How might social research contribute to a retreat from mass incarceration, make the world fairer, and promote alternatives to punishment that help communities become safer and healthier? In a presentation at the Academy, Bruce Western, Bryce Professor of Sociology and Social Justice and Co-Director of the Justice Lab at Columbia University, explored this topic and the implications of mass incarceration for racial and economic inequality. An edited version of his remarks follows.

2091st Stated Meeting | February 19, 2020 | Cambridge, MA

This afternoon I visited a prison, MCI-Cedar Junction. In 2007, during my first year at Harvard, I taught a course at MCI-Norfolk with a group of Harvard undergraduates and a group from MCI-Norfolk, who were colleges students enrolled through BU’s prison education program. It was an extraordinary seminar and a real turning point for me in many ways. I hope to weave some of that experience into my talk tonight.

My topic this evening takes up a theme I worked on with the Academy ten years ago. In convenings with Glenny Loury, professor of economics at Brown University, we explored the contours of mass incarceration and its implications for racial and economic inequality. Glenn and I edited an issue of Dædalus and contributed to the Academy’s program of work in the area of Democracy and Justice.

Tonight, I want to return to that theme and take up the question of how does social research contribute to the project of justice. How might research help to make the world fairer and, in my area, contribute to a retreat from mass incarceration and promote alternatives to punishment that help communities to be safer and healthier?

This will be a play in three acts. Act One tells the story of mass incarceration, which has been the empirical and policy focus of most of the work I have done in the criminal justice area over the last twenty years. Act Two is about the Boston Reentry Study: a small-scale field study that was more finely tuned to realities on the ground and the immediate questions being raised by policy-makers. And Act Three is about the stories I was hearing in the field, which reflect my rather experimental efforts at a more qualitative approach that aimed to change the narrative around criminal justice reform.

The main thread is that research – particularly in the areas of reducing inequality, and social justice more generally – gains leverage mainly by shifting narratives in public and policy conversations in a way that humanizes, gives voice, and dignifies the social life of those facing oppression, disadvantage, and injustice. Much of the power of our work resides in bearing witness in dark places.

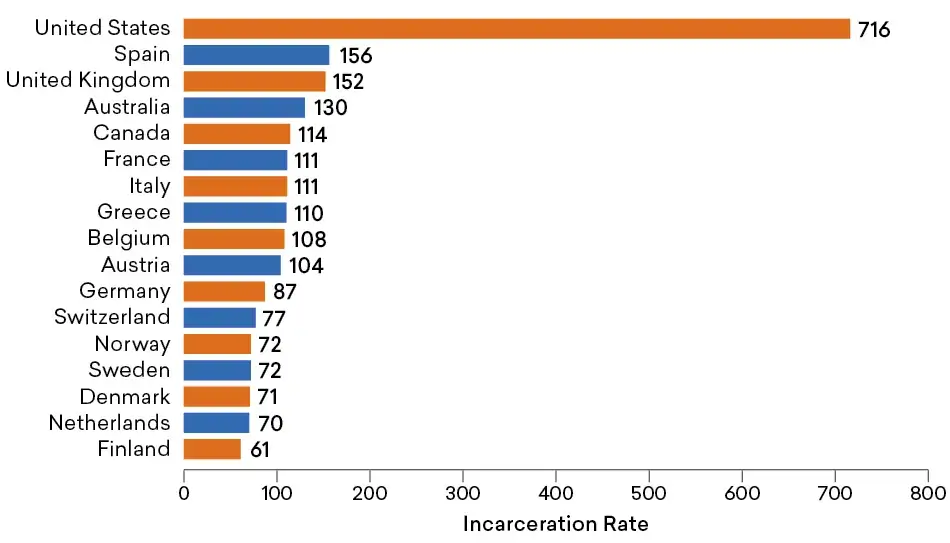

Act One: mass incarceration. We measure the scale of the penal system in a country with an incarceration rate, which is the number of people who are locked up on any given day. This rate is typically measured per hundred thousand of the population. The incarceration rate in Western European countries in 2011 was about 100 per one hundred thousand.

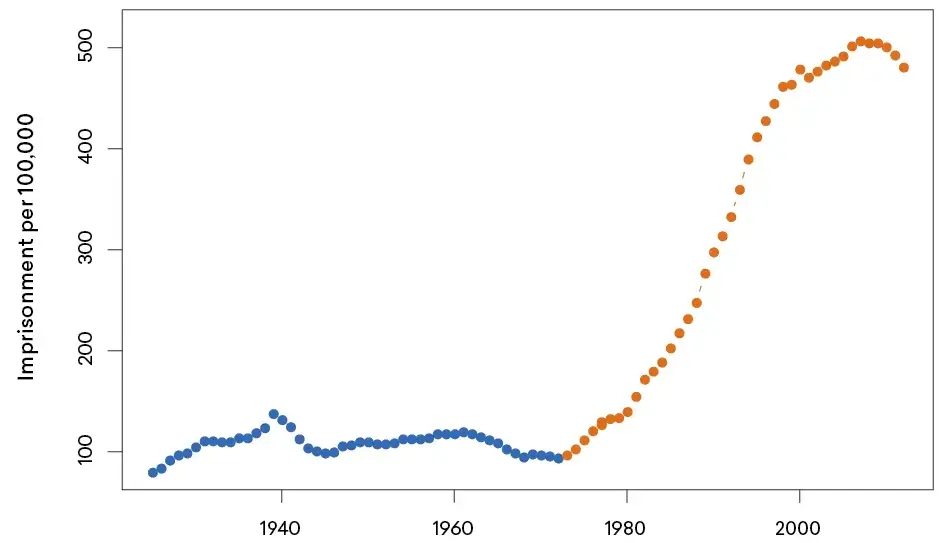

In the United States, the incarceration rate is almost an order of magnitude larger: about 700 per one hundred thousand. Now we can think about how unusual the American penal system is in historical context because we have very good data that go back to the mid-1920s. What we see is that from the mid-1920s to the early 1970s, the imprisonment rate in the United States was around 100 per one hundred thousand – about what it is in Western Europe today. But in the early 1970s the system began to grow. And it grew every year for the next thirty-five years. Over the last ten years it has ticked down a little, but even so, we are still sitting atop this plateau in which the scale of penal confinement in this country is five times higher than its historic average.

Now what does that mean in terms of numbers? By 2013, we had about 1.6 million people in state or federal prison. These are people who were convicted of felony offenses – more serious crimes – and are serving at least twelve months in a state or federal facility. At the median, they are serving about twenty-eight months. Now that is not the entire incarcerated population because there are another 730,000 people in local jails and most of these people are awaiting trial. They are legally innocent but they are incarcerated pending court action, or they are serving short sentences – about one quarter are serving short sentences under twelve months.

But that is not the entire correctional population because there are about 850,000 people in the community who have served custodial sentences and they are meeting with a parole officer out in the community. But that is not the entire community corrections population because another 4 million people have been given non-custodial sentences and they are meeting with a probation officer out in the community. You add it all up and it is about 7 million people in the United States who are currently under some sort of correctional supervision.

Now, as important as these numbers are, what is most important about incarceration in America is its unequal distribution across the population.

Some of the questions we are interested in include: What is the lifetime risk of incarceration? We might be interested in a statistic like that because we think that incarceration confers a whole array of disadvantages that affects you even after you leave prison. How large is the group at risk of those adverse life chances?

Let’s consider a group of men born in the late 1940s. These men are reaching their mid-thirties toward the end of the 1970s, and so they are growing up before the American prison boom.

For African American men in this 1945–1949 birth cohort who never went to college – and that’s about half of all African American men – we estimate that about 12 percent have prison records by the time they are in their thirties. I am talking about the deep end of the system: felony convictions, twenty-eight months of time served at the median. This is work that I have done with my collaborator Becky Pettit, a demographer at the University of Texas at Austin. Becky and I estimated that for African American men who never finished high school and were born just after World War II, 15 percent in this birth cohort would have a prison record by the time they are in their mid-thirties.

Now, consider a birth cohort born in the late 1970s. This is a group of people who are reaching their mid-thirties in 2009. They are growing up through the period of the American prison boom. For non-college African American men, which is about half of all black men, we estimate that 36 percent have been to prison. If they dropped out of high school, we estimate that 70 percent of those black men with very low levels of schooling have been to prison by their mid-thirties.

So within a generation, incarceration has become pervasive for African American men with very low levels of schooling. I should add that this is happening at a time when crime rates are at their lowest level since the 1960s. This is the product of policy change. There was a revolution in criminal justice policy in which prison time became the presumptive sentence for a felony offense.

A whole research program in the social sciences grew up around this stylized fact of pervasive incarceration, particularly in the African American community and particularly among men with low levels of schooling. People looked at labor market outcomes after incarceration. How did formerly incarcerated people do in terms of their employment and earnings? What was the effect of incarceration on their health? What was the effect of incarceration on family life? What was the effect of incarceration on the children of incarcerated parents? Were these effects intergenerational?

The research literature is complicated because there is an enormous amount of non-random selection associated with incarceration. But if I could summarize this literature in a sentence it would be the following: Mass incarceration criminalized a variety of social problems that were related to racial inequality and poverty. Now, some of these social problems included problems of serious violence. But they weren’t limited to problems of serious violence. They also included things like untreated mental illness, untreated addiction, and homelessness. These were all swept up in the American prison boom.

So mass incarceration criminalized social problems related to racial inequality and poverty on a historically unprecedented scale. We have seen evidence of that. And because there were a variety of negative social and economic effects associated with incarceration – such as diminished earnings, diminished employment, family disruption, and diminished well-being of children – mass incarceration tended to contribute to the reproduction of poverty and racial inequality. Incarceration was concentrated among the most disadvantaged segments of the population. Its negative social and economic effects were concentrated there as well. And inequality writ large tended to be reproduced and sustained over the life course, impacting one generation to the next.

A lot of this research was summarized in a National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report. I was fortunate to participate on a panel that worked on this report. I want to acknowledge Robert Sampson, who is in the audience tonight, who was also on that panel. I think it is fair to say that we worked pretty hard on this report. If you are not familiar with the National Academy’s process, a group of scholars are empaneled and they meet together for eighteen to twenty-four months. They work intensively, comb through the scientific literature, arrive at a consensus, and conclude that more research is needed. This is the normal life cycle of a NAS consensus panel report.

As we reviewed the research we were seized with a sense of urgency. And we concluded that given the small crime prevention effects of long prison sentences and the possibly high financial, social, and human costs of incarceration, federal and state policy-makers should revise current criminal justice policies to significantly reduce the rate of incarceration in the United States. So the headline recommendation is this: we have to reduce incarceration rates in America. We are so far out of line with international and historic norms. And the evidence of social damage is enough to warrant a significant policy reversal.

Around the time of the Dædalus issue on mass incarceration in 2010, I was trying to understand the effects of incarceration on labor markets and families. I was crunching away at these big social science data sets. And at that time, I was teaching in prison, and I was hearing lots of stories. And the stories were more complicated than the empirical analysis I was conducting.

I was worried that the work that I was doing on these big social science data sets was not capturing the complexity of people’s lives that were increasingly being revealed to me as I got to know my students and the people in and around the criminal justice system. I worried that I was reducing people to four variables: age, sex, race, and education. And the lives that they were telling me about were much more complicated than that. I knew that the people involved in the criminal justice system were often homeless. They weren’t living in traditional households. And big data social survey methods have a lot of trouble appropriately covering segments of the population that are not living in stable households.

So my data were not fully reflecting the life experiences of people who were caught up in the system. I worried that the kinds of research findings we were generating – negative employment effects, increased family disruption, diminished well-being of children with incarcerated parents – were not sufficiently detailed to tell us what we should do. I remember a meeting in 2010 in which the Obama White House convened scholars working on the impact of incarceration on children. John Hagan from Northwestern ran the meeting. The group working on that problem at the time was relatively small and we were all analyzing the same data: the Fragile Families Data Set, which is a wonderful data set but it is not designed to understand the experiences of people involved in the criminal justice system.

We spent the first half day in Washington talking about all the negative effects of incarceration on kids. There were a lot of Feds at the meeting. A woman from the Department of Education raised her hand and said, “Okay. I’ve listened to all this research for hours now. I’m a teacher in a classroom, and I learn that a student has a parent who is incarcerated. What should I do?” You could hear a pin drop in that room. We had no clue. The kinds of empirical materials we were studying were not providing us with any guidance for that reasonable, very practical, and very urgent question. And that was a warning flag for me. I needed to change something. I was determined to change my methodology, but I’m sure that is not all I needed to change.

Act Two: The Boston Reentry Study. Anthony Braga (at the time he was at the Kennedy School; he is now Dean of the Criminal Justice School at Northeastern) and I were riding the bus back from MCI-Norfolk where we had been teaching a class – our junior tutorial with our Harvard undergrads and the BU students who were incarcerated at Norfolk. I remember saying to Anthony, “I think we have to do a reentry study in Boston. I’m worried that we are not really seeing the full complexity of people’s lives.” But the problem with a reentry study is you cannot keep track of people. The retention rate is 50 percent in most reentry studies because the researchers generally cannot find half of the sample.

Anthony, who knew Boston very well, said, “I reckon I could keep track of everyone.” And so we embarked on the Boston Reentry Study. It was a cohort study conducted in collaboration with Anthony Braga and Rhiana Kohl, my collaborator from the Department of Corrections in Massachusetts. Rhiana runs a research unit at DOC in Massachusetts and she was really an extraordinary partner. We had unbelievable buy-in and access. We went into eighteen prisons in the Massachusetts system: minimum security, maximum security, as well as the state psychiatric hospital at Bridgewater. We interviewed people in offices, in classrooms, and in non-contact units behind plexiglass.

This was a cohort study with 122 men and women. They entered the study a week before their prison release. The only criteria to be eligible for the study was that you needed to be returning to a neighborhood in the Boston area. We asked a lot of questions about employment, housing, health, family relationships, drug use, crime, and contact with the justice system. It is a rich data set, and we are still going through it. A large number of papers have come out of it.

Let me highlight three findings of the study. The first one was unexpected. We interviewed our research subjects over a year, following them in the first year after they are released from prison. We spoke to them one week before prison release, one week after prison release, then two months later, six months later, and finally twelve months later. We had five long interviews over this one-year follow-up period. As we got to know them, they began to share stories about their exposure to violence and other trauma, which often began at a very early age.

Some of the people in our sample were perpetrators of serious violence, and that is why they were incarcerated. A lot of people spoke to us about exposure to violence as victims and as witnesses. The people in our sample had witnessed violence on many occasions – often in their family home at very young ages. So there is very deep trauma in the sample. By the time we got to our exit interviews, we had redesigned our survey instrument to dig more deeply into this question of trauma.

Our second finding is that people coming out of prison are in poor physical and mental health. They have chronic conditions, such as diabetes, and suffer from depression, anxiety, and PTSD. About 15 percent of our sample reported to us that they had a diagnosis of a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder.

Our third finding is that after prison, there is intense poverty and material hardship. The average income in our sample in the year after incarceration was $6,500 – about half the federal poverty threshold for an individual living alone. Poverty researchers call this a level of deep poverty. Insecure housing was ubiquitous. No one in the sample had independent housing in the entire year after prison. This meant that they were doubled up with family, or they were in transitional housing, or in the shelter system, or homeless at some point in the year after their prison release.

What does childhood trauma look like? We asked questions such as did someone in your family have a serious drug problem? Were you beaten by your parents? Have you ever witnessed a death? Forty percent of our sample before their eighteenth birthday had witnessed someone being killed. That is a tremendously high level of exposure to violence as a witness. Parents had lost custody of our respondents in about 40 percent of the cases. Sometimes this meant juvenile justice incarceration in which the state has custody during that time. About 40 percent of our respondents had a family member who was the victim of a serious crime. They also reported domestic violence, depression, and suicidal family members. About 15 percent of our respondents said they were sexually abused as kids.

What about health status? About 60 percent said drugs or alcohol were a problem for them, so there is a very high rate of substance abuse. They also have high rates of depression. There is a lot of chronic pain in the sample, and this was often associated with sustained drug use. Twenty percent reported having anxiety, and about 15 percent said they had a serious mental illness and had reported a psychotic condition.

With this data, we can create an index of childhood trauma. We called these physical and mental health problems “human frailty.” And the interesting thing that we found is that trauma in childhood is positively related to poor physical and mental health in adulthood. That is, people exposed in childhood to the greatest trauma are suffering the most serious health problems as adults. And if they reported to us specifically that they were abused in childhood, they were more likely than not to be in poor health – exceeding even the expectation given their level of trauma in childhood.

Now how is this all related to reentry the year after prison release? If you divide the sample in half between those who were frail, meaning they reported having physical and mental health problems, and those who were not frail, those in the poorest health were most likely to be using cocaine, heroin, or methamphetamine in the year after prison. They were most likely to have very high levels of housing insecurity. They were jobless. Employment improves over the year after prison. We are measuring employment in a very permissive way: meaning any income at all from paid work in the month before the survey. But employment problems are most serious for people in the poorest health. And people with work-limiting disabilities experienced high levels of joblessness.

So the statistics tell one story of the kind of hardship people experience after prison, but the lives of the people we interviewed tell another. I tried to portray many of these stories in a new book entitled Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison.

In the book, I argued that the social world in which mass incarceration lives is characterized by three things: racial inequality, poverty, and violence. Tracing the transition from prison to community there are clear guides for policy here: good reentry policy should provide healthcare, housing, and income support. These are the most urgent needs, and the biggest challenges to social integration after prison.

Politically this is very challenging, because crime politics is deeply racialized and there is also an undeniable reality. The people whom we would like public policy to help have in many cases seriously harmed others. For liberal criminal justice reformers, the issue of violence poses a significant challenge.

[Editor’s note: Bruce Western shows the audience a video clip of one of the respondents from the study talking about violence and incarceration.]

The stories that I hear show how violence is sustained over a lifetime, how prison is itself a source of violence in people’s lives. This raises the question for me whether incarceration on a massive scale can ever be a successful anti-violence strategy.

So we need to ask, if not incarceration, what? The reentry study taught me something about the real conditions of the lives of people who are deeply involved in the criminal justice system. I think the challenge of finding justice involves promoting healing in a family or a community after someone has seriously harmed someone else. This means strengthening the intimate ties of family, friendship, work, and community, and not severing them in the way that incarceration does.

In this vision, public policy is serving a more fundamental purpose. Public policy in the aftermath of violence and other harms involves supporting a very human process of transformation.

[Editor’s note: Bruce Western shows the audience another video clip of a man talking about his son after his son’s brother was shot and killed in a Dorchester neighborhood in Boston.]

The great paradox of mass incarceration is that it demands heroic feats of personal transformation from people whose agency is often compromised by trauma and frailty. I could talk to you a lot more about reentry policies and programs, but at the human level I think we need justice policy to welcome and secure a place for those who have been drawn into violence, whether it is the violence of street crime or the state violence of mass incarceration. This is how a community plays its part in personal transformation.

I want to tell one last story that I hope can provoke our imaginations. I was in Addis Ababa a few years ago for a research project that is studying justice institutions in Ethiopia. I was at dinner with two Ethiopian researchers. One of them, Mulagetta, told me about a colleague, a German anthropologist, at his research institute. One day the anthropologist was out in a remote area driving through a small village. His car tragically struck a small child, killing her. The girl’s parents ran outside to see what happened and a crowd quickly formed around the anthropologist. The parents tended to the child. The anthropologist asked that the police be called, but he was told that there were no police here. The village dealt with matters like this by itself. The anthropologist was told he could go, but they would send for him in a few days. He returned to Addis, and later that week a message came for him that he must return to the village. He was told that he must return alone. He went to my friend Mulagetta and asked what he should do. Mulagetta said, “You have to go back to the village.” So he went back to the village. When he got there he was escorted to a meeting with the elders of the village. First, he was told to pay 2,500 Birr (about $125) to the family of the dead child. Next, he was ordered to buy a goat for the family. He purchased the goat, which was then immediately slaughtered. The father of the dead child was then called to the front of the meeting. The anthropologist, already standing at the front of the room, was told to hold out his hand. He held out his hand, and his wrist was bound to the wrist of the child’s father with the entrails of the goat. The village elder then announced that the anthropologist was now a member of the dead girl’s family. And that was that. He was free to go.

The anthropologist returned to Addis very upset. He felt that he hadn’t properly compensated the family, nor had he been punished. Mulagetta said, “You have to understand, for the rest of your life you are now part of that man’s family. You have all the obligations of a family member. You have to visit from time to time. If they are going through problems, you should help them just as a member of their own family would.”

Western ideas about punishment and retribution were radically absent in this case of customary justice. Like the Ethiopian story, the problem of prisoner reentry raises the question of when does punishment end. When and how are debts extinguished? These questions are as ethical as they are empirical. If research is to help answer these questions, researchers too must take an ethical attitude to their work.

Let me share some concluding thoughts. The world in which the criminal justice system operates lies at the intersection of poverty, racial inequality, and violence. And this world is suffused with moral complexity. Who is a victim? Who is an offender? Who is strong? Who is weak? There are no easy answers to any of these questions. So how do we make judgments? How do we as researchers help inform policy? What is going to heal? What is fair?

The answer, I think, involves two ideas. First, researchers who are interested in this kind of project must be clear and intellectually serious about their value commitments. If we want our research to make a positive difference in the world, we have to be honest and transparent about our value commitments. This is very discomforting for social science. This would have been a very discomforting proposition for me ten years ago. Since Max Weber we have been taught that science as a vocation is a value-free endeavor. After we choose our research questions, values are a source of bias and mark our loss of objectivity.

In the area of criminal justice policy, I have never encountered value-free social science, and I do not believe it exists. So I offer transparency and intellectual seriousness as an alternative. Proclaim your values and elaborate them. If you are studying justice, how could you do otherwise? For those who study the courts, prisons, and the communities that are most heavily incarcerated, two values are fundamental: human dignity and social justice.

Human dignity expresses the imperative of each individual’s humanity – their innate capacity for love and creativity – that is not forfeited no matter their conduct or their punishment. The value of human dignity is expressed, for example, through the Eighth Amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. Social justice says public policy should promote a fair distribution of rights, resources, and opportunities. A criminal justice system that disproportionately punishes communities of color violates the value of social justice.

Second, the work that we do tries to bear witness in dark places. And to do this work in often very challenging settings – solitary confinement units, psychiatric hospitals, maximum security prisons – we have to aim for the highest scientific standards. And often that is a very technical endeavor. Our sampling designs have to be informative. Our instruments have to minimize measurement error. So good science in this setting is no enemy of strong values. And often I think we make the mistake of saying those two things are in tension. Strong values are indispensable to good science.

We should view our empirical work as a test of our values. If prison reentry leaves people homeless without medical care, we are failing the value of human dignity. If the burdens of mass incarceration are concentrated in black communities, we are failing social justice. In my area, for research to serve justice we must confront the real stories of those who have been incarcerated. Our research and its design are important here because they shape what we see and who we hear. We have to go into the field to get proximity. This is a question of research design, but it also has ethical implications. What do we see? Who do we hear? If this work is really bearing witness in dark places, we will be drawn into rich layers of relationships that lie outside the university. We will be one voice among many. And we will offer one kind of expertise among many kinds of expertise. We will learn to speak as readily about our values as our research methods.

Ultimately, I think a project like this should provoke the imagination, much like the Ethiopian story that I shared with you. By testing our values against the real conditions of poverty, racial inequality, and violence that surround mass incarceration I hope that we might ultimately imagine a better path to justice.

© 2020 by Bruce Western

To view or listen to the presentation, visit www.amacad.org/events/criminal-justice-social-justice.