The American public holds the humanities in high regard, and most people engage in one or more humanistic activities at work and in their leisure hours, according to a recent national survey by the Academy’s Humanities Indicators project (available at https://bit.ly/HumSurvey). The survey, conducted with generous funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, asked 5,015 Americans age eighteen and older who participate in NORC at the University of Chicago’s nationally representative AmeriSpeak Panel about their engagement in a variety of humanistic activities, as well as their beliefs about the personal, societal, and economic benefits of the humanities.

While many in the field will find positive takeaways from the survey, asking the public directly about “the humanities” as a concept proves quite challenging. Preliminary testing for the survey found that some Americans connect the term to activities and notions that have little relation to the field (such as “giving blood” or science, “since that is about humans, right?”). To address that concern, and in keeping with the Indicators’ understanding of the field, the survey was structured to ask first about the what and where of engagement in humanistic activities without ever employing the term. It was only at the end that the survey pointed respondents back to the earlier practices to introduce the term humanities and underlined the definition as “studying or participating in activities related to literature, languages, history, and philosophy.” Only then were respondents asked about their opinions of the field.

Engaging with the Humanities in Everyday Life

The ambiguous understanding of the field among Americans also extended to their daily activities: the survey found very few Americans engage in a wide range of humanistic activities, or even showed much tendency to engage in activities related to a specific discipline. For instance, adults who watch history shows were not much more likely to research history subjects online than other Americans. Instead, the engagements tended to cluster by mode of activities, as readers of fiction were more likely also to be readers of nonfiction, people who watched history shows were also more likely to watch shows on other humanities subjects. So, while humanities insiders often treat the field as a unified concept, that is not how it is experienced by most Americans.

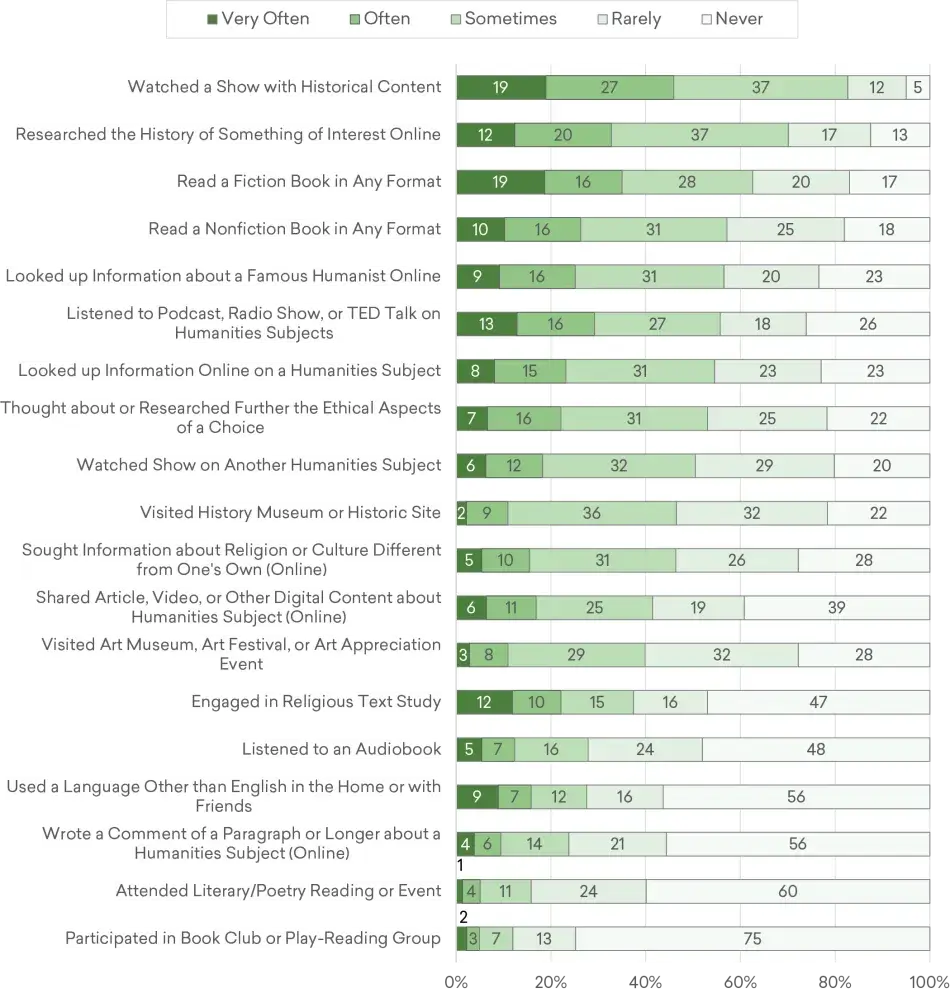

While the mix of activities appears rather eclectic from a content perspective, the survey did find that almost all Americans (97 percent) occasionally engage in one or more of these activities. What is also notable is that while reading is often depicted as the most fundamental of humanistic activities, watching shows with historical content proved to be the most popular form of humanities engagement (see Figure 1). Forty-six percent of adults watched such shows often or very often in the previous twelve months. In comparison, 35 percent read fiction and 26 percent read nonfiction at a similar rate. The humanities activities with the lowest levels of engagement generally had a social, travel, or cost component, such as sharing humanities content online, or going out to museums and historic sites. For instance, 60 percent of Americans rarely or never visited an art museum or attended an art festival or art appreciation event.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Similar to the engagement in leisure activities, the survey found most Americans use humanistic skills and practices in the workplace. Of seven skill areas included in the survey (ranging from reading and writing to working across cultural differences and using a language other than English), Americans used an average of four of them at least sometimes in the work-place, and 81 percent often used at least one of these skills in their jobs. More than half of Americans reported they worked with people from different cultures often or very often as part of their work, and about as many engaged in descriptive writing. And for almost every skill included in the survey, roughly one in four Americans believed a deficiency had hampered them in their job.

Engagement with the various humanities skills and activities in both the home and at work were strongly associated with income and education. Americans with either college educations or in the top income brackets were significantly more likely to make use of the humanities in their lives. Curiously, however, college graduates in engineering and computer sciences were among the least likely to engage in humanities activities in their private lives, but they appeared to be among the most likely to use humanistic skills at work, such as writing.

Attitudes about the Humanities

Despite the differences in engagement with the humanities, the survey found that once the concept of the humanities has been explained, most Americans hold favorable views of the humanities and the potential benefits of the field.

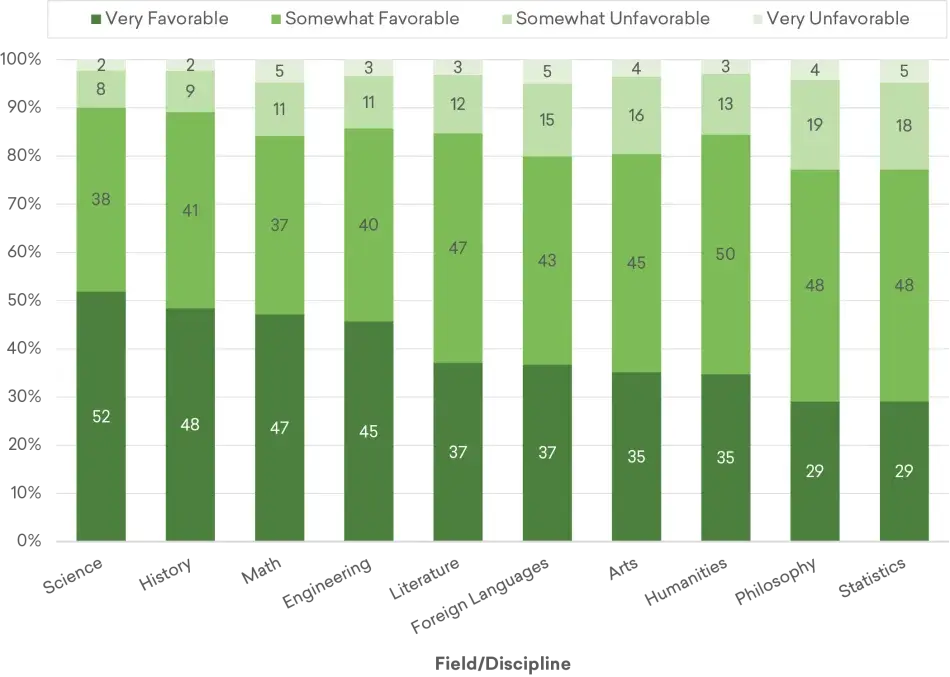

For example, the share of Americans who had a favorable reaction to the term humanities was similar to the response for science, engineering, and math, as 84–90 percent viewed all of them at least somewhat favorably (see Figure 2). However, science, engineering, and math were substantially more likely than humanities to be viewed very favorably. While 35 percent of Americans had a very favorable impression of humanities, science was viewed very favorably by more than half of Americans, and engineering and math were viewed very favorably by approximately 46 percent of Americans. In most cases, the public responded as favorably, if not more so, to particular humanities disciplines than to the broader field. Notably, history was especially popular, with 48 percent of Americans viewing it very favorably, similar to the share for science (52 percent).

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the survey also found notable divisions between college graduates from the humanities and the STEM fields. Almost 70 percent of humanities majors had a very favorable impression of the humanities, while only 28 percent of engineering and computer science graduates held a similar view. Conversely, less than half of humanities graduates had a very favorable impression of engineering and computer science. And while 63 percent of humanities majors were very favorably disposed toward science, that percentage was smaller than the share of graduates from the natural sciences who held that view.

While the response to the term humanities was somewhat ambivalent, more than 80 percent of American adults agreed with an array of positive statements about the field. First among these was the statement that “the humanities should be an important part of every American’s education,” with 56 percent of Americans agreeing strongly and another 38 percent agreeing somewhat. And with one notable exception, at least 60 percent of Americans disagreed with a corresponding set of negative statements about the humanities. The exception was the observation that “the humanities attract people who are somewhat elitist or pretentious.” While only 12 percent of adults strongly agreed with this sentiment, another 39 percent agreed somewhat.

The Humanities in Education

Even before the recent challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic, many in the field had been expressing growing alarm about the decline in college majors and enrollments. While the survey did not ask specifically about the choices that might be causing those declines, it did ask when, where, and what people value in humanities education. For instance, the study found that 78 percent of Americans wished they had taken more courses in at least one humanities subject during their studies, with languages other than English garnering the most interest. Given a range of humanities and nonhumanities subjects to choose from (and allowed to select more than one), almost half of Americans (49 percent) chose languages, followed by computer science (45 percent), social and behavioral sciences (40 percent), and business (39 percent; see Figure 3). History was the second most popular among humanities subjects (with about a third of adults wishing they had taken more courses in either American or world history, and 42 percent wishing they had taken more history courses). More than 20 percent of adults wished they had taken more classes in philosophy, ethnic studies, literature, and art history/art appreciation.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

For most of the humanities school subjects included in the survey, at least 80 percent of Americans felt that teaching these subjects to children was important or very important. But when it came to teaching young people languages other than English, differences in religious thought, and art history/art appreciation, substantially smaller shares of Americans were as supportive. Once again, education level played a substantial role in American attitudes. Adults with college degrees were more likely than those with a high school diploma or less education to affirm the importance of teaching young people the humanities subjects mentioned in the survey.

Given the scale and cost of the survey, it is unclear whether the Humanities Indicators will be able to undertake a similar study in the future. This was the first national survey that explored broadly the humanities in American life; the only previous survey, which asked just a single question specifically about the humanities, was conducted in the early 1990s. But the Humanities Indicators project will continue to track data and report on the health of the field (at www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators) and seek other opportunities to explore public attitudes about the humanities.

For questions about the findings from the Survey of the Humanities in American Life, ideas for another iteration of the survey, or general inquiries about the data, please contact Robert Townsend, codirector of the Humanities Indicators, at rtownsend@amacad.org.