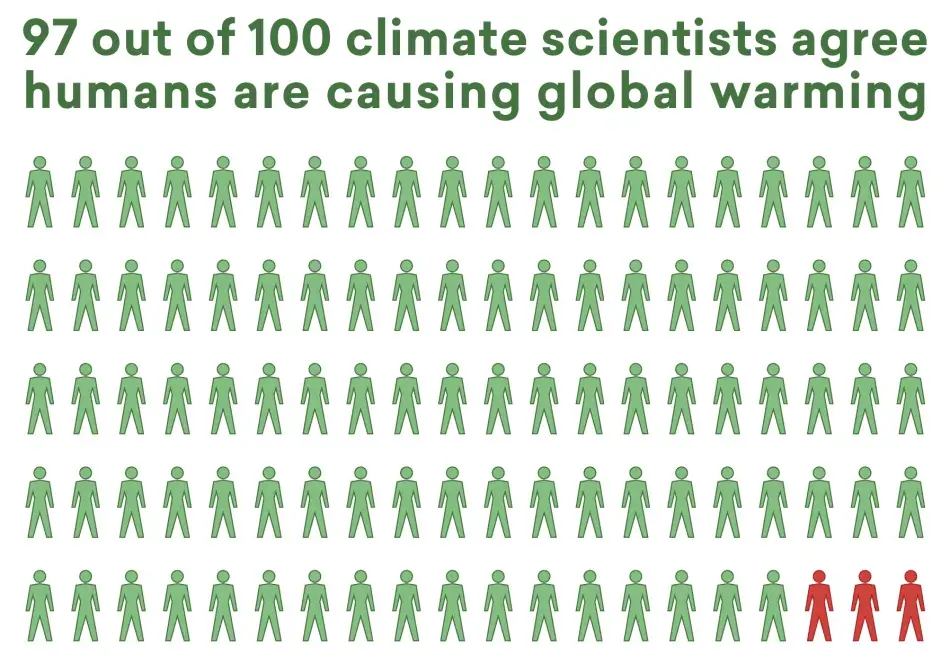

Example 2: Communicating consensus through a pictograph

Source: Cook et al. 2013.

Effectiveness:

By using as a stimulus a graphic that visually represents the percentage of climate scientists who agree that climate change is caused by human activity, Cook and Lewandowsky (2016) found that, although providing consensus information did raise perceptions of consensus, the consensus messaging was potentially polarizing with American subjects who endorse free markets (i.e., hierarchical individualists attributing less expertise to climate scientists). But the consensus information did have a small worldview neutralizing effect on Australians.

Example 3: Dramatizing climate consensus

Source: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver 2014.

Effectiveness:

While climate scientists have generally represented the scientific consensus on climate change using graphs, a segment of HBO’s Last Week Tonight with John Oliver from 2014 has, as of October 2022, drawn more than 8.8 million YouTube views for a dramatization of what the show cast as “a mathematically representative climate change debate.” “It’s a little unwieldy,” host John Oliver said, “but this is the only way we can actually have a representative discussion.” The “overwhelming view of the scientific community” involved a lot of yelling and waving of files, leading Oliver to tell the denier: “I can’t hear you over the weight of scientific evidence” (Last Week Tonight with John Oliver 2014). “If you look at the science,” noted an article in The Atlantic, “rather than just asking people on the street if they believe in global warming, it’s not a 50/50 debate between two sides” (Beck 2014).

On the science podcast Inquiring Minds, science journalist Chris Mooney praised both Oliver’s concision and effectiveness: “I feel like they said in 4 minutes something I’ve been saying for 10 years with like tens or hundreds of thousands of words; what they said was that there’s no debate over global warming, so to have these ‘balanced’ 1-on-1 TV debates is just preposterous” (Nuccitelli 2014).

Effectiveness:

Findings from a randomized experiment showed that viewing the Oliver segment increased viewers’ belief in global warming and perceptions that most scientists believe in its existence (Brewer and McKnight 2017).

Example 4: Communicating consensus through analogy

Source: Science Moms 2021a.

Effectiveness:

Using analogy to convey the scientific consensus, a team of scholars found that belief in human-caused global warming increased as an issue of concern, as did its priority after subjects in a controlled experiment were exposed to either a speaker in the video or print text reading, “If 97% of all dentists told you a tooth couldn’t be saved, you’d pull that tooth. If 97% of all engineers told you your house was unstable, you’d move. And if 97% of all airline workers told you not to get on a plane, you wouldn’t. So, when 97% of the world’s climate science experts tell you our planet is warming and we’re responsible, why would you ignore them? When you’re 97% certain, you’re certain. Protect America from climate change” (Goldberg, van der Linden, Ballew, Rosenthal, Gustafson, Leiserowitz 2019).

The need:

Clear communication that uses trusted messengers to reiterate the scientific consensus that climate change is happening and increasing the likelihood or severity of heat waves, fires, flooding, droughts, and hurricanes.