Principle 7: Make Messages Locally Relevant

Many people in the United States align their identity with groups that have historically doubted climate change. When communicators convey information about a changing climate without attacking these identities, they can convince people more readily. Those who see an issue as local are more likely to be concerned about it and are more likely to support policy solutions to it. Strategies for this include adapting messages to local audiences and communicating through local messengers.

Recent developments in attribution science have allowed climate scientists to show connections between both extreme weather events and local changes and climate change. This is important because the effects of extreme weather experiences on climate attitudes and support for “climate change mitigation responses” have been found to occur among those who attribute the events to climate change (Ogunbode et al. 2019). Trusted local meteorologists are well positioned to communicate such causal connections.

As a person’s perception that climate change is remote and abstract increases, their concern about it decreases. While such perceived psychological distance can undermine climate action, psychological closeness to climate change predicts a heightened level of engagement in pro-environmental behaviors (Wang et al. 2019). By reducing psychological distance, locally framed climate change messages can increase climate change engagement (Scannell and Gifford 2013) and increase perceptions of problem severity and support for local policy action (Wiest, Raymond, and Clawson 2015). By contrast, distantly framed messages that featured victims of climate change backfired among conservatives (Hart and Nisbet 2012). Messages that are personally relevant also are more interesting, more effortlessly processed (Maio and Haddock 2007), and more effective (Kruglanski and Sleeth-Keppler 2007). There is a temporal dimension to psychological distancing as well. Environmental benefits that arrive thirty to forty years into the future are more likely to be discounted than are those in the here and now (Sparkman, Lee, and Macdonald 2021).

The desire to get it right (accuracy motivation) is more likely to come to the fore when a topic is personally relevant and tied to consequences for the individual (Eagly and Chaiken 1993). Direct experience of climate change–related phenomena such as extreme weather events can generate community discussion (Boudet et al. 2020), increase concern about climate change (Bergquist, Nilsson, and Schultz 2019), and elicit “support for mitigation policies, and personal climate adaptation in matters unrelated to the direct experience” (Demski et al. 2017). Weathercasters can increase the salience of those connections.

The challenge to be addressed:

Climate change itself is not directly observable and is seen by some as a psychologically distant issue (far away, not immediate, not affecting the perceiver, and hypothetical) (Liberman and Trope 2008).

U.S. 2022 Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters

This map denotes the approximate location for each of the 15 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters that impacted the United States January – September of 2022.

Source: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information 2022.

The climate science:

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Working Group II 2022 assessment reported that the “increase in global surface temperature [was] 1.09 [0.95 to 1.20] °C in 2011–2020 above 1850–1900. The estimated increase in global surface temperature since AR5 is principally due to further warming since 2003–2012 (+0.19 [0.16 to 0.22] °C). Considering all five illustrative scenarios assessed by WGI, there is at least a greater than 50% likelihood that global warming will reach or exceed 1.5°C in the near‐term, even for the very low greenhouse gas emissions scenario” (Working Group II 2022).

Because of its ability to induce contact dermatitis, the establishment and spread of poison ivy is recognized as a significant public health concern. In the current study, we quantified potential changes in the biomass and urushiol content of poison ivy as a function of incremental changes in global atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (CO2). . . . Overall, these data confirm earlier, field-based reports on the CO2 sensitivity of poison ivy but emphasize its ability to respond to even small (~ 100 µmol mol−1) changes in CO2 above the mid-20th century carbon dioxide baseline and suggest that its rate of spread, its ability to recover from herbivory, and its production of urushiol, may be enhanced in a future, higher CO2 environment (Ziska et al. 2007).

Example 1: Using a credible source to highlight local impact

Known as “South Carolina’s weatherman” (WLTX 2019), Jim Gandy served as News19’s chief meteorologist from 1999 to 2019. In segments titled “Climate Matters,” he harnessed his credibility and identification with the interests and needs of his local community. In an exemplary segment aired in 2016, he showcased research from Duke University, a neighboring institution, confirming that, as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases, so, too, does the prevalence and toxicity of poison ivy.

Effectiveness:

A year-long study of viewers of Gandy’s “Climate Matters” video found that, “after controlling for baseline measures, demographics, and political orientation—viewers of Climate Matters were more likely to hold a range of science-based beliefs about climate change. . . . Climate Matters improved the understanding of climate change among local TV viewers in a manner consistent with the educational content” (Zhao et al. 2014). The effect was not an isolated one. An internet-based randomized controlled experiment involving local TV news viewers (n = 1,200) in Chicago and Miami found that, “Compared to participants who watched weather reports, participants who watched climate reports became significantly more likely to 1) understand that climate change is happening, is human-caused, and is causing harm in their community; 2) feel that climate change is personally relevant and express greater concern about it; and 3) feel that they understand how climate change works and express greater interest in learning more about it” (Feygina et al. 2020).

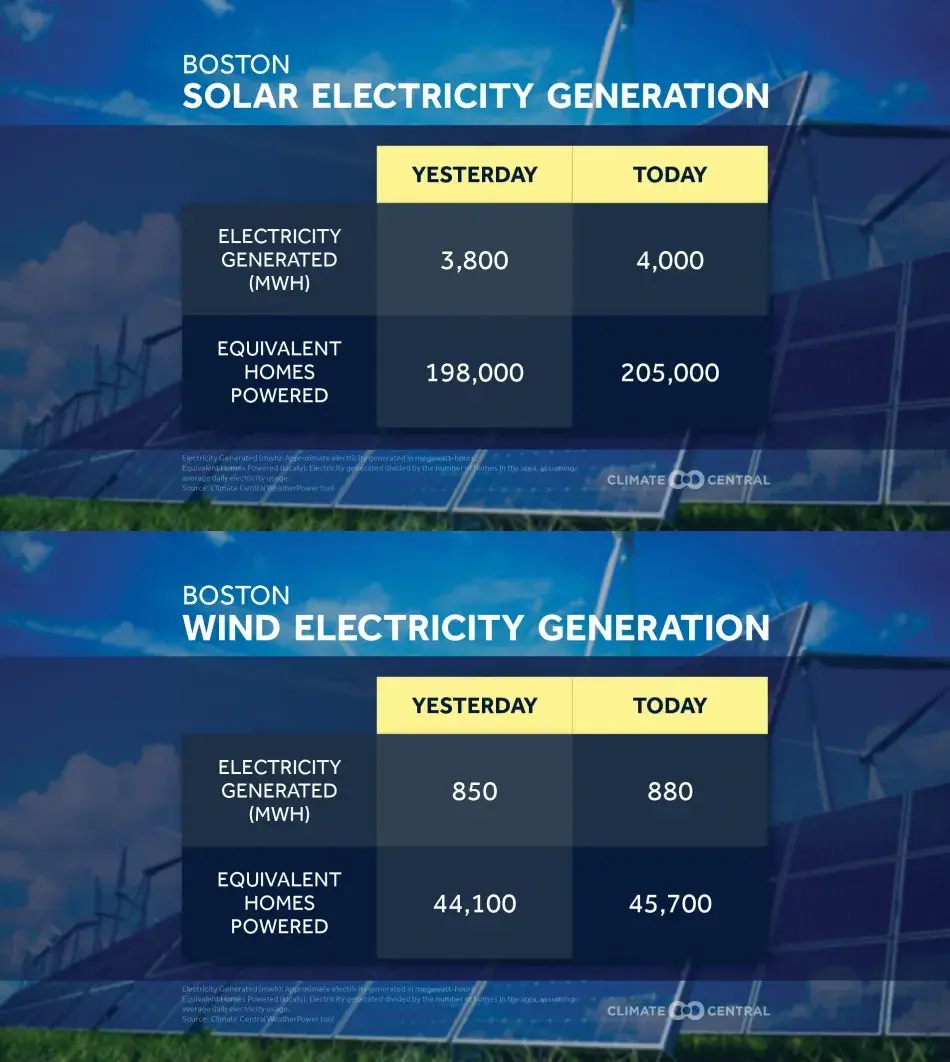

Example 2: Providing tools to help meteorologists localize

The program Climate Matters, which helped create the video in Example 1, has developed a tool for broadcast meteorologists to forecast the wind and solar power generated in a given day and region based on real-time weather data. These forecasts make clean energy solutions both local and concrete.

Source: Climate Central 2022b.

Example 3: Providing broadcast meteorologists with educational resources

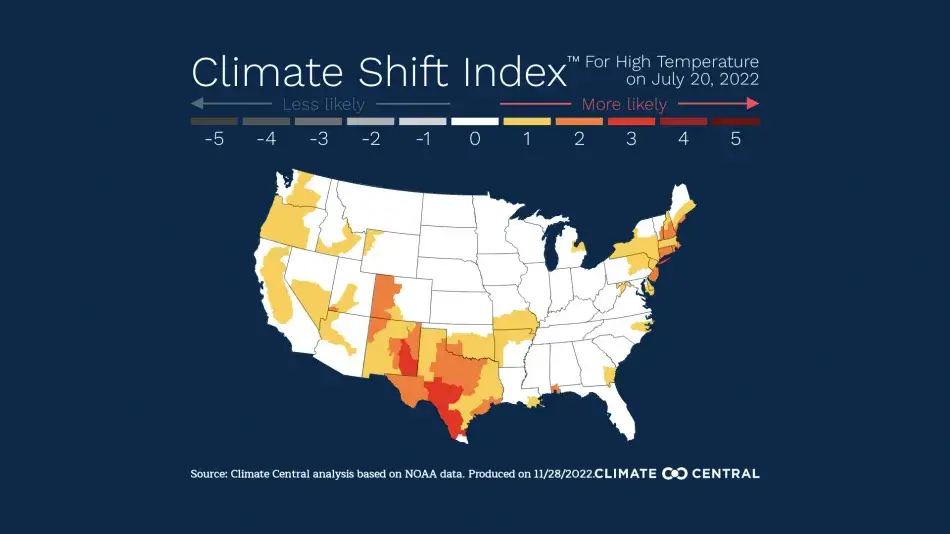

Source: Climate Central 2022a.

Climate Central (2022a) developed a new visualization tool called the Climate Shift Index. According to The Washington Post, the site uses NOAA data to “[show] how everyday weather that may not make news headlines is altered as well . . . [by calculating] how much more likely daytime high and overnight low temperatures are to occur because of climate change. An index score, or CSI, of 2, for example, means climate change made the day’s temperature twice as probable” (Muyskens, Patel, and Ahmed 2022).

Expanding the impact:

Not only is local news personally relevant and locally framed, but it is widely viewed (Pew Research Center 2021) and more highly trusted than its national counterpart (Pew Research Center 2019). Local weathercasters are trusted messengers who regularly provide residents with such usable information as whether to carry an umbrella or bundle up before heading outdoors. In the process, local on-air meteorologists also can educate the public about climate and climate change. A partnership among Climate Matters, Climate Central, the American Meteorological Society, NASA, NOAA, and Yale University provides broadcast meteorologists with training and content designed to increase their impact as climate educators. A 2017 survey of broadcast meteorologists found that about one in four “report longer format science stories on air outside the weather segment” and nearly two-thirds “think the local climate in their area has changed in the past 50 years as a result of climate change” (Maibach et al. 2017). By 2020, “more than 770 weathercasters across 184 media markets [were] participating in Climate Matters, and on-air reporting about climate change ha[d] increased dramatically—approximately 3,200% between 2012 and 2018” (Feygina et al. 2020). According to Edward Maibach (personal communication, April 4, 2022), 2,200 weathercasters are employed in the United States.

“Every meteorologist who is in the business of communicating weather information has an obligation to explain why the weather does what it does, and climate change is playing an ever-increasing role in this story,” argued Jason Samenow (2016), The Washington Post’s weather editor and Capital Weather Gang’s chief meteorologist. “Ignoring climate change in weather reporting is anti-scientific by omission, and it’s irresponsible.”

The need:

Increase the number of meteorologists and other communicators connecting local events to climate change at the local and national levels.