Appendix A: Recommendations from Restoring the Foundation

Prescription 1

Secure America’s Leadership in Science and Engineering Research – Especially Basic Research – by Providing Sustainable Federal Funding and Setting Long-Term Investment Goals

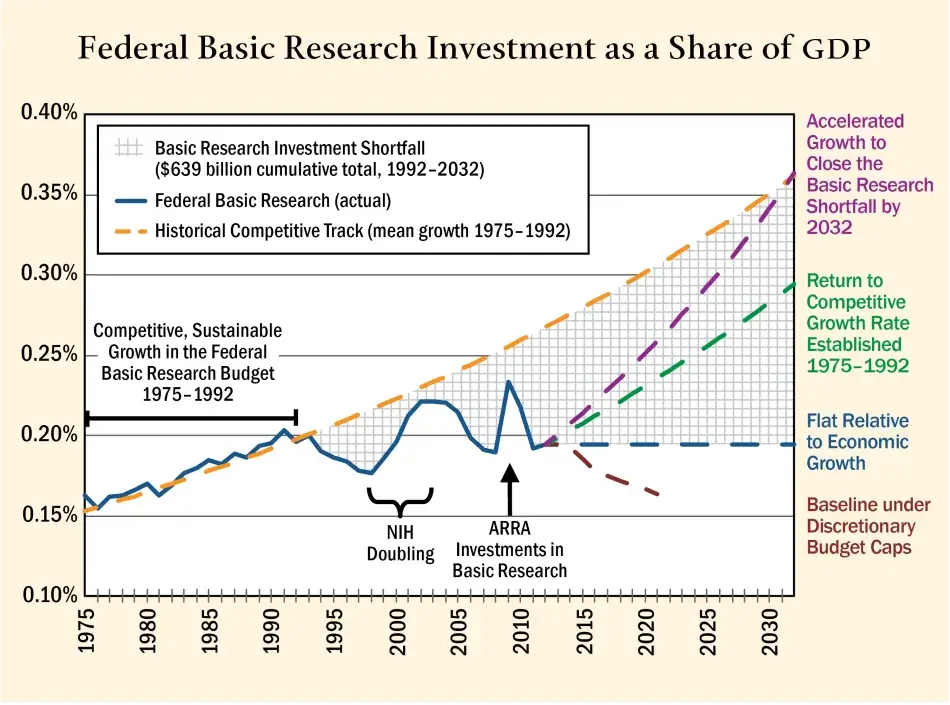

ACTION 1.1 – We recommend that the President and Congress work together to establish a sustainable real growth rate of at least 4 percent in the federal investment in basic research, approximating the average growth rate sustained between 1975 and 1992 (see Figure 13). This growth rate would be compatible with a target of at least 0.3 percent of GDP for federally supported basic research by 2032 (one-tenth the national goal for combined public and private R&D investment adopted by several U.S. presidents). We stress that an increase in support for basic research should not come at the expense of investments in applied research or development, both of which will remain essential for fully realizing the societal benefits of scientific discoveries and new technologies that emerge from basic research.

Should federal obligations for basic research (blue) flatline relative to economic growth, the United States will by 2032 have accumulated a $639 billion shortfall (cross-hatch) in federal support of basic research relative to the 4.4 percent average annual real growth trend (orange) established during the period of 1975 to 1992. This committee recommends that the nation return to this historical competitive growth rate (green), with the ultimate goal of fully closing the basic research shortfall (purple) as the economy improves.

Data Sources: Federal obligations for basic research from 1975 to 2012 are from the National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2014 (Arlington, Va.: National Science Foundation, 2014), Appendix Table 4-34, “Federal Obligations for R&D and R&D Plant, by Character of Work: FYs 1953–2012.” Basic research funding baseline projections are based on the nondefense discretionary funding levels from Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2015 Budget of the U.S. Government (Washington, D.C.: Office of Management and Budget, 2014), Table S-10, “Funding Levels for Appropriated (‘Discretionary’) Programs by Category,” whose baseline levels assume Joint Committee enforcement cap reductions are in effect through 2021. GDP projections assume an average real annual growth rate of 2.2 percent until 2020 and 2.3 percent from 2020 to 2030, according to Jean Chateau, Cuauhtemoc Rebolledo, and Rob Dellink, “An Economic Projection to 2050: The OECD ‘ENV-Linkages’ Model Baseline,” OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 41 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2011), Table 4.

We further recommend that, as the U.S. economy improves, the federal government strive to exceed this growth rate in basic research, with the goal of returning to the sustainable growth path for basic research established between 1975 and 1992.

Productive first steps include:

- Establishment of an aggressive goal of at least 3.3 percent GDP for the total national R&D investment (by all sources) and a national discussion of the means of attaining that goal;

- Strong reauthorization bills, following the model set by the 2007 and 2010 America COMPETES Acts,56 that authorize the investments necessary to renew America’s commitment to science and engineering research and STEM education and reinforce the use of expert peer review in determining the scientific merit of competitive research proposals in all fields;

- Appropriations necessary to realize the promise of strong authorization acts; and

- A “Sense of the Congress” resolution affirming the importance of these goals as a high-priority investment in America’s future.

ACTION 1.2 – We recommend that the President and Congress adopt multiyear appropriations for agencies (or parts of agencies) that primarily support research and graduate STEM education. Providing research agencies with advanced notice of pending budgetary changes would allow them to adjust their grant portfolios and the construction of new facilities accordingly. The resulting efficiency gains would reduce costs while enhancing research productivity.

ACTION 1.3 – We recommend that the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) establish a strategic capital budget process for funding major research instrumentation and facilities, ideally in the context of a broader national capital budget that supports investment in the nation’s infrastructure; and that enabling legislation specifically preclude earmarks or other mechanisms that circumvent merit review.

ACTION 1.4 – We recommend that the President include in the annual budget request to Congress a rolling long-term (five-to-ten-year) plan for the allocation of federal R&D investments – especially funding for major instrumentation that requires many years to plan and build.

Prescription 2

Ensure that the American People Receive the Maximum Benefit from Federal Investments in Research

ACTION 2.1 – We recommend that the President publish a biennial “State of American Science, Engineering & Technology” report giving the administration’s perspective on issues such as those addressed by the Science and Engineering Indicators and related reports published by the National Science Foundation (NSF) National Science Board (NSB),57 and with input from the federal agencies that sit on the President’s National Science and Technology Council (NSTC). The report, if released with the President’s budget, would provide information useful for both the appropriations and authorization legislative processes.

ACTION 2.2 – We recommend the following actions to enhance the productivity of America’s researchers, particularly those based at universities:

ACTION 2.2a – We recommend that the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and Office of Management and Budget lead an effort to streamline or eliminate practices and regulations governing federally funded research that have become burdensome and add to the universities’ administrative overhead while failing to yield appreciable benefits.

ACTION 2.2b – We recommend that universities adopt “best practices” targeted at capital planning, cost-containment efforts, and resource sharing with outside parties, such as those described in the 2012 National Research Council (NRC) report Research Universities and the Future of America.58

ACTION 2.2c – We recommend that universities and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) gradually adopt practices to foster an appropriately sized and sustainable biomedical research workforce.59 Key goals should include reducing the length of graduate school and postdoctoral training and shifting support for education to training grants and fellowships; providing funding for master’s degree programs that may provide more appropriate training for some segments of the biomedical workforce now populated by Ph.D.s; enhancing the role of staff scientists in university laboratories and core facilities; reducing the percentage of faculty salaries supported solely by grants; and securing a renewed commitment from senior scientists to serve on review boards and study sections.

ACTION 2.2d – We recommend that the President and Congress reaffirm the principle that competitive expert peer review is the best way to ensure excellence. Hence, peer review should remain the mechanism by which federal agencies make research award decisions, and review processes and criteria should be left to the discretion of the agencies themselves. In the case of basic research, scientific merit – based on the opinions of experts in the field – should remain the primary consideration for awarding support.

ACTION 2.2e – We recommend that the research funding agencies intensify their efforts to reduce the time that researchers spend writing and reviewing proposals, such as by expanding the use of pre-proposals, providing additional feedback from program officers, allowing authors to respond to reviewers’ comments, further normalizing procedures across the federal government, and experimenting with new approaches to streamline the grant process.

ACTION 2.3 – We recommend that the National Academies, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences convene a series of meetings of nongovernmental organizations and professional societies that focus on science and engineering research, for the purpose of establishing a formal task force, alliance, or new organization to:

- Develop a common message about the nature and importance of science and engineering research that could be disseminated by all interested organizations;

- Elevate science and technology issues in the minds of the American public, business community, and political figures, and restore appropriate public trust;

- Ensure that the recommendations offered by existing science and technology policy organizations, academies, and other advisory bodies remain current and available to institutional leaders and policy-makers in all sectors;

- Cooperate with organizations that are focused on business and commerce, national and domestic security, education and workforce, health and safety, energy and environment, culture and the arts, entertainment, and other societal interests and needs to encourage a discussion of the role of science, engineering, and technology in society; and

- Offer assistance – in real time – to federal and state government, universities, private foundations, and leaders in business and industry to help with implementation of policy reforms.

ACTION 2.4 – In order to have direct access to current information and analysis of important science and technology policy issues, we urge Congress to: 1) significantly expand the science, engineering, and technology assessment capabilities of the Government Accountability Office (GAO), including the size of the technical staff, or alternatively to establish and fund a new organization for that purpose; and 2) explore ways to tap the expertise of American researchers in a timely and non-conflicted manner. In particular, consideration should be given to ways in which either the GAO or another organization with scientific and technical expertise could use crowdsourcing and participatory technology assessment to rapidly collect research, data, and analysis related to specific scientific issues.

Prescription 3

Regain America’s Standing as an Innovation Leader by Establishing a More Robust National Government-University-Industry Research Partnership

ACTION 3.1 – We recommend that the President or Vice President convene a “Summit on the Future of America’s Research Enterprise” with participation from all government, university, and industry sectors and the philanthropic community. The Summit should have the bold action agenda to: assess the current state of science and engineering research in the United States in a global twenty-first-century context; review successful approaches to bringing each sector into closer collaboration; determine where further actions are needed to encourage collaboration; and form a new compact to ensure that the United States remains a leader in science, engineering, technology, and medicine in the coming decades.

ACTION 3.2 – We recommend that the nation’s research universities:

- Experiment with new intellectual property policies and practices that favor the creation of stronger research partnerships with companies over the maximization of revenues;

- Adopt innovative models for technology transfer that can better support the universities’ mission to produce and export new knowledge and educate students;

- Enhance early exposure of graduate students (including doctoral students) to a broad range of non-research career options in business, industry, government, and other sectors, and ensure that they have the necessary skills to be successful;

- Expand professional master’s degree programs in science and engineering, with particular attention to students interested in non-research career options; and

- Increase permeability across sectors through research collaborations and faculty research leaves.

ACTION 3.3 – We recommend that the President and Congress, in consultation with leaders of the nation’s research universities and corporations, consider legislation to remove lingering barriers to university-industry research cooperation, and specifically:

- Help universities overcome impediments to experimenting with new technology transfer policies and procedures that emphasize objectives (such as the creation of new companies and jobs), outcomes, and best practices (such as processes that minimize the time and cost of licensing); and

- Amend the U.S. tax code to encourage closer university-industry cooperation. For example, in the case of industry-funded research conducted in university buildings financed with tax-exempt bonds, the tax code should be amended to allow universities to enter into advance licensing agreements with industry.

ACTION 3.4 – We recommend that the federal agencies that operate or provide major funding for national laboratories60 review their current missions, management, and operations, including the effectiveness of collaborations with universities and industry, and phase in changes as appropriate. While consultation with these laboratories is critical in carrying out such reviews, the burden of reviews and other agency requirements is already heavy and should, over time, be reduced.

ACTION 3.5 – We recommend that corporate boards and chief executives give higher priority to funding research in universities and work with university presidents and boards to develop new forms of partnership: collaborations that can justify increased company investments in university research, especially basic research projects that provide new concepts for translation to application and are best suited for training the next generation of scientists and engineers.

ACTION 3.6 – We strongly urge Congress to make the Research and Experimentation (R&E) Tax Credit permanent, as recommended by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), the National Academies, the Business Roundtable, and many others. Doing so would provide an incentive for industry to invest in long-term research in the United States, including collaborative research with universities such as that recommended under Action 3.5.

ACTION 3.7 – We support the recommendation made by many other organizations, including the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology and the National Academies,61 both to increase the number of H-1B visas and to reshape policies affecting foreign-born researchers in order to attract and retain the best and brightest researchers. Productive steps include allowing foreign students who receive a graduate degree in STEM disciplines from a U.S. university to receive a green card (perhaps contingent on receiving a job offer) and stipulating that each employment-based visa automatically covers a worker’s spouse and children.