Section 3: Public Research Universities Provide Quality Educational Opportunities and Programs at an Efficient Cost

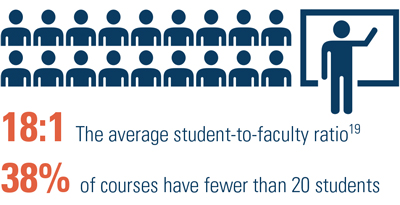

At public research universities: |

|

|

Public research universities experiment with innovations in teaching and learning, including “flipped” and “hybrid” classrooms (in which lectures take place online and class time is devoted to discussion), and other alternative teaching methodologies that take advantage of information technology and online education.18 Projects such as the Global Classrooms Initiative at the University of Maryland provide financial support to faculty who develop innovative project-based courses that use digital technology to bring together students from partner universities around the world. The University of Memphis Finish Line Program targets students who come close to graduating but have to stop-out and matches them with online, self-paced courses to help them complete their degrees. And through extension centers and lifelong learning institutes, public research universities are able to educate tens of thousands of citizens who would otherwise be beyond the reach of their campuses.

Institutional leaders align academic initiatives with the strengths and needs of the region and the nation. In 2013, public research universities awarded 41 percent of all baccalaureate or graduate level degrees/certificates in areas of national need (as defined by the federal government).21 Through these universities, students also gain access to internships and co-op experiences in local and regional companies, in some cases earning pay for their work. More than one in every four students at public research universities held an internship in 2012–2013, and one in ten interned under the direction of a university faculty member over that same period.22 Public research universities provide the platform and incentive for companies and students to engage with each other.

Undergraduates at public research universities benefit from faculty and graduate-student

mentoring. Students learn from cutting-edge researchers, in all disciplines,

who share new knowledge and the excitement of discovery through their teaching.The

many available opportunities for undergraduates to participate in research provide

invaluable hands-on application of classroom learning and skills training for the

future.23

Undergraduates at public research universities benefit from faculty and graduate-student

mentoring. Students learn from cutting-edge researchers, in all disciplines,

who share new knowledge and the excitement of discovery through their teaching.The

many available opportunities for undergraduates to participate in research provide

invaluable hands-on application of classroom learning and skills training for the

future.23

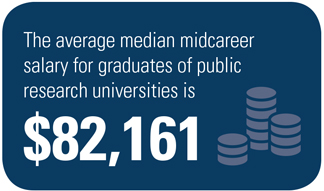

For graduates of public research universities, a college education (including tuition, living expenses, and foregone income) typically pays for itself within five to seven years of postgraduate employment.24 Public research universities hold the second highest graduation rate among all Carnegie-classified public colleges and universities (trailing only public art, music, and design schools),25 and job opportunities for college graduates are far better than for the general population and unemployment rates are lower.26 The average median midcareer salary for graduates of public research universities is $82,161.27 Over the last fifty years, the percentage of underpaid college graduates (defined as making less than the median pay of high school graduates) has decreased by one-third.28 Although there are differences in earning potential across majors, especially early in a graduate’s professional life, college graduates in all majors earn at least 60 percent more than high school graduates over the course of a career.29

Undergraduate Research on Campus and Beyond |

|

|

Over 1,800 undergraduate students participate in the Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program at the University of California, Berkeley. Students have the choice between working on semester- or year-long faculty-led projects across all academic departments. At Miami University in Ohio, more than 2,000 undergraduate students work with professors on funded research each year. In the annual spring Undergraduate Research Forum, undergraduates have the unique opportunity to publish and present to the university community on topics ranging from eye tracking and face processing to wine-drinking behavior in millenials. University of Nebraska’s Undergraduate Creative Activities and Research Experience program is complemented by skill-building seminars in topics such as ethics, data management, networking and presentations, and preparing for graduate school. In FY 2014–2015, hundreds of students completed faculty-sponsored projects in areas ranging from agriculture and natural resources to nursing. The University of Connecticut has ten different funding programs for its undergraduate student researchers. The UConn IDEA Grant provides up to $4,000 for student-designed projects targeting the arts, community service, entrepreneurship, and academic research. |

Changing Gears, part of the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program at the University of Michigan, is designed for community college transfer students to become a part of an ongoing research project in their field of interest and work alongside University of Michigan faculty and scholars on groundbreaking research. Undergraduates at Pennsylvania State University publish, perform, exhibit, and present their research projects at Penn State’s annual Undergraduate Exhibition, while also sharing their work at national conferences and meetings. Conference travel funding helps students attend events, giving them critical opportunities for networking and professional development. Posters at the Capitol celebrates the research and scholarly achievements of undergraduates from across the state of Tennessee. Students from the University of Tennessee and other state universities travel to Nashville to have lunch with legislators, meet the governor, and explain their various projects. |

ENDNOTES

18 William G. Bowen, Matthew M. Chingos, Kelly A. Lack, and Thomas I. Nygren, Interactive Learning Online at Public Universities: Evidence from Randomized Trials (New York: Ithaka S+R, 2012), http://www.sr.ithaka.org/sites/default/files/reports/sr-ithaka-interactive-learning-online-at-public-universities.pdf.

19 National Center for Education Statistics, IPEDS.

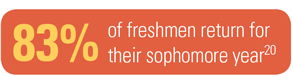

20 Further, one-quarter of all public research universities have retention rates of 90 percent or greater for first-time, full-time freshmen. See U.S. News & World Report, U.S. News College Compass (2015).

21 Areas of national need as identified by the U.S. Department of Education’s Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need Program include: Biological Sciences/Life Sciences, Chemistry, Computer and Information Sciences, Engineering, Foreign Languages and Literatures, Mathematics, Nursing, Physics, and Educational Evaluation, Research, and Statistics. See National Center for Education Statistics, IPEDS.

22 Krista M. Soria, Matt Johnson, and Alex Reinhard, “High-Impact Practices and College Students’ Development of Pluralistic Outcomes,” a paper presented at the International Leadership Association Conference in San Diego, California, on November 2, 2014.

23 Susan H. Russell, Mary P. Hancock, and James McCullough, “Benefits of Undergraduate Research Experiences,” Science 316 (5824) (2007): 548–549.

24 Calculations total student living expenses, tuition, fees, and foregone income over four to six years. They then compare the incomes of college-educated professionals to the total cost of college. Assumptions based on Henry E. Brady, “What’s the Problem with Higher Education in California?” notes from a presentation on “Higher Education Finance in California” given in Sacramento, California, on November 14, 2014; David H. Autor, “Skills, Education, and the Rise of Earnings Inequality among the ‘Other 99 Percent,’” Science 344 (2014): 843–851; and Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, The Race between Education and Technology (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2008).

25 National Center for Education Statistics, IPEDS.

26 Sandy Baum, Jennifer Ma, and Kathleen Payea, Education Pays 2013: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society (New York: The College Board, 2013), https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/education-pays-2013-full-report.pdf. See also Anthony P. Carnevale, Stephen J. Rose, and Ban Cheah, The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime Earnings (Washington, D.C.: The Georgetown University Center on Education and Workforce, 2011), https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/collegepayoff-complete.pdf.

27 Note this average

is for midcareer salaries of alumni with bachelor’s degrees only. See PayScale,

“2014–2015 PayScale College Salary

Report,” http://www.payscale.com/college-salary-report.

28 The percentage of college graduates earning less than the median income of high school graduates dropped from 25 percent in 1960 to 17.7 percent in 2010. See Matthew T. Lambert, Privatization and the Public Good: Public Universities in the Balance (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2014), 66–67.

29 Baum et al., Education Pays 2013, “Figure 1.2: Expected Lifetime Earnings Relative to High School Graduates, by Education Level,” http://trends.collegeboard.org/education-pays/figures-tables/lifetime-earnings-education-level.