Developing Heritage Languages and Revitalizing Native American Languages

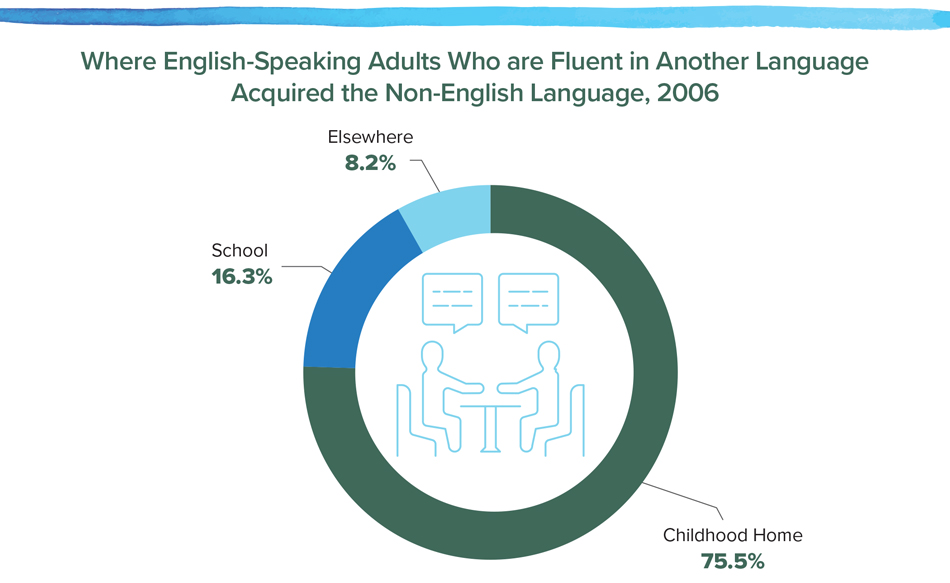

The United States need look no further than its own immigrant, ethnic, and Native American communities to find the seeds of a rich and diverse linguistic future. As of 2006, the most recent year for which such data are available, the overwhelming majority of U.S. adults who reported that they spoke a language other than English—including 37 million Spanish speakers and 2.9 million Chinese speakers—acquired that language at home.74 In most cases, language acquisition is associated with familial, cultural, and historical ties, rather than school-based curricula. In an immigrant nation like the United States, this circumstance should be considered an asset. Heritage speakers have a working knowledge of a second language even before they enter the classroom. Prior to any educational investments at the local, state, or federal levels, they have a head start in achieving the kind of biliteracy that would be as beneficial to them individually as it would be to the nation as a whole. Undoubtedly, they can only become proficient in their heritage languages through persistent study and ongoing instruction. But if we encourage them in this pursuit, by supporting the heritage and Native American languages already spoken in communities across the nation and helping these languages persist from one generation to the next, we would have the nucleus of a truly multilingual society.

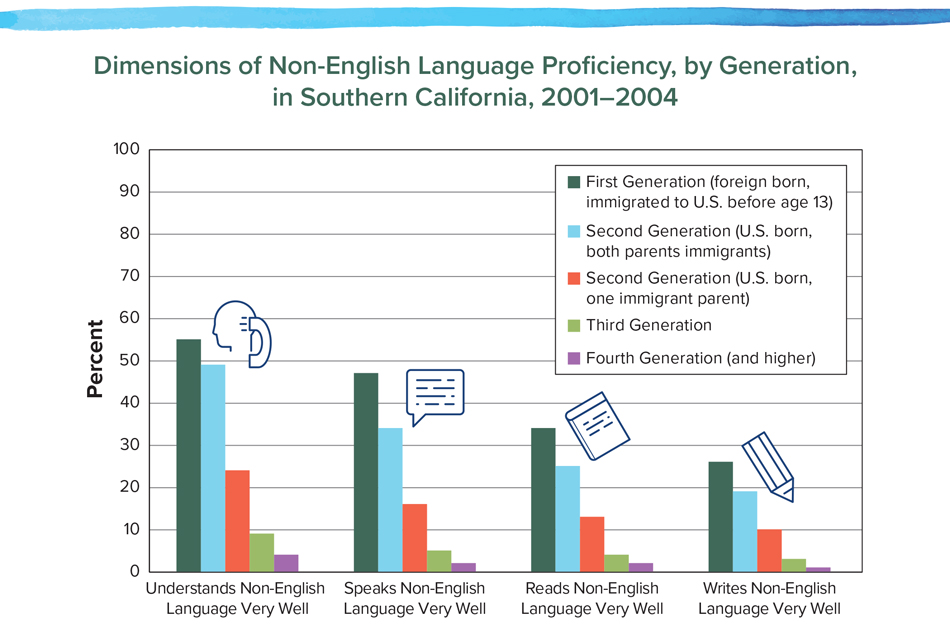

Unfortunately, immigrant communities find it difficult to maintain their proficiency in heritage languages once they enter the United States. A study in Southern California found that language proficiency falls quickly in each generation after the first to enter the country. More than 45 percent of the immigrants in the study who arrived as children under the age of thirteen were able to speak and understand a non-English language well (though they are not necessarily literate in these languages). By the third generation, fewer than one in ten were able to communicate well in their heritage languages.75

By developing strategic frameworks for Native American and heritage language learners and systematic, on-going instruction in heritage languages, schools can play an important role in reversing this trend. They should provide more language opportunities for Native American language learners and heritage speakers in classroom or school settings, allow heritage speakers more chances to exercise their heritage language in non-English language courses like social studies and science, and offer students designated times when they can meet and speak to other students who are heritage speakers. Some districts and states are already piloting such programs. For example, Sealaska Heritage, a nonprofit based in Juneau, Alaska, partners with Juneau schools to teach Southeast Alaskan native languages, like Tlingit, and has established a program to train teachers in local languages.76 The Maine French Heritage Program sponsors after-school language and culture activities in Lewiston and Augusta for students from French-speaking backgrounds in grades one through six.77 And the school district in Beardstown, Illinois, is developing a high school immersion program that is specifically designed to support a student population that is 70 percent heritage Spanish speakers.78

Source: Analysis of data collected by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago in the General Social Survey for the Humanities Indicators.

Similarly, more two- and four-year colleges and universities should make available curricula designed specifically for Native American languages and heritage speakers, and should find ways to offer credit for proficiency in a heritage language. As in K–12 education, some colleges and universities are already experimenting with such curricula. The Spanish Heritage Language Program at the University of Houston offers specific courses for heritage Spanish speakers; students who have successfully completed the intermediate level in this program fulfill the university’s foreign language requirement and are encouraged to enroll in more advanced classes.79 The Universities of Arizona, Washington, and Oregon all support similar programs, providing new contexts for students’ personal and cultural experiences; locating the Spanish spoken at home within a broader Spanish-speaking world; and featuring service-learning opportunities in local Spanish-speaking communities.80 And Columbia University introduced a dedicated track for heritage Russian speakers that brings limited-proficiency students to an advanced level in their heritage language in two semesters, while satisfying the university’s undergraduate second language requirement.81 Each of these programs offers a model that can be adopted elsewhere and applied to other heritage languages.

Source: Alejandro Portes and Rubén G. Rumbaut, Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study (CILS), 1991–2006, ICPSR20520.v2 (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2012), http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR20520.v2; and Rubén G. Rumbaut, Frank D. Bean, Leo R. Chávez, et al., Immigration and Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles (IIMMLA), 2004, ICPSR22627.v1 (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2008), http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR22627.v1. See also Rubén G. Rumbaut, “English Plus: Exploring the Socioeconomic Benefits of Bilingualism in Southern California,” in The Bilingual Advantage: Language, Literacy and the U.S. Labor Market, ed. Rebecca M. Callahan and Patricia C. Gándara (Bristol, United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters, 2014).

Heritage language initiatives at schools and colleges are important, in part, because they recognize forms of self and cultural expression that have been devalued by our educational policies and practices, sometimes to devastating effect. For example, many students who are proficient in English as well as in a heritage language continue to be placed in English development programs based on the false assumption that their knowledge of a second language implies weak English skills, or that further education in a heritage language will hinder students’ mastery of English.82 Occasionally, these decisions can be influenced by financial considerations, since some school districts receive funding when they assign more students to developmental English. In some cases, schools have not been required to inform parents that their children have been placed in such courses. These placements are problematic on several levels: They impede the education of otherwise qualified and capable students. They reinforce the mistaken idea that heritage languages are less valuable than other forms of knowledge. And they threaten the confidence and self-esteem of students who can and should excel within and beyond the classroom.

In place of such reflexive skepticism, individual students and communities would benefit greatly from a new respect for and investment in heritage language learning as an integral component of a broader national language strategy.83 While quality teaching resources already exist for many of the languages taught in U.S. schools, many more will need to be developed to support the great wealth of languages spoken in homes around the United States. The kind of public-private partnerships advocated in the previous section of this report will be crucial in these efforts as lesson plans, textbooks, and other media are developed to facilitate ongoing, lifelong instruction in heritage languages.

Native American Speakers

Currently, the United States is home to over 450,000 speakers of Native American languages. Many of these American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Native American Pacific Islander languages are classified as endangered languages by UNESCO and other organizations supporting cultural preservation. Among languages indigenous to the North American continent (where language loss has been most severe), every Native American language other than Navajo has fewer than twenty thousand speakers and many are down to less than ten speakers. In the Native American Languages Act of 1990, Congress recognized the distinctive political status and cultural importance of all Native American languages and authorized programs to counter a historic “lack of clear, comprehensive, and consistent Federal policy,” which has often “resulted in acts of suppression and extermination of Native American languages and culture.”85

Native North American languages are now the subject of intensive reclamation projects, including the Documenting Endangered Languages joint project of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation. They are taught at tribal colleges and universities as well as at public universities in several states, including Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, Minnesota, and Oklahoma. Alaska and Hawaii have also declared their Native American languages as official state languages.

Over the past twenty years, researchers have discovered that instruction in indigenous languages yields a variety of benefits for Native American children. It has been linked to improvements in:

- Academic achievement, retention rates, and school attendance;

- Local and national achievement test scores;

- Well-being, self-esteem, and self-efficacy; and

- Resiliency to addiction and the prevention of risky behaviors.86

Cosima Lenz

Master of Public Health Candidate at UCLA Fielding School of Public Health

Cosima Lenz is a first-generation American whose family spoke German and English at home. She began learning Spanish as an elementary school student in California and continued to study the language throughout high school, before earning her bachelor’s degree in German with a minor in public health from Northwestern University. Passionate about global health issues and aware of the serious challenges language barriers present to her chosen field, Lenz put her Spanish to use as a volunteer with the Somos Hermanos program—living in full cultural and linguistic immersion in Guatemala while teaching a weekly health class to local women and working at a rural clinic. Now pursuing a master of public health, she recently completed a research internship with the World Health Organization’s Reproductive Health Research Department in Geneva, Switzerland, and has also participated in study abroad and research experiences in Germany and South Africa.

“Having foreign language skills in this day and age is critical due to the increasingly global world in which we live, and it’s why I value my German and Spanish language skills. One of my goals in pursuing a career in public health is to use my Spanish and cross-cultural skills to improve quality and access to health care among the Latino community.”84

ENDNOTES

74. U.S. Census Bureau, “Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over for United States: 2009–2013.”

75. Alejandro Portes and Rubén G. Rumbaut, Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study (CILS), 1991–2006, ICPSR20520.v2 (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2012), http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR20520.v2; and Rubén Rumbaut, Frank D. Bean, Leo R. Chávez, et al., Immigration and Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles (IIMMLA), 2004, ICPSR22627.v1 (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2008), http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR22627.v1. See also Rubén G. Rumbaut, “English Plus: Exploring the Socioeconomic Benefits of Bilingualism in Southern California,” in The Bilingual Advantage: Language, Literacy and the U.S. Labor Market, ed. Callahan and Gándara.

76. Sealaska Heritage, “Education Programs,” http://www.sealaskaheritage.org/institute/education/programs.

77. Maine French Heritage Language Program, “About,” http://www.mfhlp.com/about.html.

78. Center for Applied Linguistics, “Heritage Langue Programs–Spanish: Beardstown CUSD #15 Dual Language Enrichment Program,” http://www.cal.org/heritage/profiles/programs/Spanish_K-12_Beardstown.html.

79. University of Houston, “Heritage Track,” http://www.uh.edu/class/spanish/language-programs/heritage-language/index.php.

80. University of Washington, “Heritage Language Courses,” https://spanport.washington.edu/heritage-language-courses; University of Arizona, “Spanish as a Heritage Language,” http://spanish.arizona.edu/undergrad/spanish-heritage-language; and University of Oregon, “Spanish Heritage Language Program (SHL),” http://rl.uoregon.edu/undergraduate/shl/.

81. Columbia University, “Undergraduate Courses: Russian Language (RUSS),” http://slavic.columbia.edu/search/node/heritage%20Russian.

82. Recent studies suggest that strong skills in a heritage language actually help to promote efficient learning in English. See Karen Thompson, “English Learners’ Time to Reclassification: An Analysis,” Educational Policy (2015).

83. All students, including English speakers, would benefit from a more inclusive and integrative approach to the education of English Language Learners (ELLs). Some schools in Virginia are already experimenting with new “whole school” programs for teaching ELLs, in which every student prepares for mainstream content classes (in science, math, history, and so on) by first participating in in-depth sessions on vocabulary, reading, and writing in English. These programs reduce the time that ELLs spend away from their English-speaking peers and introduce a new educational rigor that has proven helpful to English speakers as well. Early research suggests that this is a path worth pursuing in more districts around the country. Margarita Calderón, “A Whole-School Approach to English Learners,” Educational Leadership 73 (5) (February 2016), http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/feb16/vol73/num05/A_Whole-School_Approach_to_English_Learners.aspx.

84. Email exchanges with the Commission on Language Learning, December 2015 and November 2016.

85. Julie Siebens and Tiffany Julian, “Native North American Languages Spoken at Home in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2006–2010,” American Community Survey Briefs, December 2011, https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/acsbr10-10.pdf; and U.S. Senate, S.2167–Native American Languages Act, October 30, 1990, Public Law No. 101-477, https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/senate-bill/2167/text.

86. Joana Jansen, Lindsay Marean, and Janne Underriner, Benefits of Indigenous Language Learning (Eugene: University of Oregon, 2012), http://pages.uoregon.edu/nwili/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/forwebpageBenefitsL2_ECE10_17_14.pdf; and National Endowment for the Humanities, “Documenting Endangered Languages,” https://www.neh.gov/grants/preservation/documenting-endangered-languages.