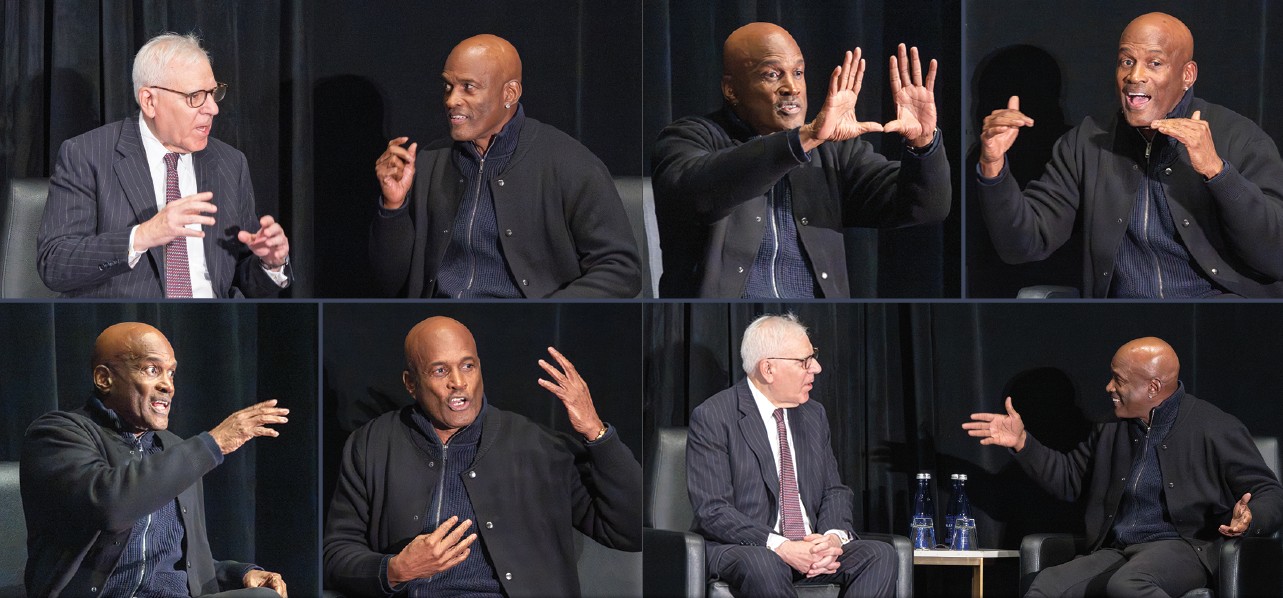

Annual David M. Rubenstein Conversation

2137th Stated Meeting | October 10, 2025 | Cambridge, MA

Induction Weekend 2025 began with an Opening Celebration that featured the announcement of the new Legacy Recognition Honorees with a special message from John Legend, followed by a conversation between David M. Rubenstein, Co-Founder and Co-Chairman of The Carlyle Group, and Kenny Leon, Tony Award–winning stage and television director and new member of the Academy. An edited version of their conversation follows.

David M. Rubenstein

David M. Rubenstein, an investor, philanthropist, interviewer, author, and historian, is Co-Founder and Co-Chairman of The Carlyle Group. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2013 and is a member of the Academy’s Board of Directors and Academy Trust.

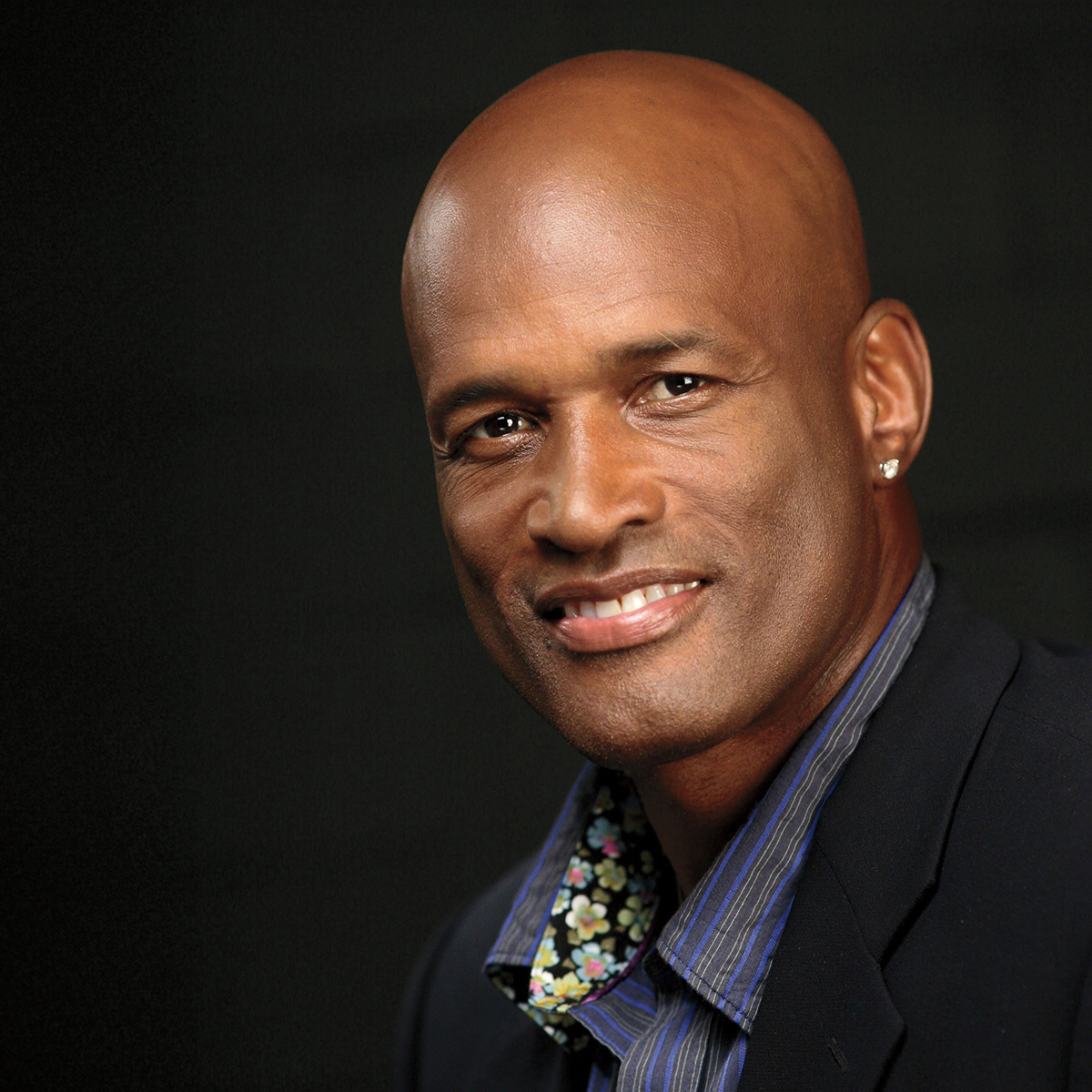

Kenny Leon

Kenny Leon, stage and television director, is the Tony Award–winning Senior Resident Director of Roundabout Theatre Company and Artistic Director Emeritus of True Colors Theatre Company. His work spans from classic theater to drama, comedy, musicals, musical revues, opera, and film. Leon was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2025.

DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN: Thank you very much for interrupting your day today to come here. I understand that earlier today you were working with Tom Hanks.

KENNY LEON: Yes, I was. Before we go any further, I would like to say how wonderful and amazing it is to be in this room with this group of human beings. I see Anna Deavere Smith, the queen of theater, and Bernard Harris, the first Black person to walk in space. Being here this evening has me thinking about August Wilson’s play Gem of the Ocean, when he talks about the City of Bones—about all the Black people that are at the bottom of the ocean, all the kings and queens that are down there. I am excited today because we get to live lives that honor those people at the bottom of the ocean.

RUBENSTEIN: I’m glad you’re happy to be here. Can you tell us a little bit about what you were doing earlier today?

LEON: Sure. Earlier today I was in rehearsal for a new show I’m working on at the Shed in New York. It’s called This World of Tomorrow, and it stars Tom Hanks and Kelli O’Hara. It is a beautiful story about love and time travel.

RUBENSTEIN: When is the show opening?

LEON: It previews on October 30, and runs through December 15. It’s about a guy who lives in 2089, and he goes back to the 1939 World’s Fair and falls in love. The play is focused on the fact that not everything we need is in the future. There are important values in the past. The story asks a question: would you take fourteen years of true love or one hundred fifty years of life without love?

RUBENSTEIN: What’s the answer?

LEON: Man, give me love. Love can change your DNA, and that’s what the play is about. It’s very humorous. Tom Hanks is one of the most fascinating actors I’ve ever worked with, and when I left him today, he said, “Enjoy your train ride!”

RUBENSTEIN: Did he write the play?

LEON: He cowrote the play with Jim Glossman. Earlier someone asked me, Who needs a director? I believe all actors need directors. Actors need somebody who will look at you and tell you what truth is. Most actors do not stand in truth. They stand beside truth, next to truth, around truth, but never in truth. Truth is a scary place. You have to stand in front of an audience and make them disappear. Most actors learn behavior. If I say this line, “Ba-da ba-da ba-da ba-bop-ba-bop bah,” they’ll laugh. If I say, “Ba-da ba-bah ba-bah ba-bah,” they’ll act like they’re crying. But the audience will go home and say, “What the hell was that? I hated that performance.” So we have to go for truth. We’re studying human behavior, and you can’t study human behavior if you’re in your devices. You can’t look at human behavior if you’re on your laptop or your phone. I have a new watch because I wanted to pull myself away from my devices. The only thing I need my watch to do is keep the time.

RUBENSTEIN: Does Tom Hanks need a lot of directing?

LEON: All actors need a lot of directing. I’ve worked with Denzel Washington, Sam Jackson, Phylicia Rashad, and Anna Deavere Smith. Actors give up something to become who they are. If you want my check, you have to take my bills. And a lot of people are not willing to do that. I remember I did Fences on Broadway with Denzel Washington, Viola Davis, and Stephen McKinley Henderson, a great group of people. It was the first day of rehearsal, and we worked for about four hours, and then I said, “Okay, let’s go to lunch.” We’re on 42nd Street in New York, and I get halfway down the stairs, and say, “Where’s Denzel?” Someone shouted back at me, “We’re on 42nd Street. He can’t leave the hall to grab lunch.” So I went back upstairs, and I said, “I’m going to have lunch right here with you.” By the end of that week, every actor in that company was having lunch in the rehearsal hall. We presented Fences on Broadway as a family who broke bread together. It was an amazing opportunity.

RUBENSTEIN: When you’re an actor, what do you most want from a director?

LEON: As an actor, I want a director that I can trust, and I have not always had that. I have a t-shirt that says, “Film is art. Theater is life. Television is furniture.” It’s a joke, but what it means is that in film, you have a camera. You can zoom in on the actors or pull back. You can add music. When you’re onstage in the theater, you’re breathing the same air as the audience. When you’re on television, you can change a lot of things. Film, theater, and television need the director, the actor, and the writer, but the person who gets the last word is different for each. For television, the writer gets the last word. Think of some of the great shows on television: Cheers, West Wing. If the writing isn’t good, it’s not going to work. For stage, it’s the actor who gets the last word. As I mentioned, I’m working with Tom Hanks and Kelli O’Hara. They’re in front of a live audience every night, and if they don’t trust what I say, then they’re going to make subtle adjustments—like I’ll slow this down, or I’ll make this funny. And if the audience is laughing, I’m going to make it funnier to make them laugh more. They start thinking that the audience is the barometer of truth. But that’s not true. The audience is the barometer of what they think they should do right now. For film, the director gets the last word, because you’re in the editing room and if you don’t like something in one scene, you can fix it by taking something from another scene. I can add fake teardrops and put some music under it. Now if I had a choice between which one I’d give my life to, it would be the theater.

RUBENSTEIN: Why do you like theater more than television and film?

LEON: When you’re on a raised stage, in front of the whole community, and you’re breathing that same air, it’s hard to manipulate the truth. Let me give you an example. If you hate profanity and you’re watching a movie and the actor is cursing, you can say, “I didn’t like the movie.” If you hate profanity and you’re seeing a play in the theater, you can say, “My God, why are they cursing? I’m leaving, and we’re canceling our subscription.”

Here’s another example. When you go to the theater and you see blood, it’s “Oh my God!” We tend to run away from that real truth in the theater, and what I try to do as a director is to stay ahead of it. I tell my actors that it’s like a dog following a car. Don’t let the dog catch up with the car. If the audiences catch up with you, and you stop the car, open the door, let the audience in, and then close the door, now the audience is dictating where you go. You’re not surprising them. In theater, surprising moments create great evenings. You have to stay ahead of the audience so they can continue to be surprised.

RUBENSTEIN: When you were notified that you had been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, did you say, “What is the Academy?” or “Why did they take so long to elect me?”

LEON: To be honest, I didn’t know which Academy had elected me. Is it the Academy or another Academy? Jennifer said, “You have to go to the Induction. People have worked hard on your behalf, and it’s a great honor.” But I hate missing rehearsal. And it’s a big deal for me not to be in rehearsal today.

RUBENSTEIN: We are grateful that you are here with us this evening. Let me ask you a few questions. Where were you born?

LEON: Oh, wow. You’re starting at the beginning! I was born in Tallahassee, Florida.

RUBENSTEIN: Did you grow up there?

LEON: Yes. I was the first. My sister was the second, and then came my brother. We had no running water in our house and we had an outhouse. That’s what I grew up with. We had a small farm, and I loved everything about it. My mother left me there when she was a young woman because she had to get away. She didn’t want that life. She left me with my grandmother, which was a great gift for me. I stayed with my grandmother, who raised me. We would sit on the porch in the country and entertain ourselves by waiting for cars to pass by. I would say, “That’s my car. And that’s your car, Grandma. You got that old, raggedy car.” It was a beautiful life. We went to church once a month, because the minister had to go to all the other counties. I grew up in a Southern Christian church. We got baptized in the river behind the church.

RUBENSTEIN: Was it a segregated church?

LEON: We didn’t call it segregated because it had all the people we knew! We did know some white folks because my grandmother took care of a family called the Whites. Growing up, we thought that they were part of our family. We also saw white folks when we went into town.

Let me tell you a story about my grandmother. I found out at the end of my grandmother’s life that she never had Social Security. My grandmother used to send us a dollar for Christmas. A dollar! She had thirteen children and all of them had kids, some of them five, six, seven, eight kids. She sent everybody a dollar. At her funeral, I said, “Grandma, you sent everybody a dollar and you didn’t have Social Security.” Then the preacher said, “I’ll tell you something else about your Grandma. She wanted a cemetery fund, and in the church everybody voted it out, but Mamie put money in the envelope every church service for the cemetery fund.” I got those kinds of lessons from Grandma.

RUBENSTEIN: Where did you go to high school?

LEON: Let’s see, high school. I went to Northeast High School.

RUBENSTEIN: In Atlanta?

LEON: No, in St. Petersburg, Florida. The white folks lived on one side; the Black folks lived on the other side. But when it was time for me to go to high school, the school was integrated. Before then, all the Black students went to Gibbs High School, and we had the best sports team and the best bands. And then they split the Black kids up. By the way, Angela Bassett and I grew up in the same town. We later did a Broadway show together, The Mountaintop. The joy in all that is I got bused to Northeast High School. It was the richest school in the state of Florida. They had modular scheduling, which meant that you go to class for 20-minute mods and then you have free time. But we were away from our homes. So we were like, free time? What are we going to do? The white kids could go home. We could go to the 7-Eleven and shoplift.

The beautiful thing is I made some great white friends, who are friends of mine today. And then I became student council president. I couldn’t be in the plays at the high school. The theater program there would not allow it. They couldn’t see how Black people could be in plays unless you were the butler or the maid. So I led this big protest, and all my white friends joined it. It was a great experience. I learned and grew. When I graduated high school, the last thing I wanted to do was go to a white university, so I went to Clark Atlanta University in Atlanta, one of these beautiful, historically Black colleges. On my first day there, I met Maynard Jackson, who was the first Black mayor. Then I met John Lewis. Then I met Reverend Joseph Lowery. Then I met C. T. Vivian. Then I met Dr. King’s oldest daughter. These people became my friends and my family. I represent that everywhere I go. I grew up on Miccosukee Road, and I ended up on Broadway. I cannot explain that unless there is a God.

RUBENSTEIN: You graduated from college and then went to law school. What were you thinking?

LEON: Growing up in the South, and with a Black community of support, you have to do what you know. If you’re a first generation college student, you’re going to be a minister, a teacher, or maybe a lawyer.

RUBENSTEIN: How long did you last in law school?

LEON: Before I answer let me say a little bit more about when I was in college. I met people like Spike Lee and Samuel L. Jackson. Sam became my best friend, and he’s my best friend today. If you hate Sam Jackson now, you would’ve hated him then. He is exactly the same person. It is not an act. He’s the most consistent person that I know. Sam and I both grew up in the South, and we learned that when you’re eighteen, you either get a job or go into the military. To this day, I love to work. I’m sixty-nine, and I love to work. I had three Broadway plays last year. Sam Jackson probably works more than anybody in film, but that’s what you do. That’s what you give back. And you honor everybody that came before you. In no way could I do this if we didn’t have Lorraine Hansberry and Zora Neale Hurston. David, a quick story?

RUBENSTEIN: Sure.

LEON: Some of the story is partly true.

RUBENSTEIN: Which part?

LEON: The part I say out loud is true. In 1959, what Black story was on Broadway? It was A Raisin in the Sun. That play did not come back to Broadway until 2004, forty-five years later.

RUBENSTEIN: You were the director of the production in 2004, correct?

LEON: I was. Jewell Nemiroff, married to Robert Nemiroff, said that no one can do this play again commercially unless the director is a person of color. So for all those years, there was not an acceptable person of color to direct that play commercially. It’s hard to believe, but that’s what happened. And then in 2004, I directed the play that starred Phylicia Rashad, Audra McDonald, Sanaa Lathan, and Sean Combs.

RUBENSTEIN: What was Sean Combs like then?

LEON: I’m getting there.

RUBENSTEIN: All right, go ahead.

LEON: I contacted all the people who worked on the play in 1959, including the great director Lloyd Richards. As an aside, I love what this Academy is doing with its Legacy Recognition Program. I said, “Lloyd, what I want to do is not the same thing that you did, but I want to honor what you did.” And so we sat and talked. The great Ruby Dee was in the 1959 production. I told Ruby to come by rehearsal and give me notes. Ruby came and most of her notes were about the character of Beneatha. When Lloyd hired her to play Sidney’s wife, she thought she was getting the offer to do Beneatha. Years later, she still liked the role of Beneatha and had a lot of notes.

RUBENSTEIN: You directed A Raisin in the Sun on Broadway twice.

LEON: Yes. Let me say something about Sean Combs. And this is what I say when I talk to graduate students. None of us are going to get out of here alive. So it’s how we treat each other that is important. All we have is our time and talent, and you need to look at life in its entirety. Sean Combs in 2004 was a hard-working person. He built a replica of the set in his Park Avenue apartment so that he could go home and sleep like this poor man. I don’t know what happened later on, but I know when he was working with me, he was working hard.

RUBENSTEIN: Years later, you did the play again.

LEON: Yes. God allowed me another blessing to do that play ten years later, and I did it with Denzel Washington and LaTanya Jackson.

RUBENSTEIN: And you won the Tony.

LEON: Yes, I won the Tony for direction. But the hardest work, and this is why you should not chase awards, was the first time I directed the play. We had an actor, Sean Combs, who never acted before. We had a four-time Tony Award–winning actress. We had Phylicia Rashad coming off The Cosby Show. My job as a director is to see how the entire cast processes information. So from day one I’m saying, I might have to take her to dinner, and I’m not going to say anything to him for a week. We’re trying to get the best from them and uplift them. And I think that’s why actors like working with me because I leave room for them.

RUBENSTEIN: Back to law school for a moment. You dropped out before the end of the first year. So then how did you get into acting?

LEON: I stayed in law school for about six months. And then my brother and my best friend at the time, who passed away last year, were in a serious car accident. I thought they were not going to make it. I was in LA at the time and not liking the city. So I used that moment to leave, to make sure that my buddies were okay. I went back to Atlanta. My mother said I either needed to work or I had to go back to law school. In the newspaper there was a notice for auditions for the Academy of Music and Theater. They would do plays at night, like Richard III and Death of a Salesman, but in the daytime you worked in the prisons, teaching acting to the prisoners. I recruited a group of homeless people to teach the prisoners acting skills, and I put it onstage. I did that in the daytime and then I acted at night, and at the end of the year, I had to decide what I wanted to do. Do I go back to law school, or continue with the acting? At that time, my mother was working as a dietician in a nursing home. She was in a patient’s room and they were watching TV. I had done a commercial where a lady hits me in the stomach. I didn’t have any words but the commercial was funny. My mom says to the patient, “That’s my boy.” And the patient replies, “That’s your son? He can make lots of money.” After that, my mom said acting was okay. So that’s when I made the decision, and that’s how my acting career started.

RUBENSTEIN: You said earlier that you’re sixty-nine years old.

LEON: Yes.

RUBENSTEIN: Too young to be President of the United States.

LEON: I’m thinking about it, though.

RUBENSTEIN: Some people who are turning seventy say that they’re going to slow down. Are you slowing down?

LEON: Not at all.

RUBENSTEIN: In fact, you seem to be speeding up.

LEON: I love what I do. I love telling stories. I love inspiring actors. I love teaching actors. I still have something to give. So for me, working in the arts is life. Thank God my wife allows me to be married to the profession, and I thank her for that.

RUBENSTEIN: You have two children and four grandchildren?

LEON: Yes.

RUBENSTEIN: What do the grandchildren call you?

LEON: Well there’s a story behind that.

RUBENSTEIN: Go ahead.

LEON: There are three girls and one boy, Gabriel. A few years ago I did a play called Soldier’s Play. We won the Tony Award for best revival, and Maria let the kids watch the award show the next day. They are watching the show and my great friend Todd Haimes calls me onstage and says, “This Tony really belongs to Kenny Leon.” The audience leapt to their feet and applauded. Gabriel said, “Those people were standing for you, and he called you Kenny Leon. Can we call you Kenny Leon?” I said, “Absolutely.” So sometimes they call me Kenny Leon and sometimes they call me Opa.

RUBENSTEIN: Would you want any of them to go into acting?

LEON: No. I want them to find their own passion. I think life is finding your passion and figuring out a way to get paid for it. Gabriel is a contrarian. Whatever you say, he’s going to do the opposite. If you say, “You’ll never be an actor,” he’s like, “But I want to be an actor.” He has every instinct of a director, though. He has good visual sensibility.

RUBENSTEIN: What is the key skill to be a good director?

LEON: You have to leave room for everybody else, and you have to have vision. People will ask, why should we follow this person up a hill? I try to give them a reason every day. It’s about trust.

RUBENSTEIN: When you started, it wasn’t easy being an African American actor and director. Is it any easier today?

LEON: It is easier, but we’re in a tricky place now. When I started, I was the only Black director running a major theater in the country. I was running the Alliance Theatre, a $20 million theater in Atlanta. Before me, Lloyd Richards was at Yale Repertory. Now there are five or six people at Arena Stage. And there’s Harlem Stage. So there are more opportunities now. But race is still an issue. We’re still running from race. This generation of actors is disappointed in some things that they think we’re responsible for. And I understand that. It’s like I tell our daughter, “You’re smarter than I am, but I have forty years on you. I’ve got wisdom.” If you get them to appreciate that wisdom, if we open ourselves up as adults to say we don’t know everything, and if we try to look at it through their eyes, there’s a way to bring those things together.

RUBENSTEIN: Who is the greatest actor you’ve ever directed?

LEON: I can name a lot of great actors that I’ve worked with. But let me go back to my last point. Hairspray Live! was one of the best things I’ve ever done, because in that musical there was a ten-year-old, a twenty-year-old, a thirty-year-old, a forty-year-old, a fifty-year-old, a sixty-year-old, and a seventy-year-old in it. If they’re ten, then let them be ten. If she’s twenty, then let her be twenty. There’s something that every decade of life can offer to the whole group. There is nothing better than an eighty-year-old man telling you about life. At the same time, there’s nothing greater than a thirty-year-old who has energy and thinks the world can’t stop them. If we leave room for all of us, that’s a beautiful thing. It’s true in theater and in life. The young folks have always had the fire. In our rehearsal room, it’s a joy and a beauty to be there, because we build truth in the stories that we tell and put onstage. Why would I ever want to retire from that?

RUBENSTEIN: Let me ask you a final question. When you told your children and the people you’re working with that you had been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, what did they say?

LEON: Everybody in my family was touched, perhaps more than I was. And then I started thinking that if I engage with these incredibly smart and talented members of the American Academy, I could learn so much. Yes, I’m sixty-nine, but there’s so much more for me to learn, and so much more for me to give, and so many more stories to tell. I want to learn and I want to grow, because life is for the living.

RUBENSTEIN: Thank you for being with us this evening, and congratulations again on your election to the Academy.

LEON: Thank you.

© 2026 by David M. Rubenstein and Kenny Leon, respectively

To view or listen to the presentation, visit the Academy’s website.