2109th Stated Meeting | October 3, 2022 | In-Person Event, American Academy of Arts and Sciences | Morton L. Mandel Conversation

In 2021, the Academy launched the Commission on Reimagining Our Economy (CORE) to rethink the values, policies, narratives, and metrics that shape the nation’s political economy. Rather than focus on how the economy is doing, the Commission seeks to direct a focus onto how Americans are doing, elevating the human stakes of our economic and political systems. But what does a reimagined political economy look like? What should be the role of government, markets, and civil society in fostering well-being? The Academy convened a distinguished panel of experts – U.S. Representative Jim Himes, Chair of the House Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth; U.S. Representative Bryan Steil, Ranking Member of the House Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth; Justice Goodwin H. Liu of the California Supreme Court; CORE cochair Ann Fudge; and Academy President David W. Oxtoby as moderator – to explore how a reimagined economy could enable opportunity, help communities that have been left behind, and cultivate a healthier democracy. An edited version of the panelists’ remarks follows.

David W. Oxtoby is President of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was elected to the Academy in 2012.

Good evening and welcome. As President of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, it is my pleasure to formally call to order the 2109th Stated Meeting of the Academy. I would like to begin by acknowledging that today’s event is taking place on the traditional and ancestral land of the Massachussett, the original inhabitants of what is now known as Boston and Cambridge. We pay respect to the people of the Massachussett Tribe, past and present, and honor the land itself, which remains sacred to the Massachussett people.

This event has the distinction of being a Morton L. Mandel Conversation, made possible by the generosity of the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Foundation. Morton Mandel was an Academy member who understood the necessity of connection and dialogue when addressing the world’s challenges. We are grateful to the Mandel Foundation for this opportunity to come together for tonight’s conversation on Reimagining the American Economy.

Earlier today, we convened a meeting of the Academy’s interdisciplinary and cross-partisan Commission on Reimagining Our Economy. The Academy launched this Commission out of a concern that the state of the economy was having an adverse effect on Americans’ well-being and the health of our institutions. The Commission has made great progress to date rethinking the values, policies, narratives, and metrics that shape our nation’s political economy.

This evening we are excited to continue this conversation and to welcome local Academy members and guests who can contribute their own distinct perspectives on the challenges facing the nation’s political and economic systems.

The Academy is committed to strengthening the impact that our work has on the world. As part of that effort, we seek opportunities to build connections with policy-makers and to host collaborative conversations with elected officials from around the country. Tonight, we have the pleasure of hearing from the leadership of the United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth. Congressman Jim Himes represents Connecticut’s Fourth District in the United States House of Representatives and serves as the Chair of the Select Committee. In addition to his work on the economy, Congressman Himes serves on the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. We are also pleased to have Congressman Bryan Steil, who represents Wisconsin’s First Congressional District in the United States House of Representatives, and is the Ranking Member of the Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth. Congressman Steil also serves on the House Financial Services Committee and is a co-founder of the Congressional Future of Work Caucus. We are grateful to Representatives Himes and Steil for joining us today, and for lending their time and expertise to this important topic.

We are also pleased to be joined by the Honorable Goodwin Liu, Associate Justice of the California Supreme Court. Justice Liu was previously professor of law and Associate Dean at the UC Berkeley School of Law. He was elected to the Academy in 2019 and serves on the Academy’s Board of Directors and on the Academy’s Trust, and is a member of the Academy’s Commission on Reimagining Our Economy.

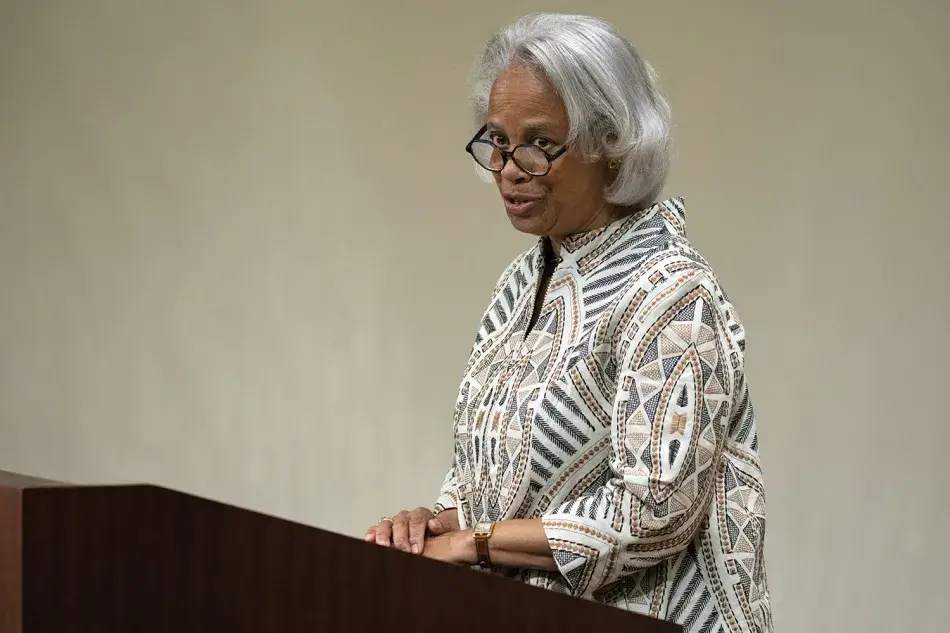

It is also my pleasure to introduce Academy member and Cochair of the Commission on Reimagining Our Economy, Ann Fudge. Ann is the former Chairperson and CEO of Young & Rubicam Brands, as well as a committed philanthropist and civic leader. She currently serves on the boards of Northrop Grumman and Novartis, and is Chair of the Board of WGBH Public Media. Ann was elected to the Academy in 2019, and is a member of the Academy’s Trust. Ann will provide a brief introduction to the work of the Commission, and then our conversation will follow.

Ann Fudge is the former Chairperson and CEO of Young & Rubicam Brands. She was elected to the Academy is 2019, is a member of the Academy’s Trust, and is a cochair of the Academy’s Commission on Reimagining Our Economy.

Good evening, everyone. Thank you for joining us. In October 2021, the American Academy launched the Commission on Reimagining Our Economy with the goal of elevating the human stakes of our economic and political systems. Too often there is a focus on how the economy is doing, and we wanted to direct a focus on how Americans are doing. Our interdisciplinary and cross-partisan Commission includes scholars, journalists, artists, and leaders from the faith, labor, business, and philanthropic communities. Our work is built on the idea that well-being is not simply a matter of dollars and cents but is based on the degree to which people feel their voice is valued, that they think the rules are fair, and that they can trust their leaders and their neighbors.

The impact of economic challenges in the United States has broad implications. The belief that the economy does not give everyone a fair chance literally threatens the nation’s social fabric and its constitutional democracy. The Commission’s meeting earlier today marks the end of a year-long fact-finding phase. We have been holding listening sessions with Americans across the country to hear from voices that have typically been excluded from conversations around economic policy, and we have been working on developing a new set of metrics to reimagine how we measure well-being. We hope to release our final report next year, followed by a sustained period of outreach and implementation.

I look forward to our conversation this evening about some of the most pressing challenges facing the nation. I would like to thank Chairman Himes and Ranking Member Steil for coming to Cambridge and meeting with the Commission this afternoon.

OXTOBY: Thank you, Ann, for that overview and for your invaluable leadership of this Commission. Let me start with a question for Chairman Himes and Ranking Member Steil. Would you briefly explain the mission of the Select Committee, and why each of you personally wanted to take a leadership position in these efforts?

Jim Himes is serving his seventh term representing Connecticut’s Fourth District in the United States House of Representatives. He is the Chair of the House Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth; Chair of the Subcommittee on National Security, International Development and Monetary Policy of the House Financial Services Committee; and a member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence.

I would like to thank the Academy for inviting me to join this conversation. I have been in town all day and have appreciated the opportunity to learn from the members of the Academy’s Commission on Reimagining Our Economy.

The mission of the Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth is fairly straightforward; it is to look at the difference between the most fortunate and least fortunate Americans in this country – a difference that is as intense now as it has ever been in our history – to think about why that is true today, and to propose policy solutions to address it. Our politics are broken because we are in an immensely polarized moment right now. Bryan and I are working hard to try to demonstrate that there is an opportunity to address this important problem in a civil way.

As to why I sought the chairmanship of this Committee, there is a short and honest answer to that question: Speaker Pelosi asked me to, and you don’t say no to Speaker Pelosi! But let me give a more interesting answer. I think the work of this Committee is important for at least two reasons. One, the moral-ethical reasons. I subscribe to what the Conference of Catholic Bishops said in the 1960s, that great wealth is a sin in the context of great poverty. And that is where we are trending in this country now. Two, the economic reasons. The economists in the room are the experts, but I believe substantial disparity leads to reduced aggregate production. What is interesting to me and what really engages me is that at the core of our broken politics is the sense that more Americans than ever before feel that they do not have the chance to live the American dream, that they do not have a stake in the system. And Americans who feel that way are going to seek out radical and extreme political answers. We see that happening right now.

OXTOBY: Thank you. Congressman Steil?

Bryan Steil represents Wisconsin’s First Congressional District in the United States House of Representatives. First elected in 2018, and now in his second term, he was appointed as the Ranking Member of the House Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth. He also serves as the Ranking Member of the Subcommittee on Elections for the Committee on House Administration and is a member of the House Financial Services Committee.

Thank you for the opportunity to participate in this program. I think the economy is far too often overlooked in our national dialogue. We want to make sure that people can sustainably move into the middle class, but the most disadvantaged among us are seldom able to do this. It is not simply a math problem that says that poverty can be solved by a simple wealth transfer. That process does not sustainably allow people to enter the middle class and to be able to chart their own course in the long term. So, the policy objective is to make sure that we are leveraging the American capitalist structure to allow people to enter the middle class and move forward.

We have experienced challenging years because of the pandemic, and during the past two years we have seen the crises worsen. We have an opportunity to find those areas of common ground and to say here are the policies that can substantively and meaningfully help people to move ahead, policies that we can put forward in Washington that can improve our country.

OXTOBY: Thank you. Justice Liu, let me turn to you. Ann offered some background on the Commission, and the Chairman and Ranking Member provided some motivations for their work. What is the problem facing the nation that inspired you to join the Academy’s Commission?

Goodwin H. Liu is an Associate Justice of the California Supreme Court. He was elected to the Academy in 2019, is a member of the Academy’s Board of Directors, a member of the Academy’s Trust, and a member of the Academy’s Commission on Reimagining Our Economy.

It is an honor to be on the stage with the Chairman and the Ranking Member of the Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth, which has done tremendous work already. I encourage you to go to the website and look at all the things that are going on in this Committee.

I wear several hats. Tonight I will speak as a Commission member who has had the benefit of listening. In my work as a judge, we see these issues, though not in a direct way. We see the consequences of economic inequality in terms of who has access to the courts and the gap between rights on paper and rights in practice. But let me hearken back even further. Before I became a judge, I was a law professor and an avid student of education policy. But maybe the easiest way to answer your question, David, is through a more personal lens. I grew up in this country as a child of immigrants; my parents came to the United States in the late 1960s. My mom said that she came with $500 in her pocket – not to spend, but for the return ticket home in case things did not work out.

I was born in Augusta, Georgia, which is a far distance from here. And I grew up in a very small town in the southern part of Florida before finally moving to Sacramento, which I consider my hometown. My parents were family practice doctors. They never made a fortune, but they lived perfectly good lives and were able to provide a very decent life for my brother and me. We never wanted for anything. Most importantly, we had great public schools, and this was toward the end of the time when California had the best schools in the country; now they are often ranked in the bottom third of the country. Needing to get a private education or have an alternative to get ahead in life was a remote concept. There was no thought that you couldn’t just rely on the basic surroundings that you had to have the economic stability and the resources to live decently and get ahead.

My parents exemplify what it meant to work hard, play by the rules, and be rewarded. Now as a parent myself with a teenager and a soon-to-be teenager, I think the ground rules look very different. I have a child in private school. I wonder about the opportunities that are afforded people who do not have the privileges that my family has. I can see the difference between my own upbringing and the more unequal society my children inherit today. And that more than anything is why I felt compelled to be a part of this Commission.

OXTOBY: Thank you. Now let me ask a question to all of you. One of the things that we have talked about is listening to American voices. This has been a major part of the work of the Academy’s Commission. We have had thirty-some listening sessions around the country, and the Select Committee has had quite a few listening sessions as well, listening to Americans who are not always included in conversations about the future of the country. I am curious about what your experience has been with these conversations, and what you have learned from them that we might not learn from other sources. I will start with Representative Himes and Representative Steil, and then turn to a few members of the Commission.

HIMES: If you serve on a congressional committee, the danger is that you will never leave the twenty square miles of the District of Columbia. And so early on, we made a commitment to spend a lot of our time outside of Washington. And, in fact, we kicked this off two years ago with a visit to Lorain, Ohio, an old steel town. Part of the point was to highlight the voices of people. When you are in Congress, it is tempting to listen to the voices from the Brookings Institution or from the American Enterprise Institute. In our report, we will feature stories as a way to differentiate our report from other congressional reports. We know that stories are far more powerful at moving people than policy arguments, and so we will feature those stories. We are also working on a documentary that will highlight people because we want to offer not only policy recommendations but to share a product that we hope will create some empathy that Americans might feel for each other. There is a real deficit of that in the country today.

We are asked by social media and our politics to regard the other as the other, as the enemy, as the person who is wrong. For us, it is as much about learning, and this is probably true of people at the top of their professions regardless of the profession. When you stop listening, you stop observing. One of the problems in the country now is the disconnect between what happens in Washington and what happens in Lorain, Ohio, or at the Texas border. I think my friend Bryan would agree that when you are out in the world, you see that the world is much more complex, rich, and less subject to simple political shibboleths than you do when you are sitting and arguing in Washington.

STEIL: Chairman Himes has done a great job by bringing us out of Washington, D.C., and taking us across the country – from Seattle, Washington; to Kenosha, Wisconsin, near my home; to Lorain, Ohio. I think there are two things that are playing out here. First, there are a lot of Americans who do not feel that they get a fair shake in the economy – people on the political left, people on the political right, and people who do not fit anywhere on the scale – and engaging in dialogue with these people as to why they feel that way is important as we craft and create policies to allow the economy to work for everyone. Second, as Chairman Himes referenced, by going out and speaking to people, you are forced to see how these policies play out in the real world. It is one thing to have an academic conversation about how government transfers wealth, about how different programs have worked, but it is another to speak to people outside of Washington and to listen to them.

OXTOBY: We have a few people in the audience who have some experience going around the country and asking people about their experience in the economy. Jim Fallows, could you say a little bit about what you have done, and pose a question if you wish to the group?

JIM FALLOWS: It has been a privilege to be part of this Commission and to have the two members of the Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth join us at our Commission meeting this afternoon. What the Select Committee and its members are doing is extremely valuable.

What has impressed me among the many things in the Commission’s work are the listening sessions, which is the working group that I participate in: hearing the sophistication of Americans talking about their own predicament. You realize when you talk to people about their situation in life that they are not stereotyped in having the kind of polarized answers you hear on cable news. People are smart when you ask them about their own situation. They know what their responsibility is; they know the things that are open to them, or maybe stacked against them.

I think there is great potential for bipartisan agreement on ways to make the American economy seem fairer for more people because you can work around the normal political divides – when people sense that there should be more opportunity for more Americans to play by what most people recognize as being the rules of the game and have better futures for themselves and their family. I think there is natural overlap and complementarity between what you all are doing in Congress and what the American Academy’s Commission is trying to do.

HIMES: If you spend time with Bryan and me, you will hear a civil and maybe even unusually thoughtful treatment. That is not an accident, and it is no credit to us. It is because both of us represent purple districts, so we have the luxury and the room to do that. The problem with the kind of nuance that Jim Fallows talks about is that it is not in anyone’s interest to see the world that way. It is certainly not in social media’s interest, where what grabs attention is rage and anger. I am far from an expert on this, but anger and rage drive engagement.

In the political world, the most powerful story is the human story: good versus evil. The moment you get into the nuance that lives out in the real world, you are in a place that is profoundly uncomfortable if there is a zero-sum game between the two parties. There are a lot of reasons why this is different from how it was fifty or one hundred years ago. You don’t win if you move away from the good versus evil story that seeks to persuade Americans that the sole reason for their economic problems is, on my side of the aisle, the greedy monopolistic corporations; or, on Bryan’s side of the aisle, immigrants or Mexicans. The point is we have a system that is driven by the need to dumb down the good versus evil story.

OXTOBY: Goodwin, in your role as a judge, do you see this type of dynamic when you need to make judgments?

LIU: In the courts, the hallmark of our work is civil and rational examination of disputes that people bring to us. We have rules of procedure and evidence; it isn’t a matter of who shouts the loudest. And judges know that many issues are not good versus evil but rather have nuance and require careful listening. One of the best parts of the Commission has been the voices of citizens from across the country in the listening sessions. When you listen to people, a lot of the polarization melts away because they are not talking in the terms that pundits and commentators use, or what you see on social media. They are talking in much more practical terms about their lives. One way to help reduce some of the polarization is to have these conversations on those terms.

In a different capacity, I sit on a medium-sized foundation board in California called the Irvine Foundation, which is dedicated to low-wage workers and worker mobility. Two weeks ago we did a site visit. We went to San Bernardino in the Inland Empire, which is one of the biggest logistics transportation hubs in the country. Amazon, FedEx, UPS, Staples, and Walmart have huge operations there. In fact, warehouses now occupy more than a billion square feet of the land in these places that used to be farmland. People reminisce about missing the smell of manure, but that has been replaced by other things that are causing environmental problems because of all the trucks that are coming in and out of the community. Though the jobs are plentiful, they are low-wage and often do not result in advancement. And that is why in many of these warehouses there is over 100 percent worker turnover within the span of a year and a half. These communities are trying to figure out how are we going to sustain these industries because they are chewing through the workers so rapidly.

On the other hand, there are positives, like housing – a lot of Los Angeles transplants are going there – and educational institutions and infrastructure. It is an area that is full of possibility, but the economic model is keeping the area from realizing its full potential because it is fundamentally extractive, according to some of the people there. The externalities of these companies are concentrated in that physical space, but the benefits are worldwide. Our packages that are going all over the country are getting there on time because these workers are hustling, with the benefits going elsewhere. That is a structural issue – place-based disparities really make an impression. We often see these issues – wages, working conditions, development and environmental issues – play out in the courts.

OXTOBY: One of the things that we have been talking about at the Academy is the future of American democracy. In 2020, the Academy’s Commission on the Future of Democratic Citizenship published Our Common Purpose: Reinventing American Democracy for the 21st Century. There are intersections between the economic world and strengthening American democracy. Is the Select Committee looking at these questions?

STEIL: I would view it as a key piece of the puzzle. I don’t know that it is the inherent driver of the Select Committee, which is more focused on how we make sure that everybody has a shot at the American dream, whatever that may mean to you. How do we get people sustainably into the middle class? I don’t want to speak for the Chairman, but I don’t think it is lost on either of us that if there are a lot of people in this country on the left, on the right, and off the scale altogether, who don’t believe that the system is fair, who don’t believe that they are getting a fair shake, then they are going to look for alternatives. Right now, there are many people who do not feel that the economy is working for them. And so we are looking at what other policies can we put in place that allow this structure to work for you and your family. And if we are successful in that, then there are tangential benefits to American democracy.

HIMES: I agree with Bryan. Earlier I said that what really grabs me is how economic disparity drives political rage. If I can offer a note of optimism to the Academy’s Commission, I think the problems that we are struggling with, namely, economic disparity, are really hard. They are intellectually and politically hard. How do we disrupt a system of education that still hearkens back to the nineteenth century? Both of my daughters have the summer off. How do you disrupt the health care system that, in my opinion, has not served us well? Everyone is telling us that we have to do a lot better with childcare. And yet, we are having a hard time coming up with a policy proposal to get there.

I stand by my comment that economic disparity drives political instability. You can tick off six things that theoretically you could do very quickly: nonpartisan commissions for the drawing of congressional district lines, ranked choice voting around the country, Supreme Court eighteen-year terms, and the like. They are not that intellectually hard. More and more states are adopting ranked choice voting. These are technical things that you could do to depower the extremes in our politics and empower the center. I am not sure that the economic problems lend themselves to those theoretically quick technical solutions.

OXTOBY: Let’s turn now to the audience for some questions.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: As a retired professor from Harvard Business School, I worry a lot about the economic issues that you are raising. It is wonderful that the Select Committee and the Academy’s Commission have been going around the country listening to people’s voices. So, why is nothing being done? My argument is that we know what the problems are. The challenge is, how do you deal with the short-term nature of virtually every area of our world – from solving environmental problems to addressing income issues?

STEIL: You have hit on an aspect of human nature that a group of psychologists could comment on better than I am prepared to do. But it is a political challenge, and has been so since the founding of the country. The average person is concerned about tomorrow rather than next year. The challenge of policy-making is to say we have been running this American idea experiment for about 250 years. How do we take that and prepare ourselves to go into the next 100 years? We have huge challenges in front of us: for example, making sure that Social Security and Medicare are solvent for generations to come. So, I think it is a human nature challenge as much as it is a policy challenge.

HIMES: I think the collapse of the United States Senate into a short-term, politicized body has made things worse. The whole concept of the Senate, apart from tempering the passions of the House, was that Senators could abstract themselves away. With six-year terms instead of two-year terms, they could remove themselves from the demands of the right now in favor of a longer-term view. But for reasons that I cannot explain, the Senate has become as near-term focused as the House.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I want to thank you for modeling civil dialogue. I am puzzled by some of these persistent policy challenges that you identify. Representative Himes mentioned childcare, health care, and education. There are countries around the world that have solved these problems by providing universal childcare and universal health care. Is the Select Committee or the Academy’s Commission looking at international models of how to do this better than what the United States has managed to do?

HIMES: The answer is yes. The Select Committee had an interesting meeting with representatives of the OECD. I began my career in the private sector, so I am always looking at comparables. I think there are two political reasons why this is hard for us to do. One, we invest our money in the populations who vote, that is, our senior citizens. Just about half of the federal budget – through Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid – goes to the people who vote. Prenatal Americans don’t vote. The problems that come from underinvesting in two- and three-year-olds do not manifest themselves for several years. Two, the world has outsourced global security to the United States. So instead of investing in kids, we spend $800 billion a year on global security, and I don’t just mean on our national security. When it comes time to help the Ukrainians defeat the Russians, that is largely on us. You could argue whether that is good or bad, whether we should be the policeman of the world, but the fact of the matter is we spend $800 billion, which is an inconceivable amount of money. Five years ago, China spent more on defense than the next ten countries combined spent on their own security. So, we have challenges politically that prevent us from engaging with some of the fairly obvious solutions that have been modeled by other countries.

STEIL: I would offer that there is a lot more nuance in the data when we look at the comparables. What Chairman Himes just referenced on the security side is real. The land war playing out in Europe with their dependence on U.S. military technology is one piece of that puzzle. If you look at the quality of health care in the United States, it is often seen as being superior to that in other countries. If we look at overall consumption in the United States and the standard of living across the board, we see a much more nuanced analysis on the comparables between the United States and other countries.

OXTOBY: The Academy’s Commission is looking globally for examples that we might try to model. We are looking at the American situation, of course, but using ideas from other countries. For example, one of the issues we discussed earlier today concerned people coming out of prison and what their opportunities are. Other countries are way ahead of us in this area.

JIM FALLOWS: The question for our three public officials here is discussed in a recent article by Peter Leyden entitled “The Great Progression.” His argument is that we often compare the problems of this era to the Gilded Age, and compare the hope for reforms to those in the Progressive Era. Leyden says that progressive reforms are already happening across the United States and that the media and our political narrative have not caught up. He notes that we will look back upon this era as a time when a lot of loosely affiliated reform movements around the country were dealing with problems and they suddenly found some coherence in the next years. Does Leyden’s argument make sense to you in your public roles?

LIU: I think as evidenced by the work of this Select Committee as well as that of the Commission and allied efforts that it would be premature to say that some new Progressive Era is dawning. I think what is happening is a serious reexamination of the social contract, and it is being called for by precisely the voices that the Select Committee and the Commission have been hearing from. Many of the basic underpinnings of how the economy was built and how prosperity was to be shared are not the same as they were or they don’t exist as they did forty or fifty years ago. I would not hazard a strong prediction as to where this is all headed. Some of the efforts that we see going on right now are testing some basic assumptions that have been in our economy for a long time.

STEIL: I think we have some time before we are able to look in the rearview mirror and say which policies were successful, and which were not. If we use a European comparison to look at energy policy and when you have an energy supply that is not nationally secure – and that is going to happen to our European allies this winter – the policy decisions could be very significant and very severe. In the rearview mirror, we will have a different perspective than they probably did even four years ago as Germany was moving to close nuclear power plants, making themselves further dependent on Russian oil and natural gas.

We could look at the labor policies we put in place in the United States. Before the pandemic we saw real wages at historic highs across demographic groups, and above the median for women, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and veterans. We are now in a period of rising inflation and high costs. The Chairman and I will get into long debates, neither of us with a PhD in economics, as to the cause and the driver of that inflation, but we have seen real wages falling for many folks. Previously, the tight labor market uniquely benefited those in the lowest quintile, with significant and meaningful benefits to our country as a whole. We have also seen some labor policies put in place that I think have moved us in the wrong direction. I think we will look back and identify some things that turned out correctly and some things that didn’t, and that is part of our American experience and experiment.

HIMES: I have not read Leyden’s article, but I have been sitting here thinking, should I feel optimistic? Is this, in fact, an era of progressivism? I would describe myself as a temperamental optimist. The Affordable Care Act didn’t fix our health care system, but it was an improvement over what existed before. Twenty million Americans were covered and that was an improvement. Institutions are grappling with race and gender more intensely than I have seen in my lifetime, and it was accelerated in May 2020 when America watched the horror of what happened to George Floyd. The private sector – J.P. Morgan, Walmart, and Amazon – is saying we have to do better.

Though we can find bright spots, I come back to the fact that the basic foundations of prosperity – for example, the housing market – are not serving us well. People cannot afford to live where the jobs are. Our educational system is not penetrating down to the people who really need to be uplifted. We are still so far away from a logical and smart health care system. So until we see these sectors brought into the twenty-first century, we are going to have a difficult time saying we are living in a new Progressive Era.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: In the wake of Hurricane Ian, has the public perception of disaster events related to the climate crisis shifted the needle in terms of housing or national security policy?

HIMES: That is a very broad question. In my fourteen years of service in the House, the conversation on climate change has improved significantly. And we have achieved some things. It was sadly not bipartisan, but we did pass a bill that included a $400 billion investment in the migration of our energy system toward something more sustainable. The problem has been that we are moving far too slowly. The repeated devastation of coastal areas has not been enough to accelerate what we need to do.

What I am going to say may annoy some people in the room, but the events of the last two years, in particular, the spike in gasoline prices and of energy prices generally, have in some ways helped us to have a saner conversation than before. Now that America has spoken about how it feels about a world in which Russian hydrocarbons are not on the market, we are having a more pragmatic and, therefore, constructive conversation. I hope Bryan comments on this. My Republican friends are not saying, “Don’t migrate to sustainable energy sources.” Rather they are saying, “Just don’t do it in a way that is devastating to economies and to households.” So if you are a hard-core climate person, politically speaking, you may not be happy about this, but where we work, it is good to have a pragmatic, fact-based conversation because that is how we make progress.

STEIL: To build on that, I am not an energy policy expert per se, but I see a need to have a secure energy supply. We are watching on the world stage right now in real time the risks of not having a secure energy supply. In terms of national security for the United States, we need to make sure that there is a nationally secured supply of energy. I think there is a lot of middle ground in our energy approach. Nuclear is going to be a part of that conversation, even though it is always pushed to the side.

OXTOBY: As some of the people in the audience know, the American Academy has a Commission on Accelerating Climate Action that is looking at these questions. Our Climate Commission is bringing together people from the military and from the private sector, and talking about how best to communicate about these issues so that the general public understands them better.

This has been a fascinating discussion. I would like to thank Representative Himes and Representative Steil for their time, insight, and work on these important issues, and for participating in our program this evening. I would also like to thank Justice Liu and Ann Fudge for their comments. And finally, thank you all for joining us.

© 2023 by Ann Fudge, Jim Himes, Bryan Steil, and Goodwin H. Liu, respectively

To view or listen to the presentation, visit www.amacad.org/news/bipartisan-economy-congress-himes-steil.