Building Educational Capacity

According to the most recent data on language learning in the European Union, 66 percent of all European adults report having some knowledge of more than one language.29 The share of U.S. adults who report similar knowledge is closer to 20 percent, and very few speak, read, or write proficiently in a second language.30 An estimated 300–400 million Chinese students are now learning English, compared with about 200,000 U.S. students currently studying Chinese.31 The geographical and historical circumstances in the United States are, of course, very different (as is the relative ease of mastering the twenty-six-character English alphabet), and the pressure to learn a second language is certainly less persistent in an English-speaking nation. China’s commitment to English suggests that it has and will continue to have a special status among world languages, a status that gives the United States a competitive advantage in certain aspects of global trade and international exchange. But the wide disparity between the European or Chinese approach to languages and the U.S. approach suggests that we, as a nation, are lagging in the development of a critical twenty-first-century skill—and that we risk being left out of any conversation that does not take place in English. We can and should teach more languages to more people.

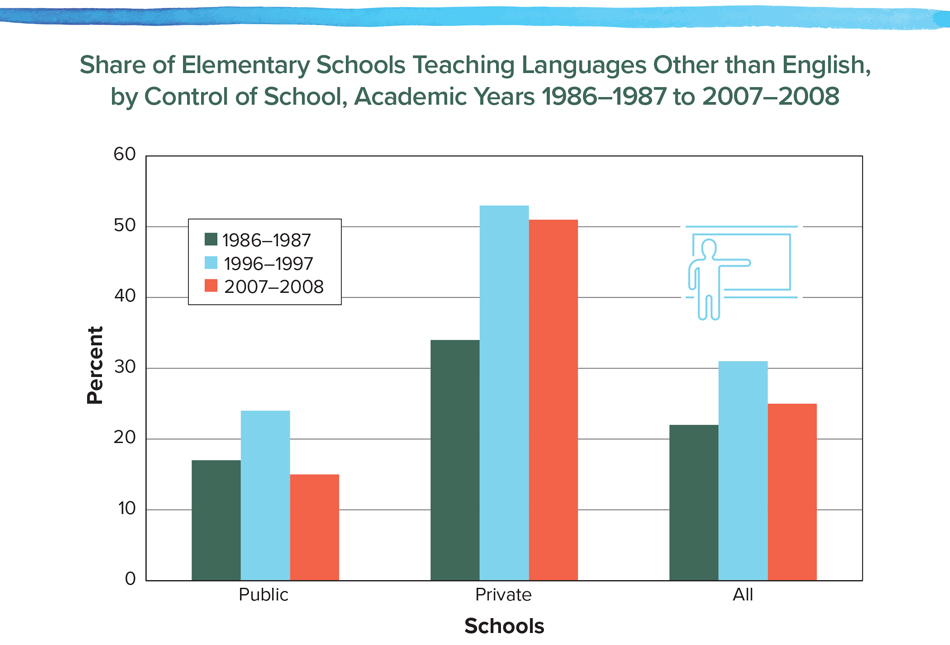

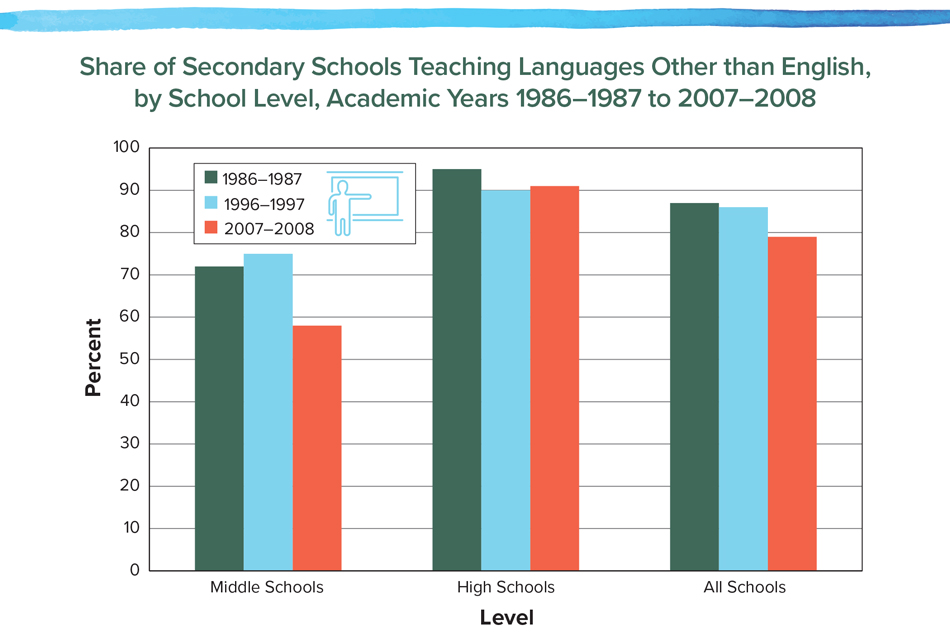

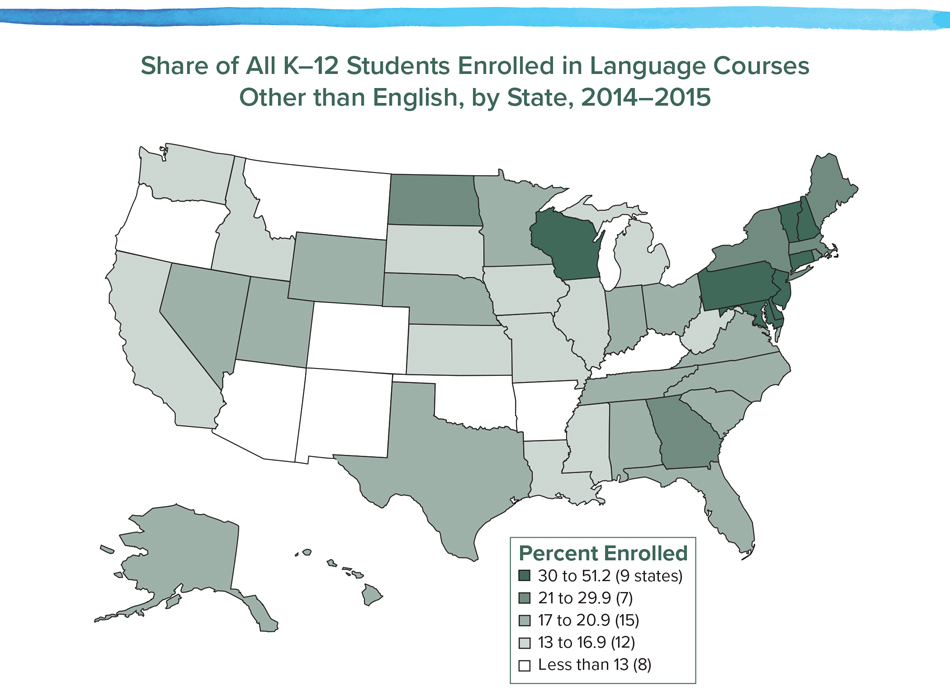

Functional ability in a second language comes in many forms and a range of skills, including listening comprehension, speaking, reading comprehension, and writing—up to and including the ability to live and work abroad. Each skill set and level of ability is valuable, useful, and deserving of encouragement. The ultimate goal of any coordinated effort to improve language learning—for students, parents, school districts, states, and the nation as a whole—should not be a standardized pursuit of a particular level of competency, but rather improved access to language education for all U.S. citizens, irrespective of geography, ethnicity, or socioeconomic background. As children prove especially receptive to language education—they spend much of their time in educational settings and can develop language skills gradually throughout their lives—it is critical that language education begin at the earliest possible moment in the educational continuum. Therefore, this overarching goal can be expressed more specifically as a desire to see every school in the nation offer meaningful instruction in world and/or Native American languages as part of their standard curricula. Across the nation, there has been a significant decline in the number of middle schools offering world languages: from 75 percent in 1997 to 58 percent in 2008.32 Over the same period, there was a 6 percent decline in the number of elementary schools that taught languages other than English, from 31 percent to 25 percent; the outlook is particularly bleak in the nation’s public elementary schools, only 15 percent of which offered a program for languages other than English, compared with more than 50 percent of private elementary schools.33 This disparity of access and opportunity, mirroring other forms of systemic inequality, must be addressed immediately, beginning with a recommitment by school administrators at public institutions in particular. Before- and after-school enrichment programs can be a useful supplement to classroom learning, and this Commission encourages the development of more programs through public-private partnerships and enhanced collaboration between schools and local communities. But the only way to ensure that every child has access is for every public school to offer language education as part of its standard course of instruction.

Source: Nancy C. Rhodes and Ingrid Pufahl, Foreign Language Teaching in U.S. Schools: Results of a National Survey (Washington, D.C.: Center for Applied Linguistics, 2010), 22.

This is a tall order. School curricula are already overloaded and, over the past decade, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education has been a national priority; but language must be seen as complementary to, rather than as competing with, STEM. But even if language learning becomes a national priority parallel to the emphasis on STEM education, we do not have enough certified language teachers at any level to meet the demand. According to the U.S. Department of Education, forty-four states and the District of Columbia currently report a shortage of qualified K–12 language and/or bilingual teachers for the 2016–2017 school year.34 Indeed, more states report a teacher shortage in languages than in any other subject. And since this count depends entirely on the states’ self-reporting, the shortage may be even more significant than it appears.

Source: Nancy C. Rhodes and Ingrid Pufahl, Foreign Language Teaching in U.S. Schools: Results of a National Survey (Washington, D.C.: Center for Applied Linguistics, 2010), 23.

This workforce issue is further complicated by a misalignment between the current infrastructure for language education and the emerging science of language acquisition. Language instruction in the United States typically begins in middle school or high school—a practice that ignores young learners when they are most receptive—when they have time to devote to their studies, when they are already in school and engaged in learning activities, and when they have a much longer timeline for developing their skills before they reach adulthood. Language instruction should therefore begin much sooner in U.S. schools, even as early as preschool. The structural challenges to such an adjustment are significant, including the need for system-wide staffing and curricular changes, but the benefits would be immediate and far-reaching.

Source: American Councils for International Education, American Council on the Teaching for Foreign Languages, Center for Applied Linguistics, and Modern Language Association, The National K–16 Foreign Language Enrollment Report 2014–15 (Washington, D.C.: American Councils for International Education, 2016), http://www.americancouncils.org/national-k-16-foreign-language-enrollment-report. Statistics on European students from Eurostats, “Foreign Language Learning Statistics,” September 2016, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7662394/3-23092016-AP-EN.pdf/57d3442c-7250-4aae-8844-c2130eba8e0e.

Digital technologies can help address at least some of these challenges. Blended learning models, through which students receive some part of their curriculum digitally—often through practice exercises, video, or interactive games—are particularly beneficial in communities with a short supply of language teachers. Young children have proven especially responsive to programs that alternate between personal instruction and online enrichment.35 By creating international exchanges over Facebook and Instagram, and even direct communication with students in other countries over Skype, many K–12 teachers have incorporated social media into their lesson plans as a way to explore other countries without having to travel. In addition, an emerging category of language apps for computers and smartphones—Lingua.ly, Quizlet, Memrise, Duolingo, and GraphoGame, for example—are introducing world languages to students on their own time. These apps are a promising gateway for learners of all ages and an exciting new subject for research about the efficacy of technological innovation in language instruction.

Over the coming decades, progress in language education will continue to be influenced by advances in technology and research including:

- Artificial intelligence and deep learning, through which computers process multiple layers of data;

- “Big data” solutions to learning and instruction;

- Translation assistance;

- Cognitive technologies that mirror human processes, like speech recognition and natural language processing;

- Human-systems interface design, which govern the ways humans and machines interact;

- Systems for gestural, eye movement, and audio-visual (including facial) recognition;

- Low-cost microphone arrays and noise reduction circuitry for improved voice recognition; and

- The localization of speech in noisy, real-world environments.

Apple’s Siri, Amazon Echo, Google Home, and IBM’s Watson already combine many of these technologies, and we can expect more advancements and improvements in the near future. Critical to all of these developments will be our continued support for research—already underway on university campuses and in laboratories across the nation—in a variety of areas, including linguistics, education, second language acquisition, computer science and artificial intelligence, cognitive science, and electrical engineering.Such technology should play a supportive role and can even be a motivating factor in encouraging more people to learn more languages. In many ways, there have never been more available options for pursuing a second language. But technology should not be seen as a replacement for the sound principles of second language acquisition. Any successful program in language education requires at least some direct communication with a qualified instructor who can teach complicated concepts like context, speaker intent, and shades of meaning. Each state should therefore commit to increase the number of language teachers in P–12 education so that every child in every state has the opportunity to learn a language other than English in an academic setting, whether the child is experiencing a second language for the first time, mastering a language he or she already speaks at home, or attending a school taught in a Native American language.

Given the dearth of available data about language instruction at the state level, it is difficult to assess the exact size of the national teacher shortage. Forty-four states report that they cannot find enough qualified teachers to meet current needs, but record-keeping has been regrettably imprecise, in part because every school district in the nation responds to the teacher shortage in its own way (by cutting classes, by combining classes, by contracting before- or after-school enrichment programs, to name a few). We do not have sufficient information about these district-level responses to attach a specific number to the national teacher shortage, and encourage any study that advances our knowledge of its size and scope. Nevertheless, we can infer from current hiring initiatives that the need is great and can only be met through a series of efforts involving federal, state, and local cooperation as well as international partners and new incentives. The Dallas Independent School District adds a $3,000 annual stipend to a typical teacher salary to attract new multilingual teachers, and hires as many as five hundred bilingual teachers each year.42 President Barack Obama’s 1 Million Strong initiative, a partnership with Chinese president Xi Jinping to expand the number of U.S. K–12 students learning Mandarin Chinese to one million, includes a goal of recruiting and certifying five thousand new teachers by 2020.43 U.S. mainland schools recruited almost sixteen thousand teachers from Puerto Rico between 2008 and 2013.44 And these numbers only begin to outline the scope of the national need.

Nevertheless, several efforts that are already underway, including state-level language initiatives in Utah and Delaware, have proven that it is possible to focus on language learning as an educational priority. More states should follow their lead.

Drawing on decades of innovation in world language education in Europe, Asia, and the United States, as well as the long history of federally mandated language education efforts for children who do not speak English, the Utah state senate passed the International Education Initiative in 2008.45 The Initiative made funding available for dual language immersion in Chinese, French, Spanish, and, a few years later, Russian and Portuguese. At the same time, Governor Jon Huntsman, Jr., led the creation of a K–12 language roadmap for Utah to address the needs for language skills in business, government, and education. Six years later, at least thirty thousand students were enrolled in immersion programs (in which half the day’s teaching takes place in a language other than English), most beginning in the first grade.46 The results have been startling: over 80 percent of students participating in dual language immersion programs are functioning in their second language by the third grade, and the Utah state legislature reports that such students appear to score higher on standardized tests in English language arts as well as math, when compared with students not enrolled in dual language immersion programs.47Following Utah’s success, Delaware became the second state to implement dual language immersion programs when, in 2011, Governor Jack Markell set aside $1.9 million in the state’s annual budget for programs in Spanish and Mandarin Chinese and set the goal of enrolling ten thousand primary and secondary school students in these programs by 2022. Indiana, Rhode Island, and Virginia have established pilot programs.48 California residents have recently voted to approve Proposition 58, empowering public schools to create bilingual and multilingual programs for the first time since 1998.49 And the New York City Department of Education has committed $980,000 in federal funding to thirty-eight new K–12 bilingual programs for the 2016–2017 school year, including twenty-nine dual language and nine transitional bilingual educational programs, serving more than 1,200 students.50 Given all of the financial and social pressures on such a large, urban school district, New York’s commitment is particularly noteworthy as affirmation of the need for more language education in the twenty-first century, and as proof that more is possible even under the most challenging circumstances.

These initiatives are models for the rest of the nation. But they are not scalable unless schools in other parts of the country can find and hire enough qualified teachers to teach more students.One way to address teacher shortages directly is to distribute available talent more effectively. Teachers of languages other than English can be found in every corner of the nation, but some regions feature more linguistic diversity than others, and some may even have a surplus in a particular language. In such cases, the incompatibility of state certification requirements may be preventing the flow of otherwise qualified teachers to regions where they are most needed. States should coordinate their credentialing systems so that qualified teachers can move to and find work in regions where there are significant shortages, without unnecessary obstacles. Most states already accept out-of-state certification and give credit for experience for language teachers, but not all, and the requirements vary greatly among states.52 A more streamlined system could greatly enhance the national teaching workforce.But, in the end, the real test of any new effort to increase the nation’s capacity in languages will depend on our ability to attract more people to the teaching profession. Like science, math, and English, languages should be considered part of a “core curriculum,” and language teachers should be valued for their expertise and honored for preparing students for life in the twenty-first century. They should be considered integral members of the education system and given the same opportunities for professional training and advancement as teachers in other “core” subject areas. While the nation is building its language workforce, prospective teachers should be offered incentives to choose languages, including Native American languages, as their field of expertise. Currently, in recognition of the teacher shortage, the Federal Perkins Loan program will forgive up to 100 percent of a need-based loan for students training to become language teachers. But the Department of Education offers no such forgiveness for Direct Loans, which support undergraduate and graduate students irrespective of need.53 Given the importance of the task before us, and the need to attract as many talented and enthusiastic language teachers as possible, the federal government should consider a more ambitious debt forgiveness program.

In addition, teacher education programs need to focus on recruiting more students into this specialty. And two- and four-year colleges and universities must ensure that future teachers—indeed any student who requires or wishes to pursue intermediate or advanced proficiency in a language—can find the courses they need. Language programs were particularly vulnerable during the Great Recession: many administrators, faced with difficult budgetary decisions, sacrificed language courses and requirements in order to preserve other disciplines.55 These cuts did not always serve the best interests of students, who can reap professional rewards for achieving even moderate proficiency in a second language.62 Nor do they serve the interests of a nation that requires an ever-larger cadre of bilingual citizens to maintain its place in the international community. Rather than eliminate programs or requirements, two- and four-year colleges and universities should find new ways to provide opportunities for advanced study in languages, through a recommitment to language instruction on campus, blended learning programs, and the development of new regional consortia that allow colleges and universities to pool language resources.63 Blended learning programs and consortia will be particularly important as we increase the number of learning opportunities in less commonly taught languages like Arabic, Persian, and Korean. Only by maintaining such offerings in higher education can we ensure that we will have the teachers and linguistic and cultural experts we need for life and work in the twenty-first century.

In addition, there are particular challenges in developing teachers of Native American languages. Until passage of the NALA in 1990, there was no official federal policy in support of Native American languages, and Native American languages were largely excluded from the nation’s classrooms. As a result, the majority of Native American languages are spoken primarily by tribal elders. Few materials exist to teach Native American languages at any level, including at the tertiary education level. More college programs are needed to develop high proficiency in Native American languages along with Native American language teacher training programs. These might be developed through cooperative work among those relatively few universities and colleges, including tribal colleges and universities, that teach Native American languages.

A Note about Data

Many states already collect data about math and science enrollments for K–12 education in order to better understand and manage which students have access to subject matter within public academic settings. In response to national surveys and direct requests, some states can provide data about language learning, but there is no mandate for the consistent collection and maintenance of such data, as there often is in other disciplines. State and federal policy-makers could develop more informed educational and curricular goals for language learning if:

• Data were collected at scheduled intervals, allowing for closer monitoring of total enrollment and the distribution of enrollment among languages and grade levels; and/or

• Collection were standardized across states to provide a greater understanding of the state of language learning across the nation.

Such data collection efforts could yield important information about student demographics, teacher qualifications and expertise, and the types of instruction available around the nation. It might also help inform the development of student performance metrics.

The Cognitive Benefits of Language Learning

Recent studies have suggested that language learners derive myriad secondary benefits from language instruction.

- The September 2013 issue of the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology analyzed two studies that found that bilingual children have stronger working memory—the ability to retain and manipulate distinct pieces of information over short periods of time—than do monolingual children.36

- A 2013 assessment of the Utah Dual Language Immersion program showed that children in the program gained improved memory and attention, problem-solving capabilities, primary-language comprehension, and ability to empathize with other cultures and people.37

- A study in the September 2009 issue of Cognition showed that bilingual children have greater executive functioning—focus, planning, prioritization, multitasking—than monolingual children.38

- A 2015 study published by researchers from the University of Chicago in Psychological Science showed that “multilingual exposure may promote effective communication by enhancing perspective taking,” a fundamental component of empathy.39

- A 2007 study published in Neuropsychologia suggests that bilingual patients at a memory clinic presented dementia symptoms four years later, on average, than their monolingual counterparts. A similar study in Neurology found that bilingualism delayed the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.40

Scientists are just beginning to study the cognitive benefits of language learning. Continued support for research will help to verify these benefits and identify the most promising directions to pursue.41

The Seal of Biliteracy

The Seal of Biliteracy is an award presented by a state department of education or local district to recognize a student who has attained a state-determined proficiency in English and one or more other world languages by high school graduation. The second language can be a native language, heritage language, or a language learned in school or another setting. The Seal becomes part of the student’s high school transcript and diploma, a statement of accomplishment that helps to signal a student’s readiness for career and college, and for engagement as a global citizen.

The Seal of Biliteracy program began in California, as a collaboration between Californians Together and the California Association of Bilingual Educators, and guidelines for the Seal have been developed jointly by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL), the National Council of State Supervisors for Languages (NCSSFL), the National Association of Bilingual Education (NABE), and the TESOL International Association. Twenty-three states and the District of Columbia now offer a state Seal of Biliteracy. We urge more states to adopt the Seal.

The Benefits of Dual Language Immersion

A recent study of students in dual language immersion programs, which controlled for factors such as socioeconomic disparity, found that in a randomized selection of students, those who participated in dual language immersion programs achieved higher English language arts performance in dual immersion classes than those who did not. By the time dual language immersion students reached the fifth grade, they were an average of seven months ahead in English reading skills compared with their peers in nonimmersion classrooms. By the eighth grade, students were a full academic year ahead, whether their first language was English or another world language. These findings suggest that learning a second language helps students tackle the nuances and complexities of their first language as well.

In many cases, dual language immersion programs are also more cost-effective than other kinds of language courses. Rather than adding additional units to an already crowded curriculum, or requiring new teachers dedicated only to language instruction, immersion courses incorporate language instruction into preexisting coursework (in math, science, reading) and rely on the same teachers who teach other subjects.51 However, they also require teachers who can teach a broad curriculum in two languages, a challenge, at least in the short-term, for many school districts around the country.

Dana Banks

Deputy Chief of Mission, U.S. Embassy Lomé, Togo

Dana Banks earned her bachelor’s degree in political science from Spelman College and her master’s degree in international affairs from the Maxwell School at Syracuse University. A Department of State Pickering Fellow and a College Fund Institute for International Public Policy Fellow, she studied and interned abroad before joining the Foreign Service in 1999. In addition to her current position in Togo, Banks has lived overseas in Tanzania, Haiti, and Thailand while serving various roles for the U.S. State Department. She speaks French, Haitian Creole, and Thai.

“My education has greatly aided me in understanding other cultures. . . . I think it’s important for Americans to have the knowledge and foreign language skills of other cultures, because the world is indeed interconnected through the Internet, through advances in travel and communication—the world is moving at a fast pace.”54

Language Consortia in Higher Education

Given the number and diversity of world languages—as well as variations in student interest, the availability of faculty, and research capabilities—two- and four-year colleges and universities face a significant challenge as they try to provide education in as many languages as possible. A growing number are now sharing faculty and resources to make more languages accessible to students:

The Big Ten Academic Alliance, a consortium of fourteen universities, uses its distance-learning CourseShare program to offer online classes in nearly sixty-five less commonly taught languages, including Uzbek and Dutch, to students at all of its member universities.56

The Five College Center for the Study of World Languages offers academic year courses in less-commonly studied languages for students at Amherst, Hampshire, Mount Holyoke, and Smith Colleges, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Course sessions meet on all five campuses and are part of a student’s regular course load.57

The Association of Independent Colleges and Universities of Rhode Island Language Consortium Program allows students currently enrolled in an undergraduate degree program at one of Rhode Island’s private institutions of higher education to enroll in language courses at any of the participating consortium schools in those courses that are not offered at their home institution.58

The UNC–NC State Language Exchange affords students the opportunity to enroll in courses (and attend through video conferencing) at campuses other than their home campus. Currently five language-specific exchanges exist: Greek-Latin, German, Russian, Portuguese, and Spanish. A sixth exchange called World Languages has been created to manage introductory courses in less commonly taught languages.59

The Shared Course Initiative is a collaborative arrangement among Columbia, Cornell, and Yale to offer via videoconferencing coursework in several languages that are not otherwise taught on a particular campus. The courses are taught “live” by an instructor at one institution; students attend a regular class in a designated classroom outfitted with videoconferencing technology.60

The National Coalition of Native American Language Schools and Programs brings together programs, public and private schools, tribal colleges, and other institutions of higher education that teach coursework through Native American languages at all levels, with extensive connections to other tribal-college and tertiary programs supporting education through Native American languages. The Coalition supports teaching in fifteen states and offers assistance to groups seeking to start programs in these and other states and American territories.61

Educating Students in Native American Languages

Case Study: Hawaii

In 1986, there were fewer than fifty children under age eighteen proficient in Hawaiian, and Native Hawaiian educational achievement had plummeted. Beginning in 1987, the state public schools incorporated children and methodologies from private, nonprofit schools called Pūnana Leo (language nests) in which classes are taught in Hawaiian. State data for 2013–2015 indicate that students from these schools are now graduating from high school on time at a rate of 3 percent above the state average and 8 percent above the Native Hawaiian average, and the classes of 2014 and 2015 attended college directly out of high school at a rate 15 percent above the Native Hawaiian average.64

Some colleges and universities, including Bryn Mawr, Princeton, and Yale, have instituted mandatory language study for undergraduates. They recognize Advanced Placement coursework as a qualification for higher-level language courses, rather than an exemption from language requirements. Not every college or university has the resources to institute such a policy immediately, but it is a laudable goal and worthy of serious consideration.

Federal Funding for Language Learning

At least twenty federal departments and agencies support research and development in language and communication technologies, including the Departments of State, Defense, Agriculture, and Health and Human Services, as well as the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation. The federal government also provides direct support for language education through the following acts of Congress, administered through the Department of Education:

Every Student Succeeds Act

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), was signed into law in 2015. The rewrite consolidated the most substantial K–12 foreign language programming at the Department of Education (the Foreign Language Assistance Program) into a state block grant called the Student Support and Academic Enrichment (SSAE) grants program. SSAE grants fund well-rounded education, efforts to improve school conditions and health, and strategies to promote the use of technology in schools. This program provides school districts with the option to fund language programming, but it remains unclear whether the appropriations committees will direct funding toward the initiative during FY 2017 or whether school districts will choose to direct this funding toward languages or a myriad of other uses. But the Act does present other funding opportunities:

- It is possible that school districts could use federal funding from Titles I and II for language education in support of “well-rounded” programming.

- Title III funding could be used to support language programs that also serve English Learners.

- A new, competitive Native American and Alaska Native Language Immersion Program is authorized at $1.1 million under Title VI of ESSA.

Higher Education Act

The Higher Education Act (HEA) was most recently reauthorized in 2008. Higher education funding for foreign languages falls under Title VI of the HEA and includes international education programs and foreign language studies, both domestically and internationally. Administered by the Department of Education’s Office of Postsecondary Education, these domestic programs are intended to strengthen language capability, and grants are awarded competitively to help fund centers, programs, and fellowships. Funding for domestic programs was reduced from $66.6 million to $63.1 million in FY 2013. However, funding has remained flat at $65.1 million from FY 2014 to FY 2016.

The Department also administers the Fulbright- Hays programs. These international programs are permanently authorized under the Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Act of 1961, and are designed to provide participants with first-hand overseas experience, increase the interaction between Americans and citizens from other countries, and strengthen language skills.65

In both the Title VI and Fulbright-Hayes programs, priority is given to students studying less-commonly taught languages.

The program funding was reduced in FY 2013 from $7.5 million to $7.1 million, but has remained constant since then. As of this writing, the funding levels for both domestic and international programs for FY 2017 have not been announced.

A twenty-first-century education strategy that promotes broad access, values international competencies, and nurtures deep expertise in world languages and cultures will require increases in these funding streams.66

ENDNOTES

29. “Foreign Language Skills Statistics,” Eurostat Statistics Explained, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Foreign_language_skills_statistics.

30. U.S. Census Bureau, “Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over for United States: 2009–2013.”

31. Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, “Can 1 Million American Students Learn Mandarin?” Foreign Policy, September 25, 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/09/25/china-us-obamas-one-million-students-chinese-language-mandarin/.

32. American Academy of Arts and Sciences, The State of Languages in the U.S.: A Statistical Portrait (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2016), 11.

33. Ibid., 9. This is in stark contrast to the 84 percent of K–8 students in the twenty-eight member nations of the European Union who have studied a second language. See Eurostats, “Foreign Language Learning Statistics,” September 2016, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7662394/3-23092016-AP-EN.pdf/57d3442c-7250-4aae-8844-c2130eba8e0e.

34. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education, Teacher Shortage Areas, Nationwide Listing, 1990–1991 through 2016–2017 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2016), http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ope/pol/tsa.pdf.

35. Liz Bowie, “In Baltimore Area Schools, Young Students are Learning a Foreign Language,” The Baltimore Sun, December 2, 2014, http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/education/bs-md-foreign-language-20141201-story.html#page=1.

36. Julia Morales, Alejandra Calvo, and Ellen Bialystok, “Working Memory Development in Monolingual and Bilingual Children,” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 114 (2) (2013), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23059128.

37. Utah State Office of Education, Critical Languages: Dual Language Immersion Education Appropriations Report (Salt Lake City: Utah State Board of Education, 2013), http://www.schools.utah.gov/legislativematerials/2013/Critical_Language_Dual_Immersion_Legislative_Repor.aspx.

38. Ellen Bialystok, “Components of Executive Control with Advantages for Bilingual Children in Two Cultures,” Cognition 112 (3) (2009), http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010027709001577.

39. Samantha P. Fan, Zoe Libermen, Boaz Keysar, and Katherine D. Kinzler, “The Exposure Advantage: Early Exposure to a Multilingual Environment Promotes Effective Communication,” Psychological Science 26 (7) (2015): 1090–1097.

40. Ellen Bialystok, “Bilingualism as a Protection Against the Onset of Symptoms of Dementia,” Neuropsychologia 45 (2) (2007), http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0028393206004076; and Moskowitz, “Learning a Second Language Protects Against Alzheimer’s.”

41. For more on the cognitive benefits of language learning, see Judith F. Kroll and Paola E. Dussias, Language and Productivity for All Americans (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2016), http://www.amacad.org/multimedia/pdfs/KrollDussias_April%205.pdf.

42. Corey Mitchell, “Need for Bilingual Educators Moves School Recruitment Abroad,” Education Week, January 25, 2016, http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2016/01/27/need-for-bilingual-educators-moves-school-recruitment.html.

43. Carola McGiffert, “Introducing Our 1 Million Strong Implementation Partners,” U.S. China Strong, http://uschinastrong.org/2016/09/25/introducing-1-million-strong-implementation-partners/.

44. Tim Henderson, “Why American Schools Are Starting to Recruit More Teachers from Foreign Countries,” The Huffington Post, October 13, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/10/13/schools-recruit-foreign-teachers_n_8287694.html.

45. For further information on the federal civil rights framework for the provision of programs to English Learners, see U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Education, “Dear Colleague Letter, English Learner Students and Limited English Proficient Parents,” January 7, 2015, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-el-201501.pdf.

46. Utah Immersion, “Why Immersion?” http://utahdli.org/whyimmersion.html.

47. Utah State Office of Education, Critical Languages: Dual Language Immersion Education Appropriations Report, http://www.schools.utah.gov/legislativematerials/2013/Critical_Language_Dual_Immersion_Legislative_Repor.aspx.

48. For an overview, see U.S. Department of Education, Office of English Language Acquisition, “Dual Language Education Programs: Current State Policies and Practices,” https://ncela.ed.gov/files/rcd/TO20_DualLanguageRpt_508.pdf.

49. Jazmine Ulloa, “California Will Bring Back Bilingual Education as Proposition 58 Cruises to Victory,” Los Angeles Times, November 8, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/nation/politics/trailguide/la-na-election-day-2016-proposition-58-bilingual-1478220414-htmlstory.html.

50. NYC Department of Education, “Chancellor Fariña Announces 38 New Bilingual Programs,” April 4, 2016, http://schools.nyc.gov/Offices/mediarelations/NewsandSpeeches/2015-2016/Chancellor+Farina+Announces+38+New+Bilingual+Programs.htm.

51. RAND Corporation, American Councils for International Education, and Portland Public Schools, “Study of Dual Language Immersion in the Portland Public Schools: Year 4 Briefing,” November 2015, http://www.pps.net/cms/lib8/OR01913224/Centricity/Domain/85/DLI_Year_4_Summary_Nov2015v7.pdf. See also Jennifer L. Steele, Robert O. Slater, Gema Zamarro, et al., “The Effects of Dual Language Immersion Programs on Student Achievement: Evidence from Lottery Data,” American Educational Research Journal (Centennial Issue) 53 (5) (forthcoming).

52. Swarthmore College, “State-by-State Chart for Policies on Reciprocity and Out-of-State Teacher Certification,” http://www.swarthmore.edu/Documents/State%20Certification%20Reciprocity.pdf (accessed December 12, 2016).

53. Federal Student Aid, U.S. Department of Education, https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/ (accessed January 19, 2017).

54. ACE/CIE, Engaging the World: U.S. Global Competence for the 21st Century, “Global Competence Video: Dana Banks,” http://www.usglobalcompetence.org/videos/banks_large.html.

55. Lisa W. Foderaro, “Budget-Cutting Colleges Bid Some Languages Adieu,” The New York Times, December 3, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/05/education/05languages.html.

56. Big Ten Academic Alliance, “Introduction,” https://www.btaa.org/projects/shared-courses/courseshare/introduction.

57. Five College Consortium, “Five College Center for the Study of World Languages,” https://www.fivecolleges.edu/fclang.

58. Association of Independent Colleges & Universities of Rhode Island, “Academic Programs: Language Consortium Program,” http://aicuri.org/initiatives/academic/.

59. North Carolina State University, “NC State Language Exchange,” https://fll.chass.ncsu.edu/undergraduate/language_exchange.php.

60. Yale Center for Language Study, “Shared Course Initiative,” http://cls.yale.edu/shared-course-initiative (accessed January 27, 2017).

61. National Coalition of Native American Language Schools and Programs, http://www.ncnalsp.org/about-the-coalition/.

62. Recent surveys of state and local job markets reveal a significant increase in the number of job postings that list language skills as a requirement. See American Academy of Arts and Sciences, The State of Languages in the U.S.: A Statistical Portrait, 17.

63. Colleen Flaherty, “More Than Words,” Inside Higher Ed, November 2, 2016, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/11/02/princeton-proposal-would-require-all-students-even-those-already-proficient-study.

64. ‘Aha Pūnana Leo, “A Timeline of Revitalization,” http://www.ahapunanaleo.org/index.php?/about/a_timeline_of_revitalization/ (accessed January 27, 2017); and Karen Lee and Jean Osumi, “Native Hawaiian Student Outcomes,” presentation at the Native Hawaiian Education Council Meeting, Honolulu, Hawaii, November 2016.

65. One Fulbright-Hayes Program, Group Projects Abroad—Advanced Language Training, is designed specifically to provide intensive language training for U.S. graduate and undergraduate students.

66. Office of Science and Technology Policy, Executive Office of the President, Report from the Interagency Working Group on Language & Communication (Washington, D.C.: Executive Office of the President of the United States, 2016), 14, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/NSTC/report_of_the_interagency_working_group_on_language_and_communication_final.pdf (accessed on January 19, 2017); and U.S. Department of Education, Higher Education: Fiscal Year 2017 Budget Request (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2016), https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget17/justifications/r-highered.pdf.