By Victor Lopez, Program Associate for American Institutions, Society, and the Public Good

Across the United States, communities are struggling to reach their economic potential. Big cities and small towns are experiencing population loss and other troubling trends, highlighting an urgent need for revitalization. Reversing these patterns is essential to ensure the entire country benefits from technological and economic progress.

Immigration can be a powerful driver of economic revitalization in the communities where new arrivals settle. However, immigrants often concentrate in a handful of cities, typically places with established communities of people from similar backgrounds. As a result, many areas of the country that could benefit from immigration have yet to see those gains.

These observations informed the work of the Academy’s Commission on Reimagining Our Economy. The Commission calls for shifting the focus from how the economy is doing to how Americans are doing. One of its key recommendations is to address the gap between community need and where immigrants settle. To do this, the Commission proposed the creation of Community Partnership Visas (CPVs), a new immigration pathway designed to bring migrants to areas of the country that could benefit from economic revitalization.

While the Commission outlined some aspects of the Community Partnership Visa program, many details remained unresolved. To address this, the Academy convened an ideologically diverse group of immigration policy experts to refine the case for CPVs and recommend how they should be administered. Academy member Cristina Rodríguez (Yale Law School) leads the working group. (For a list of all working group members click here.)

A key focus of the working group was determining which communities would be eligible to participate in the program. The group concluded that host communities should show a clear need for economic revitalization but should not be facing such severe challenges that visa recipients would have little chance of achieving economic security or opportunity.

The formula to determine eligibility utilizes four metrics:

- Population growth

- Prime age (25–54) labor force participation rate

- Median income growth

- Local cost of living

Communities in the top 80 percentile or the bottom 20 percentile of the first three metrics would be ineligible. These places are already thriving or need a program of economic revitalization beyond the scope of CPVs. Additionally, communities in the top 20 percent by local cost of living would also be ineligible because if these areas are losing population, it is likely driven by housing costs rather than an inability to attract new immigrants.

Because eligibility is tied to the state of the local economy, the working group relied on a unique geographic measure to identify eligible communities. Conventional political units like counties and municipalities are ill-suited for this task. Counties can be too large or sparsely populated, labor markets are not generally confined by county borders, and municipal borders often exclude surrounding rural areas. Therefore, the working group based eligibility on Commuting Zones, namely counties that have been grouped together to capture a single local economy or labor market.

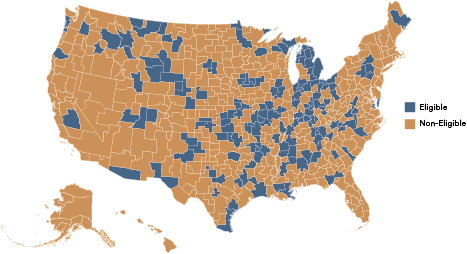

Figure 1. Commuting Zones by CPV Eligibility1

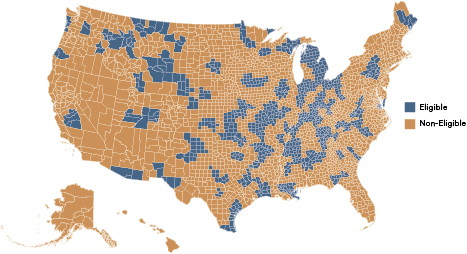

Figure 2. Counties by CPV Eligibility

Figures 1 and 2 show the results of the group’s formula: 30 percent of all counties are eligible, representing 19 percent of the U.S. population, with eligible communities in 39 states.

A key feature of CPVs is their dual opt-in design: both the visa recipient and the host community must apply to participate in the program. While the visas would be issued by a federal agency—the group proposes the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services—local political or economic entities, such as county or city governments or workforce development boards, would apply to participate. These entities are best positioned to determine the needs of their local labor market. For example, does their community need highly educated workers or is it seeking workers in fields that require little or no specialized training? Unlike a similar visa program in Canada, CPV recipients would not need to have a job offer before they arrive. However, participating communities would need to demonstrate that bringing CPV recipients will not displace or harm their local workforce.

The working group’s final report, Community Partnership Visas: How Immigration Can Boost Local Economies, provides a detailed overview of the proposed program. Released in May 2025, the report was launched at an event held at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., featuring Cristina Rodríguez (Yale Law School), Stan Veuger (American Enterprise Institute), Michael Clemens (George Mason University), and Adam Ozimek (Economic Innovation Group).

In the coming months, the working group and Academy staff will conduct outreach to federal and state policymakers to make the case for CPVs. The Academy will also meet with key stakeholders, including members of the business community and workforce-development boards, to identify effective ways to build political momentum for this proposal.

If adopted, the Community Partnership Visa program would provide communities with a powerful new tool to invigorate their economics. Even—or especially—during times of divisive debates over immigration, it is essential that the Academy pursue thoughtful, crosspartisan work. While the outlook for innovative visa programs may seem uncertain now, the nation may soon need fresh proposals to welcome new entrants and support struggling communities. CPVs offer exactly that kind of solution.

Community Partnership Visas Working Group

* indicates an Academy member

Chair

Cristina M. Rodríguez*

Yale Law School

Members

Kristie De Peña

Niskanen Center

Gordon Hanson

Harvard Kennedy School

Douglas Massey*

Princeton University

Cecilia Muñoz*

New America

Gerald Neuman*

Harvard Law School

Pia Orrenius

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

David Oxtoby*

President Emeritus, American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Matthew Slaughter*

Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth College

Stan Veuger

American Enterprise Institute

Tara Watson

Brookings Institution

For more information about Community Partnership Visas and the Commission on Reimagining Our Economy, visit the Academy’s website.